Jean Epstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michał Krzykawski, Zuzanna Szatanik Gender Studies in French

Michał Krzykawski, Zuzanna Szatanik Gender Studies in French Romanica Silesiana 8/1, 22-30 2013 Mi c h a ł Kr z y K a w s K i , zu z a n n a sz a t a n i K University of Silesia Gender Studies in French They are seen as black therefore they are black; they are seen as women, therefore, they are women. But before being seen that way, they first had to be made that way. Monique WITTIG 12 Within Anglo-American academia, gender studies and feminist theory are recognized to be creditable, fully institutionalized fields of knowledge. In France, however, their standing appears to be considerably lower. One could risk the statement that while in Anglo-American academic world, gender studies have developed into a valid and independent critical theory, the French academe is wary of any discourse that subverts traditional universalism and humanism. A notable example of this suspiciousness is the fact that Judith Butler’s Gen- der Trouble: Feminism and a Subversion of Identity, whose publication in 1990 marked a breakthrough moment for the development of both gender studies and feminist theory, was not translated into French until 2005. On the one hand, therefore, it seems that in this respect not much has changed in French literary studies since 1981, when Jean d’Ormesson welcomed the first woman, Marguerite Yourcenar, to the French Academy with a speech which stressed that the Academy “was not changing with the times, redefining itself in the light of the forces of feminism. Yourcenar just happened to be a woman” (BEASLEY 2, my italics). -

Department of Film & Media Studies Hunter College

Department of Film & Media Studies Jeremy S. Levine Hunter College - CUNY 26 Halsey St., Apt. 3 695 Park Ave, Rm. 433 HN Brooklyn, NY 11216 New York, NY 10065 Phone: 978-578-0273 Phone: 212-772-4949 [email protected] Fax: 212-650-3619 jeremyslevine.com EDUCATION M.F.A. Integrated Media Arts, Department of Film & Media Studies, Hunter College, expected May 2020 Thesis Title: The Life of Dan, Thesis Advisor: Kelly Anderson, Distinctions: S&W Scholarship, GPA: 4.0 B.S. Television-Radio: Documentary Studies, Park School of Communications, Ithaca College, 2006 Distinctions: Magna Cum Laude, Park Scholarship EMPLOYMENT Hunter College, 2019 Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Film & Media Studies Taught two undergraduate sections of Intro to Media Studies in spring 2019, averaging 6.22 out of 7 in the “overall” category in student evaluations, and teaching two sections of Intro to Media Production for undergraduates in fall 2019. Brooklyn Filmmakers Collective, 2006 – Present Co-Founder, Advisory Board Member Co-founded organization dedicated to nurturing groundbreaking films, generative feedback, and supportive community. Recent member films screened at the NYFF, Sundance, and Viennale, broadcast on Showtime, HBO, and PBS, and received awards from Sundance, Slamdance, and Tribeca. Curators from Criterion, BAM, Vimeo, The Human Rights Watch Film Festival, and Art 21 programmed a series of 10-year BFC screenings at theaters including the Lincoln Center, Alamo, BAM, and Nitehawk. Transient Pictures, 2006 – 2018 Co-Founder, Director, Producer Co-founded and co-executive directed an Emmy award-winning independent production company. Developed company into a $500K gross annual organization. Directed strategic development, secured clients, managed production teams, oversaw finances, and produced original feature films. -

General Index

General Index Italicized page numbers indicate figures and tables. Color plates are in- cussed; full listings of authors’ works as cited in this volume may be dicated as “pl.” Color plates 1– 40 are in part 1 and plates 41–80 are found in the bibliographical index. in part 2. Authors are listed only when their ideas or works are dis- Aa, Pieter van der (1659–1733), 1338 of military cartography, 971 934 –39; Genoa, 864 –65; Low Coun- Aa River, pl.61, 1523 of nautical charts, 1069, 1424 tries, 1257 Aachen, 1241 printing’s impact on, 607–8 of Dutch hamlets, 1264 Abate, Agostino, 857–58, 864 –65 role of sources in, 66 –67 ecclesiastical subdivisions in, 1090, 1091 Abbeys. See also Cartularies; Monasteries of Russian maps, 1873 of forests, 50 maps: property, 50–51; water system, 43 standards of, 7 German maps in context of, 1224, 1225 plans: juridical uses of, pl.61, 1523–24, studies of, 505–8, 1258 n.53 map consciousness in, 636, 661–62 1525; Wildmore Fen (in psalter), 43– 44 of surveys, 505–8, 708, 1435–36 maps in: cadastral (See Cadastral maps); Abbreviations, 1897, 1899 of town models, 489 central Italy, 909–15; characteristics of, Abreu, Lisuarte de, 1019 Acequia Imperial de Aragón, 507 874 –75, 880 –82; coloring of, 1499, Abruzzi River, 547, 570 Acerra, 951 1588; East-Central Europe, 1806, 1808; Absolutism, 831, 833, 835–36 Ackerman, James S., 427 n.2 England, 50 –51, 1595, 1599, 1603, See also Sovereigns and monarchs Aconcio, Jacopo (d. 1566), 1611 1615, 1629, 1720; France, 1497–1500, Abstraction Acosta, José de (1539–1600), 1235 1501; humanism linked to, 909–10; in- in bird’s-eye views, 688 Acquaviva, Andrea Matteo (d. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Pour Une Littérature-Monde En Français”: Notes for a Rereading of the Manifesto

#12 “POUR UNE LITTÉRATURE-MONDE EN FRANÇAIS”: NOTES FOR A REREADING OF THE MANIFESTO Soledad Pereyra CONICET – Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas Instituto de Investigaciones en Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales (UNLP – CONICET). Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad Nacional de La Plata – Argentina María Julia Zaparart Instituto de Investigaciones en Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales (UNLP – CONICET). Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad Nacional de La Plata – Argentina Illustration || Paula Cuadros Translation || Joel Gutiérrez and Eloise Mc Inerney 214 Article || Received on: 31/07/2014 | International Advisory Board’s suitability: 12/11/2014 | Published: 01/2015 License || Creative Commons Attribution Published -Non commercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. 452ºF Abstract || The manifesto “Pour une littérature-monde en français” (2007) questioned for the first time in a newspaper of record the classification of the corpus of contemporary French literature in terms of categories of colonial conventions: French literature and Francopohone literature. A re-reading of the manifesto allows us to interrogate the supplementary logic (in Derrida’s term) between Francophone literatures and French literature through analyzing the controversies around the manifesto and some French literary awards of the last decade. This reconstruction allows us to examine the possibilities and limits of the notions of Francophonie and world-literature in French. Finally, this overall critical approach is demonstrated in the analysis of Atiq Rahimi’s novel Syngué sabour. Pierre de patience. Keywords || French Literature | Francophonie | Transnational Literatures | Atiq Rahimi 215 The manifesto “Pour une littérature-monde en français” appeared in the respected French newspaper Le monde des livres in March NOTES 1 2007. -

2012-13 Humanities Undergraduate Stage 2 & 3 Module Handbook

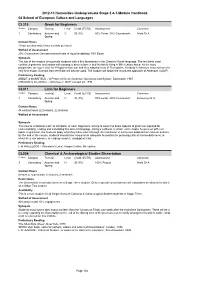

2012-13 Humanities Undergraduate Stage 2 & 3 Module Handbook 04 School of European Culture and Languages CL310 Greek for Beginners Version Campus Term(s) Level Credit (ECTS) Assessment Convenor 1 Canterbury Autumn and C 30 (15) 80% Exam, 20% Coursework Alwis Dr A Spring Contact Hours 1 hour seminar and 2 hour seminar per week Method of Assessment 20% Coursework (two assessment tests of equal weighting); 80% Exam Synopsis The aim of the module is to provide students with a firm foundation in the Classical Greek language. The text book used combines grammar and syntax with passages about a farmer and his family living in fifth-century Attica. As the story progresses, we move onto the Peloponnesian war and thus adapted texts of Thucydides. Reading is therefore ensured from the very first lesson. Extracts from the Bible will also be used. The module will follow the structured approach of Athenaze I (OUP). Preliminary Reading $%%27 0$16),(/' $3ULPHURI*UHHN*UDPPDU$FFLGHQFHDQG6\QWD[ 'XFNZRUWK 0%$/0( */$:$// $WKHQD]H, 283UHYLVHGHG CL311 Latin for Beginners Version Campus Term(s) Level Credit (ECTS) Assessment Convenor 1 Canterbury Autumn and C 30 (15) 80% Exam, 20% Coursework Keaveney Dr A Spring Contact Hours 44 contact hours (22 lectures, 22 classes) Method of Assessment Synopsis This course introduces Latin to complete, or near, beginners, aiming to cover the basic aspects of grammar required for understanding, reading and translating this ancient language. Using a textbook, in which each chapter focuses on different topics of grammar, the students apply what they have learnt through the translation of sentences adapted from ancient authors. -

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History Edited by Cornelia Wilhelm Volume 8 Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe Shared and Comparative Histories Edited by Tobias Grill An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-048937-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049248-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-048977-4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Grill, Tobias. Title: Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe : shared and comparative histories / edited by/herausgegeben von Tobias Grill. Description: [Berlin] : De Gruyter, [2018] | Series: New perspectives on modern Jewish history ; Band/Volume 8 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018019752 (print) | LCCN 2018019939 (ebook) | ISBN 9783110492484 (electronic Portable Document Format (pdf)) | ISBN 9783110489378 (hardback) | ISBN 9783110489774 (e-book epub) | ISBN 9783110492484 (e-book pdf) Subjects: LCSH: Jews--Europe, Eastern--History. | Germans--Europe, Eastern--History. | Yiddish language--Europe, Eastern--History. | Europe, Eastern--Ethnic relations. | BISAC: HISTORY / Jewish. | HISTORY / Europe / Eastern. Classification: LCC DS135.E82 (ebook) | LCC DS135.E82 J495 2018 (print) | DDC 947/.000431--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019752 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

Experiencing Literature 72

Udasmoro / Experiencing Literature 72 EXPERIENCING LITERATURE Discourses of Islam through Michel Houellebecq’s Soumission Wening Udasmoro Universitas Gadjah Mada [email protected] Abstract This article departs from the conventional assumption that works of literature are only texts to be read. Instead, it argues that readers bring these works to life by contextualizing them within themselves and draw from their own life experiences to understand these literary texts’ deeper meanings and themes. Using Soumission (Surrender), a controversial French novel that utilizes stereotypes in its exploration of Islam in France, this research focuses on the consumption of literary texts by French readers who are living or have lived in a country with a Muslim majority, specifically Indonesia. It examines how the novel’s stereotypes of Muslims and Islam are understood by a sample of French readers with experience living in Indonesia. The research problematizes whether a textual and contextual gap exists in their reading of the novel, and how they justify this gap in their social practices. In any reading of a text, the literal meaning (surface meaning) is taken as it is or the hidden meaning (deep meaning), but in a text that is covert in meaning, the reader may either venture into probing the underlying true meaning or accept the literal meaning of the text. However, this remains a point of contention and this research explores this issue using critical discourse analysis in Soumission’s text, in which the author presents the narrator’s views about Islam. The question that underpins this analysis is whether a reader’s life experiences and the context influence his or her view about Islam in interpreting Soumission’s text. -

27Th International Conference “European Heritage”

European Investment Casters’ Federation in association with Polish Foundry Research Institute Polish Foundrymen’s Association 27th International Conference “European Heritage” Under the patronage of the Ministry of Economy and the President of the City of Kraków Kraków, Poland 16-19 May, 2010 Specodlew Foundry Market Square, Kraków Auditorium Maximum CONTENTS Contents Welcome 4 Conference Information 7 Jagiellonian University 9 Kraków 10 Conference Programme 12 Exhibitors and Stand Numbers 15 Exhibitor Profiles 17 Technical Sessions 23 Delegate Visits 36 EICF Information 41 3 WELCOME developments in technology; from these it is hoped that the Welcome Address delegates will identify and develop their future strategies. As is also a tradition, the Suppliers Exhibition will be complementing the information provided by the technical sessions; sharing with us their latest developments and solutions. Once again their willingness to show their products and share their advances in technology plays a fundamental role for the conference. Finally the conference concludes with industrial and academic visits of major relevance; the Foundry Research Institute, the WSK foundry facility and the Rzeszów University of Technology. These visits provide the ideal complement to the conference sessions to help us understand the practical routes adopted by scientific research and the 21st century approach to the manufacture of investment castings. Getting together provides an element of value, and that by cooperation and networking we will get to know each other and this will give a personal element of value that will enrich us as individuals. There will be many moments during the conference to develop this personal approach but without any doubt the Conference Banquet provides a unique occasion to develop personal relationships. -

Anthology of Polish Poetry. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminars Abroad Program, 1998 (Hungary/Poland)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 444 900 SO 031 309 AUTHOR Smith, Thomas A. TITLE Anthology of Polish Poetry. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminars Abroad Program, 1998 (Hungary/Poland). INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 206p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020)-- Guides Classroom - Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Anthologies; Cultural Context; *Cultural Enrichment; *Curriculum Development; Foreign Countries; High Schools; *Poetry; *Poets; Polish Americans; *Polish Literature; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Poland; Polish People ABSTRACT This anthology, of more than 225 short poems by Polish authors, was created to be used in world literature classes in a high school with many first-generation Polish students. The following poets are represented in the anthology: Jan Kochanowski; Franciszek Dionizy Kniaznin; Elzbieta Druzbacka; Antoni Malczewski; Adam Mickiewicz; Juliusz Slowacki; Cyprian Norwid; Wladyslaw Syrokomla; Maria Konopnicka; Jan Kasprowicz; Antoni Lange; Leopold Staff; Boleslaw Lesmian; Julian Tuwim; Jaroslaw Iwaszkiewicz; Maria Pawlikowska; Kazimiera Illakowicz; Antoni Slonimski; Jan Lechon; Konstanty Ildefons Galczynski; Kazimierz Wierzynski; Aleksander Wat; Mieczyslaw Jastrun; Tymoteusz Karpowicz; Zbigniew Herbert; Bogdan Czaykowski; Stanislaw Baranczak; Anna Swirszczynska; Jerzy Ficowski; Janos Pilinsky; Adam Wazyk; Jan Twardowski; Anna Kamienska; Artur Miedzyrzecki; Wiktor Woroszlyski; Urszula Koziol; Ernest Bryll; Leszek A. Moczulski; Julian Kornhauser; Bronislaw Maj; Adam Zagajewskii Ferdous Shahbaz-Adel; Tadeusz Rozewicz; Ewa Lipska; Aleksander Jurewicz; Jan Polkowski; Ryszard Grzyb; Zbigniew Machej; Krzysztof Koehler; Jacek Podsiadlo; Marzena Broda; Czeslaw Milosz; and Wislawa Szymborska. (BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. Anthology of Polish Poetry. Fulbright Hays Summer Seminar Abroad Program 1998 (Hungary/Poland) Smith, Thomas A. -

Zanikanie I Istnienie Niepełne

Zanikanie i istnienie niepełne W labiryntach romantycznej i współczesnej podmiotowości NR 3108 Zanikanie i istnienie niepełne W labiryntach romantycznej i współczesnej podmiotowości pod redakcją Aleksandry Dębskiej-Kossakowskiej Pawła Paszka Leszka Zwierzyńskiego Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego Katowice 2013 Redaktor serii: Studia o Kulturze Dobrosława Wężowicz-Ziółkowska Recenzent Jarosław Ławski Spis treści Wstęp (Leszek Zwierzyński, Paweł Paszek) . 7 ROMANTYCZNE ZAŁOŻENIE – W STRONĘ PODMIOTOWOŚCI NOWOCZESNEJ Leszek Zwierzyński „Ja” poetyckie Słowackiego – próba ujęcia konstelacyjnego . 15 Lucyna Nawarecka Ja – Duch. O podmiocie Króla-Ducha . 53 Agata Seweryn Słowacki i świerszcze . 65 Dariusz Seweryn Maria bez podmiotu. Powieść poetycka Antoniego Malczewskiego jako utwór epicki . 83 PODMIOTOWOŚĆ I EKSCES Włodzimierz Szturc Pisanie jest doszczętne – Antonin Artaud . 113 Kamila Gęsikowska Doświadczenie postrzegania pozazmysłowego – przypadek Agni Pilch . 129 Magdalena Bisz „Ja” psychotyczne – „ja” twórcze. O Aurelii Gerarda de Nervala . 145 6 Spis treści PRZEKROCZENIA: NOWOCZESNOŚĆ I PONOWOCZESNOŚĆ Magdalena Saganiak Bourne. Podmiotowość znaleziona na marginesie, czyli o meta- fizyce w sztuce masowej . 169 Tomasz Gruszczyk We wstecznym lusterku. Konstytuowanie podmiotu w prozie Zyg- munta Haupta . 191 Paweł Paszek Modlitwa i nieobecność. Poe-teo-logia Ryszarda Krynickiego . 211 Alina Świeściak Przygodne tożsamości Andrzeja Sosnowskiego . 235 Indeks nazw osobowych . 249 Wstęp Niniejsza książka stanowi próbę (cząstkową, ograniczoną) -

Late Poetry of Tadeusz Różewicz

Modes of Reading Texts, Objects, and Images: Late Poetry of Tadeusz Różewicz by Olga Ponichtera A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures University of Toronto © Copyright by Olga Ponichtera 2015 Modes of Reading Texts, Objects, and Images: Late Poetry of Tadeusz Różewicz Olga Ponichtera Doctor of Philosophy Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures University of Toronto 2015 Abstract This dissertation explores the late oeuvre of Tadeusz Różewicz (1921-2014), a world- renowned Polish poet, dramatist, and prose writer. It focuses primarily on three poetic and multi-genre volumes published after the political turn of 1989, namely: Mother Departs (Matka Odchodzi) (1999), professor’s knife (nożyk profesora) (2001), and Buy a Pig in a Poke: work in progress (Kup kota w worku: work in progress) (2008). The abovementioned works are chosen as exemplars of the writer’s authorial strategies / modes of reading praxis, prescribed by Różewicz for his ideal audience. These strategies simultaneously reveal the poet himself as a reader (of his own texts and the works of other authors). This study defines an author’s late style as a response to the cognitive and aesthetic evaluation of one’s life’s work, artistic legacy, and metaphysical angst of mortality. Różewicz’s late works are characterized by a tension between recognition and reconciliation to closure, and difficulty with it and/or opposition to it. Authorial construction of lyrical subjectivity as a reader, and modes of textual construction are the central questions under analysis. This study examines both, Tadeusz Różewicz as a reader, and the authorial strategies/ modes he creates to guide the reading praxis of the authorial audience.