Findings from the Having a Baby in Queensland Survey, 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hospital and Health Service Public and Private Cancer Services Map 2019

Hospital and Health Service public and private cancer services map 2019 Central Integrated Regional Cancer Service Contents Hospital and Health Service Overviews ................................................................................ 3 Cairns and Hinterland ........................................................................................................ 5 Central Queensland ........................................................................................................... 7 Central West* .................................................................................................................... 9 Children's Health Queensland ......................................................................................... 11 Darling Downs ................................................................................................................. 13 Gold Coast ...................................................................................................................... 15 Mackay ............................................................................................................................ 17 Metro North ..................................................................................................................... 19 Metro South ..................................................................................................................... 22 North West* ..................................................................................................................... 24 South -

Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 3 Budget.Qld.Gov.Au Queensland Budget 2021–22 Budget Queensland Capital Statement Budget Paper No

Queensland Budget Budget Queensland QUEENSLAND BUDGET 2021–22 2021 – 22 Capital Statement Statement Capital CAPITAL STATEMENT Budget Paper No. Paper Budget BUDGET PAPER NO. 3 3 Queensland Budget 2021–22 Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 budget.qld.gov.au budget.qld.gov.au 21-050_Budget 2021-22 _A4_Core Paper_Cover.indd 5 7/6/21 3:44 pm 2021–22 Queensland Budget Papers 1. Budget Speech 2. Budget Strategy and Outlook 3. Capital Statement Service Delivery Statements Appropriation Bills Budget Highlights Regional Action Plans The budget papers are available online at budget.qld.gov.au © The State of Queensland (Queensland Treasury) 2021 Copyright This publication is protected by the Copyright Act 1968 Licence This document is licensed by the State of Queensland (Queensland Treasury) under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) International licence. In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt this publication, as long as you attribute the work to the State of Queensland (Queensland Treasury). To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Attribution Content from this publication should be attributed to: © The State of Queensland (Queensland Treasury) - 2021–22 Queensland Budget Translating and interpreting assistance The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders from all cultural and linguistic backgrounds. If you have difficulty in understanding this publication, you can contact us on telephone (07) 3035 3503 and we will arrange an interpreter to effectively communicate the report to you. Capital Statement Budget Paper No. 3 ISSN 1445-4890 (Print) ISSN 1445-4904 (Online) Queensland Budget 2021–22 Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 21-050_Budget 2021-22 _A4_Core Paper_Cover.indd 6 7/6/21 3:44 pm Capital Statement 2021–22 State Budget 2021–22 Capital Statement Budget Paper No. -

Capital Statement Capital Stateme

PleasePlease adjust adjust spine spine widthwidth accordingly accordingly Queensland Budget 2020 Budget Queensland 2020 Budget Queensland QUEENSLANDQUEENSLAND BUDGETBUDGET 2020-212020-21 – – 21 21 Capital Statement Statement Capital Statement Capital CAPITALCAPITAL STATEMENTSTATEMENT Budget Paper No. Paper Budget No. Paper Budget BUDGETBUDGET PAPERPAPER NO.NO. 33 3 3 QueenslandQueensland Budget Budget 2020–21 2020–21 CapitalCapital Statement Statement Budget Budget Paper Paper No. No.33 ~ Queensland budget.qld.gov.aubudget.qld.gov.au budget.qld.gov.aubudget.qld.gov.au Government PleasePlease adjust adjust spine spine widthwidth accordingly accordingly Please adjust spine width accordingly 2020–21 Queensland Budget Papers 1. Budget Speech 2. Budget Strategy and Outlook 3. Capital Statement Service Delivery Statements Appropriation Bills Budget Highlights Regional Action Plans The Budget Papers are available online at budget.qld.gov.au © The State of Queensland (Queensland Treasury) 2020 Copyright This publication is protected by the Copyright Act 1968 Licence This document is licensed by the State of Queensland (Queensland Treasury) under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) International licence. In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt this publication, as long as you attribute the work to the State of Queensland (Queensland Treasury). To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Attribution Content from this publication should be attributed to: © The State of Queensland (Queensland Treasury) - 2020–21 Queensland Budget Translating and interpreting assistance The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders from all cultural and linguistic backgrounds. If you have difficulty in understanding this publication, you can contact us on telephone (07) 3035 3503 and we will arrange an interpreter to effectively communicate the report to you. -

Far North Region

FAR NORTH REGION The Far North region covers the large and diverse region from Tully in the south to the Torres Strait in the north and Croydon in the west. This region follows the Far North Queensland Medicare Local boundaries. REGIONAL HEALTH ORGANISATIONS The Far North region comprises of the following Medicare Local, Hospital and Health Services and Regional Aboriginal and Islander Community Controlled Health Organisation. CheckUP and QAIHC in collaboration with regional health organisations will support the delivery of outreach heatlh services under the Rural Health Outreach Fund (RHOF) and the Medical Outreach Indigenous Chronic Disease Program (MOICDP). Outreach Medicare Local Hospital and Health Regional Aboriginal and Islander Region Services Community Controlled Health Organisation Far North Far North Torres Strait and Far North Queensland Northern Peninsula Cairns and Hinterland Cape York Health Organisations Medicare Local Far North Queensland Medicare Local Cape York HHS The HHS operates 2 multi-purpose facilities at: Cooktown Weipa 10 Primary Healthcare Centres are also located at: Aurukun Coen Hopevale Laura Lockhart River Kowanyama Mapoon Napranum Pormpuraaw Wujal Wujal Cairns and Hinterland HHS Atherton Hospital Babinda Hospital Cairns Base Hospital Gordonvale Memorial Hospital Herberton Hospital/Aged Care Unit Innisfail Hospital Mareeba Hospital Mossman Multi-Purpose Health Service Tully Hospital Community Health Centres at: Edmonton, Westcourt, Smithfield, Cairns, Atherton, Mareeba, Yarrabah Mossman, Cow Bay, Innisfail, Cardwell, Tully, Jumbun, Mission Beach Primary Health Care Centres at: Malanda, Millaa Millaa, Mount Garnet, Ravenshoe, Georgetown, Dimbulah Forsayth, Croydon, Chillagoe and Yarrabah Torres Strait and Northern Peninsula HHS Thursday Island Hospital Bamaga Hospital Primary Health Care Centres (21) including Thursday Island Primary Health Care Centre and centres located on the outer islands. -

Mackay Hospital and Health Service

Mackay Hospital and Health Service Acknowledgement Recognition of Australian to Traditional Owners South Sea Islanders The Mackay Hospital and Health Service The Mackay Hospital and Health Service formally acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of the recognises the Australian South Sea Islanders land and waters of all areas within our geographical as a distinct cultural group within our geographical boundaries. We pay respect to the Aboriginal and boundaries. The Mackay Hospital and Health Service Torres Strait Islander Elders past, present and is committed to fulfilling the Queensland Government those yet to come on whose land we provide health Recognition Statement for Australian South Sea services as we make tracks towards closing the gap. Islander Community to ensure “that present and future generations of Australian South Sea Islanders The Mackay Hospital and Health Service is have equality of opportunity to participate in committed to Closing the Gap Initiative targets: and contribute to the economic, social, political • to close the gap in life expectancy within and cultural life of the State”. a generation (by 2031); and • to halve the gap in mortality rates for Indigenous children under five by 2018. Licence Interpreter Service Statement This annual report is licensed by Mackay Hospital and Health Service Mackay Hospital and Health Service Annual Report 2016–2017 under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) 3.0 Australia Licence. The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible CC by Licence Summary Statement services to Queenslanders from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. If you have difficulty in understanding the annual report, In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt this you can contact us on (07) 4885 5984 and we will arrange an interpreter annual report, as long as you attribute the work to the Mackay to effectively communicate the report to you. -

Far North Region

FAR NORTH REGION The Far North region covers the large and diverse region from Tully in the south to the Torres Strait in the north and Croydon in the west. This region follows the Far North Queensland Medicare Local boundaries. REGIONAL HEALTH ORGANISATIONS The Far North region comprises of the following Medicare Local, Hospital and Health Services and Regional Aboriginal and Islander Community Controlled Health Organisation. CheckUP and QAIHC in collaboration with regional health organisations will support the delivery of outreach heatlh services under the Rural Health Outreach Fund (RHOF) and the Medical Outreach Indigenous Chronic Disease Program (MOICDP). Outreach Medicare Local Hospital and Health Regional Aboriginal and Islander Region Services Community Controlled Health Organisation Far North Far North Torres Strait and Far North Queensland Northern Peninsula Cairns and Hinterland Cape York Health Organisations Medicare Local Far North Queensland Medicare Local Hospital and Cape York HHS Health Services (HHS) The HHS operates 2 multi-purpose facilities at: Cooktown Weipa 10 Primary Healthcare Centres are also located at: Aurukun, Coen Hopevale Laura Lockhart River Kowanyama Mapoon Napranum Pormpuraaw Wujal Wujal Cairns and Hinterland HHS Atherton Hospital Babinda Hospital Cairns Base Hospital Gordonvale Memorial Hospital Herberton Hospital/Aged Care Unit Innisfail Hospital Mareeba Hospital Mossman Multi-Purpose Health Service Tully Hospital Torres Strait and Northern Peninsula HHS Thursday Island Hospital -

The Good Egg

SECOND EDITION 2017 helping kids in hospital THEA plaque recognising your GOODdonation will be attached to the equipment EGG purchased 3 EDITORIAL TEAM Editor in Chief: Julie Abbott What’s Inside Assistant Editor: Paul Francis OAM Production/Design: Sally Robinson Message from the Chairman 1 Hannah’s Story 2 Writer: Humpty in the Northern Territory 5 Ray Martin AM Humpty’s Kokoda Adventure 8 Writer: Lauren’s Update 14 Jeff Zulman Humpty’s Reach 16 How Humpty’s Wish List Works 19 Writer: Sue Channon Chairman’s Medical Wishes 20 Humpty’s Medical Wish List 21 Humpty Facts 27 Ways You Can Help 28 HUMPty DUMPty Foundation Board Paul Francis OAM John Bevan CONGRATULATIONS Judy Cotton Long time Humpty Ambassador Phil Kerry Chikarovski Kearns AM was appointed a Member Merran Edwards of the Order of Australia earlier this Jane Flemming OAM year for his significant service to the Paul Jeffery community through his support of Prof Martin Kluckow Dr Jonny Taitz charitable organisations, to business Nigel Watts and to rugby union at the elite level. It was Phil who came up with the HUMPty TEAM idea for the Balmoral Burn, and now Paul Francis OAM Julie Abbott 17 years later, it has raised over $30 Kate Bull million for the Humpty Dumpty Foundation to purchase essential, Belinda Munro often life-saving medical equipment for children’s hospitals, right Bonnie Ratcliff across Australia. Claire Reaney (Maternity Leave) Joanna Seremet Congratulations Phil and thank you for all that you have done Stella Sung for Aussie kids – you are a true champion! THANK YOU A huge thank you to our editors, writers, designer and printers for donating their time and expertise to Humpty to help produce this edition of The Good Egg. -

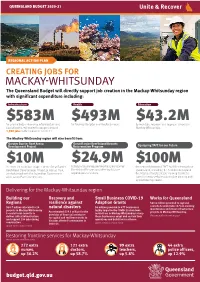

MACKAY-WHITSUNDAYCREATING JOBS on the Training in 2020–21 $17.5B Enhancing Frontline Services

DO NOT REMOVE KEYLINE CREATING JOBS FOR QUEENSLAND CREATING JOBS FOR QUEENSLAND CREATING JOBS FOR QUEENSLAND Lorem ipsum CREATING JOBS FOR QUEENSLAND reverse CREATING JOBS of above FORQUEENSLAND QUEENSLAND BUDGET 2020-21 BUDGET 2020–21 STATEWIDE AT A GLANCE HIGHLIGHTS CREATING Jobs supported by infrastructure This Budget is focused on creating JOBS FOR investment in 2020–21 46,000 jobs and getting our economy moving QUEENSLAND Total infrastructure program over four years $56B sooner. Initiatives include: Percentage of capital spend Driving the largest Growing our regions and outside Greater Brisbane 58% infrastructure program in over supporting key industries such a decade - $14.8 billion in as tourism, agriculture and REGIONAL ACTION PLAN Total spend on road and transport 2020–21, directly supporting mining. An additional For RAPSs infrastructure in 2020–21 $6.3B 46,000 jobs. Around 58% $200 million will be provided of the capital program and to the Works for Queensland COVID-19 economic stimulus 28,700 of the jobs supported program to support local CREATING JOBS FOR THE measures to date $7B will be outside the Greater governments outside South Brisbane area. East Queensland. Education and MACKAY-WHITSUNDAYCREATING JOBS ON THE training in 2020–21 $17.5B Enhancing frontline services. Providing more Queenslanders The Budget will support with access to the skills and The Queensland Budget will directly support job creation in the Mackay-Whitsunday region Health in 2020–21 funding for additional training they need for rewarding with significant expenditure including: $21.8B frontline health staff including careers. $100 million has been provided over three years to Concessions and lowering the 5,800 nurses, 1,500 doctors CREATINGInfrastructure JOBS FORHealth THE Education cost of living and 1,700 allied health upgrade TAFE campuses. -

International Directory of Hospitals

healthcare international directory of hospitals membership information what you need to know your international directory of hospitals Welcome Welcome to your international directory of hospitals listing those hospitals worldwide with which we have a direct settlement agreement for in-patient care. This directory forms part of the terms of your policy. Wherever you are in the world, your directory will help you and your medical practitioner to select a hospital should you need in-patient treatment. Please keep it in a convenient place in case you need it. contents section page number this section explains: 1 introduction 3 • what your directory tells you • how to use your directory • how to arrange direct settlement 5 • what happens with out-patient-treatment • third party local knowledge 2 international directory • where you can receive treatment in the of hospitals following parts of world 7 • Caribbean 8 • Central America 9 • South America 10 • India 11 • Canada 12 • Africa 13 • Asia 50 • Australasia 66 • North America 459 • Europe 524 • Middle East Information is correct as at October 2014 2 1 introduction What your directory tells you Your international directory of hospitals lists all the hospitals worldwide with which AXA has what is known as a direct settlement agreement for in-patient care. This means that, if you receive in-patient treatment at any of the named hospitals, we will pay your eligible bills direct to them, providing that we have agreed your treatment in advance. It means you won’t have the worry of having to pay in advance for your in-patient care and then claiming reimbursement from us. -

Whitsunday Investment Prospectus Introduction from the Mayor

WHITSUNDAY INVESTMENT PROSPECTUS Introduction from the Mayor The Whitsundays is about lifestyle, opportunity and prosperity. In the heart of tropical Northern Queensland situated sustainable and universally between the major towns of Mackay and Townsville, recognised as the region we boast a nationally and internationally recognised where people want to live, ‘Whitsunday brand’ that has established our region as work, learn and invest. a tourism and boating mecca in the heart of the The future for the Great Barrier Reef. Whitsundays is exciting with The region has economic resilience with the Gross strong investment, business Regional Product of the Whitsunday LGA estimated at and industry opportunities approximately $2.46 billion in 2017. With over $4.7 billion and I invite you to be a part of it. We are inviting in major projects planned or under construction, the region government and commercial proponents to make the is expecting rapid growth over the next 10 years. Whitsundays your global region of choice for investment in our Agricultural, Resource and Tourism industries. Council owns and operates the Whitsunday Coast Airport which is one of the fastest growing regional airports in Major infrastructure developments, commercial, industrial Australia with passenger numbers doubling in the last and tourism investment and expanded community facilities five years. To cater for this incredible growth Council has will provide business opportunities in the Whitsundays invested $40 million in the 2017/18 financial year to ensuring future economic growth and sustainability. improve infrastructure with a runway upgrade and airport This has always been at the core of my agenda as Mayor. -

Queensland Government Gazette

Queensland Government Gazette PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. 376] Friday 10 November 2017 General Gazette Notices All submissions to the'ENERAL 'AZETTEMUSTBERECEIVEDBEFORE OPPOPO8FEOFTEBZT For example: n Departmental Notices n DispoSal oF Unclaimed Good S n Land sales / Resumption of Land n Dissolution of Partnership Notices n Unclaimed Monies Email your submission in Word or PDF Format to HB[FUUF!IQXRMEHPWBV !PROOFISFORMATTEDANDEMAILEDTOYOU ALONGWITHAQUOTATIONFORYOURAPPROVAL 0AYMENTINDICATESTHE PROOFISAPPROVEDTOBEPUBLISHED 4HEGJOBMBQQSPWBMTOPUBLISHMUSTBE COMPLETEDBYCLOSEOFBUSINESS7EDNESDAY TOBEINCLUDEDIN&RIDAYS'AZETTE 4HEWEEKS#OMBINED'AZETTEISPLACEDONLINE &RIDAYMORNINGANDCANBEDOWNLOADED ORVIEWEDAT XXXRMEHPWBVQVCMJDBUJPOT [323] Queensland Government Gazette Extraordinary PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. 376] Saturday 4 November 2017 [No. 68 Queensland Constitution of Queensland 2001 PROCLAMATION I, PAUL de JERSEY AC, Governor, acting under section 41 of the Constitution of Queensland 2001, have today resumed the administration of the Government of the State. [L.S.] PAUL de JERSEY Governor Signed and sealed on 4 November 2017. By Command Annastacia Palaszczuk God Save the Queen ENDNOTES 1. Made by the Governor on 4 November 2017. 2. Published in an Extraordinary Government Gazette on 4 November 2017. 3. The administering agency is the Department of the Premier and Cabinet. © The State of Queensland 2017 Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited without prior written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to: Gazette Advertising, GPO Box 2457, Brisbane QLD 4001. _____________________________ BRISBANE 4 November 2017 324 QUEENSLAND GOVERNMENT GAZETTE No. 68 [4 November 2017 This page has been left blank intentionally [325] Queensland Government Gazette Extraordinary PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. 376] Tuesday 7 November 2017 [No. -

Covid-19 Economic Recovery Plan

QUEENSLAND BUDGET 2021–22 QUEENSLAND’S COVID-19 ECONOMIC RECOVERY PLAN Budget update budget.qld.gov.au © The State of Queensland 2021 Attribution Content from the Queensland's COVID-19 Economic Recovery Plan – Copyright Budget update should be attributed to: © The State of Queensland, This publication is protected by the Copyright Act 1968 Queensland's Economic Recovery Plan – Budget update. Licence Translating and interpreting assistance This document is licensed by the State of Queensland under a The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) International licence. services to Queenslanders from all cultural and linguistic backgrounds. If you have difficulty in understanding this publication, you can contact us on telephone (07) 3035 3503 and we will arrange an interpreter to effectively communicate the report to you. In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt this Find our report online publication, as long as you attribute the work to the State of Queensland (Queensland Treasury). To view a copy of this licence, covid19.qld.gov.au visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Contents 4 QUEENSLAND'S RECOVERY 6 SAFEGUARDING OUR HEALTH 8 BACKING SMALL BUSINESS 10 MAKING IT FOR QUEENSLAND 12 BUILDING QUEENSLAND 14 GROWING OUR REGIONS 20 INVESTING IN SKILLS 22 POSITIONING FOR THE FUTURE JUNE 2021 3 QUEENSLAND'S Queensland is the place to be. RECOVERY The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged Queenslanders like never before. Its impacts have been felt by individuals, families, businesses and communities across the state. The Queensland Government’s Economic Faster domestic More jobs recovered Faster workforce Recovery Plan has provided a decisive Safeguarding Building economic growth than than any other state participation growth and effective response to the COVID-19 our health Queensland the rest of Australia or territory than any other state health and economic crisis.