In Search of Shelter the Case of Hawassa, Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Exploring Barriers Related to the Use of Latrine and Health Impacts In

Research Article iMedPub Journals Health Science Journal 2017 http://www.imedpub.com/ Vol.11 No.2:492 ISSN 1791-809X DOI: 10.21767/1791-809X.1000492 Exploring Barriers Related to the Use of Latrine and Health Impacts in Rural Kebeles of Dirashe District Southern Ethiopia: Implications for Community Lead Total Sanitations Wanzahun Godana1 and Bezatu Mengistie2 1Department of Public Health, Arba Minch University, Arba Minch, Ethiopia 2School of Public Health, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia Corresponding author: Wanzahun Godana, Department of Public Health, Arba Minch University, Arba Minch, Ethiopia, Tel: 251913689198; E- mail: [email protected] Received date: 17 February 2017; Accepted date: 15 March 2017; Published date: 23 March 2017 Copyright: © 2017 Godana W, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the creative Commons attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Citation: Godana W, Mengistie B. Exploring Barriers Related to the Use of Latrine and Health Impacts in Rural Kebeles of Dirashe District Southern Ethiopia: Implications for Community Lead Total Sanitations. Health Sci J 2017, 11: 2. than its merely physical presence, the health status of the Abstract people improves [1,4]. Unsanitary disposal of human excreta, together with unsafe Unsanitary disposal of human excreta, together with drinking water and poor hygiene conditions contribute for 88% unsafe drinking water and poor hygiene -

COUNTRY Food Security Update

ETHIOPIA Food Security Outlook Update September 2013 Crops are at their normal developmental stages in most parts of the country Figure 1. Projected food security outcomes, KEY MESSAGES September 2013 • Following the mostly normal performance of the June to September Kiremt rains, most crops are at their normally expected developmental stage. A near normal Meher harvest is expected in most parts of the country. However, in places where Kiremt rains started late and in areas where some weather-related hazards occurred, some below normal production is anticipated. • Market prices of most staple cereals remain stable at their elevated levels compared to previous months, but prices are likely to fall slightly starting in October due to the expected near normal Meher production in most parts of the country, which, in turn, will also improve household-level food access from October to December. Source: FEWS NET Ethiopia • Overall, current nutritional status compared to June/July has slightly improved or remains the same with exceptions in Figure 2. Projected food security outcomes, some areas in northeastern Tigray and Amhara Regions as October to December 2013 well as some parts of East Hararghe Zone in Oromia Region. In these areas, there are indications of deteriorating nutritional status due to the well below average Belg harvest and the current absence of a green harvest from long-cycle Meher crops. CURRENT SITUATION • Cumulative Kiremt rainfall from June to September was normal to above normal and evenly distributed in all of Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR), in most parts of Amhara, in central and western parts Oromia, and in the central parts of Tigray. -

Prevalence and Factors Associated with Overweight And

Darebo et al. BMC Obesity (2019) 6:8 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40608-019-0227-7 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Prevalence and factors associated with overweight and obesity among adults in Hawassa city, southern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study Teshale Darebo1, Addisalem Mesfin2* and Samson Gebremedhin3 Abstract Background: In Ethiopia, limited information is available about the epidemiology of over-nutrition. This study assessed the prevalence of, and factors associated with overweight and obesity among adults in Hawassa city, Southern Ethiopia. Methods: A community-based cross-sectional survey was conducted in August 2015 in the city. A total of 531 adults 18–64 years of age were selected using multistage sampling approach. Interviewer administered qualitative food frequency questionnaire was used to assess the consumption pattern of twelve food groups. The level of physical exercise was measured via the General Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). Based on anthropometric measurements, Body Mass Index (BMI) was computed and overweight including obesity (BMI of 25 or above) was defined. For identifying predictors of overweight and obesity, multivariable binary logistic regression model was fitted and the outputs are presented using Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI). Results: The prevalence of overweight including obesity was 28.2% (95% CI: 24.2–32.2). Significant proportions of adults had moderate (37.6%) or low (2.6%) physical activity level. As compared to men, women had 2.56 (95% CI: 1.85–4.76) times increased odds of overweight/obesity. With reference to adults 18–24 years of age, the odds were three times higher among adults 45–54 (3.06, 95% CI: 1.29–7.20) and 55–64 (2.88, 95% CI: 1.06–7.84) years. -

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010 R Legend Eritrea E Tigray R egion !ª D 450 ho uses burned do wn d ue to th e re ce nt International Boundary !ª !ª Ahferom Sudan Tahtay Erob fire incid ent in Keft a hum era woreda. I nhabitan ts Laelay Ahferom !ª Regional Boundary > Mereb Leke " !ª S are repo rted to be lef t out o f sh elter; UNI CEF !ª Adiyabo Adiyabo Gulomekeda W W W 7 Dalul E !Ò Laelay togethe r w ith the regiona l g ove rnm ent is Zonal Boundary North Western A Kafta Humera Maychew Eastern !ª sup portin g the victim s with provision o f wate r Measle Cas es Woreda Boundary Central and oth er imm ediate n eeds Measles co ntinues to b e re ported > Western Berahle with new four cases in Arada Zone 2 Lakes WBN BN Tsel emt !A !ª A! Sub-city,Ad dis Ababa ; and one Addi Arekay> W b Afa r Region N b Afdera Military Operation BeyedaB Ab Ala ! case in Ahfe rom woreda, Tig ray > > bb The re a re d isplaced pe ople from fo ur A Debark > > b o N W b B N Abergele Erebtoi B N W Southern keb eles of Mille and also five kebeles B N Janam ora Moegale Bidu Dabat Wag HiomraW B of Da llol woreda s (400 0 persons) a ff ected Hot Spot Areas AWD C ases N N N > N > B B W Sahl a B W > B N W Raya A zebo due to flo oding from Awash rive r an d ru n Since t he beg in nin g of th e year, Wegera B N No Data/No Humanitarian Concern > Ziquala Sekota B a total of 967 cases of AWD w ith East bb BN > Teru > off fro m Tigray highlands, respective ly. -

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008)

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008) ma, maa (O) why? HES37 Ma 1258'/3813' 2093 m, near Deresge 12/38 [Gz] HES37 Ma Abo (church) 1259'/3812' 2549 m 12/38 [Gz] JEH61 Maabai (plain) 12/40 [WO] HEM61 Maaga (Maago), see Mahago HEU35 Maago 2354 m 12/39 [LM WO] HEU71 Maajeraro (Ma'ajeraro) 1320'/3931' 2345 m, 13/39 [Gz] south of Mekele -- Maale language, an Omotic language spoken in the Bako-Gazer district -- Maale people, living at some distance to the north-west of the Konso HCC.. Maale (area), east of Jinka 05/36 [x] ?? Maana, east of Ankar in the north-west 12/37? [n] JEJ40 Maandita (area) 12/41 [WO] HFF31 Maaquddi, see Meakudi maar (T) honey HFC45 Maar (Amba Maar) 1401'/3706' 1151 m 14/37 [Gz] HEU62 Maara 1314'/3935' 1940 m 13/39 [Gu Gz] JEJ42 Maaru (area) 12/41 [WO] maass..: masara (O) castle, temple JEJ52 Maassarra (area) 12/41 [WO] Ma.., see also Me.. -- Mabaan (Burun), name of a small ethnic group, numbering 3,026 at one census, but about 23 only according to the 1994 census maber (Gurage) monthly Christian gathering where there is an orthodox church HET52 Maber 1312'/3838' 1996 m 13/38 [WO Gz] mabera: mabara (O) religious organization of a group of men or women JEC50 Mabera (area), cf Mebera 11/41 [WO] mabil: mebil (mäbil) (A) food, eatables -- Mabil, Mavil, name of a Mecha Oromo tribe HDR42 Mabil, see Koli, cf Mebel JEP96 Mabra 1330'/4116' 126 m, 13/41 [WO Gz] near the border of Eritrea, cf Mebera HEU91 Macalle, see Mekele JDK54 Macanis, see Makanissa HDM12 Macaniso, see Makaniso HES69 Macanna, see Makanna, and also Mekane Birhan HFF64 Macargot, see Makargot JER02 Macarra, see Makarra HES50 Macatat, see Makatat HDH78 Maccanissa, see Makanisa HDE04 Macchi, se Meki HFF02 Macden, see May Mekden (with sub-post office) macha (O) 1. -

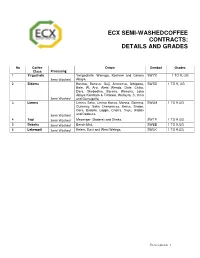

Ecx Semi-Washedcoffee Contracts: Details And

ECX SEMI -WASHED COFFEE CONTRACTS: DETAILS AND GRADES No Coffee Origin Symbol Grades Class Processing 1 Yir gachefe Yerigachefe, Wenago, Kochere and Gelana SWYC 1 TO 9, UG Semi Washed Abaya. 2 Sidama Borena, Benssa, Guji, Arroressa, Arbigona, SWSD 1 TO 9, UG Bale, W. Arsi. Aleta Wendo, Dale, Chiko, Dara, Shebedino, Borena, Wensho, Loko Abaya Kembata & Timbaro, Wellayta, S. Omo Semi Washed and Gamugoffa. 3 Limmu Limmu Seka, Limmu Kossa, Manna, Gomma, SWLM 1 TO 9,UG Gummay, Seka Chekoressa, Kersa, Shebe, Gera, Bedelle, Loppa, Chorra, Yayu, Alididu Semi Washed and Dedessa. 4 Tepi Semi Washed Mezenger (Godere) and Sheka. SWTP 1 TO 9,UG 5 Bebeka Semi Washed Bench Maji. SWBB 1 TO 9,UG 6 Lekempti Semi Washed Kelem, East and West Welega. SWLK 1 TO 9,UG _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ECX Contracts 1 ECX SEMI-WASHED COFFEE CONTRACTS: GRADES AND STANDARDS General requirements The moisture content of semi-washed coffee shall not be more than 11.5% by weight. DEFINITIONS Semi -washed Coffee Coffee that is pulped but unfermented. Cherries are washed and sorted as in the washed method but are not placed in the fermentation tanks. Moisture Content The moisture content, expressed on a wet weight bases, shall be determined using an approved moisture meter. Raw Value The sum of points of Shape & Make, Colour and Odour. Cup Quality Value The sum of points of Cup Cleanness, Acidity, Body and Flavour. Liquoring (Cup testing) The organoleptic examination of brewed coffee by professionals to determine acidity, body and flavor, detection of defects and characters. Cup Defect The number of cup defects out of five cups. -

Preservice Laboratory Education Strengthening Enhances

Fonjungo et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, 11:56 http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/11/1/56 RESEARCH Open Access Preservice laboratory education strengthening enhances sustainable laboratory workforce in Ethiopia Peter N Fonjungo1,8*, Yenew Kebede1, Wendy Arneson2, Derese Tefera1, Kedir Yimer1, Samuel Kinde3, Meseret Alem4, Waqtola Cheneke5, Habtamu Mitiku6, Endale Tadesse7, Aster Tsegaye3 and Thomas Kenyon1 Abstract Background: There is a severe healthcare workforce shortage in sub Saharan Africa, which threatens achieving the Millennium Development Goals and attaining an AIDS-free generation. The strength of a healthcare system depends on the skills, competencies, values and availability of its workforce. A well-trained and competent laboratory technologist ensures accurate and reliable results for use in prevention, diagnosis, care and treatment of diseases. Methods: An assessment of existing preservice education of five medical laboratory schools, followed by remedial intervention and monitoring was conducted. The remedial interventions included 1) standardizing curriculum and implementation; 2) training faculty staff on pedagogical methods and quality management systems; 3) providing teaching materials; and 4) procuring equipment for teaching laboratories to provide practical skills to complement didactic education. Results: A total of 2,230 undergraduate students from the five universities benefitted from the standardized curriculum. University of Gondar accounted for 252 of 2,230 (11.3%) of the students, Addis Ababa University for 663 (29.7%), Jimma University for 649 (29.1%), Haramaya University for 429 (19.2%) and Hawassa University for 237 (10.6%) of the students. Together the universities graduated 388 and 312 laboratory technologists in 2010/2011 and 2011/2012 academic year, respectively. -

Ethiopia Socio-Economic Assessment of the Impact of COVID-19

ONE UN ASSESSMENT ETHIOPIA ADDIS ABABA MAY 2020 SOCIO - ECONOMIC IMPACT of COVID‑19 in ETHIOPIA ABOUT This document is a joint product of the members of the United Nations Country Team in Ethiopia. The report assesses the devastating social and economic dimensions of the COVID-19 crisis and sets out the framework for the United Nations’ urgent socio- economic support to Ethiopia in the face of a global pandemic. FOREWORD BY THE UN RESIDENT / HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR This socio-economic impact assessment has been This assessment aligns fully with the ‘UN framework drafted by the United Nations (UN) in Ethiopia in for the immediate socio-economic response to the spirit of ‘One UN’. It reflects our best collective COVID-19’ launched by the Secretary-General in assessment, based on the available evidence and April 2020, even though its design and preparation our knowledge and expertise, of the scale, nature preceded the publication of this vital reference and depth of socio-economic impacts in the country. document. This assessment addresses all aspects of We offer this as a contribution to the expanding the framework, in terms of the people we must reach; knowledge base on this critical issue, acknowledging the five pillars of the proposed UN response – health and drawing upon the work of the Government of first, protecting people, economic response and Ethiopia (GoE), academic experts, development recovery, macroeconomic response and multilateral partners and consulting firms, among others. collaboration, community cohesion and community resilience; and the collective spirt deployed to deliver Given the high level of uncertainty and volatility in the product and our upcoming socio-economic conditions, whether in Ethiopia or outside - not least response. -

Aalborg Universitet Restructuring State and Society Ethnic

Aalborg Universitet Restructuring State and Society Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia Balcha, Berhanu Publication date: 2007 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Balcha, B. (2007). Restructuring State and Society: Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia. SPIRIT. Spirit PhD Series No. 8 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: November 29, 2020 SPIRIT Doctoral Programme Aalborg University Kroghstraede 3-3.237 DK-9220 Aalborg East Phone: +45 9940 9810 Mail: [email protected] Restructuring State and Society: Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia Berhanu Gutema Balcha SPIRIT PhD Series Thesis no. 8 ISSN: 1903-7783 © 2007 Berhanu Gutema Balcha Restructuring State and Society: Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia SPIRIT – Doctoral Programme Aalborg University Denmark SPIRIT PhD Series Thesis no. -

Prioritization of Shelter/NFI Needs

Prioritization of Shelter/NFI needs Date: 31st May 2018 Shelter and NFI Needs As of 18 May 2018, the overall number of displaced people is 345,000 households. This figure is based on DTM round 10, partner’s assessments, government requests, as well as the total of HH supported since July 2017. The S/NFI updated its prioritisation in early May and SNFI Cluster partners agreed on several criteria to guide prioritisation which include: - 1) type of emergency, 2) duration of displacement, and 3) sub-standard shelter conditions including IDPS hosted in collective centres and open-air sites and 4) % of vulnerable HH at IDP sites. Thresholds for the criteria were also agreed and in the subsequent analysis the cluster identified 193 IDP hosting woredas mostly in Oromia and Somali regions, as well as Tigray, Gambella and Addis Ababa municipality. A total of 261,830 HH are in need of urgent shelter and NFI assistance. At present the Cluster has a total of 57,000 kits in stocks and pipeline. The Cluster requires urgent funding to address the needs of 204,830 HHs that are living in desperate displacement conditions across the country. This caseload is predicted to increase as the flooding continues in the coming months. Shelter and NFI Priority Activities In terms of priority activities, the SNFI Cluster is in need of ES/NFI support for 140,259 HH displaced mainly due to flood and conflict under Pillar 2, primarily in Oromia and Somali Regions. In addition, the Shelter and NFI Cluster requires immediate funding for recovery activities to support 14,000 HH (8,000 rebuild and 6,000 repair) with transitional shelter support and shelter repair activities under Pillar 3. -

World Bank Document

Sample Procurement Plan (Text in italic font is meant for instruction to staff and should be deleted in the final version of the PP) Public Disclosure Authorized (This is only a sample with the minimum content that is required to be included in the PAD. The detailed procurement plan is still mandatory for disclosure on the Bank’s website in accordance with the guidelines. The initial procurement plan will cover the first 18 months of the project and then updated annually or earlier as necessary). I. General 1. Bank’s approval Date of the procurement Plan: Updated Procurement Plan, M 2. Date of General Procurement Notice: Dec 24, 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized 3. Period covered by this procurement plan: The procurement period of project covered from year June 2010 to December 2012 II. Goods and Works and non-consulting services. 1. Prior Review Threshold: Procurement Decisions subject to Prior Review by the Bank as stated in Appendix 1 to the Guidelines for Procurement: [Thresholds for applicable procurement methods (not limited to the list below) will be determined by the Procurement Specialist /Procurement Accredited Staff based on the assessment of the implementing agency’s capacity.] Public Disclosure Authorized Procurement Method Prior Review Comments Threshold US$ 1. ICB and LIB (Goods) Above US$ 500,000 All 2. NCB (Goods) Above US$ 100,000 First contract 3. ICB (Works) Above US$ 15 million All 4. NCB (Works) Above US$ 5 million All 5. (Non-Consultant Services) Below US$ 100,000 First contract [Add other methods if necessary] 2. Prequalification. Bidders for _Not applicable_ shall be prequalified in accordance with the provisions of paragraphs 2.9 and 2.10 of the Public Disclosure Authorized Guidelines.