SPRING 1968 3 Rabinal Achí

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

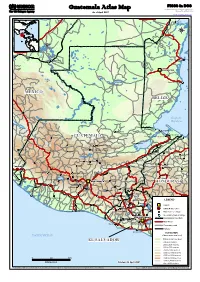

Guatemala Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 Email : [email protected]

FICSS in DOS Guatemala Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 Email : [email protected] ((( Corozal Guatemala_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Balancan !! !! !! !! Tenosique Belize City !! BELMOPANBELMOPAN Stann Creek Town !! MEXICOMEXICO BELIZEBELIZE !! Golfo de Honduras San Juan ((( !! Lívingston !! El Achiotal !! Puerto Barrios GUATEMALAGUATEMALA Puerto Santo Tomás de Castilla ((( ((( ((( Soloma ((( Cuyamel Cobán ((( El Estor ((( ((( Chajul ((( !! ((( San Pedro Carchá ((( Morales !! Motozintla Huehuetenango !! San Cristóbal Verapaz ((( Cunen ((( ((( !! Macuelizo ((( ((( Los Amates((( Petoa ((( Cubulco Salamá Trinidad ((( ((( !! Gualán ((( !! !! ((( !! ((( San Sebastián ((( San Jerónimo ((( Jesus Maria La Agua ((( !! Rabinal ((( Protección ((( Joyabaj TapachulaTapachula Totonicapán ((( Zacapa !! Naranjito ((( ((( !! Tapachula ((( ((( Santa Bárbara ((( Quezaltenango !! Dulce Nombre ((( !! San José Poaquil !! Chiquimula !! !! Sololá !! Santa Rosa !! Comalapa ((( Patzún !! Santiago Atitlán !! Tecun Uman !! Chimaltenango GUATEMALAGUATEMALA !! Jalapa HONDURASHONDURAS Mazatenango HONDURASHONDURAS Antigua ((( !! Esquipulas !! !! Retalhuleu ((( !! ((( Ciudad Vieja ((( Monjas Alotenango ((( Nueva Ocotepeque !! ((( Santa Catarina Mita Amatitlán ((( ((( Patulul ((( Ayarza Río Bravo ((( ((( Metapán !! !! Escuintla ((( !! ((( !! Jutiapa((( ((( !! Champerico ((( !! Cuilapa !! Asunción Mita ((( Yamarang Pueblo Nuevo Tiquisate ((( Erandique Yupiltepeque ((( ((( Atescatempa Nueva Concepción LEGEND -

Cooperative Agreement on Human Settlements and Natural Resource Systems Analysis

COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT ON HUMAN SETTLEMENTS AND NATURAL RESOURCE SYSTEMS ANALYSIS CENTRAL PLACE SYSTEMS IN GUATEMALA: THE FINDINGS OF THE INSTITUTO DE FOMENTO MUNICIPAL (A PRECIS AND TRANSLATION) RICHARD W. WILKIE ARMIN K. LUDWIG University of Massachusetts-Amherst Rural Marketing Centers Working Gro'p Clark University/Institute for Development Anthropology Cooperative Agreemeat (USAID) Clark University Institute for Development Anthropology International Development Program Suite 302, P.O. Box 818 950 Main Street 99 Collier Street Worcester, MA 01610 Binghamton, NY 13902 CENTRAL PLACE SYSTEMS IN GUATEMALA: THE FINDINGS OF THE INSTITUTO DE FOMENTO MUNICIPAL (A PRECIS AND TRANSLATION) RICHARD W. WILKIE ARMIN K. LUDWIG Univer ity of Massachusetts-Amherst Rural Marketing Centers Working Group Clark University/Institute for Development Anthropology Cooperative Agreement (USAID) August 1983 THE ORGANIZATION OF SPACE IN THE CENTRAL BELT OF GUATEMALA (ORGANIZACION DEL ESPACIO EN LA FRANJA CENTRAL DE LA REPUBLICA DE GUATEMALA) Juan Francisco Leal R., Coordinator of the Study Secretaria General del Consejo Nacional de Planificacion Economica (SGCNPE) and Agencia Para el Desarrollo Internacional (AID) Instituto de Fomento Municipal (INFOM) Programa: Estudios Integrados de las Areas Rurales (EIAR) Guatemala, Octubre 1981 Introduction In 1981 the Guatemalan Institute for Municipal Development (Instituto de Fomento Municipal-INFOM) under its program of Integrated Studies of Rural Areas (Est6dios Integrados de las Areas Rurales-EIAR) completed the work entitled Organizacion del Espcio en la Franja Centrol de la Republica de Guatemala (The Organization of Space in the Central Belt of Guatemala). This work had its origins in an agreement between the government of Guatemala, represented by the General Secretariat of the National Council for Economic Planning, and the government of the United States through its Agency for International Development. -

BAJA VERAPAZ CHIMALTENANGO CHIQUIMULA Direcciones De Las

Direcciones de las Oficinas del Registro Nacional de las Personas Abril 15́ No. DEPARTAMENTO MUNICIPIO REGISTRO AUXILIAR DIRECCION SEDE ALTA VERAPAZ 1 ALTA VERAPAZ COBAN 4a. avenida 4-50, Barrio Santo Domingo, zona 3 2 ALTA VERAPAZ SANTA CRUZ VERAPAZ Calle 3 de Mayo, Zona 4 3 ALTA VERAPAZ SAN CRISTOBAL VERAPAZ 3a. Avenida 1-38 Zona 1, Barrio Santa Ana 4 ALTA VERAPAZ TACTIC 8 Avenida 4-72 Zona 1, Barrio La Asunción 5 ALTA VERAPAZ TAMAHU Barrio San Pablo, Tamahu 6 ALTA VERAPAZ TUCURU Barrio El Centro, Calle Principal, Avenida Tucurú 7 ALTA VERAPAZ PANZOS Barrio el Centro, Calle del Estadio a 150 Mts. De la Municipalidad 8 ALTA VERAPAZ SENAHU Calle Principal del Municipio de Senahú 9 ALTA VERAPAZ SAN PEDRO CARCHA 2a. Calle 12-58 zona 5, Barrio Chibujbu 10 ALTA VERAPAZ SAN JUAN CHAMELCO 2a. Ave. Barrio san Juan 11 ALTA VERAPAZ LANQUIN Cruce el Pajal Sebol Lanquin 12 ALTA VERAPAZ SANTA MARIA CAHABON Barrio Santiago 89-97 zona 0, camino a Escuela Saquija 13 ALTA VERAPAZ CHISEC Barrio el Centro, Lote 241-1 14 ALTA VERAPAZ CHAHAL Barrio el Centro, a un costado del TSE 15 ALTA VERAPAZ FRAY BARTOLOME DE LAS CASAS F.T.N. 0-70 zona 1 16 ALTA VERAPAZ SANTA CATALINA LA TINTA Barrio Centro Zona 4 17 ALTA VERAPAZ RAXRUHA barrio concepcion lote 47, centro urbano poligono 1, camino a la Aldea la Isla BAJA VERAPAZ 1 BAJA VERAPAZ SALAMA 6a Avenida 5-71 Zona 1, salama 2 BAJA VERAPAZ SAN MIGUEL CHICAJ Cantón La Cruz 3 BAJA VERAPAZ RABINAL 3a. -

Experiencias En El Programa De SAN En Comunidades Rurales De Rabinal

UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA FACULTAD DE AGRONOMIA INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES AGRONOMICAS Y AMBIENTALES “EXPERIENCIAS EN EL PROGRAMA DE SEGURIDAD ALIMENTARIA Y NUTRICIONAL EN COMUNIDADES RURALES DE RABINAL Y CUBULCO, DEPARTAMENTO DE BAJA VERAPAZ” GUATEMALA, SEPTIEMBRE 2009. UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA FACULTAD DE AGRONOMIA INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES AGRONOMICAS Y AMBIENTALES EXPERIENCIAS EN EL PROGRAMA DE SEGURIDAD ALIMENTARIA Y NUTRICIONAL EN COMUNIDADES RURALES DE RABINAL Y CUBULCO, DEPARTAMENTO DE BAJA VERAPAZ TESIS PRESENTADA A LA HONORABLE JUNTA DIRECTIVA DE LA FACULTAD DE AGRONOMIA DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA POR MARIO BERNABE AREVALO JUCUB En el acto de investidura como INGENIERO AGRÓNOMO en SISTEMAS DE PRODUCCIÓN AGRÍCOLA EN EL GRADO ACADEMICO DE LICENCIADO Guatemala, Septiembre 2009. UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA FACULTAD DE AGRONOMIA INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES AGRONOMICAS Y AMBIENTALES RECTOR Lic. Carlos Estuardo Gálvez Barrios JUNTA DIRECTIVA DE LA FACULTAD DE AGRONOMIA Decano MSc. Francisco Javier Vásquez Vásquez Vocal I Ing. Agr. Waldemar Nufio Reyes Vocal II Ing. Agr. Walter Arnoldo Reyes Sanabria Vocal III MSc. Danilo Ernesto Dardón Ávila Vocal IV P. For. Axel Esaú Cuma Vocal V Br. Carlos Alberto Monterroso Gonzales Secretario MSc. Edwin Enrique Cano Morales Guatemala, Septiembre 2009 Guatemala, Septiembre 2009. Honorable Junta Directiva. Honorable Tribunal Examinador. Facultad de Agronomía. Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Presente. Distinguidos miembros: De conformidad con las normas establecidas en la Ley Orgánica de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, tengo el honor de someter a su consideración el trabajo de tesis del Programa Extraordinario, titulado: “EXPERIENCIAS EN EL PROGRAMA DE SEGURIDAD ALIMENTARIA Y NUTRICIONAL EN COMUNIDADES RURALES DE RABINAL Y CUBULCO, DEPARTAMENTO DE BAJA VERAPAZ” Presentado como requisito previo para optar al Titulo de Ingeniero Agrónomo en Sistemas de Producción Agrícola, en el grado académico de Licenciado. -

Zona Paz Economic Corridor Strategy

Zona Paz Economic Corridor Strategy Concept Paper Guatemala-CAP Income Generation Cambridge, MA Activities Project Lexington, MA Hadley, MA (AGIL) Bethesda, MD Washington, DC Chicago, IL Implemented by: Cairo, Egypt Abt Associates Inc. Johannesburg, South Africa #520-C-00-00-00035-00 May 2000 Prepared for United States Agency for Abt Associates Inc. International Development/ Suite 600 Guatemala 4800 Montgomery Lane 1A Calle 7-66, Zona 9 Bethesda, MD 20814-5341 Guatemala City, Guatemala Prepared by Wingerts Consulting, Stephen Wingert ZONAPAZ Economic Corridor Strategy Concept Paper for USAID/Guatemala Sustainable Increases in Household Income and Food Security for Rural Poor in Selected Geographic Areas, SO4, IRs 1 and 2 Prepared by Stephen Wingert, Wingerts Consulting, under Contract No. 520-C-00-00-00035-00 with USAID/Guatemala (under Subcontract with Abt Associates Inc.) May 2000 Table of Contents Table of Contents............................................................................................................. i Acronyms .........................................................................................................................ii I. Background.............................................................................................................. 1 II. Past experience with spatial development models................................................... 2 III. USAID program activities that could contribute to an economic corridor strategy.... 4 IV. Potential economic corridors in USAID’s six priority departments........................... -

Plan De Sánchez Massacre V

Inter-American Court of Human Rights Case of Plan de Sánchez Massacre v. Guatemala Judgment of April 29, 2004 (Merits) In the case of Plan de Sánchez Massacre, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, composed of the following judges: Sergio García Ramírez, President; Alirio Abreu Burelli, Vice-President; Oliver Jackman, Judge; Antônio A. Cançado Trindade, Judge; Cecilia Medina Quiroga, Judge; Manuel E. Ventura Robles, Judge; Diego García-Sayán, Judge; and Alejandro Sánchez Garrido, Judge ad hoc ; also present, Pablo Saavedra Alessandri, Secretary; pursuant to Articles 29, 53, 56, 57 and 58 of the Rules of Procedure of the Court (hereinafter “the Rules of Procedure”), issues the following Judgment. I INTRODUCTION OF THE CASE 1. On July 31, 2002 the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (hereinafter “the Commission” or “the Inter-American Commission”) filed an application before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (hereinafter “the Court” or “the Inter-American Court”) against the State of Guatemala (hereinafter “the State” or “Guatemala”), originating in petition No. 11,763, received by the Secretariat of the Commission on October 25, 1996. 2. The Commission filed the application based on Article 51 of the American Convention on Human Rights (hereinafter “the American Convention” or “the Convention”), with the aim that the Court “find the State of Guatemala internationally responsible for violations of the rights to humane treatment, to judicial protection, to fair trial, to equal treatment, to freedom of conscience and of religion, -

Mapas De Pobreza Y Desigualdad De Guatemala

Mapas de pobreza y desigualdad de Guatemala Insumo preliminar elaborado por ASIES Sujeto a edición final No es un documento oficial Guatemala, abril de 2005 INDICE 1. INTRODUCCION...............................................................................................................5 2. ASPECTOS CONCEPTUALES GENERALES.................................................................6 A. LA POBREZA Y LAS PRINCIPALES FORMAS DE MEDIRLA .......................................................6 i. Las medidas de bienestar..................................................................................................6 ii. El umbral o las líneas de pobreza..................................................................................8 iii. Los indicadores de pobreza...........................................................................................8 B. FUENTES DE INFORMACIÓN PARA EL ESTUDIO DE LA POBREZA............................................8 C. ¿QUÉ ES UN MAPA DE POBREZA?.........................................................................................9 D. EL USO DE LOS MAPAS DE POBREZA .................................................................................10 3. MAPA DE POBREZA 2002...............................................................................................12 A. ASPECTOS METODOLÓGICOS.............................................................................................12 i. Medidas de bienestar y líneas de pobreza .......................................................................12 -

Instituto Nacional De Bosques DIRECTORIO

Instituto Nacional De Bosques DIRECTORIO: REGIONES Y SUB-REGIONES Actualizado al mes de Octubre 2014 REGI DEPARTAMEN TELÉFON DIRECCIÓN FÍSICA CORREO RESPONSABLE ON TO OS ELECTRÓNICO Edgar Romeo Rodríguez 7av 6-80 zona 13 ( A un I Metropolitana 23214500 [email protected] Sandoval costado del Adolfo Hall) Interior parque nacional las victorias entrada por el estadio Héctor David Madrid II Cobán 7951-3051 Verapaz zona 1 Coban [email protected] Montenegro A.V ( antiguas instalaciones de EDECRI) 10 av 4-21 zona 6 II-1 Tactic Hugo Leonel Floresv 7952 9234 entrada a col. El conde [email protected] Tac Tic , Alta Verapaz Marbin Anibal Caballeros 2 calle 4-91 zona 1 II-2 Rabinal 7938-8327 [email protected] Herrera rabinal, Baja Verapaz Interior parque nacional las victorias entrada por el estadio II-3 Cobán Edgar René Alva Macz 4027-6371 Verapaz zona 1 Coban [email protected] A.V ( antiguas instalaciones de EDECRI) Barrio Abajo , contiguo Sergio Eliseo Jimenez [email protected] II-4 San Jerónimo 7940-2928 aaursa, San Jeronimo Pineda .gt Baja Verapaz Lote 96 centro urbano Fray Bartolomé Carlos Francisco Valdizón 1 municipio fray [email protected] II-5 5558-3460 de las Casas Soto bartolome de las casas ob.gt Alta Verapaz 3 calle 2 avenida lote Ixcán, Playa Fredy Amilcar Bolaños 98 apartamento #3 II-6 7755-7810 [email protected] Grande Cano Edificio los Claveles zona 1 Ixcan, Quiché Sede en la Eco región Rony Enrique Vaides Administracion Parque II-7 40326197 [email protected] LachuaSalacuim Medina Nacional Laguna Lachua Alta Verapaz -

Estimaciones De La Población Total Por Municipio. Período 2008-2020

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA Guatemala: Estimaciones de la Población total por municipio. Período 2008-2020. (al 30 de junio) PERIODO Departamento y Municipio 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 REPUBLICA 13,677,815 14,017,057 14,361,666 14,713,763 15,073,375 15,438,384 15,806,675 16,176,133 16,548,168 16,924,190 17,302,084 17,679,735 18,055,025 Guatemala 2,994,047 3,049,601 3,103,685 3,156,284 3,207,587 3,257,616 3,306,397 3,353,951 3,400,264 3,445,320 3,489,142 3,531,754 3,573,179 Guatemala 980,160 984,655 988,150 990,750 992,541 993,552 993,815 994,078 994,341 994,604 994,867 995,130 995,393 Santa Catarina Pinula 80,781 82,976 85,290 87,589 89,876 92,150 94,410 96,656 98,885 101,096 103,288 105,459 107,610 San José Pinula 63,448 65,531 67,730 69,939 72,161 74,395 76,640 78,896 81,161 83,433 85,712 87,997 90,287 San José del Golfo 5,596 5,656 5,721 5,781 5,837 5,889 5,937 5,981 6,021 6,057 6,090 6,118 6,143 Palencia 55,858 56,922 58,046 59,139 60,202 61,237 62,242 63,218 64,164 65,079 65,963 66,817 67,639 Chinuautla 115,843 118,502 121,306 124,064 126,780 129,454 132,084 134,670 137,210 139,701 142,143 144,535 146,876 San Pedro Ayampuc 62,963 65,279 67,728 70,205 72,713 75,251 77,819 80,416 83,041 85,693 88,371 91,074 93,801 Mixco 462,753 469,224 474,421 479,238 483,705 487,830 491,619 495,079 498,211 501,017 503,504 505,679 507,549 San Pedro Sacatepéquez 38,261 39,136 40,059 40,967 41,860 42,740 43,605 44,455 45,291 46,109 46,912 47,698 48,467 San Juan Sacatepéquez 196,422 202,074 208,035 213,975 219,905 -

FP145: RELIVE – Resilient Livelihoods of Vulnerable Smallholder Farmers in the Mayan Landscapes and the Dry Corridor of Guatemala

FP145: RELIVE – REsilient LIVElihoods of vulnerable smallholder farmers in the Mayan landscapes and the Dry Corridor of Guatemala Guatemala | FAO | B.27/02 19 November 2020 FUNDING PROPOSAL TO THE GREEN CLIMATE FUND – RELIVE – REsilient LIVElihoods of vulnerable smallholder farmers in the Mayan landscapes and the Dry Corridor of Guatemala ANNEX 8 GENDER ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION FP V09 APR26 Republic of Guatemala April 2020 Table of Contents 1. Acronyms ................................................................................................................ 4 Part I: Gender Analysis and Evaluation ...................................................................... 5 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 3. General information at country level .................................................................... 6 3.1 The state of affairs of rural women in Guatemala ......................................................... 6 3.2 Demographic data........................................................................................................ 6 3.3 Rurality and rural women ............................................................................................. 6 3.4 The context of the project’s intervention areas ............................................................. 7 3.4.1 Alta Verapaz Department ..................................................................................................... 7 3.4.2 Baja Verapaz Department -

CATALOG of HISTORIC SEISMICITY in the VICINITY of the F CHIXOY-POLOCHIC and MOTAGUA FAULTS, GUATEMALA

CATALOG OF HISTORIC SEISMICITY IN THE VICINITY OF THE f CHIXOY-POLOCHIC AND MOTAGUA FAULTS, GUATEMALA Randall A. White U. S. Geological Survey Office of Earthquakes, Volcanoes and Engineering Branch of Seismology 345 Middlefield Road, MS 77 Menlo Park, CA 94025 FINAL REPORT for El Institute Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanologia, Meteorologia, e Hidrologia Guatemala City, Guatemala Open-File Report 84-88 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U. S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature, CATALOG OF HISTORIC SEISMICITY IN THE VICINITY OF THE CHIXOY-POLOCHIC AND MOTAGUA FAULTS, GUATEMALA ABSTRACT A new catalog of shallow historical earthquakes for the region of the Caribbean - North American plate boundary in Guatemala is presented. The catalog is drawn mostly from original official documents that are consi dered to be primary accounts. It contains 25 damaging earthquakes, 18 of which have not previously been published. The catalog is estimated to be complete for magnitude 6.5 earthquakes since 1700 for most of the study area. The earthquakes in this catalog can be grouped into periods of seismic activity alternating with extended periods of seismic quiescence as follows: 1538 large damaging earthquake 1560 (1539?) - 1702 1st quiet period no known damaging earthquakes 1702 - 1822 1st active period 18 damaging earthquakes 1822 - 1945 2nd quiet period no damaging earthquakes 1945 - 1983 2nd active period 6 damaging earthquakes The first active period terminated with the two part rupture of the eastern portion (M 7.3 to 7.5) of the Chixoy-Polochic fault in 1785 and the western portion (M 7.5 to 7.7) in 1816, followed by 5 years of regional aftershocks. -

Historia Y Memorias De La Comunidad Etnica Achi

... , - -· Historia y Memorias de la ,, Comunidad Etnica Achi Volumen 11 Versión Escolar Universidad Rafael Landívar Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia Instituto de Lingüística ,• El presente material fue elaborado con fondos aportados por el gobierno de Noruega, a través de UNICEF. Colección: Estudios Étnicos, No. 20 Área: Etnohistoria, No. 18 Serie: Castellano, No. 20 Directora de la colección: Guillermina Herrera Editor: Eleuterio Cahuec del Valle Equipo de escritores: Guillermina Herrera Anabella Giracca de Castellanos Roberto Díaz Castillo Guisela Mayén Eleuterio Cahuec del Valle Ilustrador: Javier Azurdia Diagramador: Javier Azurdia Asesor en Lingüística Maya: Eleuterio Cahuec del Valle Asesor en Historia: Roberto Díaz Castillo Asesora en Antropología: Guisela Mayén Apoyo en Informática: Carlos Rarael Figueroa © Universidad Rafael Landívar, 1997. ,-,.· -l ( , INDICE Comunidad étnica Achi .............................................................. 05 • ¿Y dónde estamos hoy? ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 08 • • Algunos hechos relevantes de nuestra historia......................... 09 • • • Memorias de nuestra comunidad .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 18 .., • 1 ~" ~ La comunidad étnica Achi En este largo recorrido que hemos realizado, en la lectura del volumen 1 "El Pueblo Maya de Guatemala: Veinticinco Siglos de Historia", hemos pasado por varios pueblos poseedores de grandes culturas distintas a la nuestra. Pero principalmente