Nature and Home in the Poetry of Edwardthomas and Robert Frost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zukofsky), 736–37 , 742–43 Asian American Poetry As, 987–88 “ABC” (Justice), 809–11 “Benefi T” Readings, 1137–138 Abolitionism

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00336-1 - The Cambridge History of: American Poetry Edited by Alfred Bendixen and Stephen Burt Index More information Index “A” (Zukofsky), 736–37 , 742–43 Asian American poetry as, 987–88 “ABC” (Justice), 809–11 “benefi t” readings, 1137–138 abolitionism. See also slavery multilingual poetry and, 1133–134 in African American poetry, 293–95 , 324 Adam, Helen, 823–24 in Longfellow’s poetry, 241–42 , 249–52 Adams, Charles Follen, 468 in mid-nineteenth-century poetry, Adams, Charles Frances, 468 290–95 Adams, John, 140 , 148–49 in Whittier’s poetry, 261–67 Adams, L é onie, 645 , 1012–1013 in women’s poetry, 185–86 , 290–95 Adcock, Betty, 811–13 , 814 Abraham Lincoln: An Horatian Ode “Address to James Oglethorpe, An” (Stoddard), 405 (Kirkpatrick), 122–23 Abrams, M. H., 1003–1004 , 1098 “Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley, academic verse Ethiopian Poetess, Who Came literary canon and, 2 from Africa at Eight Year of Age, southern poetry and infl uence of, 795–96 and Soon Became Acquainted with Academy for Negro Youth (Baltimore), the Gospel of Jesus Christ, An” 293–95 (Hammon), 138–39 “Academy in Peril: William Carlos “Adieu to Norman, Bonjour to Joan and Williams Meets the MLA, The” Jean-Paul” (O’Hara), 858–60 (Bernstein), 571–72 Admirable Crichton, The (Barrie), Academy of American Poets, 856–64 , 790–91 1135–136 Admonitions (Spicer), 836–37 Bishop’s fellowship from, 775 Adoff , Arnold, 1118 prize to Moss by, 1032 “Adonais” (Shelley), 88–90 Acadians, poetry about, 37–38 , 241–42 , Adorno, Theodor, 863 , 1042–1043 252–54 , 264–65 Adulateur, The (Warren), 134–35 Accent (television show), 1113–115 Adventure (Bryher), 613–14 “Accountability” (Dunbar), 394 Adventures of Daniel Boone, The (Bryan), Ackerman, Diane, 932–33 157–58 Á coma people, in Spanish epic Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Twain), poetry, 49–50 183–86 Active Anthology (Pound), 679 funeral elegy ridiculed in, 102–04 activist poetry. -

Libertarian Party of Hawaii

Libertarian Party of Hawaii Editor: Roger Taylor Party Chair: Ken Schoolland Vol. 46 Number 2 March, 2010 A Day in the Life? By Ken Schoolland Last month an article appeared in these pages of LPH News called “A Day in the Life of a Republican,” by John Gray. It was an ignorant attempt to mock Republicans and anyone else who challenges the necessity of government in every aspect of our lives. We received feedback from only one person. It was negative and well-deserved. But why only one criticism? Okay, maybe this means that very few of our libertarian audience actually read the LPH News or that they concluded that the local party organization had gone over to the dark side. Well, it was a mistake that the article was printed, but maybe it served a useful purpose by measuring the paltry impact of the LPH News. It is time to change that. I know Hawaii libertarians have a hearty discussion on line, but maybe we can encourage such deliberations in these pages as well. I’ll start by challenging the points raised in that silly essay by John Gray last month. The essay gives the impression that the government is the source of all things good that we take for granted: clean air, water & food, union pay and medical benefits, unemployment and social security insurance, affordable public transport, bank deposit insurance, government education and student loans, and rural electrification. In short, government should be adored! To begin, all countries of the world have governments but few countries enjoy the high standard of living that exists in American. -

Vrijbrief 128/129

MAANDBLAD 128/129 WERKGELEGENHEID oktober/november 1988 Ir H.J. Jongen sr. Voorzitter Stichting Libertarisch Centrum Het is interessant om te bezien hoe er thans over het mini- mumloon wordt gepraat. In het verleden werden wij vaak beticht van hardheid als we verklaarden dat afschaffing van dat minimumloon één van de beste middelen is om de werkgelegenheid te bevorderen. Zelfs al kon men geen speld tussen de redenering krijgen. Swaziland '88 De laatste tijd horen we echter regelmatig dat verlaging van deze loondrempel veel nieuwe arbeidsplaatsen kan scheppen. Het Nederlandse Nationale Planbureau heeft het nu uitgere- kend, en in de recente regeringsverklaring is gesproken over 15% verlaging. Allerlei andere percentages en varianten Freedom torch award worden genoemd. Zo is er bijvoorbeeld door het Nederlands komt naar Europa 5 Christelijk Werkgeversverbond, het NCW, uitgerekend dat deze 15% al een vergroting van de werkgelegenheid met 200.000 banen oplevert en dat er dan f 1.900.000.000 min- der aan uitkeringen hoeft te worden uitbetaald. U kunt begrijpen dat het volledig vrij laten van de afspraken die een werkgever met zijn nieuwe werknemers maakt, een Dus U bent nog veel grotere winst oplevert. Libertariër? 6 Grotere vrijheid geeft meer welvaart. Waarom gebeurt het dan niet onmiddellijk? Ik zie daarvoor twee redenen. Ten eerste is het minimumloon een praktisch middel voor po- litici, (en vakbonden) om aan het volk dat niet doordenkt, Een samenvatting van of niet de capaciteit heeft om het te begrijpen, aan te tonen de tien programmapunten wat zij allemaal gedaan en bereikt hebben. van het Communisme 10 Ten tweede vallen deze informatie op een vruchtbare bodem bij personen die werk HEBBEN. -

Lascelles Abercrombie: a Checklist © Jeff Cooper 1

Lascelles Abercrombie: A Checklist © Jeff Cooper LASCELLES ABERCROMBIE Towards a complete checklist of his published writings Compiled by Jeff Cooper First published in Great Britain in 2004 by White Sheep Press Second edition published on-line in 2013; third edition, 2017 © 2013, 2017 Jeff Cooper All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied or reproduced for publication or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. The rights of Jeff Cooper to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. PREFACE This is the third edition, with additions and amendments (and a renumbering), of the edition originally published in 2004 by White Sheep Press. The intention of this checklist is to list all of the writings published by Abercrombie (although there are almost certainly a large number of book reviews and articles for the Nation that have not been traced). However, without this essential building block, which puts his works into context, meaningful analysis and criticism of his work is difficult. This is a working document, and if you would like to help make it a definitive list, please send any amendments and additions to me at [email protected]. They will be incorporated in the list and acknowledged. The format of the checklist is chronological, in order of first publication in periodical and book form. It should be borne in mind that there is a bibliographical hierarchy: contributions to periodicals, then contributions to books, and finally principal books. -

EDWARD THOMAS: Towards a Complete Checklist of His

Edward Thomas: A Checklist © Jeff Cooper EDWARD THOMAS Towards a Complete Checklist Of His Published Writings Compiled by Jeff Cooper First published in Great Britain in 2004 by White Sheep Press Second edition published on-line in 2013; third edition, 2017 © 2013, 2017 Jeff Cooper All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied or reproduced for publication or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, without the prior permission of the copyright owner and the publishers. The rights of Jeff Cooper to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Preface This is the third edition, with some additions and amendments (and a complete re-numbering), of the edition originally published in 2004 under Richard Emeny’s name, with myself as the editor. The interest in Edward Thomas’s poetry and prose writings has grown considerably over the past few years, and this is an opportune moment to make the whole checklist freely available and accessible. The intention of the list is to provide those with an interest in Thomas with the tools to understand his enormous contribution to criticism as well as poetry. This is very much a work in progress. I can’t say that I have produced a complete or wholly accurate list, and any amendments or additions would be gratefully received by sending them to me at [email protected]. They will be incorporated in the list and acknowledged. -

Three-Sided Football and the Alternative Soccerscape: a Study of Sporting Space, Play and Activism

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Pollock, Benjin (2021) Three-sided Football and the Alternative Soccerscape: A Study of Sporting Space, Play and Activism. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/86739/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Three-sided Football and the Alternative Soccerscape: A Study of Sporting Space, Play and Activism Abstract: Three teams, three goals, and one ball. Devised as an illustrative example of ‘triolectics’, Danish artist and philosopher Asger Jorn conceived of three-sided football in 1962. However, the game remained a purely abstract philosophical exercise until the early 1990s when a group of anarchists, architects and artists decided to play the game for the first time. -

SPACE, RELIGION, and the CREATURELINESS of APPALACHIA Dissertation Submitted to the College of Arts and Scie

OF MOUNTAIN FLESH: SPACE, RELIGION, AND THE CREATURELINESS OF APPALACHIA Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Scott Cooper McDaniel UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio May 2018 OF MOUNTAIN FLESH: SPACE, RELIGION, AND THE CREATURELINESS OF APPALACHIA Name: McDaniel, Scott Cooper APPROVED BY: ____________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor ____________________________________________ Silviu Bunta, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ____________________________________________ Kelly Johnson, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ____________________________________________ Anthony Smith, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _____________________________________________ Norman Wirzba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _____________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Scott Cooper McDaniel All rights reserved 2018 iii ABSTRACT OF MOUNTAIN FLESH: SPACE, RELIGION, AND THE CREATURELINESS OF APPALACHIA Name: McDaniel, Scott Cooper University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Vincent J. Miller The following dissertation articulates a constructive theology of creatureliness that speaks from within the particularities of Appalachia’s spatial topography and religious culture. I analyze the historical development and ecological implications of industrial resource extraction, specifically the practice of mountaintop removal, within the broader framework of urbanization and anthropocentricism. Drawing on the unique religio-cultural traditions of the region, particularly its 19th century expressions of Christianity, I employ a spatial hermeneutic through which I emphasize the region’s environmental and bodily elements and articulate a theological argument for the “creaturely flesh” of Appalachia. iv Dedicated to Jade and Beatrice v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are numerous individuals that have made this dissertation possible. I would first like to thank Dr. -

A Note on the Origins of 1914-18 'War Poetry'

A note on the origins of 1914-18 ‘war poetry’ Dominic Hibberd Biography Dominic Hibberd, was a biographer, editor and critic who taught at universities in Britain, the USA, and China. He wrote biographies of two poets, Harold Monro and Wilfred Owen, as well as the critical study Owen the Poet (1986). He edited Poetry of the First World War in the Casebook series (1981), and with John Onions, compiled and edited The Winter of the World: Poems of the First World War (2007). Abstract The sort of work that has often been thought of as typical British First World War poetry – realistic, often angry poems about the actualities of the front line, written from the point of view of the ordinary soldier and aimed at the civilian conscience – was in fact not typical at all. And it was not begun by soldiers in the aftermath of front-line horrors, as is often supposed, but by two civilian poets very early in the war. Harold Monro and Wilfrid Gibson deserve to be recognised as the first of what modern readers would call the ‘war poets’. Résumé Les œuvres qui sont souvent considérées comme tout à fait caractéristiques de la poésie britannique de la première guerre mondiale, — réalistes, souvent des poèmes d’un style cru, traduisant la réalité du front, telle qu’elle est vécue par le soldat de base, pour en faire prendre conscience aux civils, ne sont en réalité en rien conformes à ce modèle. Les premières œuvres relevant de ce genre n’ont pas été le fait de militaires revenant de l’horreur du front, comme on le croit souvent, mais de deux poètes civils qui les ont écrites au tout début de la guerre. -

An Exploration of Perceptions, Adaptive Capacity and Food Security in The

An exploration of perceptions, adaptive capacity and food security in the Ngqushwa Local Municipality, Eastern Cape, South Africa By Sonwabo Perez Mazinyo Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Geography in the Department of Geography and Environmental Sciences at the University of Fort Hare Supervisors: Prof. Werner Nel and Dr. Leocadia Zhou 2015 DECLARATION I, Sonwabo Perez Mazinyo, hereby declare that: 1) The work in this thesis is my own original work; 2) This thesis has not been previously submitted in full or partial fulfillment of the requirements for an equivalent qualification at any other recognised education institution. NAME: SONWABO PEREZ MAZINYO SIGNATURE: __________________ DATE: 31 August 2015 PLACE: UNIVERSITY OF FORT HARE, ALICE ii ABSTRACT Approximately sixty percent of Africans depend on rainfed agriculture for their livelihoods. South Africa is evidenced to be susceptible to inclement climate which impacts on rural livelihoods as well as on farming systems. While South Africa is considered to be food sufficient, it is estimated that approximately 35% of the population is vulnerable to food insecurity. Therefore with the application of surveys and interviews this study investigates the factors influencing household, subsistence and small-scale farmer perceptions of vulnerability to climate variability as well as the determinants of adaptive capacity. A sample of 308 households is surveyed and four focus group discussions are administered in Ngqushwa Local Municipality as a case study. Furthermore, the study also focuses on the biophysical changes or factors (scientific analysis of the prevailing climatic regimes–rainfall trends); the interrogation of the impact of food systems on both food prices as well as its implications on food sovereignty. -

Bowling Alone, but Online Together? Virtual Communities and American Public Life

Bowling Alone, But Online Together? Virtual Communities and American Public Life Felicia Wu Song Charlottesville, Virginia B.A., Yale University, 1994 M.A., Northwestern University, 1996 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology University of Virginia May, 2005 Bowling Alone, but Online Together? Virtual Communities and American Public Life Felicia Wu Song James Davison Hunter, Chair Department of Sociology University of Virginia ABSTRACT The integration of new communication technologies into the fabric of everyday life has raised important questions about their effects on existing conceptions and practices of community, relationship, and personal identity. How do these technologies mediate and reframe our experience of social interactions and solidarity? What are the cultural and social implications of the structural changes that they introduce? This dissertation critically considers these questions by examining the social and technological phenomenon of online communities and their role in the ongoing debates about the fate of American civil society. In light of growing concerns over declining levels of trust and civic participation expressed by scholars such as Robert Putnam, many point to online communities as possible catalysts for revitalizing communal life and American civic culture. To many, online communities appear to render obsolete not only the barriers of space and time, but also problems of exclusivity and prejudice. Yet others remain skeptical of the Internet's capacity to produce the types of communities necessary for building social capital. After reviewing and critiquing the dominant perspectives on evaluating the democratic efficacy of online communities, this dissertation suggests an alternative approach that draws from the conceptual distinctions made by Mark E. -

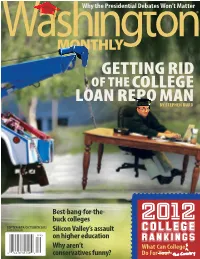

Getting Rid of Thecollege Loan Repo Man by STEPHEN Burd

Why the Presidential Debates Won’t Matter GETTING RID OF THECOLLEGE LOAN REPO MAN BY STEPHEN BURd Best-bang-for-the- buck colleges 2012 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 $5.95 U.S./$6.95 CAN Silicon Valley’s assault COLLEGE on higher education RANKINGS Why aren’t What Can College conservatives funny? Do For You? HBCUsHow do tend UNCF-member to outperform HBCUsexpectations stack in up successfully against other graduating students from disadvantaged backgrounds. higher education institutions in this ranking system? They do very well. In fact, some lead the pack. Serving Students and the Public Good: HBCUs and the Washington Monthly’s College Rankings UNCF “Historically black and single-gender colleges continue to rank Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute Institute for Capacity Building well by our measures, as they have in years past.” —Washington Monthly Serving Students and the Public Good: HBCUs and the Washington “When it comes to moving low-income, first-generation, minority Monthly’s College Rankings students to and through college, HBCUs excel.” • An analysis of HBCU performance —UNCF, Serving Students and the Public Good based on the College Rankings of Washington Monthly • A publication of the UNCF Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute To receive a free copy, e-mail UNCF-WashingtonMonthlyReport@ UNCF.org. MH WashMonthly Ad 8/3/11 4:38 AM Page 1 Define YOURSELF. MOREHOUSE COLLEGE • Named the No. 1 liberal arts college in the nation by Washington Monthly’s 2010 College Guide OFFICE OF ADMISSIONS • Named one of 45 Best Buy Schools for 2011 by 830 WESTVIEW DRIVE, S.W. The Fiske Guide to Colleges ATLANTA, GA 30314 • Named one of the nation’s most grueling colleges in 2010 (404) 681-2800 by The Huffington Post www.morehouse.edu • Named the No. -

Moving Beyond the Corporation: Recovering

MOVING BEYOND THE CORPORATION: RECOVERING AN ONTOLOGY OF PARTICIPATION TO ENVISION NEW FORMS OF BUSINESS Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in Theological Studies By Maura Stephanie Donahue Dayton, Ohio December, 2011 MOVING BEYOND THE CORPORATION: RECOVERING AN ONTOLOGY OF PARTICIPATION TO ENVISION NEW FORMS OF BUSINESS Name: Donahue, Maura Stephanie APPROVED BY: ________________________________________________________________ Kelly S. Johnson, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _______________________________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ______________________________________________________________ D. Stephen Long, Ph.D. Faculty Reader, Marquette University _____________________________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Chairperson ii ABSTRACT MOVING BEYOND THE CORPORATION: RECOVERING AN ONTOLOGY OF PARTICIPATION TO ENVISION NEW FORMS OF BUSINESS Name: Donahue, Maura Stephanie University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Kelly S. Johnson This thesis offers a critique of the publicly traded, for-profit corporate form of business organization in light of the Catholic social tradition. It highlights the ways in which this organizational form is inconsistent with the view of the human person, work, and participation in the economy articulated in Pope John Paul II’s encyclical Laborem Exercens and Pope Benedict XVI’s encyclical Caritas in Veritate. The thesis argues that the corporate