Frequency of Occurrence for Units of Phonemes, Morae, and Syllables Appearing in a Lexical Corpus of a Japanese Newspaper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Man'yogana.Pdf (574.0Kb)

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The origin of man'yogana John R. BENTLEY Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 64 / Issue 01 / February 2001, pp 59 73 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X01000040, Published online: 18 April 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X01000040 How to cite this article: John R. BENTLEY (2001). The origin of man'yogana. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64, pp 5973 doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 131.156.159.213 on 05 Mar 2013 The origin of man'yo:gana1 . Northern Illinois University 1. Introduction2 The origin of man'yo:gana, the phonetic writing system used by the Japanese who originally had no script, is shrouded in mystery and myth. There is even a tradition that prior to the importation of Chinese script, the Japanese had a native script of their own, known as jindai moji ( , age of the gods script). Christopher Seeley (1991: 3) suggests that by the late thirteenth century, Shoku nihongi, a compilation of various earlier commentaries on Nihon shoki (Japan's first official historical record, 720 ..), circulated the idea that Yamato3 had written script from the age of the gods, a mythical period when the deity Susanoo was believed by the Japanese court to have composed Japan's first poem, and the Sun goddess declared her son would rule the land below. -

SUPPORTING the CHINESE, JAPANESE, and KOREAN LANGUAGES in the OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM by Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT the Asian L

SUPPORTING THE CHINESE, JAPANESE, AND KOREAN LANGUAGES IN THE OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM By Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT The Asian language versions of the OpenVMS operating system allow Asian-speaking users to interact with the OpenVMS system in their native languages and provide a platform for developing Asian applications. Since the OpenVMS variants must be able to handle multibyte character sets, the requirements for the internal representation, input, and output differ considerably from those for the standard English version. A review of the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean writing systems and character set standards provides the context for a discussion of the features of the Asian OpenVMS variants. The localization approach adopted in developing these Asian variants was shaped by business and engineering constraints; issues related to this approach are presented. INTRODUCTION The OpenVMS operating system was designed in an era when English was the only language supported in computer systems. The Digital Command Language (DCL) commands and utilities, system help and message texts, run-time libraries and system services, and names of system objects such as file names and user names all assume English text encoded in the 7-bit American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) character set. As Digital's business began to expand into markets where common end users are non-English speaking, the requirement for the OpenVMS system to support languages other than English became inevitable. In contrast to the migration to support single-byte, 8-bit European characters, OpenVMS localization efforts to support the Asian languages, namely Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, must deal with a more complex issue, i.e., the handling of multibyte character sets. -

A Look at Linguistic Readers

Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts Volume 10 Issue 3 April 1970 Article 5 4-1-1970 A Look At Linguistic Readers Nicholas P. Criscuolo New Haven, Connecticut Public Schools Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Criscuolo, N. P. (1970). A Look At Linguistic Readers. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 10 (3). Retrieved from https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons/vol10/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Education and Literacy Studies at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. A LOOK AT LINGUISTIC READERS Nicholas P. Criscuolo NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT, PUBLIC SCHOOLS Linguistics, as it relates to reading, has generated much interest lately among educators. Although linguistics is not a new science, its recent focus has captured the interest of the reading specialist because both the specialist and the linguist are concerned with language. This surge of interest in linguistics becomes evident when one sees that a total of forty-four articles on linguistics are listed in the Education Index for July, 1965 to June, 1966. The number of articles on linguistics written for educational journals has been increasing ever SInce. This interest has been sharpened to some degree by the publi cation of Chall's book Learning to Read: The Great Debate (1). -

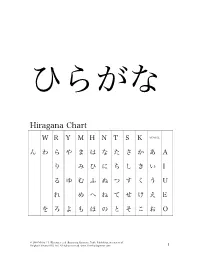

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

2 Mora and Syllable

2 Mora and Syllable HARUO KUBOZONO 0 Introduction In his classical typological study Trubetzkoy (1969) proposed that natural languages fall into two groups, “mora languages” and “syllable languages,” according to the smallest prosodic unit that is used productively in that lan- guage. Tokyo Japanese is classified as a “mora” language whereas Modern English is supposed to be a “syllable” language. The mora is generally defined as a unit of duration in Japanese (Bloch 1950), where it is used to measure the length of words and utterances. The three words in (1), for example, are felt by native speakers of Tokyo Japanese as having the same length despite the different number of syllables involved. In (1) and the rest of this chapter, mora boundaries are marked by hyphens /-/, whereas syllable boundaries are marked by dots /./. All syllable boundaries are mora boundaries, too, although not vice versa.1 (1) a. to-o-kyo-o “Tokyo” b. a-ma-zo-n “Amazon” too.kyoo a.ma.zon c. a-me-ri-ka “America” a.me.ri.ka The notion of “mora” as defined in (1) is equivalent to what Pike (1947) called a “phonemic syllable,” whereas “syllable” in (1) corresponds to what he referred to as a “phonetic syllable.” Pike’s choice of terminology as well as Trubetzkoy’s classification may be taken as implying that only the mora is relevant in Japanese phonology and morphology. Indeed, the majority of the literature emphasizes the importance of the mora while essentially downplaying the syllable (e.g. Sugito 1989, Poser 1990, Tsujimura 1996b). This symbolizes the importance of the mora in Japanese, but it remains an open question whether the syllable is in fact irrelevant in Japanese and, if not, what role this second unit actually plays in the language. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

A Student Model of Katakana Reading Proficiency for a Japanese Language Intelligent Tutoring System

A Student Model of Katakana Reading Proficiency for a Japanese Language Intelligent Tutoring System Anthony A. Maciejewski Yun-Sun Kang School of Electrical Engineering Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana 47907 Abstract--Thls work describes the development of a kanji. Due to the limited number of kana, their relatively low student model that Is used In a Japanese language visual complexity, and their systematic arrangement they do Intelligent tutoring system to assess a pupil's not represent a significant barrier to the student of Japanese. proficiency at reading one of the distinct In fact, the relatively small effort required to learn katakana orthographies of Japanese, known as k a t a k a n a , yields significant returns to readers of technical Japanese due to While the effort required to memorize the relatively the high incidence of terms derived from English and few k a t a k a n a symbols and their associated transliterated into katakana. pronunciations Is not prohibitive, a major difficulty In reading katakana Is associated with the phonetic This work describes the development of a system that is modifications which occur when English words used to automatically acquire knowledge about how English which are transliterated Into katakana are made to words are transliterated into katakana and then to use that conform to the more restrictive rules of Japanese information in developing a model of a student's proficiency in phonology. The algorithm described here Is able to reading katakana. This model is used to guide the instruction automatically acquire a knowledge base of these of the student using an intelligent tutoring system developed phonological transformation rules, use them to previously [6,8]. -

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II

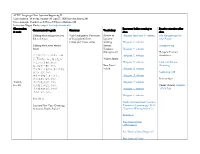

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II Class duration: 10 weeks, January 28–April 7, 2020 (no class March 24) Class meetings: Tuesdays at 5:30pm–7:30pm in Hellems 145 Instructor: Megan Husby, [email protected] Class session Resources before coming to Practice exercises after Communicative goals Grammar Vocabulary & topic class class Talking about things that you Verb Conjugation: Past tense Review of Hiragana Intro and あ column Fun Hiragana app for did in the past of long (polite) forms Japanese your Phone (~desu and ~masu verbs) Writing Hiragana か column Talking about your winter System: Hiragana song break Hiragana Hiragana さ column (Recognition) Hiragana Practice クリスマス・ハヌカー・お Hiragana た column Worksheet しょうがつ 正月はなにをしましたか。 Winter Sports どこにいきましたか。 Hiragana な column Grammar Review なにをたべましたか。 New Year’s (Listening) プレゼントをかいましたか/ Vocab Hiragana は column もらいましたか。 Genki I pg. 110 スポーツをしましたか。 Hiragana ま column だれにあいましたか。 Practice Quiz Week 1, えいがをみましたか。 Hiragana や column Jan. 28 ほんをよみましたか。 Omake (bonus): Kasajizō: うたをききましたか/ Hiragana ら column A Folk Tale うたいましたか。 Hiragana わ column Particle と Genki: An Integrated Course in Japanese New Year (Greetings, Elementary Japanese pgs. 24-31 Activities, Foods, Zodiac) (“Japanese Writing System”) Particle と Past Tense of desu (Affirmative) Past Tense of desu (Negative) Past Tense of Verbs Discussing family, pets, objects, Verbs for being (aru and iru) Review of Katakana Intro and ア column Katakana Practice possessions, etc. Japanese Worksheet Counters for people, animals, Writing Katakana カ column etc. System: Genki I pgs. 107-108 Katakana Katakana サ column (Recognition) Practice Quiz Katakana タ column Counters Katakana ナ column Furniture and common Katakana ハ column household items Katakana マ column Katakana ヤ column Katakana ラ column Week 2, Feb. -

Learning About Phonology and Orthography

EFFECTIVE LITERACY PRACTICES MODULE REFERENCE GUIDE Learning About Phonology and Orthography Module Focus Learning about the relationships between the letters of written language and the sounds of spoken language (often referred to as letter-sound associations, graphophonics, sound- symbol relationships) Definitions phonology: study of speech sounds in a language orthography: study of the system of written language (spelling) continuous text: a complete text or substantive part of a complete text What Children Children need to learn to work out how their spoken language relates to messages in print. Have to Learn They need to learn (Clay, 2002, 2006, p. 112) • to hear sounds buried in words • to visually discriminate the symbols we use in print • to link single symbols and clusters of symbols with the sounds they represent • that there are many exceptions and alternatives in our English system of putting sounds into print Children also begin to work on relationships among things they already know, often long before the teacher attends to those relationships. For example, children discover that • it is more efficient to work with larger chunks • sometimes it is more efficient to work with relationships (like some word or word part I know) • often it is more efficient to use a vague sense of a rule How Children Writing Learn About • Building a known writing vocabulary Phonology and • Analyzing words by hearing and recording sounds in words Orthography • Using known words and word parts to solve new unknown words • Noticing and learning about exceptions in English orthography Reading • Building a known reading vocabulary • Using known words and word parts to get to unknown words • Taking words apart while reading Manipulating Words and Word Parts • Using magnetic letters to manipulate and explore words and word parts Key Points Through reading and writing continuous text, children learn about sound-symbol relation- for Teachers ships, they take on known reading and writing vocabularies, and they can use what they know about words to generate new learning. -

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin Essay Title: The sound system of Japanese This essay aims to introduce the sound system of Japanese, including the inventories of consonants, vowels, and diphthongs. The phonological variations of the sound segments in different phonetic environments are also included. For the illustration, word examples are given and they are presented in the following format: [IPA] (Romaji: “meaning”). Consonants In Japanese, there are 14 core consonants, and some of them have a lot of allophonic variations. The various types of consonants classified with respect to their manner of articulation are presented as follows. Stop Japanese has six oral stops or plosives, /p b t d k g/, which are classified into three place categories, bilabial, alveolar, and velar, as listed below. In each place category, there is a pair of plosives with the contrast in voicing. /p/ = a voiceless bilabial plosive [p]: [ippai] (ippai: “A cup of”) /b/ = a voiced bilabial plosive [b]: [baɴ] (ban: “Night”) /t/ = a voiceless alveolar plosive [t]: [oto̞ ːto̞ ] (ototo: “Brother”) /d/ = a voiced alveolar plosive [d]: [to̞ mo̞ datɕi] (tomodachi: “Friend”) /k/ = a voiceless velar plosive [k]: [kaiɰa] (kaiwa: “Conversation”) /g/ = a voiced velar plosive [g]: [ɡakɯβsai] (gakusai: “Student”) Phonetically, Japanese also has a glottal stop [ʔ] which is commonly produced to separate the neighboring vowels occurring in different syllables. This phonological phenomenon is known as ‘glottal stop insertion’. The glottal stop may be realized as a pause, which is used to indicate the beginning or the end of an utterance. For instance, the word “Japanese money” is actually pronounced as [ʔe̞ ɴ], instead of [je̞ ɴ], and the pronunciation of “¥15” is [dʑɯβːɡo̞ ʔe̞ ɴ]. -

Product Catalog E-Book

Product Catalog E-Book Metallurgy Aerospace Composites Industrial The most trusted name in thermocouple wire www.tewire.com Quality Products, Innovative Solutions, Superior Service and Unmatched Experience High-Performance Wire and Cable Design Solutions What do the industrial, commercial and RF communication, aerospace and defense markets all have in common? Customers in these markets all require wire design solutions that fit their exact technical standards, from thermocouple and high-temperature wire to custom MIL spec cables. The seven companies that make up the Marmon High Performance Cable Group each provide highly engineered cables to meet the exacting standards these markets require. Read More. Collaboration Leads to Innovation in Wire and Cable Design In the wire and cable industry, customers have plenty of legacy products to choose from, so there isn’t much opportunity for innovative product development. To meet our customers’ needs in the most efficient way possible, we may try to reinvent/enhance older products or find applications that could lead to new wire and cable design products. Here are two skills that help manufacturers identify the best products and applications for their customers… Read More. Applying 6S Continuous Improvement to Shipping Have you ever been completing a task, deep in concentration, and suddenly you’re interrupted – a coworker with a question, you ran out of staples, you lost your pen – and now you’ve lost that concentration? It takes you extra time to get your train of thought back, and you’re more likely to make costly errors. Something so simple as a misplaced tool can distract anyone, whether in the office or on the shop floor, from the task at hand… Read More. -

Na Kana Magiti Kei Na Lotu

1 NA KANA MAGITI KEI NA LOTU (Vola Tabu : Maciu 22:1-10; Luke 14:12-24) Vola ko Rev. Dr. Ilaitia S. Tuwere. Sa inaki ni vunau oqo me taroga ka sauma talega na taro : A cava na Lotu? Ni da tekivu edaidai ena noda solevu vakalotu, sa na yaga meda taroga ka tovolea talega me sauma na taro oqori. Ia, ena levu na kena isau eda na solia, me vaka na: gumatuataki ni masu kei na vulici ni Vola Tabu, bula vakayalo, muria na ivakarau se lawa ni lotu ka vuqa tale. Na veika oqori era ka dina ka tu kina eso na isau ni taro : A Cava na Lotu. Na i Vola Tabu e sega ni tuvalaka vakavosa vei keda na ibalebale ni lotu. E vakavuqa me boroya vei keda na iyaloyalo me vakadewataka kina na veika eso e vinakata me tukuna. E sega talega ni solia e duabulu ga na iyaloyalo me baleta na lotu. E vuqa sara e solia vei keda. Oqori me vaka na Qele ni Sipi kei na i Vakatawa Vinaka; na Vuni Vaini kei na Tabana; na i Vakavuvuli kei iratou na nona Gonevuli se Tisaipeli, na Masima se Rarama kei Vuravura, na Ulu kei na Vo ni Yago taucoko, ka vuqa tale. Ena mataka edaidai, meda raica vata yani na iyaloyalo ni kana magiti. E rua na kena ivakamacala eda rogoca, mai na Kosipeli i Maciu kei na nei Luke. Na kana magiti se na solevu edua na ivakarau vakaitaukei. Eda soqoni vata kina vakaveiwekani ena noda veikidavaki kei na marau, kena veitalanoa, kena sere kei na meke, kena salusalu kei na kumuni iyau.