Albert Hertzog's “Calvinist Speech” and the Verlig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Conscription in South Africa, 1952-1972

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 35, Nr 1, 2007. doi: 10.5787/35-1-29 46 PATRIOTIC DUTY OR RESENTED IMPOSITION? PUBLIC REACTIONS TO MILITARY CONSCRIPTION IN WHITE SOUTH AFRICA, 1952-1972 __________________________________ Graeme Callister Department of History, University of Stellenbosch1 Introduction It is widely known that from the introduction of the Defence Amendment Act of 1967 (Act no. 85 of 1967) until the fall of apartheid in 1994, South Africa had a system of universal national service for white males, and that the men conscripted into the South African Defence Force (SADF) under this system were engaged in conflicts in Namibia, Angola, and later in the townships of South Africa itself. What is widely ignored however, both in academia and in wider society, is that the South African military relied on conscripts, selected through a ballot system, to fill its ranks for some fifteen years before the introduction of universal service. This article intends to redress this scholastic imbalance. The period of universal military service coincides with the period that saw South Africa in the world’s spotlight, when defeating apartheid was the great crusade in which capitalist and communist alike could engage. It is therefore not surprising that the military of that era has also been studied. Post-1967 universal national service in South Africa has received some attention from scholars, and is generally portrayed as a resented imposition at best. Resistance to conscription is widely covered, especially through the 1980s when organisations such as the Conscientious Objectors Support Group (COSG, formed in 1980) and the End Conscription Campaign (ECC, formed in 1983) gave a more public ‘face’ to the anti-conscription movement.2 However, as can be seen from the relatively late 1 I would like to extend my gratitude to Professor Albert Grundlingh of the University of Stellenbosch for his comments and advice on the first draft of this article. -

DISSERTATION O Attribution

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/vital/access/manager/Index?site_name=Research%20Output (Accessed: Date). The design of a vehicular traffic flow prediction model for Gauteng freeways using ensemble learning by TEBOGO EMMA MAKABA A dissertation submitted in fulfilment for the Degree of Magister Commercii in Information Technology Management Faculty of Management UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG Supervisor: Dr B.N Gatsheni 2016 DECLARATION I certify that the dissertation submitted by me for the degree Master’s of Commerce (Information Technology Management) at the University of Johannesburg is my independent work and has not been submitted by me for a degree at another university. TEBOGO EMMA MAKABA i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I hereby wish to express my gratitude to the following individuals who enabled this document to be successfully and timeously completed: Firstly, GOD Supervisor, Dr BN Gatsheni Mikros Traffic Monitoring(Pty) Ltd (MTM) for providing me with the traffic flow data My family and friends Prof M Pillay and Ms N Eland Faculty of Management for funding me with the NRF Supervisor linked bursary ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to everyone who supported me during the project, from the start till the end. -

North Africa, South Africa

North Africa POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS International Relations T -LHE YEAR was marked by greater rapprochement among the coun- tries of North Africa. Old disputes were settled or were on the way to settle- ment, and agreements for cooperation were developed. There was also a general improvement in relations between the countries of North Africa and nations outside the immediate area. However, there was increased anti-Israel activity, primarily on the diplomatic and public-relations fronts. A development of potential importance, but one whose effects could not yet be assessed fully, was the overthrow in September of King Idris of Libya by a group of young officers under strong Egyptian influence. Treaties of solidarity and cooperation were signed between Tunisia and Morocco, in January, and between Algeria and Libya, in February. When President Houari Boumedienne of Algeria visited King Hassan of Morocco to draw up the document, Hassan used the occasion to emphasize the im- portance of unity and regional agreements for the development of the Arab countries and the preservation of their freedom against outside aggression, particularly by Israel. Negotiations for a similar treaty between Algeria and Tunisia began in January, a year behind schedule, but there were difficulties because Tunisia gave asylum to Algerian political refugees and because the Tunisian press charged that there were Soviet bases in Algeria. Not until December was there an announcement that complete agreement had been reached on "all pending questions," apparently including disagreements on the delineation of the frontier. A number of international conferences took place in Algeria and Morocco in 1969. The annual conference of African ministers of labor, meeting in Algiers in March, called for a boycott of cargoes coming from South Africa, Portugal, and Israel, a demand which, however, failed to win the support of several countries from other parts of the continent. -

Trouble Flares up at Mabieskraal

, 8 .~ · le bv si b k ' d" I£tl1l1l1ll1l1l1l1ll1l"""III1I1I11I11I11 I1 " II " II I1I1 I11 I1 " ~l l11 l1 m lll IIIIII III Bantustan IS rue Y slam 0 In Isgulse ... 1• ••• •• ••• 1 Congress reiects the concept of national homes § for Africans ...We claim the whole of South Africa as our home Vol. 5, No, 51 Registered. at the G.P.O. as a Newspaper 6di= _ SOUTHERNEDITION Thursday, October 8, 1959 • 5 ~1I"1II"III11I1I11I11I1I11I11I1 I1I11" nllllll lllllll lll ll ll ll ll ll ll ll lll l lll lll lll lll ll ll ll lll lll lll ll lllll ll ll ll ll lll ll l1 1I 111 11111 11 ~ oWHAT KH USCHOV TOLD THE U.S.A. The verbatim record no other news Slap In The Face For E~ic Louw paper in South Africa has printed JOHANNESBURG as their home", Iin South Africa during the last two B~~~~~ aF~:~naft~i~1~~~ whT: ~[r~~e s~b~ftt~J~~~f~:~~~ ye~~~l i n g ~ith so-called Ban.tusta!1s ~r. Eric Louw had mad.e ,bis ~:~~ r:, i ~ s ~~o ~i v~f t~~e A9ri~~~a~i~~: ~o~~r~~~~~l s ~:dt e~~ ~ h~ f ~h~ o~~~I~ ~ .- Pages 4 and 5 big speech to U.N: D., claiming point on trends and developments Continued 011 page 7 that the Bantu territories would 1 -------------------- I(!1:~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ eventually form part of a South African Commonwealth toge ther with White South Africa, the African National Congress has sent a memorandum to ~;:t~' :he:~ri~i::tu~~~n ~~~~:; as a gigantic fraud. -

Welcome to KPMG Crescent

Jan Smuts Ave St Andrews M1 Off Ramp Winchester Rd Jan Smuts Off Ramp Welcome to KPMGM27 Crescent M1 North On Ramp De Villiers Graaff Motorway (M1) 85 Empire Road, Parktown St Andrews Rd Albany Rd GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.18548 | Longitude: 28.045142 85 Empire Road, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 B M1 North On Ramp Directions: From Sandton/Pretoria M1 South Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg On Ramp Jan Smuts / Take Empire off ramp, at the robot turn left to the KPMG main St Andrews gate. (NB – the Empire entrance is temporarily closed). Continue Off Ramp to Jan Smuts Avenue, turn left and then first left into entrance on Empire Jan Smuts. M1 Off Ramp From South of JohannesburgWellington Rd /M2 Sky Bridge 4th Floor Take M1 (North) towards Sandton/Pretoria Take Exit 14A for Jan Smuts Avenue toward M27 and turn right M27 into Jan Smuts. At Empire Road turn right, at first traffic lights M1 South make a U-turn and travel back on Empire, and left into Jan Smuts On Ramp M17 Jan Smuts Ave Avenue, and first left into entrance. Empire Rd KPMG Entrance KPMG Entrance temporarily closed Off ramp On ramp T: +27 (0)11 647 7111 Private Bag 9, Jan Jan Smuts Ave F: +27 (0)11 647 8000 Parkview, 2122 E m p ire Rd Welcome to KPMG Wanooka Place St Andrews Rd, Parktown NORTH GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.182416 | Longitude: 28.03816 St Andrews Rd, Parktown, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 St Andrews Off Ramp Jan Smuts Ave Directions: Winchester Rd From Sandton/Pretoria Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg Take St Andrews off ramp, at the robot drive straight to the KPMG Jan Smuts main gate. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

The White Opposition Splits

12 THE WHITE OPPOSITION SPLITS STANLEY UYS Political Correspondent of the 'Sunday Times1 THE annual congress of the official South African Parliamentary Opposition or United Party in August last year, on the eve of the Provincial Elections, resulted in the resignation of almost a quarter of its Members of Parliament and the formation of a new white political party—the Progressives. Amidst the exhuma tions and excuses, analyses and adjustments that followed, two highly significant conclusions emerged—the official Parliamentary Opposition has swung substantially to the right, narrowing the already narrow gap between Government and United Party on the doctrines of race rule; and, for the first time in South African history, a substantial white Parliamentary Party with wide, if not dominant, electoral support in many urban areas, had come into existence specifically in order to propagate a more liberal policy in race relations. The origin of the Progressive break must be sought in the right-wing ''rethinking" resulting from the total failure of the United Party to avoid a steady electoral decline during the n years in which it has been in Opposition. In 1948, the Nationalist Party came to power with a majority of fewer than half-a-dozen M.P.s. Today, it has two-thirds of the House of Assembly, partly due to the completely one-sided character of the electoral system (particularly delimitation methods) and partly to the growing numerical superiority of the Afrikaner. It did not take the United Party long to evolve the view that there was no profit in battering its head against a stone wall, and that the only chance of success lay in winning over "moderate'' Nationalist voters. -

The Referendum in FW De Klerk's War of Manoeuvre

The referendum in F.W. de Klerk’s war of manoeuvre: An historical institutionalist account of the 1992 referendum. Gary Sussman. London School of Economics and Political Science. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government and International History, 2003 UMI Number: U615725 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615725 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 T h e s e s . F 35 SS . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract: This study presents an original effort to explain referendum use through political science institutionalism and contributes to both the comparative referendum and institutionalist literatures, and to the political history of South Africa. Its source materials are numerous archival collections, newspapers and over 40 personal interviews. This study addresses two questions relating to F.W. de Klerk's use of the referendum mechanism in 1992. The first is why he used the mechanism, highlighting its role in the context of the early stages of his quest for a managed transition. -

TV on the Afrikaans Cinematic Film Industry, C.1976-C.1986

Competing Audio-visual Industries: A business history of the influence of SABC- TV on the Afrikaans cinematic film industry, c.1976-c.1986 by Coenraad Johannes Coetzee Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art and Sciences (History) in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Anton Ehlers December 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za THESIS DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. December 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS Historical research frequently requires investigations that have ethical dimensions. Although not to the same extent as in medical experimentation, for example, the social sciences do entail addressing ethical considerations. This research is conducted at the University of Stellenbosch and, as such, must be managed according to the institution’s Framework Policy for the Assurance and Promotion of Ethically Accountable Research at Stellenbosch University. The policy stipulates that all accumulated data must be used for academic purposes exclusively. This study relies on social sources and ensures that the university’s policy on the values and principles of non-maleficence, scientific validity and integrity is followed. All participating oral sources were informed on the objectives of the study, the nature of the interviews (such as the use of a tape recorder) and the relevance of their involvement. -

Fadiga-Stewart Leslie Diss.Pdf (954.6Kb)

THE GENDER GAP IN AFRICAN PARTY SYSTEMS by Leslie Ann Fadiga-Stewart, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN POLITICAL SCIENCE Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Dennis Patterson Chairperson of the Committee John Barkdull Glen Biglasier Ambassador Tibor Nagy, Jr. Accepted John Borrelli Dean of the Graduate School August, 2007 Copyright 2007, Leslie Ann Fadiga-Stewart Texas Tech University, Leslie Fadiga-Stewart, August 2007 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It was a joy working with my advisor, Dr. Dennis Patterson. He provided valuable guidance and assistance and made this whole process easier because he was so supportive, understanding, and generous with his time. He saw my research project as an opportunity to learn something new and his positive attitude, infinite patience, and constant support are gifts I will share with my own students. I would also like to thank the members of my dissertation committee for their patience, feedback, and encouragement. I had the opportunity to work with Dr. Barkdull during my first year as his teaching assistant and valued the fact that he was fair, open-minded, and pushed students to think critically. I only had a chance to know Dr. Glen Biglasier for a short time, but appreciated his enthusiasm, kindness, and his suggestions along the way. It was also wonderful to have Ambassador Nagy on my committee and he provided invaluable insights from his experience from living and working in Africa. I want to offer many thanks to Dr. Susan Banducci for her support while she was at Texas Tech and Dr. -

Ben Schoeman Freeway

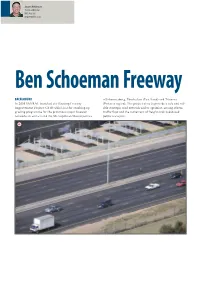

Jurgens Weidemann Technical Director BKS (Pty) Ltd [email protected] Ben Schoeman Freeway BACKGROUND of Johannesburg, Ekurhuleni (East Rand) and Tshwane In 2008 SANRAL launched the Gauteng Freeway (Pretoria region). The project aims to provide a safe and reli- Improvement Project (GFIP) which is a far-reaching up- able strategic road network and to optimise, among others, grading programme for the province’s major freeway traffic flow and the movement of freight and road-based networks in and around the Metropolitan Municipalities public transport. 1 The GFIP is being implemented in phases. The first phase 1 Widened to five lanes per carriageway comprises the improvement of approximately 180 km of 2 Bridge widening at the Jukskei River existing freeways and includes 16 contractual packages. The 3 Placing beams at Le Roux overpass network improvement comprises the adding of lanes and up- 4 Brakfontein interchange – adding a third lane grading of interchanges. Th e upgrading of the Ben Schoeman Freeway (Work Package 2 C of the GFIP) is described in this article. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES Th e upgraded and expanded freeways will signifi cantly re- duce traffi c congestion and unblock access to economic op- portunities and social development projects. Th e GFIP will provide an interconnected freeway system between the City of Johannesburg and the City of Tshwane, this system currently being one of the main arteries within the north-south corridor. One of the most significant aims of this investment for ordinary citizens is the reduction of travel times since many productive hours are wasted as a result of long travel times. -

A1132-Ba2-002-Jpeg.Pdf

- ■ m m m Two-voice plan bristles with contradictions N the first two articles I either individuals or racial be shared with all those non- wrote that United Party groups, and apart from a brief Europeans who have shown that I reference to what was clearly they have the capacity to take speakers often contradict joint responsibility with us for each other and even them meant as safeguards between the future development of selves in their statements on the two White sections and South Afriea.” ("Weekblad,” which was made in the "Ordered 1 7 . 3 . 6 1 . ) COUNTS v> their race federation plan. In the tame speech the Advance” pamphlet issued by OLITICAL parties, more | Those contradictions are no leader of the United Party doubt an indication that the Sir De Villiers Graaff on Oc than most other organisa- S tober 25, 1960, I could find little went on to say: "W e want j P! tions of people, reflect the whole plan was rather hur them (the Africans) to be re W , i riedly conceived and pre or no reference to constitutional , quality of human material safeguards in United Party presented by eight European \ j they embody. In other words maturely horn and that the members, elected by those I good people tend to make for f leaders of the United Party policy. Natives who have shown them- ■ | a good party, indifferent j have not even considered Nevertheless the United selves to be responsible citi people for an indifferent party, ï certain vital aspects of their Party has as its main policy plank, the safeguarding of zens of our country." But ham and bad people for a bad party.