The Phrygian Vanak-, the Priest-King, the 'Wanax To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

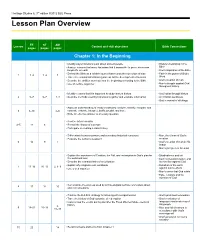

Heritage Studies 6, 3Rd Ed. Lesson Plan Overview

Heritage Studies 6, 3rd edition ©2012 BJU Press Lesson Plan Overview TE ST AM Lesson Content and skill objectives Bible Connections pages pages pages Chapter 1: In the Beginning • Identify ways historians learn about ancient people • History’s beginning in the • Analyze reasons that many historians find it impossible to prove when man Bible began life on earth • God’s inspiration of the Bible • Defend the Bible as a reliable source that records the true origin of man • Faith in the power of God’s 1 1–4 1–4 1 • Trace the evolutionist’s thinking process for the development of humans Word • Describe the abilities man had from the beginning according to the Bible • God’s creation of man • Use an outline organizer • Man’s struggle against God throughout history • Identify reasons that it is important to study ancient history • God’s plan through history 2 5–7 5–7 1, 3 • Describe methods used by historians to gather and evaluate information • A Christian worldview • God in control of all things • Apply an understanding of essay vocabulary: analyze, classify, compare and contrast, evaluate, interpret, justify, predict, and trace 3 8–10 4–6 • Write an effective answer to an essay question • Practice interview skills 4–5 11 8 • Record the history of a person • Participate in creating a class history • Differentiate between primary and secondary historical resources • Man, the climax of God’s • Evaluate the author’s viewpoint creation 6 12 9 7 • God’s creation of man in His image • Man’s job given at Creation • Explain the importance of Creation, the Fall, and redemption in God’s plan for • Disobedience and sin the world and man • Each civilization’s failure and • Describe the characteristics of a civilization its rebellion against God • Explain why religions exist worldwide • Rebellion of the earth 7 13–16 10–13 2, 8–9 • Use a web organizer against man’s efforts • Man’s sense that God exists • False religions and the rejection of God • Demonstrate the process used by archaeologists to draw conclusions about 8 17 14 10 ancient civilizations • Practice the E.A.R.S. -

Disfigured History: How the College Board Demolishes the Past

Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past A report by the Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton 420 Madison Avenue, 7th Floor Published November, 2020. New York, NY 10017 © 2020 National Association of Scholars Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past Report by David Randall Director of Research, National Assocation of Scholars Introduction by Peter W. Wood President, National Association of Scholars Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton Published November, 2020. © 2020 National Association of Scholars About the National Association of Scholars Mission The National Association of Scholars is an independent membership association of academics and others working to sustain the tradition of reasoned scholarship and civil debate in America’s colleges and universities. We uphold the standards of a liberal arts education that fosters intellectual freedom, searches for the truth, and promotes virtuous citizenship. What We Do We publish a quarterly journal, Academic Questions, which examines the intellectual controversies and the institutional challenges of contemporary higher education. We publish studies of current higher education policy and practice with the aim of drawing attention to weaknesses and stimulating improvements. Our website presents educated opinion and commentary on higher education, and archives our research reports for public access. NAS engages in public advocacy to pass legislation to advance the cause of higher education reform. We file friend-of-the-court briefs in legal cases defending freedom of speech and conscience and the civil rights of educators and students. We give testimony before congressional and legislative committees and engage public support for worthy reforms. -

Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION the Maya Empire, Centered in The

Unit III – Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION The Maya Empire, centered in the tropical lowlands of what is now Guatemala, reached the peak of its power and influence around the sixth century A.D. The Maya excelled at agriculture, pottery, hieroglyph writing, calendar-making and mathematics. The Maya civilization was one of the most dominant indigenous societies of Mesoamerica. The earliest Maya settlements date to around 1800 B.C., or the beginning of what is called the Preclassic or Formative Period. The earliest Maya were agricultural, growing crops such as corn (maize), beans, squash and cassava (manioc). During the Middle Preclassic Period, which lasted until about 300 B.C., Maya farmers began to expand their presence both in the highland and lowland regions. The Middle Preclassic Period also saw the rise of the first major Mesoamerican civilization, the Olmecs. Like other Mesamerican peoples, the Maya derived a number of religious and cultural traits. The Maya were deeply religious, and worshiped various gods related to nature, including the gods of the sun, the moon, rain and corn. At the top of Maya society were the kings, or (holy lords), who claimed to be related to gods and followed a hereditary succession. They were thought to serve as mediators between the gods and people on earth, and performed the elaborate religious ceremonies and rituals so important to the Maya culture. Maya Arts and Culture :- The Classic Maya built many of their temples and palaces in a stepped pyramid shape, decorating them with elaborate reliefs and inscriptions. These structures have earned the Maya their reputation as the great artists of ` Mesoamerica. -

KHAZAR UNIVERSITY Faculty

KHAZAR UNIVERSITY Faculty: School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department: English Language and Literature Specialty: English Language and Literature MA THESIS Theme: Historical English Borrowings Master Student: Aynura Huseynova Supervisor: Eldar Shahgaldiyev, Ph.D. January -2014 1 Contents Introduction…………………………………………………....3 – 9 Chapter I: Survey of the English language. Word Stock……………… 10-16 To which group does English language belong? …………… 16-23 Historical Background…………..………………................... 23-27 The historical periods of English language…………………. 27-31 Chapter II: English Borrowings and Their Structural Analysis. The History of English Language (Historical Approach)…… 32-68 Chapter III: Tendency of Future Development of English Borrowings……………………………................... 69-72 Conclusion…………………………………………............ 73-74 References………………………………………………… 75-76 2 INTRODUCTION Although at the end of the every century, learning Latin, Greek, Arabic, Spanish, German, French language spread while replacing each other. But for two centuries the English language got non-substitutive, unchanged status as the world's international language and learning of this language began to spread in our republic widely. The cause of widely spread of the English language all over the not only being the powerful maritime empire Great Britain‘s global colonization policy, but also was easy to master language. It is known that among world languages English has rich vocabulary reserve. The changes in nation's economic-political and cultural life, new production methods, new scientific achievements and technological progress, main turn in agriculture, changes in social structure, science, culture, trade, the development of literature, the creation of the state, and etc., such events were the cause of further enrichment and affect the structure of the dictionary of the English language. -

Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

Václav Blažek (Masaryk University of Brno, Czech Republic) On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: Survey The purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo-European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non-Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian 0.3. Vladimir Georgiev (1981, 363) included in his Indo-European classification some of the relic languages, plus the languages with a doubtful IE affiliation at all: Tocharian Northern Balto-Slavic Germanic Celtic Ligurian Italic & Venetic Western Illyrian Messapic Siculian Greek & Macedonian Indo-European Central Phrygian Armenian Daco-Mysian & Albanian Eastern Indo-Iranian Thracian Southern = Aegean Pelasgian Palaic Southeast = Hittite; Lydian; Etruscan-Rhaetic; Elymian = Anatolian Luwian; Lycian; Carian; Eteocretan 0.4. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Vassilis Lambropoulos C. P. Cavafy Professor of Modern Greek Professor of Classical Studies and Comparative Literature University of Michigan I. PERSONAL Born 1953, Athens, Greece II. EDUCATION University of Athens (Greece), Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 1971-75 (B.A. 1975) University of Thessaloniki (Greece), Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 1976- 79 (Ph.D. 1980) Dissertation Topic: The Poetics of Roman Jakobson Dissertation Title: “Roman Jakobson's Theory of Parallelism” University of Birmingham (England), School of Hellenic and Roman Studies and Department of English, 1979-81, Postdoctoral Fellow III. PROFESSIONAL HISTORY The Ohio State University, Dept. of Near Eastern, Judaic, and Hellenic Languages and Literatures (1981-96) and Dept. of Greek and Latin, Modern Greek Program (1996-99): Assistant (1981-87), Associate (1987-92), and Professor (1992-99) of Modern Greek Dept. of Comparative Studies: Associate Faculty (1989-99) Dept. of History: Associate Faculty (1997-99) University of Michigan, Departments of Classical Studies and Comparative Literature (1999-): C. P. Cavafy Professor of Modern Greek Lambropoulos CV 2 2 IV. FELLOWSHIPS, HONORS and AWARDS Greek Ministry of Culture, Undergraduate Scholarship, University of Athens (Greece), 1971-72 Greek National Scholarship Foundation, Postdoctoral Fellowship, University of Birmingham (England), 1979-81 National Endowment for the Humanities Scholarship for participation in NEH Summer Seminar for College Teachers, "Greek Concepts of Myth and Contemporary Theory," directed by Gregory Nagy, Harvard University, July-August 1985 National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship for University Teachers, 1992-93 Ohio State University Distinguished Scholar Award (one of six campus-wide annual awards), 1994 LSA/OVPR Michigan Humanities Award (one of ten College-wide annual one-semester fellowships), 2005 Outstanding Professor of the Year Award, Office of Greek Life, University of Michigan, April 2005 The Stavros S. -

Ancient Civilisation’ Through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures

Structuring The Notion of ‘Ancient Civilisation’ through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez Institute of Archaeology U C L Thesis forPh.D. in Archaeology 2011 1 I, Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis Signature 2 This thesis is dedicated to my grandparents Emma and Andrés, Dolores and Concepción: their love has borne fruit Esta tesis está dedicada a mis abuelos Emma y Andrés, Dolores y Concepción: su amor ha dado fruto Al ‘Pipila’ porque él supo lo que es cargar lápidas To ‘Pipila’ since he knew the burden of carrying big stones 3 ABSTRACT This research focuses on studying the representation of the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ in displays produced in Britain and the United States during the early to mid-nineteenth century, a period that some consider the beginning of scientific archaeology. The study is based on new theoretical ground, the Semantic Structural Model, which proposes that the function of an exhibition is the loading and unloading of an intelligible ‘system of ideas’, a process that allows the transaction of complex notions between the producer of the exhibit and its viewers. Based on semantic research, this investigation seeks to evaluate how the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ was structured, articulated and transmitted through exhibition practices. To fulfil this aim, I first examine the way in which ideas about ‘ancientness’ and ‘cultural complexity’ were formulated in Western literature before the last third of the 1800s. -

Vowel Change in English and German: a Comparative Analysis

Vowel change in English and German: a comparative analysis Miriam Calvo Fernández Degree in English Studies Academic Year: 2017/2018 Supervisor: Reinhard Bruno Stempel Department of English and German Philology and Translation Abstract English and German descend from the same parent language: West-Germanic, from which other languages, such as Dutch, Afrikaans, Flemish, or Frisian come as well. These would, therefore, be called “sister” languages, since they share a number of features in syntax, morphology or phonology, among others. The history of English and German as sister languages dates back to the Late antiquity, when they were dialects of a Proto-West-Germanic language. After their split, more than 1,400 years ago, they developed their own language systems, which were almost identical at their earlier stages. However, this is not the case anymore, as can be seen in their current vowel systems: the German vowel system is composed of 23 monophthongs and 8 diphthongs, while that of English has only 12 monophthongs and 8 diphthongs. The present paper analyses how the English and German vowels have gradually changed over time in an attempt to understand the differences and similarities found in their current vowel systems. In order to do so, I explain in detail the previous stages through which both English and German went, giving special attention to the vowel changes from a phonological perspective. Not only do I describe such processes, but I also contrast the paths both languages took, which is key to understand all the differences and similarities present in modern English and German. The analysis shows that one of the main reasons for the differences between modern German and English is to be found in all the languages English has come into contact with in the course of its history, which have exerted a significant influence on its vowel system, making it simpler than that of German. -

Chapter Four—Divinity

OUTLINE OF CHAPTER FOUR The Ritual-Architectural Commemoration of Divinity: Contentious Academic Theories but Consentient Supernaturalist Conceptions (Priority II-A).............................................................485 • The Driving Questions: Characteristically Mesoamerican and/or Uniquely Oaxacan Ideas about Supernatural Entities and Life Forces…………..…………...........…….487 • A Two-Block Agenda: The History of Ideas about, then the Ritual-Architectural Expression of, Ancient Zapotec Conceptions of Divinity……………………......….....……...489 I. The History of Ideas about Ancient Zapotec Conceptions of Divinity: Phenomenological versus Social Scientific Approaches to Other Peoples’ God(s)………………....……………495 A. Competing and Complementary Conceptions of Ancient Zapotec Religion: Many Gods, One God and/or No Gods……………………………….....……………500 1. Ancient Oaxacan Polytheism: Greco-Roman Analogies and the Prevailing Presumption of a Pantheon of Personal Gods..................................505 a. Conventional (and Qualified) Views of Polytheism as Belief in Many Gods: Aztec Deities Extrapolated to Oaxaca………..….......506 b. Oaxacan Polytheism Reimagined as “Multiple Experiences of the Sacred”: Ethnographer Miguel Bartolomé’s Contribution……...........514 2. Ancient Oaxacan Monotheism, Monolatry and/or Monistic-Pantheism: Diverse Arguments for Belief in a Supreme Being or Principle……….....…..517 a. Christianity-Derived Pre-Columbian Monotheism: Faith-Based Posits of Quetzalcoatl as Saint Thomas, Apostle of Jesus………........518 b. “Primitive Monotheism,” -

The Christianization of the Nahua and Totonac in the Sierra Norte De

Contents Illustrations ix Foreword by Alfredo López Austin xvii Acknowledgments xxvii Chapter 1. Converting the Indians in Sixteenth- Century Central Mexico to Christianity 1 Arrival of the Franciscan Missionaries 5 Conversion and the Theory of “Cultural Fatigue” 18 Chapter 2. From Spiritual Conquest to Parish Administration in Colonial Central Mexico 25 Partial Survival of the Ancient Calendar 31 Life in the Indian Parishes of Colonial Central Mexico 32 Chapter 3. A Trilingual, Traditionalist Indigenous Area in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 37 Regional History 40 Three Languages with a Shared Totonac Substratum 48 v Contents Chapter 4. Introduction of Christianity in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 53 Chapter 5. Local Religious Crises in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries 63 Andrés Mixcoatl 63 Juan, Cacique of Matlatlán 67 Miguel del Águila, Cacique of Xicotepec 70 Pagan Festivals in Tutotepec 71 Gregorio Juan 74 Chapter 6. The Tutotepec Otomí Rebellion, 1766–1769 81 The Facts 81 Discussion and Interpretation 98 Chapter 7. Contemporary Traditions in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 129 Worship of Tutelary Mountains 130 Shrines and Sacred Constructions 135 Chapter 8. Sacred Drums, Teponaztli, and Idols from the Sierra Norte de Puebla 147 The Huehuetl, or Vertical Drum 147 The Teponaztli, or Female Drum 154 Ancient and Recent Idols in Shrines 173 Chapter 9. Traditional Indigenous Festivities in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 179 The Ancient Festival of San Juan Techachalco at Xicotepec 179 The Annual Festivity of the Tepetzintla Totonacs 185 Memories of Annual Festivities in Other Villages 198 Conclusions 203 Chapter 10. Elements and Accessories of Traditional Native Ceremonies 213 Oblations and Accompanying Rites 213 Prayers, Singing, Music, and Dancing 217 Ritual Idols and Figurines 220 Other Ritual Accessories 225 Chapter 11. -

Religious Studies (RELS) 1

Religious Studies (RELS) 1 RELS 013 Gods, Ghosts, and Monsters RELIGIOUS STUDIES (RELS) This course seeks to be a broad introduction. It introduces students to the diversity of doctrines held and practices performed, and art RELS 002 Religions of the West produced about "the fantastic" from earliest times to the present. The This course surveys the intertwined histories of Judaism, Christianity, fantastic (the uncanny or supernatural) is a fundamental category in and Islam. We will focus on the shared stories which connect these three the scholarly study of religion, art, anthropology, and literature. This traditions, and the ways in which communities distinguished themselves course fill focus both theoretical approaches to studying supernatural in such shared spaces. We will mostly survey literature, but will also beings from a Religious Studies perspective while drawing examples address material culture and ritual practice, to seek answers to the from Buddhist, Shinto, Christian, Hindu, Jain, Zoroastrian, Egyptian, following questions: How do myths emerge? What do stories do? What Central Asian, Native American, and Afro-Caribbean sources from is the relationship between religion and myth-making? What is scripture, earliest examples to the present including mural, image, manuscript, and what is its function in creating religious communities? How do film, codex, and even comic books. It will also introduce students to communities remember and forget the past? Through which lenses and related humanistic categories of study: material and visual culture, with which tools do we define "the West"? theodicy, cosmology, shamanism, transcendentalism, soteriology, For BA Students: History and Tradition Sector eschatology, phantasmagoria, spiritualism, mysticism, theophany, and Taught by: Durmaz the historical power of rumor. -

GREEKS and PRE-GREEKS: Aegean Prehistory and Greek

GREEKS AND PRE-GREEKS By systematically confronting Greek tradition of the Heroic Age with the evidence of both linguistics and archaeology, Margalit Finkelberg proposes a multi-disciplinary assessment of the ethnic, linguistic and cultural situation in Greece in the second millennium BC. The main thesis of this book is that the Greeks started their history as a multi-ethnic population group consisting of both Greek- speaking newcomers and the indigenous population of the land, and that the body of ‘Hellenes’ as known to us from the historic period was a deliberate self-creation. The book addresses such issues as the structure of heroic genealogy, the linguistic and cultural identity of the indigenous population of Greece, the patterns of marriage be- tween heterogeneous groups as they emerge in literary and historical sources, the dialect map of Bronze Age Greece, the factors respon- sible for the collapse of the Mycenaean civilisation and, finally, the construction of the myth of the Trojan War. margalit finkelberg is Professor of Classics at Tel Aviv University. Her previous publications include The Birth of Literary Fiction in Ancient Greece (1998). GREEKS AND PRE-GREEKS Aegean Prehistory and Greek Heroic Tradition MARGALIT FINKELBERG cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521852166 © Margalit Finkelberg 2005 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press.