Famous Physicist Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unerring in Her Scientific Enquiry and Not Afraid of Hard Work, Marie Curie Set a Shining Example for Generations of Scientists

Historical profile Elements of inspiration Unerring in her scientific enquiry and not afraid of hard work, Marie Curie set a shining example for generations of scientists. Bill Griffiths explores the life of a chemical heroine SCIENCE SOURCE / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY LIBRARY PHOTO SCIENCE / SOURCE SCIENCE 42 | Chemistry World | January 2011 www.chemistryworld.org On 10 December 1911, Marie Curie only elements then known to or ammonia, having a water- In short was awarded the Nobel prize exhibit radioactivity. Her samples insoluble carbonate akin to BaCO3 in chemistry for ‘services to the were placed on a condenser plate It is 100 years since and a chloride slightly less soluble advancement of chemistry by the charged to 100 Volts and attached Marie Curie became the than BaCl2 which acted as a carrier discovery of the elements radium to one of Pierre’s electrometers, and first person ever to win for it. This they named radium, and polonium’. She was the first thereby she measured quantitatively two Nobel prizes publishing their results on Boxing female recipient of any Nobel prize their radioactivity. She found the Marie and her husband day 1898;2 French spectroscopist and the first person ever to be minerals pitchblende (UO2) and Pierre pioneered the Eugène-Anatole Demarçay found awarded two (she, Pierre Curie and chalcolite (Cu(UO2)2(PO4)2.12H2O) study of radiactivity a new atomic spectral line from Henri Becquerel had shared the to be more radioactive than pure and discovered two new the element, helping to confirm 1903 physics prize for their work on uranium, so reasoned that they must elements, radium and its status. -

3.Joule's Experiments

The Force of Gravity Creates Energy: The “Work” of James Prescott Joule http://www.bookrags.com/biography/james-prescott-joule-wsd/ James Prescott Joule (1818-1889) was the son of a successful British brewer. He tinkered with the tools of his father’s trade (particularly thermometers), and despite never earning an undergraduate degree, he was able to answer two rather simple questions: 1. Why is the temperature of the water at the bottom of a waterfall higher than the temperature at the top? 2. Why does an electrical current flowing through a conductor raise the temperature of water? In order to adequately investigate these questions on our own, we need to first define “temperature” and “energy.” Second, we should determine how the measurement of temperature can relate to “heat” (as energy). Third, we need to find relationships that might exist between temperature and “mechanical” energy and also between temperature and “electrical” energy. Definitions: Before continuing, please write down what you know about temperature and energy below. If you require more space, use the back. Temperature: Energy: We have used the concept of gravity to show how acceleration of freely falling objects is related mathematically to distance, time, and speed. We have also used the relationship between net force applied through a distance to define “work” in the Harvard Step Test. Now, through the work of Joule, we can equate the concepts of “work” and “energy”: Energy is the capacity of a physical system to do work. Potential energy is “stored” energy, kinetic energy is “moving” energy. One type of potential energy is that induced by the gravitational force between two objects held at a distance (there are other types of potential energy, including electrical, magnetic, chemical, nuclear, etc). -

Wolfgang Pauli Niels Bohr Paul Dirac Max Planck Richard Feynman

Wolfgang Pauli Niels Bohr Paul Dirac Max Planck Richard Feynman Louis de Broglie Norman Ramsey Willis Lamb Otto Stern Werner Heisenberg Walther Gerlach Ernest Rutherford Satyendranath Bose Max Born Erwin Schrödinger Eugene Wigner Arnold Sommerfeld Julian Schwinger David Bohm Enrico Fermi Albert Einstein Where discovery meets practice Center for Integrated Quantum Science and Technology IQ ST in Baden-Württemberg . Introduction “But I do not wish to be forced into abandoning strict These two quotes by Albert Einstein not only express his well more securely, develop new types of computer or construct highly causality without having defended it quite differently known aversion to quantum theory, they also come from two quite accurate measuring equipment. than I have so far. The idea that an electron exposed to a different periods of his life. The first is from a letter dated 19 April Thus quantum theory extends beyond the field of physics into other 1924 to Max Born regarding the latter’s statistical interpretation of areas, e.g. mathematics, engineering, chemistry, and even biology. beam freely chooses the moment and direction in which quantum mechanics. The second is from Einstein’s last lecture as Let us look at a few examples which illustrate this. The field of crypt it wants to move is unbearable to me. If that is the case, part of a series of classes by the American physicist John Archibald ography uses number theory, which constitutes a subdiscipline of then I would rather be a cobbler or a casino employee Wheeler in 1954 at Princeton. pure mathematics. Producing a quantum computer with new types than a physicist.” The realization that, in the quantum world, objects only exist when of gates on the basis of the superposition principle from quantum they are measured – and this is what is behind the moon/mouse mechanics requires the involvement of engineering. -

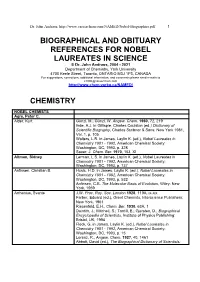

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

Weberˇs Planetary Model of the Atom

Weber’s Planetary Model of the Atom Bearbeitet von Andre Koch Torres Assis, Gudrun Wolfschmidt, Karl Heinrich Wiederkehr 1. Auflage 2011. Taschenbuch. 184 S. Paperback ISBN 978 3 8424 0241 6 Format (B x L): 17 x 22 cm Weitere Fachgebiete > Physik, Astronomie > Physik Allgemein schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Weber’s Planetary Model of the Atom Figure 0.1: Wilhelm Eduard Weber (1804–1891) Foto: Gudrun Wolfschmidt in der Sternwarte in Göttingen 2 Nuncius Hamburgensis Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften Band 19 Andre Koch Torres Assis, Karl Heinrich Wiederkehr and Gudrun Wolfschmidt Weber’s Planetary Model of the Atom Ed. by Gudrun Wolfschmidt Hamburg: tredition science 2011 Nuncius Hamburgensis Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften Hg. von Gudrun Wolfschmidt, Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Mathematik und Technik, Universität Hamburg – ISSN 1610-6164 Diese Reihe „Nuncius Hamburgensis“ wird gefördert von der Hans Schimank-Gedächtnisstiftung. Dieser Titel wurde inspiriert von „Sidereus Nuncius“ und von „Wandsbeker Bote“. Andre Koch Torres Assis, Karl Heinrich Wiederkehr and Gudrun Wolfschmidt: Weber’s Planetary Model of the Atom. Ed. by Gudrun Wolfschmidt. Nuncius Hamburgensis – Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Band 19. Hamburg: tredition science 2011. Abbildung auf dem Cover vorne und Titelblatt: Wilhelm Weber (Kohlrausch, F. (Oswalds Klassiker Nr. 142) 1904, Frontispiz) Frontispiz: Wilhelm Weber (1804–1891) (Feyerabend 1933, nach S. -

The Concept of Field in the History of Electromagnetism

The concept of field in the history of electromagnetism Giovanni Miano Department of Electrical Engineering University of Naples Federico II ET2011-XXVII Riunione Annuale dei Ricercatori di Elettrotecnica Bologna 16-17 giugno 2011 Celebration of the 150th Birthday of Maxwell’s Equations 150 years ago (on March 1861) a young Maxwell (30 years old) published the first part of the paper On physical lines of force in which he wrote down the equations that, by bringing together the physics of electricity and magnetism, laid the foundations for electromagnetism and modern physics. Statue of Maxwell with its dog Toby. Plaque on E-side of the statue. Edinburgh, George Street. Talk Outline ! A brief survey of the birth of the electromagnetism: a long and intriguing story ! A rapid comparison of Weber’s electrodynamics and Maxwell’s theory: “direct action at distance” and “field theory” General References E. T. Wittaker, Theories of Aether and Electricity, Longam, Green and Co., London, 1910. O. Darrigol, Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einste in, Oxford University Press, 2000. O. M. Bucci, The Genesis of Maxwell’s Equations, in “History of Wireless”, T. K. Sarkar et al. Eds., Wiley-Interscience, 2006. Magnetism and Electricity In 1600 Gilbert published the “De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure” (On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on That Great Magnet the Earth). ! The Earth is magnetic ()*+(,-.*, Magnesia ad Sipylum) and this is why a compass points north. ! In a quite large class of bodies (glass, sulphur, …) the friction induces the same effect observed in the amber (!"#$%&'(, Elektron). Gilbert gave to it the name “electricus”. -

Richard P. Feynman Author

Title: The Making of a Genius: Richard P. Feynman Author: Christian Forstner Ernst-Haeckel-Haus Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena Berggasse 7 D-07743 Jena Germany Fax: +49 3641 949 502 Email: [email protected] Abstract: In 1965 the Nobel Foundation honored Sin-Itiro Tomonaga, Julian Schwinger, and Richard Feynman for their fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics and the consequences for the physics of elementary particles. In contrast to both of his colleagues only Richard Feynman appeared as a genius before the public. In his autobiographies he managed to connect his behavior, which contradicted several social and scientific norms, with the American myth of the “practical man”. This connection led to the image of a common American with extraordinary scientific abilities and contributed extensively to enhance the image of Feynman as genius in the public opinion. Is this image resulting from Feynman’s autobiographies in accordance with historical facts? This question is the starting point for a deeper historical analysis that tries to put Feynman and his actions back into historical context. The image of a “genius” appears then as a construct resulting from the public reception of brilliant scientific research. Introduction Richard Feynman is “half genius and half buffoon”, his colleague Freeman Dyson wrote in a letter to his parents in 1947 shortly after having met Feynman for the first time.1 It was precisely this combination of outstanding scientist of great talent and seeming clown that was conducive to allowing Feynman to appear as a genius amongst the American public. Between Feynman’s image as a genius, which was created significantly through the representation of Feynman in his autobiographical writings, and the historical perspective on his earlier career as a young aspiring physicist, a discrepancy exists that has not been observed in prior biographical literature. -

08. Ampère and Faraday Darrigol (2000), Chap 1

08. Ampère and Faraday Darrigol (2000), Chap 1. A. Pre-1820. (1) Electrostatics (frictional electricity) • 1780s. Coulomb's description: ! Two electric fluids: positive and negative. ! Inverse square law: It follows therefore from these three tests, that the repulsive force that the two balls -- [which were] electrified with the same kind of electricity -- exert on each other, Charles-Augustin de Coulomb follows the inverse proportion of (1736-1806) the square of the distance."" (2) Magnetism: Coulomb's description: • Two fluids ("astral" and "boreal") obeying inverse square law. • No magnetic monopoles: fluids are imprisoned in molecules of magnetic bodies. (3) Galvanism • 1770s. Galvani's frog legs. "Animal electricity": phenomenon belongs to biology. • 1800. Volta's ("volatic") pile. Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) • Pile consists of alternating copper and • Charged rod connected zinc plates separated by to inner foil. brine-soaked cloth. • Outer foil grounded. • A "battery" of Leyden • Inner and outer jars that can surfaces store equal spontaeously recharge but opposite charges. themselves. 1745 Leyden jar. • Volta: Pile is an electric phenomenon and belongs to physics. • But: Nicholson and Carlisle use voltaic current to decompose Alessandro Volta water into hydrogen and oxygen. Pile belongs to chemistry! (1745-1827) • Are electricity and magnetism different phenomena? ! Electricity involves violent actions and effects: sparks, thunder, etc. ! Magnetism is more quiet... Hans Christian • 1820. Oersted's Experimenta circa effectum conflictus elecrici in Oersted (1777-1851) acum magneticam ("Experiments on the effect of an electric conflict on the magnetic needle"). ! Galvanic current = an "electric conflict" between decompositions and recompositions of positive and negative electricities. ! Experiments with a galvanic source, connecting wire, and rotating magnetic needle: Needle moves in presence of pile! "Otherwise one could not understand how Oersted's Claims the same portion of the wire drives the • Electric conflict acts on magnetic poles. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

More Eugene Wigner Stories; Response to a Feynman Claim (As Published in the Oak Ridger’S Historically Speaking Column on August 29, 2016)

More Eugene Wigner stories; Response to a Feynman claim (As published in The Oak Ridger’s Historically Speaking column on August 29, 2016) Carolyn Krause has collected a couple more stories about Eugene Wigner, plus a response by Y- 12 to allegations by Richard Feynman in a book that included a story on his experience at Y-12 during World War II. … Mary Ann Davidson, widow of Jack Davidson, a longtime member of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Instrumentation and Controls Division, told me about Jack’s encounter with Wigner one day. Once Eugene Wigner had trouble opening his briefcase while visiting ORNL. He was referred to Jack Davidson in the old Instrumentation and Controls Division. Jack managed to open it for him. As was his custom, Wigner asked Jack about his research. Jack, who later won an R&D-100 award, said he was building a camera that will imitate a fly’s eye; in other words, it will capture light coming from a variety of directions. The topic of television and TV cameras came up. Wigner said he wondered how TV works. So Davidson explained the concept to him. Charles Jones told me this story about Eugene Wigner when he visited ORNL in the 1980s. Jones, who was technical director of the Holifield Heavy Ion Research Facility, said he invited Wigner to accompany him to the top of the HHIRF tower, and Wigner happily accepted the offer. At the top Wigner looked down at all the ORNL buildings, most of which had been constructed after he was the lab’s research director in 1946-47. -

ARIE SKLODOWSKA CURIE Opened up the Science of Radioactivity

ARIE SKLODOWSKA CURIE opened up the science of radioactivity. She is best known as the discoverer of the radioactive elements polonium and radium and as the first person to win two Nobel prizes. For scientists and the public, her radium was a key to a basic change in our understanding of matter and energy. Her work not only influenced the development of fundamental science but also ushered in a new era in medical research and treatment. This file contains most of the text of the Web exhibit “Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity” at http://www.aip.org/history/curie/contents.htm. You must visit the Web exhibit to explore hyperlinks within the exhibit and to other exhibits. Material in this document is copyright © American Institute of Physics and Naomi Pasachoff and is based on the book Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity by Naomi Pasachoff, Oxford University Press, copyright © 1996 by Naomi Pasachoff. Site created 2000, revised May 2005 http://www.aip.org/history/curie/contents.htm Page 1 of 79 Table of Contents Polish Girlhood (1867-1891) 3 Nation and Family 3 The Floating University 6 The Governess 6 The Periodic Table of Elements 10 Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev (1834-1907) 10 Elements and Their Properties 10 Classifying the Elements 12 A Student in Paris (1891-1897) 13 Years of Study 13 Love and Marriage 15 Working Wife and Mother 18 Work and Family 20 Pierre Curie (1859-1906) 21 Radioactivity: The Unstable Nucleus and its Uses 23 Uses of Radioactivity 25 Radium and Radioactivity 26 On a New, Strongly Radio-active Substance -

Atomic Theories and Models

Atomic Theories and Models Answer these questions on your own. Early Ideas About Atoms: Go to http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0905226.html and read the section on “Greek Origins” in order to answer the following: 1. What were Leucippus and Democritus ideas regarding matter? 2. Describe what these philosophers thought the atom looked like? 3. How were the ideas of these two men received by Aristotle, and what was the result on the progress of atomic theory for the next couple thousand years? Alchemists: Go to http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/alchemy and/or http://www.scienceandyou.org/articles/ess_08.shtml to answer the following: 4. What was the ultimate goal of an alchemist? 5. What is the word used to describe changing something of little value into something of higher value? 6. Did any alchemist achieve this goal? John Dalton’s Atomic Theory: Go to http://www.rsc.org/chemsoc/timeline/pages/1803.html and answer the following: 7. When did Dalton form his atomic theory. 8. List the six ideas of Dalton’s theory: a. b. c. d. e. f. Mendeleev: Go to http://www.chemistry.co.nz/mendeleev.htm and/or http://www.aip.org/history/curie/periodic.htm to answer the following: 9. What was Mendeleev’s famous contribution to chemistry? 10. How did Mendeleev arrange his periodic table? 11. Why did Mendeleev leave blank spaces in his periodic table? J. J. Thomson: Go to http://www.universetoday.com/38326/plum-pudding-model/ and http://www.chemheritage.org/discover/online-resources/chemistry-in-history/themes/atomic-and- nuclear-structure/thomson.aspx and http://www.chem.uiuc.edu/clcwebsite/cathode.html and http://www-outreach.phy.cam.ac.uk/camphy/electron/electron_index.htm and http://www.iun.edu/~cpanhd/C101webnotes/modern-atomic-theory/rutherford-model.html to answer the following: 12.