Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libertarian Party of Hawaii

Libertarian Party of Hawaii Editor: Roger Taylor Party Chair: Ken Schoolland Vol. 46 Number 2 March, 2010 A Day in the Life? By Ken Schoolland Last month an article appeared in these pages of LPH News called “A Day in the Life of a Republican,” by John Gray. It was an ignorant attempt to mock Republicans and anyone else who challenges the necessity of government in every aspect of our lives. We received feedback from only one person. It was negative and well-deserved. But why only one criticism? Okay, maybe this means that very few of our libertarian audience actually read the LPH News or that they concluded that the local party organization had gone over to the dark side. Well, it was a mistake that the article was printed, but maybe it served a useful purpose by measuring the paltry impact of the LPH News. It is time to change that. I know Hawaii libertarians have a hearty discussion on line, but maybe we can encourage such deliberations in these pages as well. I’ll start by challenging the points raised in that silly essay by John Gray last month. The essay gives the impression that the government is the source of all things good that we take for granted: clean air, water & food, union pay and medical benefits, unemployment and social security insurance, affordable public transport, bank deposit insurance, government education and student loans, and rural electrification. In short, government should be adored! To begin, all countries of the world have governments but few countries enjoy the high standard of living that exists in American. -

Vrijbrief 128/129

MAANDBLAD 128/129 WERKGELEGENHEID oktober/november 1988 Ir H.J. Jongen sr. Voorzitter Stichting Libertarisch Centrum Het is interessant om te bezien hoe er thans over het mini- mumloon wordt gepraat. In het verleden werden wij vaak beticht van hardheid als we verklaarden dat afschaffing van dat minimumloon één van de beste middelen is om de werkgelegenheid te bevorderen. Zelfs al kon men geen speld tussen de redenering krijgen. Swaziland '88 De laatste tijd horen we echter regelmatig dat verlaging van deze loondrempel veel nieuwe arbeidsplaatsen kan scheppen. Het Nederlandse Nationale Planbureau heeft het nu uitgere- kend, en in de recente regeringsverklaring is gesproken over 15% verlaging. Allerlei andere percentages en varianten Freedom torch award worden genoemd. Zo is er bijvoorbeeld door het Nederlands komt naar Europa 5 Christelijk Werkgeversverbond, het NCW, uitgerekend dat deze 15% al een vergroting van de werkgelegenheid met 200.000 banen oplevert en dat er dan f 1.900.000.000 min- der aan uitkeringen hoeft te worden uitbetaald. U kunt begrijpen dat het volledig vrij laten van de afspraken die een werkgever met zijn nieuwe werknemers maakt, een Dus U bent nog veel grotere winst oplevert. Libertariër? 6 Grotere vrijheid geeft meer welvaart. Waarom gebeurt het dan niet onmiddellijk? Ik zie daarvoor twee redenen. Ten eerste is het minimumloon een praktisch middel voor po- litici, (en vakbonden) om aan het volk dat niet doordenkt, Een samenvatting van of niet de capaciteit heeft om het te begrijpen, aan te tonen de tien programmapunten wat zij allemaal gedaan en bereikt hebben. van het Communisme 10 Ten tweede vallen deze informatie op een vruchtbare bodem bij personen die werk HEBBEN. -

Three-Sided Football and the Alternative Soccerscape: a Study of Sporting Space, Play and Activism

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Pollock, Benjin (2021) Three-sided Football and the Alternative Soccerscape: A Study of Sporting Space, Play and Activism. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/86739/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Three-sided Football and the Alternative Soccerscape: A Study of Sporting Space, Play and Activism Abstract: Three teams, three goals, and one ball. Devised as an illustrative example of ‘triolectics’, Danish artist and philosopher Asger Jorn conceived of three-sided football in 1962. However, the game remained a purely abstract philosophical exercise until the early 1990s when a group of anarchists, architects and artists decided to play the game for the first time. -

SPACE, RELIGION, and the CREATURELINESS of APPALACHIA Dissertation Submitted to the College of Arts and Scie

OF MOUNTAIN FLESH: SPACE, RELIGION, AND THE CREATURELINESS OF APPALACHIA Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Scott Cooper McDaniel UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio May 2018 OF MOUNTAIN FLESH: SPACE, RELIGION, AND THE CREATURELINESS OF APPALACHIA Name: McDaniel, Scott Cooper APPROVED BY: ____________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor ____________________________________________ Silviu Bunta, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ____________________________________________ Kelly Johnson, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ____________________________________________ Anthony Smith, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _____________________________________________ Norman Wirzba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _____________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Scott Cooper McDaniel All rights reserved 2018 iii ABSTRACT OF MOUNTAIN FLESH: SPACE, RELIGION, AND THE CREATURELINESS OF APPALACHIA Name: McDaniel, Scott Cooper University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Vincent J. Miller The following dissertation articulates a constructive theology of creatureliness that speaks from within the particularities of Appalachia’s spatial topography and religious culture. I analyze the historical development and ecological implications of industrial resource extraction, specifically the practice of mountaintop removal, within the broader framework of urbanization and anthropocentricism. Drawing on the unique religio-cultural traditions of the region, particularly its 19th century expressions of Christianity, I employ a spatial hermeneutic through which I emphasize the region’s environmental and bodily elements and articulate a theological argument for the “creaturely flesh” of Appalachia. iv Dedicated to Jade and Beatrice v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are numerous individuals that have made this dissertation possible. I would first like to thank Dr. -

An Exploration of Perceptions, Adaptive Capacity and Food Security in The

An exploration of perceptions, adaptive capacity and food security in the Ngqushwa Local Municipality, Eastern Cape, South Africa By Sonwabo Perez Mazinyo Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Geography in the Department of Geography and Environmental Sciences at the University of Fort Hare Supervisors: Prof. Werner Nel and Dr. Leocadia Zhou 2015 DECLARATION I, Sonwabo Perez Mazinyo, hereby declare that: 1) The work in this thesis is my own original work; 2) This thesis has not been previously submitted in full or partial fulfillment of the requirements for an equivalent qualification at any other recognised education institution. NAME: SONWABO PEREZ MAZINYO SIGNATURE: __________________ DATE: 31 August 2015 PLACE: UNIVERSITY OF FORT HARE, ALICE ii ABSTRACT Approximately sixty percent of Africans depend on rainfed agriculture for their livelihoods. South Africa is evidenced to be susceptible to inclement climate which impacts on rural livelihoods as well as on farming systems. While South Africa is considered to be food sufficient, it is estimated that approximately 35% of the population is vulnerable to food insecurity. Therefore with the application of surveys and interviews this study investigates the factors influencing household, subsistence and small-scale farmer perceptions of vulnerability to climate variability as well as the determinants of adaptive capacity. A sample of 308 households is surveyed and four focus group discussions are administered in Ngqushwa Local Municipality as a case study. Furthermore, the study also focuses on the biophysical changes or factors (scientific analysis of the prevailing climatic regimes–rainfall trends); the interrogation of the impact of food systems on both food prices as well as its implications on food sovereignty. -

Bowling Alone, but Online Together? Virtual Communities and American Public Life

Bowling Alone, But Online Together? Virtual Communities and American Public Life Felicia Wu Song Charlottesville, Virginia B.A., Yale University, 1994 M.A., Northwestern University, 1996 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology University of Virginia May, 2005 Bowling Alone, but Online Together? Virtual Communities and American Public Life Felicia Wu Song James Davison Hunter, Chair Department of Sociology University of Virginia ABSTRACT The integration of new communication technologies into the fabric of everyday life has raised important questions about their effects on existing conceptions and practices of community, relationship, and personal identity. How do these technologies mediate and reframe our experience of social interactions and solidarity? What are the cultural and social implications of the structural changes that they introduce? This dissertation critically considers these questions by examining the social and technological phenomenon of online communities and their role in the ongoing debates about the fate of American civil society. In light of growing concerns over declining levels of trust and civic participation expressed by scholars such as Robert Putnam, many point to online communities as possible catalysts for revitalizing communal life and American civic culture. To many, online communities appear to render obsolete not only the barriers of space and time, but also problems of exclusivity and prejudice. Yet others remain skeptical of the Internet's capacity to produce the types of communities necessary for building social capital. After reviewing and critiquing the dominant perspectives on evaluating the democratic efficacy of online communities, this dissertation suggests an alternative approach that draws from the conceptual distinctions made by Mark E. -

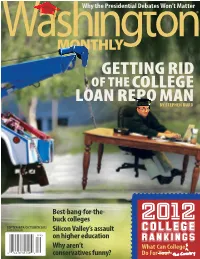

Getting Rid of Thecollege Loan Repo Man by STEPHEN Burd

Why the Presidential Debates Won’t Matter GETTING RID OF THECOLLEGE LOAN REPO MAN BY STEPHEN BURd Best-bang-for-the- buck colleges 2012 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 $5.95 U.S./$6.95 CAN Silicon Valley’s assault COLLEGE on higher education RANKINGS Why aren’t What Can College conservatives funny? Do For You? HBCUsHow do tend UNCF-member to outperform HBCUsexpectations stack in up successfully against other graduating students from disadvantaged backgrounds. higher education institutions in this ranking system? They do very well. In fact, some lead the pack. Serving Students and the Public Good: HBCUs and the Washington Monthly’s College Rankings UNCF “Historically black and single-gender colleges continue to rank Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute Institute for Capacity Building well by our measures, as they have in years past.” —Washington Monthly Serving Students and the Public Good: HBCUs and the Washington “When it comes to moving low-income, first-generation, minority Monthly’s College Rankings students to and through college, HBCUs excel.” • An analysis of HBCU performance —UNCF, Serving Students and the Public Good based on the College Rankings of Washington Monthly • A publication of the UNCF Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute To receive a free copy, e-mail UNCF-WashingtonMonthlyReport@ UNCF.org. MH WashMonthly Ad 8/3/11 4:38 AM Page 1 Define YOURSELF. MOREHOUSE COLLEGE • Named the No. 1 liberal arts college in the nation by Washington Monthly’s 2010 College Guide OFFICE OF ADMISSIONS • Named one of 45 Best Buy Schools for 2011 by 830 WESTVIEW DRIVE, S.W. The Fiske Guide to Colleges ATLANTA, GA 30314 • Named one of the nation’s most grueling colleges in 2010 (404) 681-2800 by The Huffington Post www.morehouse.edu • Named the No. -

Moving Beyond the Corporation: Recovering

MOVING BEYOND THE CORPORATION: RECOVERING AN ONTOLOGY OF PARTICIPATION TO ENVISION NEW FORMS OF BUSINESS Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in Theological Studies By Maura Stephanie Donahue Dayton, Ohio December, 2011 MOVING BEYOND THE CORPORATION: RECOVERING AN ONTOLOGY OF PARTICIPATION TO ENVISION NEW FORMS OF BUSINESS Name: Donahue, Maura Stephanie APPROVED BY: ________________________________________________________________ Kelly S. Johnson, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _______________________________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ______________________________________________________________ D. Stephen Long, Ph.D. Faculty Reader, Marquette University _____________________________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Chairperson ii ABSTRACT MOVING BEYOND THE CORPORATION: RECOVERING AN ONTOLOGY OF PARTICIPATION TO ENVISION NEW FORMS OF BUSINESS Name: Donahue, Maura Stephanie University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Kelly S. Johnson This thesis offers a critique of the publicly traded, for-profit corporate form of business organization in light of the Catholic social tradition. It highlights the ways in which this organizational form is inconsistent with the view of the human person, work, and participation in the economy articulated in Pope John Paul II’s encyclical Laborem Exercens and Pope Benedict XVI’s encyclical Caritas in Veritate. The thesis argues that the corporate -

The Road to Colonialislll in Soiilalia

The Road to Colonialislll February 1993 Vol. 6, No.3 $4.00 in SOIIlalia , D 3 (~Liberty consists in doing what one desires. "-]. S. Mill Volume 2 • IICapitalism Comes to Poland?" by Krzysztof Ostaszewski • IIFear and Loathing in New York City," by Murray N. Rothbard September 1988 Plus articles and reviews by Loren Lomasky, Michael Christian, Richard • IIScrooge McDuck and His Creator," by Phil Salin Kostelanetz, R.W. Bradford and others; and an interview with Russell • IILiberty and Ecology," by John Hospers Means. (72 pages) • liThe Ultimate Justification of the Private Property Ethic," by Hans Hermann Hoppe January 1990 • liThe Greenhouse Effect: Myth or Danger?" by Patrick J. Michaels Plus reviews and articles by Douglas Casey, Murray Rothbard, L. Neil • "The Case for Paleolibertarianism/' by Llewelyn Rockwell Smith and others; and a short story by Erika Holzer. (SO pages)" • "In Defense ofJim Baker and Zsa Zsa," by Ethan O. Waters November 1988 • liThe Death of Socialism: What It Means," by R W. Bradford, Murray • IITaking Over the Roads," by John Semmens Rothbard, Stephen Cox, and William P. Moulton • liThe Search for We The Living," by R.W. Bradford Plus writing by Andrew Roller, David Gordon and others; and an inter • "Private Property: Hope for the Environment," by Jane S. Shaw view with Barbara Branden. (80 pages) Plus articles and reviews by Walter Block, Stephen Cox, John Dentinger, James Robbins and others. (SO pages) March 1990 • liThe Case Against Isolationism," by Stephen Cox January 1989 • "H.L. Mencken: Anti-Semite?" by R W. Bradford • IIAIDS and the FDA," by Sandy Shaw • IIHong Kong Today," by RK. -

Download Something Ready-Made

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Mazzilli-Daechsel, Stefano (2018) Invention and Resistance: FabLabs against Proletarianization. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent, Universität Hamburg. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/71693/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html INVENTION AND RESISTANCE FabLabs Against Proletarianization by Stefano Mazzilli-Daechsel School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research University of Kent Institut für Kriminologische Sozialforschung Universität Hamburg 30 March 2018 68,672 words Thesis submitted to the Universität Hamburg and the University of Kent in partial fulfilment for requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy after following the Erasmus Mundus Doctoral Programme in Cultural and Global Criminology Thesis Supervised by Prof Susanne Krasmann Universität Hamburg Dr Vince Miller University of Kent Dr Phil Carney University of Kent 2 Invention and Resistance: FabLabs Against Proletarianization The contemporary philosopher Bernard Stiegler has reopened the debate on the historically Marxist concept of proletarianization. -

Wikipedia @ 20

Wikipedia @ 20 Wikipedia @ 20 Stories of an Incomplete Revolution Edited by Joseph Reagle and Jackie Koerner The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2020 Massachusetts Institute of Technology This work is subject to a Creative Commons CC BY- NC 4.0 license. Subject to such license, all rights are reserved. The open access edition of this book was made possible by generous funding from Knowledge Unlatched, Northeastern University Communication Studies Department, and Wikimedia Foundation. This book was set in Stone Serif and Stone Sans by Westchester Publishing Ser vices. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Reagle, Joseph, editor. | Koerner, Jackie, editor. Title: Wikipedia @ 20 : stories of an incomplete revolution / edited by Joseph M. Reagle and Jackie Koerner. Other titles: Wikipedia at 20 Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020000804 | ISBN 9780262538176 (paperback) Subjects: LCSH: Wikipedia--History. Classification: LCC AE100 .W54 2020 | DDC 030--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020000804 Contents Preface ix Introduction: Connections 1 Joseph Reagle and Jackie Koerner I Hindsight 1 The Many (Reported) Deaths of Wikipedia 9 Joseph Reagle 2 From Anarchy to Wikiality, Glaring Bias to Good Cop: Press Coverage of Wikipedia’s First Two Decades 21 Omer Benjakob and Stephen Harrison 3 From Utopia to Practice and Back 43 Yochai Benkler 4 An Encyclopedia with Breaking News 55 Brian Keegan 5 Paid with Interest: COI Editing and Its Discontents 71 William Beutler II Connection 6 Wikipedia and Libraries 89 Phoebe Ayers 7 Three Links: Be Bold, Assume Good Faith, and There Are No Firm Rules 107 Rebecca Thorndike- Breeze, Cecelia A. -

Milieus in the Gig Economy Mario Khreiche

Milieus in the Gig Economy Mario Khreiche Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In ASPECT: The Alliance of Social, Political, Ethical, and Cultural Thought Rohan Kalyan, Co-Chair Timothy W. Luke, Co-Chair Daniel Breslau François Debrix Blacksburg, VA Keywords: Gig Economy; Sharing Economy; Platform Economy; On-Demand Economy; Collaborative Economy; The Future of Work; Automation; Interface; Milieu; Motility; Precarity; Liquidation; Potentiality; Inequality; Critical Technology Studies; Political Theory; Econofiction Copyright 2018 Milieus in the Gig Economy Mario Khreiche ACADEMIC ABSTRACT The gig economy (also known as sharing, collaborative, platform, or on-demand economy) has received much attention in recent years for effectively connecting people’s property and resources to booming markets like mobility, tourism, and data processing, among others. In these contexts, proprietary platforms enable users to temporarily make time and material resources available to other users while overseeing respective transactions for a fee. To ensure a careful discussion, the project first provides historical and theoretical context on these developments. Subsequently, the project presents three specific gig economies, namely the ride-hailing service Uber, the home-sharing service Airbnb, and the online labor marketplace Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT). At first glance, the swift and frictionless services in these gig economies suggest an unprecedented level of automation regarding the capacities of smartphones and network technologies. A more detailed inquiry, however, reveals that the ostensible automation in Uber, Airbnb, and AMT unequivocally hinges on the informalization, precarization, and displacement of work. Concretely, labor processes, sociality, and even idle time in these economies are increasingly prearranged, thus shaping behaviors that closely adhere to machine logics and computational protocols.