Apartheid Vs. Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISSERTATION O Attribution

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/vital/access/manager/Index?site_name=Research%20Output (Accessed: Date). The design of a vehicular traffic flow prediction model for Gauteng freeways using ensemble learning by TEBOGO EMMA MAKABA A dissertation submitted in fulfilment for the Degree of Magister Commercii in Information Technology Management Faculty of Management UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG Supervisor: Dr B.N Gatsheni 2016 DECLARATION I certify that the dissertation submitted by me for the degree Master’s of Commerce (Information Technology Management) at the University of Johannesburg is my independent work and has not been submitted by me for a degree at another university. TEBOGO EMMA MAKABA i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I hereby wish to express my gratitude to the following individuals who enabled this document to be successfully and timeously completed: Firstly, GOD Supervisor, Dr BN Gatsheni Mikros Traffic Monitoring(Pty) Ltd (MTM) for providing me with the traffic flow data My family and friends Prof M Pillay and Ms N Eland Faculty of Management for funding me with the NRF Supervisor linked bursary ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to everyone who supported me during the project, from the start till the end. -

Trouble Flares up at Mabieskraal

, 8 .~ · le bv si b k ' d" I£tl1l1l1ll1l1l1l1ll1l"""III1I1I11I11I11 I1 " II " II I1I1 I11 I1 " ~l l11 l1 m lll IIIIII III Bantustan IS rue Y slam 0 In Isgulse ... 1• ••• •• ••• 1 Congress reiects the concept of national homes § for Africans ...We claim the whole of South Africa as our home Vol. 5, No, 51 Registered. at the G.P.O. as a Newspaper 6di= _ SOUTHERNEDITION Thursday, October 8, 1959 • 5 ~1I"1II"III11I1I11I11I1I11I11I1 I1I11" nllllll lllllll lll ll ll ll ll ll ll ll lll l lll lll lll lll ll ll ll lll lll lll ll lllll ll ll ll ll lll ll l1 1I 111 11111 11 ~ oWHAT KH USCHOV TOLD THE U.S.A. The verbatim record no other news Slap In The Face For E~ic Louw paper in South Africa has printed JOHANNESBURG as their home", Iin South Africa during the last two B~~~~~ aF~:~naft~i~1~~~ whT: ~[r~~e s~b~ftt~J~~~f~:~~~ ye~~~l i n g ~ith so-called Ban.tusta!1s ~r. Eric Louw had mad.e ,bis ~:~~ r:, i ~ s ~~o ~i v~f t~~e A9ri~~~a~i~~: ~o~~r~~~~~l s ~:dt e~~ ~ h~ f ~h~ o~~~I~ ~ .- Pages 4 and 5 big speech to U.N: D., claiming point on trends and developments Continued 011 page 7 that the Bantu territories would 1 -------------------- I(!1:~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ eventually form part of a South African Commonwealth toge ther with White South Africa, the African National Congress has sent a memorandum to ~;:t~' :he:~ri~i::tu~~~n ~~~~:; as a gigantic fraud. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

The Referendum in FW De Klerk's War of Manoeuvre

The referendum in F.W. de Klerk’s war of manoeuvre: An historical institutionalist account of the 1992 referendum. Gary Sussman. London School of Economics and Political Science. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government and International History, 2003 UMI Number: U615725 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615725 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 T h e s e s . F 35 SS . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract: This study presents an original effort to explain referendum use through political science institutionalism and contributes to both the comparative referendum and institutionalist literatures, and to the political history of South Africa. Its source materials are numerous archival collections, newspapers and over 40 personal interviews. This study addresses two questions relating to F.W. de Klerk's use of the referendum mechanism in 1992. The first is why he used the mechanism, highlighting its role in the context of the early stages of his quest for a managed transition. -

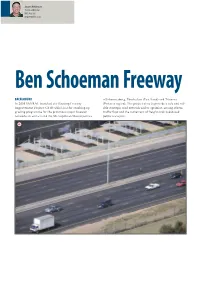

Ben Schoeman Freeway

Jurgens Weidemann Technical Director BKS (Pty) Ltd [email protected] Ben Schoeman Freeway BACKGROUND of Johannesburg, Ekurhuleni (East Rand) and Tshwane In 2008 SANRAL launched the Gauteng Freeway (Pretoria region). The project aims to provide a safe and reli- Improvement Project (GFIP) which is a far-reaching up- able strategic road network and to optimise, among others, grading programme for the province’s major freeway traffic flow and the movement of freight and road-based networks in and around the Metropolitan Municipalities public transport. 1 The GFIP is being implemented in phases. The first phase 1 Widened to five lanes per carriageway comprises the improvement of approximately 180 km of 2 Bridge widening at the Jukskei River existing freeways and includes 16 contractual packages. The 3 Placing beams at Le Roux overpass network improvement comprises the adding of lanes and up- 4 Brakfontein interchange – adding a third lane grading of interchanges. Th e upgrading of the Ben Schoeman Freeway (Work Package 2 C of the GFIP) is described in this article. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES Th e upgraded and expanded freeways will signifi cantly re- duce traffi c congestion and unblock access to economic op- portunities and social development projects. Th e GFIP will provide an interconnected freeway system between the City of Johannesburg and the City of Tshwane, this system currently being one of the main arteries within the north-south corridor. One of the most significant aims of this investment for ordinary citizens is the reduction of travel times since many productive hours are wasted as a result of long travel times. -

Fascist Or Opportunist?”: the Political Career of Oswald Pirow, 1915–1943

Historia, 63, 2, November 2018, pp 93-111 “Fascist or opportunist?”: The political career of Oswald Pirow, 1915–1943 F.A. Mouton* Abstract Oswald Pirow’s established place in South African historiography is that of a confirmed fascist, but in reality he was an opportunist. Raw ambition was the underlying motive for every political action he took and he had a ruthless ability to adjust his sails to prevailing political winds. He hitched his ambitions to the political momentum of influential persons such as Tielman Roos and J.B.M. Hertzog in the National Party with flattery and avowals of unquestioning loyalty. As a Roos acolyte he was an uncompromising republican, while as a Hertzog loyalist he rejected republicanism and national-socialism, and was a friend of the Jewish community. After September 1939 with the collapse of the Hertzog government and with Nazi Germany seemingly winning the Second World War, overnight he became a radical republican, a national-socialist and an anti-Semite. The essence of his political belief was not national-socialism, but winning, and the opportunistic advancement of his career. Pirow’s founding of the national-socialist movement, the New Order in 1940 was a gamble that “went for broke” on a German victory. Keywords: Oswald Pirow; New Order; fascism; Nazi Germany; opportunism; Tielman Roos; J.B.M. Hertzog; ambition; Second World War. Opsomming In die Suid-Afrikaanse historiografie word Oswald Pirow getipeer as ’n oortuigde fascis, maar in werklikheid was hy ’n opportunis. Rou ambisie was die onderliggende motivering van alle politieke handelinge deur hom. Hy het die onverbiddelike vermoë gehad om sy seile na heersende politieke winde te span. -

Die Burger Se Rol in Die Suid-Afrikaanse Partypolitiek, 1934 - 1948

DIE BURGER SE ROL IN DIE SUID-AFRIKAANSE PARTYPOLITIEK, 1934 - 1948 deur JURIE JACOBUS JOUBERT voorgelê luidens die vereistes vir die graad D. LITT ET PHIL in die vak GESKIEDENIS aan die UNIVERSITEIT VAN SUID-AFRIKA PROMOTOR: PROFESSOR C.F.J. MULLER MEDE-PROMOTOR: PROFESSOR J.P. BRITS JUNIE 1990 THE PRESENCE GF DIE BURGER IN THE PARTYPOLITICS DF SOUTH AFRICA, 1934 - 1948 by JURIE JACOBUS JOUBERT Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER : PROFESSOR C.F.J. MULLER JOINT PROMOTER : PROFESSOR J.P. BRITS JUNE 1990 U N f S A BIBLIOTPPK AS9U .1 a Class KÍas ..J & t e Access I Aanwin _ 01326696 "Ek verklaar hiermee dat Die Burger se rol in die Suid-Afrikaanse Partypolitiek, 1934 - 1948 my eie werk is en dat ek alle bronne wat ek gebruik of aangehaal het deur middel van volledige verwyeyigs aangecfyi en erken het" lU t (i) SUMMARY During the nineteen thirties and forties the Afrikaans newspaper Die Burger occupied a prominent place within the ambience of the South African press. Without reaching large circulation figures, it achieved recognition and respect because - apart from other reasons - it commanded the skills of a very competent editorial staff and management team. The way in which it effectively ousted its main rival Die Suiderstem, is testimony of its power and influence, particularly in its hinterland. The close association between Die Burger and the Cape National Party represented a formidable joining of forces. This relation ship, entailing mutual advantages, was sustained significantly by the involvement of Dr. -

Ben Schoeman.Indd

TP2039091 (1811-1886) BEN BEN SCHOEMAN SCHOEMAN FRANZ LISZT Après une Lecture du Dante: 19:04 1 Vallée d’Obermann Fantasia quasi Sonata (Années de Pèlerinage, Second year, Italy, S.161) 15:18 Les jeux d’eaux à la Villa d’Este 2 (Années de Pèlerinage, Endler Hall, First year, Switzerland, S.160) South Africa 9:23 Sonata in B minor, S.178 3 LISZT Recorded at: (Années de Pèlerinage,: 77:05 Third year, S.163) Total Luis Magalhães 33:18 on DecemberBen Schoeman18 - 21, 2010 (piano)Gerhard Roux 4 Stellenbosch University Artists: Gerhard Roux Produced by: W. Heuer Musikhaus Tim Lengfeld Balance engineer: Glitz-design Studio 1B Piano tuner: Justin Versfeld, Leon van Zyl Edited and Mixed Masteredby: by: Graphic Design:Photography: 2011 Standard Bank Young Artist for Music Assistants: Bösendorfer 280 concert piano BBenen SSchoeman.inddchoeman.indd SpreadSpread 1 ofof 6 - PPages(12,ages(12, 1)1) 111/03/281/03/28 12:2912:29 Switzerland, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic and the United Kingdom. Born into a musical family, Ben Schoeman studied the piano from a young age under the guidance of Joseph LISZT Stanford in Pretoria. After winning all the national music competitions in South Africa he moved to Italy, where he studied with Michel Dalberto, Louis Lortie and Boris Petrushansky at the Accademia His performance Pianistica ‘Incontri col Maestro’ in Imola. of Brahms’ Second There he obtained a Master Concert Piano Concerto with Diploma together with a MMus Degree the Cape Philharmonic in Performing Arts (cum laude) from the Orchestra was described as University of Pretoria. -

Albert Hertzog's “Calvinist Speech” and the Verlig

62 AUTHOR: ALBERT HERTZOG’S “CALVINIST Weronika Muller1 AFFILIATION: SPEECH” AND THE VERLIG- 1Doctoral student, VERKRAMPSTRYD: THE ORIGINS Department of History, OF THE RIGHT-WING MOVEMENT University of South Africa IN SOUTH AFRICA EMAIL: [email protected] DOI: https://dx.doi. ABSTRACT org/10.18820/24150509/ SJCH46.v1.4 This article analyses the role Dr Albert Hertzog, an ultra- conservative Afrikaner Nationalist, played in the formation ISSN 0258-2422 (Print) of South Africa’s right-wing movement. It focuses on ISSN 2415-0509 (Online) his “Calvinist speech” of 1969 due to its historical Southern Journal for significance for the unity of the National Party (NP) and as a broad summary of Hertzog’s personal opinion Contemporary History on the politics of South Africa. The speech contrasted 2021 46(1):62-85 liberal English with Calvinistic Afrikaners and concluded that only an Afrikaner true to Calvinistic principles could PUBLISHED: succeed in leading the nation through the perilous times 23 July 2021 they were facing. This opinion was considered offensive to the English population as well as to “enlightened” Nationalists like the Prime Minister, John Vorster. The article will examine how the controversy surrounding the speech precipitated a split in the NP; those expelled formed a right-wing party that failed to gain considerable support. When apartheid was being dismantled in the early 1990s, the movement did not pose a serious threat to the ruling party despite vows that Afrikaners would never surrender their power but rather fight to the bitter end. The failure of these ultra-conservatives originated in the verlig-verkrampstryd of the 1960s, in which Hertzog played a significant role. -

(M1) ENJO Consultants Centurion Close 119 Gerhard Street

ENJO Consultants FROM JOHANNESBURG (M1) Centurion Close Tel: (012) 667‐1985 Cell: 084 620 0437 1. Follow M1 and Ben Schoeman Fwy/Pretoria Main Rd to Jean 119 Gerhard Street Ave/M34 in LytteltonAH, Centurion. Centurion, Gauteng, South Africa 2. Take exit 329 from Ben Schoeman Fwy/Pretoria Main Rd/N14 GPS coordinates: S 25.84698 E 28.19044 Web: www.enjoconsultants.co.za 3. Merge onto M1 (Partial toll rd) Email: [email protected] 4. Continue onto Ben Schoeman Fwy/Pretoria Main Rd/N1 (Toll rd) 5. Keep right to continue on Ben Schoeman Fwy/Pretoria Main Rd 6. Continue onto Ben Schoeman Fwy/Pretoria Main Rd/N14 7. Use the left 2 lanes to take exit 329 for M34/Jean Avenue toward Centurion 8. Keep right at the fork to continue toward Jean Ave/M34 9. Continue on Jean Ave/M34. Take Rabie St/M19 and Von Willich N Ave to Gerhard St/M25 in Die Hoewes 10. Use any lane to turn right onto Jean Ave/M34 11. Use the right 2 lanes to turn right onto Rabie St/M19 12. At the roundabout, take the 1st exit onto Von Willich Ave 13. Turn left onto Gerhard St/M25 14. Destination will be on the left. 15. ENJO Consultants is next to Centurion Academy Somatology & Day Spa. From Johannesburg, M1 ENJO Consultants FROM PRETORIA VIA BOTHA AVENUE Centurion Close Tel: (012) 667‐1985 Cell: 084 620 0437 1. From Christina De Wit Ave continue onto Botha Ave/M18 119 Gerhard Street 2. Turn right onto Cantonments Rd/M19 Centurion, Gauteng, South Africa 3. -

The Rise of the South African Reich

The Rise of the South African Reich http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp3b10036 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The Rise of the South African Reich Author/Creator Bunting, Brian; Segal, Ronald Publisher Penguin Books Date 1964 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, Germany Source Northwestern University Libraries, Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, 960.5P398v.12cop.2 Rights By kind permission of Brian P. Bunting. Description "This book is an analysis of the drift towards Fascism of the white government of the South African Republic. -

The African Patriots, the Story of the African National Congress of South Africa

The African patriots, the story of the African National Congress of South Africa http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp3b10002 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The African patriots, the story of the African National Congress of South Africa Author/Creator Benson, Mary Publisher Faber and Faber (London) Date 1963 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Source Northwestern University Libraries, Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, 968 B474a Description This book is a history of the African National Congress and many of the battles it experienced.