Remembering the White Rose in West Germany, 1943-1993

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mildred Fish Harnack: the Story of a Wisconsin Woman’S Resistance

Teachers’ Guide Mildred Fish Harnack: The Story of A Wisconsin Woman’s Resistance Sunday, August 7 – Sunday, November 27, 2011 Special Thanks to: Jane Bradley Pettit Foundation Greater Milwaukee Foundation Rudolf & Helga Kaden Memorial Fund Funded in part by a grant from the Wisconsin Humanities Council, with funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the State of Wisconsin. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this project do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Introduction Mildred Fish Harnack was born in Milwaukee; attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison; she was the only American woman executed on direct order of Adolf Hitler — do you know her story? The story of Mildred Fish Harnack holds many lessons including: the power of education and the importance of doing what is right despite great peril. ‘The Story of a Wisconsin Woman’s Resistance’ is one we should regard in developing a sense of purpose; there is strength in the knowledge that one individual can make a difference by standing up and taking action in the face of adversity. This exhibit will explore the life and work of Mildred Fish Harnack and the Red Orchestra. The exhibit will allow you to explore Mildred Fish Harnack from an artistic, historic and literary standpoint and will provide your students with a different perspective of this time period. The achievements of those who were in the Red Orchestra resistance organization during World War II have been largely unrecognized; this is an opportunity to celebrate their heroic action. Through Mildred we are able to examine life within Germany under the Nazi regime and gain a better understanding of why someone would risk her life to stand up to injustice. -

The Sophia Sun Newsletter of the Anthroposophical Society in North Carolina

The Sophia Sun Newsletter of the Anthroposophical Society in North Carolina June 2008 Volume I, Number 3 In This Issue: Calendar…………………3 - 4 Study Groups…….…………5 Rev. Dancey Visit……….18 St. John’s …………………...6 K. Morse Visit……..……..18 Archangel Uriel….…………7 News From China….…….20 Branch Meeting…………….8 African Aid………………...23 Conference Review………..9 On Media and Youth……..26 Poem by Eve Olive………..13 Anthroposophy’s White Natalie Tributes…..…….…15 Rose…………………………28 2 From the Editor: I would like to close this letter with a verse, Dear Friends: which was spoken at the John The theme of this June issue of The Sophia Alexandra Conference, which exemplifies Sun is very much aligned with the Mission the Urielic Spirit: of Uriel, the Archangel of Summer, who So long as Thou dost feel the pain admonishes us to awaken our conscience Which I am spared, and to shine the Light of Truth on all things. The Christ unrecognized We begin with our Festival of St. John, Is working in the World. whose guiding spirit was Uriel and whose For weak is still the Spirit personality and Mission John epitomized in While each is only capable of his incarnations as Elijah and as John. suffering Next is an article about the conference Through his own body. “From the Ashes of 9/11: Called to a New Rudolf Steiner Birth of Freedom”. The conference focused on an incident that should have been a The Sophia Sun will be on hiatus during Urielic awakening to conscience and for the summer months. In the meantime, have a many it was, but for our government, it restful summer. -

Sophie Scholl: the Final Days 120 Minutes – Biography/Drama/Crime – 24 February 2005 (Germany)

Friday 26th June 2015 - ĊAK, Birkirkara Sophie Scholl: The Final Days 120 minutes – Biography/Drama/Crime – 24 February 2005 (Germany) A dramatization of the final days of Sophie Scholl, one of the most famous members of the German World War II anti-Nazi resistance movement, The White Rose. Director: Marc Rothemund Writer: Fred Breinersdorfer. Music by: Reinhold Heil & Johnny Klimek Cast: Julia Jentsch ... Sophie Magdalena Scholl Alexander Held ... Robert Mohr Fabian Hinrichs ... Hans Scholl Johanna Gastdorf ... Else Gebel André Hennicke ... Richter Dr. Roland Freisler Anne Clausen ... Traute Lafrenz (voice) Florian Stetter ... Christoph Probst Maximilian Brückner ... Willi Graf Johannes Suhm ... Alexander Schmorell Lilli Jung ... Gisela Schertling Klaus Händl ... Lohner Petra Kelling ... Magdalena Scholl The story The Final Days is the true story of Germany's most famous anti-Nazi heroine brought to life. Sophie Scholl is the fearless activist of the underground student resistance group, The White Rose. Using historical records of her incarceration, the film re-creates the last six days of Sophie Scholl's life: a journey from arrest to interrogation, trial and sentence in 1943 Munich. Unwavering in her convictions and loyalty to her comrades, her cross- examination by the Gestapo quickly escalates into a searing test of wills as Scholl delivers a passionate call to freedom and personal responsibility that is both haunting and timeless. The White Rose The White Rose was a non-violent, intellectual resistance group in Nazi Germany, consisting of students from the University of Munich and their philosophy professor. The group became known for an anonymous leaflet and graffiti campaign, lasting from June 1942 until February 1943, that called for active opposition to dictator Adolf Hitler's regime. -

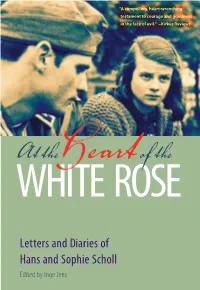

At the Heart of the White Rose: Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie

“A compelling, heart-wrenching testament to courage and goodness in the face of evil.” –Kirkus Reviews AtWHITE the eart ROSEof the Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens This is a preview. Get the entire book here. At the Heart of the White Rose Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens Translated from the German by J. Maxwell Brownjohn Preface by Richard Gilman Plough Publishing House This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com PRINT ISBN: 978-087486-029-0 MOBI ISBN: 978-0-87486-034-4 PDF ISBN: 978-0-87486-035-1 EPUB ISBN: 978-0-87486-030-6 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Contents Foreword vii Preface to the American Edition ix Hans Scholl 1937–1939 1 Sophie Scholl 1937–1939 24 Hans Scholl 1939–1940 46 Sophie Scholl 1939–1940 65 Hans Scholl 1940–1941 104 Sophie Scholl 1940–1941 130 Hans Scholl Summer–Fall 1941 165 Sophie Scholl Fall 1941 185 Hans Scholl Winter 1941–1942 198 Sophie Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 206 Hans Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 213 Sophie Scholl Summer 1942 221 Hans Scholl Russia: 1942 234 Sophie Scholl Autumn 1942 268 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Hans Scholl December 1942 285 Sophie Scholl Winter 1942–1943 291 Hans Scholl Winter 1942–1943 297 Sophie Scholl Winter 1943 301 Hans Scholl February 16 309 Sophie Scholl February 17 311 Acknowledgments 314 Index 317 Notes 325 This is a preview. -

Willi Graf Und Die Weiße Rose: Eine Rezeptionsgeschichte'

H-German Bergen on Blaha, 'Willi Graf und die Weiße Rose: Eine Rezeptionsgeschichte' Review published on Tuesday, August 1, 2006 Tatjana Blaha. Willi Graf und die Weiße Rose: Eine Rezeptionsgeschichte. München: K.G. Saur, 2003. 208 S. EUR 68.00 (gebunden), ISBN 978-3-598-11654-4. Reviewed by Doris L. Bergen (Department of History, University of Notre Dame) Published on H- German (August, 2006) German Resistance Against National Socialism and Its Legacies These three books approach the topic of resistance in National Socialist Germany in different ways, but all raise questions familiar to historians of modern Germany and relevant to anyone concerned with why and how individuals oppose state-sponsored violence. What enabled some people not only to develop a critical stance toward the Nazi regime but to risk their lives to fight against it? How should such heroes be remembered and commemorated? What particular challenges face scholars who try to write the history of resistance? Peter Hoffmann's "family history" of Claus, Count Stauffenberg, is the second edition of his book Stauffenberg (1995), originally published in German in 1992 under the title Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg und seine Brüder. Hoffmann, the dean of studies of the German resistance, uses a traditional biographical approach that locates the roots of Stauffenberg's opposition to National Socialism and his attempt to kill Hitler on July 20, 1944, in his unusual family background, his devotion to the poet Stefan George and the George circle and his experiences in the German military before and during World War II. Informed by decades of research and personal connections with Stauffenberg's family and friends, this book is the product of a mature scholar at the peak of his powers. -

World War II and the Holocaust Research Topics

Name _____________________________________________Date_____________ Teacher____________________________________________ Period___________ Holocaust Research Topics Directions: Select a topic from this list. Circle your top pick and one back up. If there is a topic that you are interested in researching that does not appear here, see your teacher for permission. Events and Places Government Programs and Anschluss Organizations Concentration Camps Anti-Semitism Auschwitz Book burning and censorship Buchenwald Boycott of Jewish Businesses Dachau Final Solution Ghettos Genocide Warsaw Hitler Youth Lodz Kindertransport Krakow Nazi Propaganda Kristalnacht Nazi Racism Olympic Games of 1936 Non-Jewish Victims of the Holocaust -boycott controversy -Jewish athletes Nuremburg Race laws of 1935 -African-American participation SS: Schutzstaffel Operation Valkyrie Books Sudetenland Diary of Anne Frank Voyage of the St. Louis Mein Kampf People The Arts Germans: Terezín (Theresienstadt) Adolf Eichmann Music and the Holocaust Joseph Goebbels Swingjugend (Swing Kids) Heinrich Himmler Claus von Stauffenberg Composers Richard Wagner Symbols Kurt Weill Swastika Yellow Star Please turn over Holocaust Research Topics (continued) Rescue and Resistance: Rescue and Resistance: People Events and Places Dietrich Bonhoeffer Danish Resistance and Evacuation of the Jews Varian Fry Non-Jewish Resistance Miep Gies Jewish Resistance Oskar Schindler Le Chambon (the French town Hans and Sophie Scholl that sheltered Jewish children) Irena Sendler Righteous Gentiles Raoul Wallenburg Warsaw Ghetto and the Survivors: Polish Uprising Viktor Frankl White Rose Elie Wiesel Simon Wiesenthal Research tip - Ask: Who? What? Where? When? Why? How? questions. . -

The White Rose in Cooperation With: Bayerische Landeszentrale Für Politische Bildungsarbeit the White Rose

The White Rose In cooperation with: Bayerische Landeszentrale für Politische Bildungsarbeit The White Rose The Student Resistance against Hitler Munich 1942/43 The Name 'White Rose' The Origin of the White Rose The Activities of the White Rose The Third Reich Young People in the Third Reich A City in the Third Reich Munich – Capital of the Movement Munich – Capital of German Art The University of Munich Orientations Willi Graf Professor Kurt Huber Hans Leipelt Christoph Probst Alexander Schmorell Hans Scholl Sophie Scholl Ulm Senior Year Eugen Grimminger Saarbrücken Group Falk Harnack 'Uncle Emil' Group Service at the Front in Russia The Leaflets of the White Rose NS Justice The Trials against the White Rose Epilogue 1 The Name Weiße Rose (White Rose) "To get back to my pamphlet 'Die Weiße Rose', I would like to answer the question 'Why did I give the leaflet this title and no other?' by explaining the following: The name 'Die Weiße Rose' was cho- sen arbitrarily. I proceeded from the assumption that powerful propaganda has to contain certain phrases which do not necessarily mean anything, which sound good, but which still stand for a programme. I may have chosen the name intuitively since at that time I was directly under the influence of the Span- ish romances 'Rosa Blanca' by Brentano. There is no connection with the 'White Rose' in English history." Hans Scholl, interrogation protocol of the Gestapo, 20.2.1943 The Origin of the White Rose The White Rose originated from individual friend- ships growing into circles of friends. Christoph Probst and Alexander Schmorell had been friends since their school days. -

Historic City Tour: “Saarbrücken in Nazi Germany“

Das Zentrum für internationale Studierende – ZiS – des International Office informiert: UNIVERSITÄT DES SAARLANDES Historic City tour: “Saarbrücken in Nazi Germany“ Overview Despite the damage the Second World War caused to the city centre of Saarbrücken during the 1940s, some places still remind inhabitants and visitors of the time during the reign of the Na- tional Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) and its innumerable victims. The tour through the city will stop at memorial places and locations that were important for the functioning of Hitler’s rule over Germany in general and the Saarland in particular. Its main goal is to show social structures and peoples' behaviour, circumstances and ideologies surrounding the 10 year rule of the Nazi party in the Saarland. Focussing on circumstances which characterised the Saarland before it was re-united with the German Reich, the tour explores the development of the region during and after the Nazi regime. The main focus will lie on nationalist-socialist oppression strategies, propaganda, social policy and the persecuted and murdered victims of the dictatorship. The tour will visit the following places: the old synagogue, the grave of Willi Graf, the police barracks, the Schlossplatz, the Gestapo-Cell in the basement of the Historic Museum and the memorial site „Goldene Bremm“. The guide will also explain the aftermath of World War 2 and the process of coming to terms with and remembering the horrible past. History of the Saarland (1793-1959) Its location on the border between France and Germany has given the Saarland a unique history. After the French Revolution, the former independence of the states in the region of the Saarland was terminated in 1792 and made part of the French Republic. -

An Analysis on the Influence of Christianity on the White Rose

Religion and Resistance: An Analysis on the Influence of Christianity on the White Rose Resistance Movement Laura Kincaide HIST 3120: Nazi German Culture Dr. Janet Ward December 1, 2014 1 Because religion often leads people to do seemingly irrational things, understanding a person’s religion is essential to understand his/her actions. This was especially true in Nazi Germany when religious conviction led some people to risk their lives to do what they believed was right, others allowed their religion to be transformed and co-opted by the Nazis to fit a political agenda while meeting spiritual needs, and still others simply tried to ignore the cognitive dissonance of obeying an authority that was acting in direct contradiction to a spiritual one. This paper will examine the role of Christianity in resistance movements against the Nazis with a focus on the White Rose in an attempt to explain how members of the same religion could have had such drastically different responses to the National Socialists. The White Rose resistance movement officially began in June, 1942 when the group’s first anti-Nazi pamphlet was published and distributed, although the activities and broodings of the members far predated this event. The movement started at the University of Munich, where a small group of students, most notably Hans Scholl, Sophie Scholl, Alex Schmorell, Willi Graf, Christoph Probst, and Traute Lafrenz, and their philosophy and musicology professor, Kurt Huber, discovered that they shared negative opinions of the Nazis and began meeting in secret to discuss their dissident political views.i Some of the most dedicated and passionate members felt the need to spread their ideas throughout the German populace and call upon their fellow citizens to passively resist the Nazis. -

SOPHIE SCHOLL (1921 –1943) and HANS SCHOLL of the White Rose Non-‐Violent &

SOPHIE SCHOLL (1921 –1943) and HANS SCHOLL of the White Rose non-violent resistance group "Human progress is neither automatic nor inevitable. Even a superficial look at history reveals that no social advance rolls in on the wheels of inevitability. Every step toward the goal of justice requires sacrifice, suffering, and struggle: the tireless exertions and passionate concern of dedicated individuals…Life's most persistent and urgent question is 'What are you doing for others?' " "Cowardice asks the question 'Is it safe?' Expediency asks the question 'Is it popular?' But conscience asks the question, 'Is it right?' " --Martin Luther King, Jr. “Braving all powers, Holding your own.” --Goethe “Sometimes I wish I could yell, ‘My name is Sophie Scholl! Remember that!’” Sophie’s sister Inge Aicher-Scholl: For Sophie, religion meant an intensive search for the meaning of her life, and for the meaning and purpose of history….Like any adolescent…you question the child’s faith you grew up with, and you approach issues by reasoning….You discover freedom, but you also discover doubt. That is why many people end up abandoning the search. With a sigh of relief they leave religion behind, and surrender to the ways society says they ought to believe. At this very point, Sophie renewed her reflections and her searching. The way society wanted her to behave had become too suspect…..But what was it life wanted her to do? She sensed that God was very much relevant to her freedom, that in fact he was challenging it. The freedom became more and more meaningful to her. -

German Eyewitness of Nazi-Germany Franz J. Müller Talks to Students And

German eyewitness of Nazi -Germany Franz J. Mü ller talks to students and high school pupils On 2 May students of the German section in the Department of Modern Foreign languages and grade 11 and 12 pupils of German from Paul Roos, Bloemhof and Rhenish had the privilege to meet Mr . Franz J. Mü ller , one of the last surviving members of the White Rose Movement ( “Weiß e Rose” ), a student resistance organisation led by Hans and Sophie Scholl in Munich during the Nazi -era. Mr. Müller, a guest of the Friedrich Ebe rt Stiftung, came to Cape Town to open an exhibition on the White Rose Movement at the Holocaust Centre. Franz Müller was born in 1924 in Ulm where he went to the same High S chool as Sophie and Hans Scholl . Like everyone at the time we was forced to work for the state (“Reichsarbeitsdienst”) and during this time participated in acts of resistance. From 24 to 26 January 1943 he helped to distribute the now famous Leaflet V of the “Wei ße Rose” in Stuttgart . He was arrested two months later in France shortly after having been conscripted to the army. I n the second trial against the W eiße Rose at the Volksgerichtshof (court of the people) he was sentenced by infamous judge Roland Freisler for High Treason to 5 years of imprisonment. Just before the end of the Second World War he was set free by the US Army. As chair of the Weiße Rose Stiftung (The White Rose Foundation) he speaks since 1979 at public discussions in schools, universities and other educational institutions. -

Life in Nazi Germany – Alarming Facts of the Past

Dear reader, This is a historical newspaper made by pupils of the 10 th grade. It´s in English because of the so called “bilingual lessons” which means that we have got some subjects in English. The following articles deal with the main topic “What was life in National Socialism like?” While reading you will see there are many articles on different topics made by different groups. In the index you may choose an article and turn to the page you like to. Please enjoy! Yours, 10bil (may 2008) Life in Nazi Germany – alarming facts of the past INDEX Women and Family in Nazi Germany Amelie 2 Laura 4 Young People in Germany at the time of National Socialism Linda & Marike 6 What happened to cultural life in National Socialism? Hannah & Leonie 9 Propaganda Sophie 13 Workers and work Basile 16 Economy in Nazi Germany Josephin 18 Terror in Nazi Germany Paul 20 Opposition / Resistance Greta & Stefanie Sa. 24 German Army Ian 27 Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP) (National Socialist German Workers’ Party) Marie 31 Fascism Stefanie St. 34 Sources 36 1 Women and Family in Nazi Germany Amelie In Nazi Germany women had to fulfil a specific role as mothers and wives. Instead of working they should stay at home, cook and take care of their children. Many high-skilled women like teachers, lawyers and doctors were dismissed. After 1939 only few women were left in professional jobs. A common rhyme for women was: "Take hold of kettle, broom and pan, Then you’ll surely get a man! Shop and office leave alone, Your true life work lies at home." To encourage married couples to get many children Hitler introduced the “Law for the Encouragement of Marriage”.