A Thesis Submitted to the Superior College, Lahore in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMSATS Institute of Information Technology (Virtual Campus) List of Exam Centers

COMSATS Institute of Information Technology (Virtual Campus) List of Exam Centers Center Code Study Center CITY Exam Center Imperial Institute of technology 12-Begum ctisb001 Islamabad Sarfaraz Iqbal Road G-6/4, Islamabad GREEN 20-EAST, Eastern Half, Ghousia Plaza, Quid- ctisb002 e-AzamAvenue/Jinah Avanue, Blue Area, Islamabad Islamabad ASIAN College Iftikhar Avenue Shahpur Bharkahu ctisb003 Islamabad Islamabad Nicon Group of Colleges F-10 campus House no. ctisb004 317, St. no. 58, near flower market F-10/3 Islamabad Islamabad IUSE Schools of Engineering & Managment Science, Malikabad Silver Oak Institute of MIT, (SIMSIT) Address: Plot ctisb006 Islamabad Complex, Murree Road (Near 6th # 12, IEP Building Mauve Area, G-8/1 Islamabad Road), Rawalpindi University College of Advance Technologies ( pbrwp001 UCAT ) 7 B The Mall Opposite State Life Building , Rawalpindi Rawalpindi Nicon Group of Colleges 6th road campus 1st floor pbrwp003 dubai plaza, 6th road crossing Murree road Rawalpindi Rawalpindi SKANS SCHOOL OF ACCOUNTANCY RAWALPINDI pbrwp005 16 , Raja Akram Road, opposite Race Course Rawalpindi Ground, Saddar Rawalpindi Oxford College of Information Technology 1st and pbatk001 2nd floors, Mureed plaza, G.T Road, kamra Cantt, Attock District Attock Govt Post Graduate college for boys pbatk002 Government Post Graduate College Attock Attock (New Hall), Attock pbatk003 OXFORD College of Virtual Education Attock Attock Royal Institute of IT Royal Institute of IT Bhoun pbchk001 Chakwal Road Chakwal Ideal College of Education, Opposite pbchk002 -

Sports Directory for Public and Private Universities Public Sector Universities Federal

Sports Directory for Public and Private Universities Public Sector Universities Federal: 1. Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad Name of Sports Officer: there is no sports officer in said university as per information received from university. Designation: Office Phone No: Celll No: E-mail: Mailing Address: 2. Bahria University, Islamabad Name of Sports Officer: Malik Bashir Ahmad Designation: Dy. Director Sports Office Phone No: 051-9261279 Cell No: 0331-2221333 E-mail: [email protected] Mailing Address: Bahria University, Naval Complex, E-8, Shangrila Road, Islamabad Name of Sports Officer: Mirza Tasleem Designation: Sports Officer Office Phone No: 051-9261279 Cell No: E-mail: [email protected] Mailing Address: as above 3. International Islamic University, Islamabad Name of Sports Officer: Muhammad Khalid Chaudhry Designation: Sports Officer Office Phone No: 051-9019656 Cell No: 0333-5120533 E-mail: [email protected] Mailing Address: Sports Officer, IIUI, H-12, Islamabad 4. National University of Modern Languages (NUML), Islamabad Name of Sports Officer: No Sports Officer Designation: Office Phone No: 051-9257646 Cell No: E-mail: Mailing Address: Sector H-9, Islamabad Name of Sports Officer: Saeed Ahmed Designation: Demonstrator Office Phone No: 051-9257646 Cell No: 0335-5794434 E-mail: [email protected] Mailing Address: as above 5. Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad Name of Sports Officer: M. Safdar Ali Designation: Dy. Director Sports Office Phone No: 051-90642173 Cell No: 0333-6359863 E-mail: [email protected] Mailing Address: Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad 6. National University of Sciences and Technology, Islamabad Name of Sports Officer: Mrs. -

Punjab Government Rules of Business 20111

Page 1 of 121 GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB SERVICES AND GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT (CABINET WING) Dated Lahore the 11th March, 2011 NOTIFICATION No.SO(Cab-I)2-3/2011.– In exercise of the powers conferred under Article 139 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Government of the Punjab is pleased to make the following Rules: PART-A GENERAL 1. Short title and commencement.– (1) These rules may be cited as the Punjab Government Rules of Business 20111. (2) They shall come into force at once. 2. Definitions.– In these rules, unless the context otherwise requires: (a) “Assembly” means the Provincial Assembly of the Punjab; (b) “Attached Department” means a department mentioned in column 3 of the First Schedule; (c) “Autonomous Body” means a Body mentioned in column 4 of the First Schedule; (d) “Business” means the work done by the Government; (e) “Cabinet” means the Cabinet of Ministers, with the Chief Minister at its head as mentioned in Article 130 of the Constitution; (f) “Case” means a particular matter under consideration and includes all papers pertaining to it and necessary for its disposal, such as correspondence and notes and any previous papers connected with the subject; (g) “Chief Secretary” means the officer notified as such in the Gazette, and includes Additional Chief Secretary in Services and General Administration Department; 2[(ga) “Commissioner”, “Additional Commissioner”, “Deputy Commissioner”, “Additional Deputy Commissioner” and “Assistant Commissioner” shall have the same meanings as are respectively assigned to them in the Punjab Civil Administration Act 2017 (III of 2017);] 1Approved by the Provincial Cabinet in its meeting held on March 08, 2011 in terms of Article 139 of the Constitution of the Islamic republic of Pakistan. -

PROF. DR. MUQQADAS REHMAN Phone: +924299231257 Fax: +924299231259 E-Mail: [email protected]

PROF. DR. MUQQADAS REHMAN Phone: +924299231257 Fax: +924299231259 E-mail: [email protected] QUALIFICATION 2014 Doctor of Philosophy (Marketing) The University of Newcastle, Australia, NSW Awards Certificate awarded by the Faculty of Business & Law for: Finalist in the Annual “Three Minute Thesis” Competition (2013) at the University of Newcastle, Australia. Certificate Awarded by the Vice Chancellor Research for: Finalist in the Annual “Three Minute Thesis” Competition (2013) by the University of Newcastle, Australia. 2018 - 2019 Thematic Grant received from Higher Education Commission Pakistan under the project title “Role of Student Participation in Value Co- Creation: The Provision of Educational Support Services to The Higher Education Students in Pakistan Involving Service-Dominant Logic” for the year 2018-2019. 1998 Masters in Business Administration (MBA) Institute of Business Administration University of the Punjab, Lahore Pakistan 1996 Bachelors in Commerce Hailey College of Commerce University of the Punjab, Lahore Pakistan Awards: Roll of Honor for the year 1995 1992 Higher Secondary School Kinnaird College for Women, Lahore, Pakistan Awards: Scholarship granted from Board of Intermediary & Secondary Education BISE-LHR 1 1990 Primary & Secondary school Convent of Jesus & Mary (CJM) Lahore, Pakistan Awards Scholarship granted from Board of Intermediary & Secondary Education BISE-LHR Blue-card holder - issued by CJM authorities for best academic performance EXPERIENCE 2020- to date Director Institute of Business Administration -

Computer Science, Software Engineering, and Information Technology

CURRICULUM OF COMPUTER SCIENCE, SOFTWARE ENGINEERING, AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY (Bachelors & Masters Programs) (Revised 2017) HIGHER EDUCATION COMMISSION ISLAMABAD CURRICULUM DIVISION, HEC 1 Prof. Dr. Mukhtar Ahmed Chairman, HEC Prof. Dr. Arshad Ali Executive Director, HEC Mr. Muhammad Raza Chohan Director General (Academics) Dr. Muhammad Idrees Director (Curriculum) Syeda Sanober Rizvi Deputy Director (Curriculum) Mr. Riaz-ul-Haque Assistant Director (Curriculum) Mr. Muhammad Faisal Khan Assistant Director (Curriculum) 2 CONTENTS Contents CURRICULUM OF COMPUTING PROGRAMS .................................................... INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. Curricula Consideration .............................................................................................. Computing Discipline ................................................................................................. Introduction ................................................................................................................. Bachelor Degree Programs in Computing .................................................................. Eligibility Criteria ................................................................................................... Duration .................................................................................................................. Degree Completion Requirements ......................................................................... -

Curriculum of Architecture B. Arch (5-Year)

CURRICULUM OF ARCHITECTURE B. ARCH (5-YEAR) (Revised 2013) HIGHER EDUCATION COMMISSION SECTOR H-9, ISLAMABAD PAKISTAN CURRICULUM DIVISION, HEC Prof. Dr. Mukhtar Ahmed Executive Director Mr. Fida Hussain Director General (Acad) Mr. Rizwan Shoukat Deputy Director (Curr) Mr. Abid Wahab Assistant Director (Curr) Mr. Riaz-ul-Haque Assistant Director (Curr) 2 CONTENTS 1. Introduction ...................................................................................6 2. Framework for Bachelor in Architecture (5 years) .......................10 3. Scheme of Studies for Bachelor in Architecture (5 year) .... ......12 4. Detail of Courses for Bachelor in Architecture (5 year) ...............13 Annexure – A................................................................................27 Annexure – B................................................................................29 Annexure – C ...............................................................................31 3 PREFACE The curriculum, with varying definitions, is said to be a plan of the teaching-learning process that students of an academic programme are required to undergo. It includes objectives & learning outcomes, course contents, scheme of studies, teaching methodologies and methods of assessment of learning. Since knowledge in all disciplines and fields is expanding at a fast pace and new disciplines are also emerging; it is imperative that curricula be developed and revised accordingly. University Grants Commission (UGC) was designated as the competent authority to develop, -

Human Resource Development in Superior Group of Colleges Anam Saleem Anam Tariq Sajawal Malik M. Usman Hafiz Mushad Bilal Hakeem

Running head: HRD IN SUPERIOR GROUP OF COLLEGES 1 Human Resource Development in Superior Group of Colleges Anam Saleem Anam Tariq Sajawal Malik M. Usman Hafiz Mushad Bilal Hakeem University of the Punjab, Lahore. HRD IN SUPERIOR GROUP OF COLLEGES 2 Superior Group of Colleges Lahore is known as Pakistan's education capital, with more colleges and universities than any other city in the country. The current literacy rate of Lahore is 74%. Superior group of college started its journey in the year 2000 by establishing superior college Lahore near Kalma Chowk, within short span of time; it became love for people and their first choice owing to its quality education along with personality development, true professionalism and career planning. Vision “Our Alumni Our Identity” Mission To serve as a platform for the institute and its alumni to promote interaction by providing networking opportunities, sharing of experiences, mentoring, appreciating and highlighting their accomplishments that may contribute to their personal and professional lives. Charter and Recognition The Superior College, Lahore is included in the list of Higher Education Commission of Pakistan under the head of Recognized Universities and Degree Awarding Institutions. College got Charter by Govt. of the Punjab as degree awarding institute after having passed Superior College Bill from the Punjab Provincial Assembly on May 31, 2004. Superior University is also listed HRD IN SUPERIOR GROUP OF COLLEGES 3 with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)'s International Association of Universities. Research and Development Superior has been emphasizing on Research and Development in following ways: Research Centers Azra Naheed Center for Research & Development Ch. -

The Significance of Knowledge Sharing Tools In

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF KNOWLEDGE SHARING TOOLS IN HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS OF PUNJAB, PAKISTAN: MEDIATION MODEL OF SELF-DETERMINATION Thesis submitted to The Superior College Lahore In Partial fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration By Muhammad Khyzer Bin Dost Roll No. PDBA15109 Session: 2014-2017 THE SUPERIOR COLLEGE (SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT SCIENCES) LAHORE i Author’s Declaration I Muhammad Khyzer Bin Dost hereby state that my PhD thesis titled “The Significance of Knowledge Sharing Tools in Higher Education Institutions of Punjab, Pakistan: Mediation Model of Self-Determination” is my own work and has not been submitted previously by me for taking any degree from this University The Superior College, Lahore. Or anywhere else in the country/world. At any time if my statement is found to be incorrect even after my Graduate the university has the right to withdraw my PhD degree. Name of Student: Muhammad Khyzer Bin Dost Date: ________________ ii Plagiarism Undertaking I solemnly declare that research work presented in the thesis titled “The Significance of Knowledge Sharing Tools in Higher Education Institutions of Punjab, Pakistan: Mediation Model of Self-Determination” is solely my research work with no significant contribution from any other person. Small contribution/help wherever taken has been duly acknowledged and that complete thesis has been written by me. I understand the zero-tolerance policy of the HEC and University The Superior College, Lahore Towards plagiarism. Therefore, I as an Author of the above titled thesis declare that no portion of my thesis has been plagiarized and any material used as reference is properly referred/cited. -

Problems Faced by Foreign Students in Private Higher Education Institutions

Pakistan Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 2018, Vol. 16, No.2, 53-56 Problems Faced by International Students in Private Higher Education Institutions: An Exploratory Study Mahwish Zafar, Shazia Kousar & Ch. Abdul Rehman The Superior College Lahore Muqaddas Rehman Hailey College of Commerce,Lahore The enrollment of international students in higher education institutes (HEI) in Pakistan is increasing nowadays. The purpose of this study was to explore the academic experiences of international students in the natural setting of HEI. Human behaviors are subjective in nature; so this study used interpretative research paradigm to gain insight into the individual education experience in HEI. This study used a qualitative approach to understand the meanings of the student’s experiences in their own words. This study adopted convenient sampling to select international students in HEI and used semi-structured interview guide to explore their experiences related to academics, psychological issues, and society. This study used N-Vivo 11 Plus and derived two main themes; first academic challenge and second are psychological issues. The academic challenge consisted of three sub-themes like; academic progress, parent-teacher meetings, and the role of teacher. Similarly, psychological issues constituted on confusion, homesickness, and depression. The results revealed that 75 times students repeated that they were facing many academic obstructions in Pakistan and 56 times they discussed their psychological issues. Moreover, students repeatedly documented that their academic progress had been deteriorated and their grades had been worsened. Moreover, teacher behavior is biased towards international students because of a lack of communication between teachers and parents. Furthermore, international students feel homesickness, depression, and confusion in the absence of their family. -

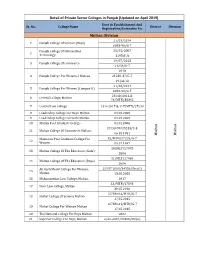

Detail of Private Sector Colleges in Punjab (Updated on April 2019) Date of Establishment and Sr

Detail of Private Sector Colleges in Punjab (Updated on April 2019) Date Of Establishment And Sr. No. College Name District Division Registration/Extension No. Multan Division 21/03/2014 1 Punjab College Of Science (Boys) 6083-90/G-7 Punjab College Of Information 25/05/2007 2 Technology 1193/P.A 29/07/2013 3 Punjab College Of Commerce 21238/G-7 2013 4 Punjab College For Women-I Multan 21230-37/G-7 29-Jul-13 21/03/2014 5 Punjab College For Women (Campus-Ii) 6092-99/G-7 28/10/2016 & 6 Central College, Multan 76/MTN/38342 7 Central Law College 13-9-2017 & 117/MTN/27249 8 Leadership College For Boys Multan. 01.05.2005 9 Leadership College For Girls Multan. 01.05.2005 10 Multan Post Graduate College 01.01.2006 27/53-90/29213/C-3 11 Multan College Of Commerce, Multan. 06.10.1991 Multan Multan Mamoona Post Graduate College For 82/MTN/27225/G-7 12 Women 01.07.1997 10/MLT/27978 13 Multan College Of The Educators (Girls) 2004 11/MLT/27969 14 Multan College Of The Educators (Boys) 2004 Ali Garh Model College For Women, 2/137-2008/34336/Dir.(G) 15 Multan. 13.08.2008 16 Mohammedan Law College, Multan. 2017 13/MTN/17845 17 Noor Law College, Multan 30.05.2016 1273No14/MTN/G-7 18 Nishat College Of Science Multan 17.05.2015 1273No14/MTN/G-7 19 Nishat College For Women Multan 17.05.2015 20 The National College For Boys Multan 2002 21 Superior College For Boys, Multan 2/42-2007/37488/Dir(G) 22 Superior College For Girls, Multan 2/43-2007/37495/Dir(G) International Degree College Of RP/2287 DATED 18-06-1986 23 Commerce Multan. -

Punjab-Government-Ru

Page 1 of 121 GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB SERVICES AND GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT (CABINET WING) Dated Lahore the 11th March, 2011 NOTIFICATION No.SO(Cab-I)2-3/2011.– In exercise of the powers conferred under Article 139 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Government of the Punjab is pleased to make the following Rules: PART-A GENERAL 1. Short title and commencement.– (1) These rules may be cited as the Punjab Government Rules of Business 20111. (2) They shall come into force at once. 2. Definitions.– In these rules, unless the context otherwise requires: (a) “Assembly” means the Provincial Assembly of the Punjab; (b) “Attached Department” means a department mentioned in column 3 of the First Schedule; (c) “Autonomous Body” means a Body mentioned in column 4 of the First Schedule; (d) “Business” means the work done by the Government; (e) “Cabinet” means the Cabinet of Ministers, with the Chief Minister at its head as mentioned in Article 130 of the Constitution; (f) “Case” means a particular matter under consideration and includes all papers pertaining to it and necessary for its disposal, such as correspondence and notes and any previous papers connected with the subject; (g) “Chief Secretary” means the officer notified as such in the Gazette, and includes Additional Chief Secretary in Services and General Administration Department; 2[(ga) “Commissioner”, “Additional Commissioner”, “Deputy Commissioner”, “Additional Deputy Commissioner” and “Assistant Commissioner” shall have the same meanings as are respectively assigned to them in the Punjab Civil Administration Act 2017 (III of 2017);] 1Approved by the Provincial Cabinet in its meeting held on March 08, 2011 in terms of Article 139 of the Constitution of the Islamic republic of Pakistan. -

Dr. Muhammad Ilyas Is Serving Government College Women University, Sialkot As Associate Professor of Economics and Chairperson of Economics Department

D r . MUHAMMAD ILYAS Address: Bilal Town, Kakailwali Road, Sialkot Mobile Phone: +92-344-4024824 E-Mail: [email protected] Mr. Dr. Muhammad Ilyas is serving Government College Women University, Sialkot as Associate Professor of Economics and Chairperson of Economics Department. He has done PhD in Economics from The Superior College, Lahore. He has rich experience of teaching students of post graduate level and is a research oriented fellow. During his professional career he actively participated in research projects originated by the Superior University and its subsidiaries Azra Nahid Center of Research and Development, Ch. Muhammad Akram Center of Entrepreneurship Development and AN Consultants. He has also done HEC funded research projects of national interest during his stay at GC Women University Sialkot. He has worked at GC Women University Sialkot in various roles e.g. as Treasurer, Project Director, Director Research, and Chairperson of Economics Department. His excellent managerial and teaching skills and abilities has earned him a lot of respect among the students and his colleagues always praise him because of his active participation and enthusiasm as a team member and leader in routine administrative and co- curricular activities. He believes in research based teaching and knows the art of integrating theory to practice. He is not only good in teaching the research specific data analysis software’s but also have used them in his academic and customized projects originated by various clients. EDUCATION PhD in ECONOMICS Economics Department, The Superior College, Lahore 2009-2012 A grade M. Phil. in ECONOMICS Economics Department, University of the Punjab, Lahore 2005-2007 CGPA = 3.86/4 MASTERS IN COMPUTER SCIENCES PUCIT 2001-2003 CGPA = 3.01/4 MASTERS IN ECONOMICS 1 Economics Department, University of the Punjab, Lahore 1999-2001 1st Division ACADEMIC DISTINCTIONS Throughout first class in the academic career Obtained HEC Indigenous Scholarship Merit Scholarship in M.