Abdus Salam: a Reappraisal PART I How to Win the Nobel Prize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unrestricted Immigration and the Foreign Dominance Of

Unrestricted Immigration and the Foreign Dominance of United States Nobel Prize Winners in Science: Irrefutable Data and Exemplary Family Narratives—Backup Data and Information Andrew A. Beveridge, Queens and Graduate Center CUNY and Social Explorer, Inc. Lynn Caporale, Strategic Scientific Advisor and Author The following slides were presented at the recent meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. This project and paper is an outgrowth of that session, and will combine qualitative data on Nobel Prize Winners family histories along with analyses of the pattern of Nobel Winners. The first set of slides show some of the patterns so far found, and will be augmented for the formal paper. The second set of slides shows some examples of the Nobel families. The authors a developing a systematic data base of Nobel Winners (mainly US), their careers and their family histories. This turned out to be much more challenging than expected, since many winners do not emphasize their family origins in their own biographies or autobiographies or other commentary. Dr. Caporale has reached out to some laureates or their families to elicit that information. We plan to systematically compare the laureates to the population in the US at large, including immigrants and non‐immigrants at various periods. Outline of Presentation • A preliminary examination of the 609 Nobel Prize Winners, 291 of whom were at an American Institution when they received the Nobel in physics, chemistry or physiology and medicine • Will look at patterns of -

Steven Weinberg Cv Born

STEVEN WEINBERG CV BORN: May 3, 1933, in New York, N.Y. EDUCATION: Cornell University, 1950–1954 (A.B., 1954) Copenhagen Institute for Theoretical Physics, 1954–1955 Princeton University, 1955–1957 (Ph.D.,1957). HONORARY DEGREES: Harvard University, A.M., 1973 Knox College, D.Sc., 1978 University of Chicago, Sc.D., 1978 University of Rochester, Sc.D., l979 Yale University, Sc.D., 1979 City University of New York,Sc.D., 1980 Clark University, Sc.D., 1982 Dartmouth College, Sc.D., 1984 Weizmann Institute, Ph.D. Hon.Caus., 1985 Washington College, D.Litt., 1985 Columbia University, Sc.D., 1990 University of Salamanca, Sc.D., 1992 University of Padua, Ph.D. Hon.Caus., 1992 University of Barcelona, Sc.D., 1996 Bates College, Sc. D., 2002 McGill University, Sc. D., 2003 University of Waterloo, Sc. D., 2004 Renssalear Polytechnic Institue, Sc. D., 2016 Rockefeller University, Sc. D., 2017 PRESENT POSITION: Josey Regental Professor of Science, University of Texas, 1982– PAST POSITIONS: Columbia University, 1957–1959 Lawrence Radiation Laboratory, 1959–1960 University of California, Berkeley, 1960–1969 On leave, Imperial College, London, 1961–1962 Steven Weinberg 2 Became full professor, 1964 On leave, Harvard University, 1966–1967 On leave, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1967–1969 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1969–1973, Professor of Physics Harvard University, 1973–1983, Higgins Professor of Physics On leave 1976–1977, as Visiting Professor of Physics, Stanford University Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, 1973-1983, Senior -

Al-Nahl Volume 13 Number 3

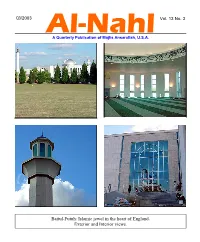

Q3/2003 Vol. 13 No. 3 Al-Nahl A Quarterly Publication of Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. Baitul-Futuh: Islamic jewel in the heart of England. Exterior and Interior views. Special Issue of the Al-Nahl on the Life of Hadrat Dr. Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, radiyallahu ‘anhu. 60 pages, $2. Special Issue on Dr. Abdus Salam. 220 pages, 42 color and B&W pictures, $3. Ansar Ansar (Ansarullah News) is published monthly by Majlis Ansarullah U.S.A. and is sent free of charge to all Ansar in the U.S. Ordering Information: Send a check or money order in the indicated amount along with your order to Chaudhary Mushtaq Ahmad, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring, MD 20905. Price includes shipping and handling within the continental U.S. Conditions of Bai‘at, Pocket-Size Edition Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. has published the ten conditions of initiation into the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in pocket size brochure. Contact your local officials for a free copy or write to Ansar Publications, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring MD 20905. Razzaq and Farida A story for children written by Dr. Yusef A. Lateef. Children and new Muslims, all can read and enjoy this story. It makes a great gift for the children of Ahmadi, Non-Ahmadi and Non- Muslim relatives, friends and acquaintances. The book contains colorful drawings. Please send $1.50 per copy to Chaudhary Mushtaq Ahmad, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring, MD 20905 with your mailing address and phone number. Majlis Ansarullah U.S.A. will pay the postage and handling within the continental U.S. -

Rutherford's Nuclear World: the Story of the Discovery of the Nuc

Rutherford's Nuclear World: The Story of the Discovery of the Nuc... http://www.aip.org/history/exhibits/rutherford/sections/atop-physic... HOME SECTIONS CREDITS EXHIBIT HALL ABOUT US rutherford's explore the atom learn more more history of learn about aip's nuclear world with rutherford about this site physics exhibits history programs Atop the Physics Wave ShareShareShareShareShareMore 9 RUTHERFORD BACK IN CAMBRIDGE, 1919–1937 Sections ← Prev 1 2 3 4 5 Next → In 1962, John Cockcroft (1897–1967) reflected back on the “Miraculous Year” ( Annus mirabilis ) of 1932 in the Cavendish Laboratory: “One month it was the neutron, another month the transmutation of the light elements; in another the creation of radiation of matter in the form of pairs of positive and negative electrons was made visible to us by Professor Blackett's cloud chamber, with its tracks curled some to the left and some to the right by powerful magnetic fields.” Rutherford reigned over the Cavendish Lab from 1919 until his death in 1937. The Cavendish Lab in the 1920s and 30s is often cited as the beginning of modern “big science.” Dozens of researchers worked in teams on interrelated problems. Yet much of the work there used simple, inexpensive devices — the sort of thing Rutherford is famous for. And the lab had many competitors: in Paris, Berlin, and even in the U.S. Rutherford became Cavendish Professor and director of the Cavendish Laboratory in 1919, following the It is tempting to simplify a complicated story. Rutherford directed the Cavendish Lab footsteps of J.J. Thomson. Rutherford died in 1937, having led a first wave of discovery of the atom. -

Arthur S. Eddington the Nature of the Physical World

Arthur S. Eddington The Nature of the Physical World Arthur S. Eddington The Nature of the Physical World Gifford Lectures of 1927: An Annotated Edition Annotated and Introduced By H. G. Callaway Arthur S. Eddington, The Nature of the Physical World: Gifford Lectures of 1927: An Annotated Edition, by H. G. Callaway This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by H. G. Callaway All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-6386-6, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-6386-5 CONTENTS Note to the Text ............................................................................... vii Eddington’s Preface ......................................................................... ix A. S. Eddington, Physics and Philosophy .......................................xiii Eddington’s Introduction ................................................................... 1 Chapter I .......................................................................................... 11 The Downfall of Classical Physics Chapter II ......................................................................................... 31 Relativity Chapter III -

Einstein's Mistakes

Einstein’s Mistakes Einstein was the greatest genius of the Twentieth Century, but his discoveries were blighted with mistakes. The Human Failing of Genius. 1 PART 1 An evaluation of the man Here, Einstein grows up, his thinking evolves, and many quotations from him are listed. Albert Einstein (1879-1955) Einstein at 14 Einstein at 26 Einstein at 42 3 Albert Einstein (1879-1955) Einstein at age 61 (1940) 4 Albert Einstein (1879-1955) Born in Ulm, Swabian region of Southern Germany. From a Jewish merchant family. Had a sister Maja. Family rejected Jewish customs. Did not inherit any mathematical talent. Inherited stubbornness, Inherited a roguish sense of humor, An inclination to mysticism, And a habit of grüblen or protracted, agonizing “brooding” over whatever was on its mind. Leading to the thought experiment. 5 Portrait in 1947 – age 68, and his habit of agonizing brooding over whatever was on its mind. He was in Princeton, NJ, USA. 6 Einstein the mystic •“Everyone who is seriously involved in pursuit of science becomes convinced that a spirit is manifest in the laws of the universe, one that is vastly superior to that of man..” •“When I assess a theory, I ask myself, if I was God, would I have arranged the universe that way?” •His roguish sense of humor was always there. •When asked what will be his reactions to observational evidence against the bending of light predicted by his general theory of relativity, he said: •”Then I would feel sorry for the Good Lord. The theory is correct anyway.” 7 Einstein: Mathematics •More quotations from Einstein: •“How it is possible that mathematics, a product of human thought that is independent of experience, fits so excellently the objects of physical reality?” •Questions asked by many people and Einstein: •“Is God a mathematician?” •His conclusion: •“ The Lord is cunning, but not malicious.” 8 Einstein the Stubborn Mystic “What interests me is whether God had any choice in the creation of the world” Some broadcasters expunged the comment from the soundtrack because they thought it was blasphemous. -

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

A Singing, Dancing Universe Jon Butterworth Enjoys a Celebration of Mathematics-Led Theoretical Physics

SPRING BOOKS COMMENT under physicist and Nobel laureate William to the intensely scrutinized narrative on the discovery “may turn out to be the greatest Henry Bragg, studying small mol ecules such double helix itself, he clarifies key issues. He development in the field of molecular genet- as tartaric acid. Moving to the University points out that the infamous conflict between ics in recent years”. And, on occasion, the of Leeds, UK, in 1928, Astbury probed the Wilkins and chemist Rosalind Franklin arose scope is too broad. The tragic figure of Nikolai structure of biological fibres such as hair. His from actions of John Randall, head of the Vavilov, the great Soviet plant geneticist of the colleague Florence Bell took the first X-ray biophysics unit at King’s College London. He early twentieth century who perished in the diffraction photographs of DNA, leading to implied to Franklin that she would take over Gulag, features prominently, but I am not sure the “pile of pennies” model (W. T. Astbury Wilkins’ work on DNA, yet gave Wilkins the how relevant his research is here. Yet pulling and F. O. Bell Nature 141, 747–748; 1938). impression she would be his assistant. Wilkins such figures into the limelight is partly what Her photos, plagued by technical limitations, conceded the DNA work to Franklin, and distinguishes Williams’s book from others. were fuzzy. But in 1951, Astbury’s lab pro- PhD student Raymond Gosling became her What of those others? Franklin Portugal duced a gem, by the rarely mentioned Elwyn assistant. It was Gosling who, under Franklin’s and Jack Cohen covered much the same Beighton. -

Urdu Syllabus

TUMKUR UINIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF URDU'. SYLLABUS AND TEXT BOOKS UNDER CBCS SCHEME LANGUAGE URDU lst Semester B.A./llsc/B.com/BBM/BCA lffect From 20!6-tz lst Semester B.A. Svllabus: Texts: I' 1. Collection of Prose and Poetry Urdu Language Text Book for First Semister B.A.: Edited by: URDU BOS (UG) (Printed and Published by prasaranga, Bangarore university, Bangalore) 2. Non-detail : Selected 4 Chapters From Text Book Reference Books: 1. Yadgaray Hali Saleha Aabid Hussain 2. lqbal Ka Narang QopiChandt 'i Page 1 z' i!. .F}*$T g_€.9f.*g.,,,E B'A BE$BEE CBU R$E Eenlcprqrerlh'ed:.Ufifi9 TFXT B €KeCn e,A I SEMESTER, : ,1 1;5:. -ll-=-- -i- - 1. padiye Gar Bcemar. 'M,tr*hf ag:A.hmgd-$tib.uf i 1.,gglrEdnre:a E*yl{arsfrt$ay Khwaja Hasan Nizarni 3" M_ugalrnanen Ki GurashthaTaleem Shibll Nomani +. lfilopatra N+y,Ek Moti €hola Sclence Ki Duniya : 5. g,€land:|4i$ ..- Manarir,Aashiq flarganvi PelfTR.Y i X., Hazrathfsmail Ki Viladat .FJafeez,J*lan*ari Naath 2. Hsli Mir.*e6halib 3. lqbal 4. T*j &Iahat 5*-e-ubipe.t{i Saher Ludhianawi ,,, lqbal, Amjad, Akbar {Z Eaehf 6g'**e€{F} i ': 1.. 6azaf W*& 2;1 ' 66;*; JaB:Flis,qf'*kfiit" 4., : €*itrl $hmed Fara:, 4. €azgl Firaq ,5; *- ,Elajrooh 6, Gqzal Shahqr..Y.aar' V. Gazal tiiarnsp{.4i1sruu ' 8. Gaal Narir Kqgrnt NG$I.SE.f*IL.: 1- : .*akF*!h*s ,&ri*an Ch*lrdar; 3. $alartrf,;oat &jendar.Sixgir.Ee t 3-, llfar*€,Ffate Tariq.€-hil*ari 4',,&alandar t'- €hig*lrl*tn:Ftyder' Ah*|.,9 . -

Patrick Blackett: Sailor, Scientist, Socialist, Chris Eldridge

Naval War College Review Volume 57 Article 31 Number 1 Winter 2004 Patrick Blackett: Sailor, Scientist, Socialist, Chris Eldridge Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Eldridge, Chris (2004) "Patrick Blackett: Sailor, Scientist, Socialist,," Naval War College Review: Vol. 57 : No. 1 , Article 31. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol57/iss1/31 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 156 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REVIEW Eldridge: Patrick Blackett: Sailor, Scientist, Socialist, understanding with the Soviet Union (a he was the heart and soul of the Cold position favored by some influential War military-academic-industrial com- opinions in the United States) nor to cre- plex. In this book, sixteen authors at- ate trouble for the French government, tempt to shed light on Blackett’s role in seemingly both dependent on and threat- that story. The collection includes pa- ened by the French Communist Party. pers presented at a 1998 conference The Soviet-menace card was played on commemorating Blackett at Cambridge several occasions in the unfolding de- University, as well as other recent writ- bate, but in general it was subordinated ings about him. to more abstract arguments of enlight- Not surprisingly, the compendium of- ened self-interest. Moreover, it was fers a range of perspectives on events clear to many in the administration that and issues with which Blackett was as- too great an emphasis on the immi- sociated, rather than a comprehensive nence of war with Russia would scuttle examination of his life and work. -

SHELDON LEE GLASHOW Lyman Laboratory of Physics Harvard University Cambridge, Mass., USA

TOWARDS A UNIFIED THEORY - THREADS IN A TAPESTRY Nobel Lecture, 8 December, 1979 by SHELDON LEE GLASHOW Lyman Laboratory of Physics Harvard University Cambridge, Mass., USA INTRODUCTION In 1956, when I began doing theoretical physics, the study of elementary particles was like a patchwork quilt. Electrodynamics, weak interactions, and strong interactions were clearly separate disciplines, separately taught and separately studied. There was no coherent theory that described them all. Developments such as the observation of parity violation, the successes of quantum electrodynamics, the discovery of hadron resonances and the appearance of strangeness were well-defined parts of the picture, but they could not be easily fitted together. Things have changed. Today we have what has been called a “standard theory” of elementary particle physics in which strong, weak, and electro- magnetic interactions all arise from a local symmetry principle. It is, in a sense, a complete and apparently correct theory, offering a qualitative description of all particle phenomena and precise quantitative predictions in many instances. There is no experimental data that contradicts the theory. In principle, if not yet in practice, all experimental data can be expressed in terms of a small number of “fundamental” masses and cou- pling constants. The theory we now have is an integral work of art: the patchwork quilt has become a tapestry. Tapestries are made by many artisans working together. The contribu- tions of separate workers cannot be discerned in the completed work, and the loose and false threads have been covered over. So it is in our picture of particle physics. Part of the picture is the unification of weak and electromagnetic interactions and the prediction of neutral currents, now being celebrated by the award of the Nobel Prize. -

The Nobel Prize in Physics: Four Historical Case Studies

The Nobel Prize in Physics: Four Historical Case Studies By: Hannah Pell, Research Assistant November 2019 From left: Arnold Sommerfeld, Lise Meitner, Chien-Shiung Wu, Satyendra Nath Bose. Images courtesy of the AIP Emilio Segré Visual Archives. Grade Level(s): 11-12, College Subject(s): History, Physics In-Class Time: 50 - 60 minutes Prep Time: 15 – 20 minutes Materials • Photocopies of case studies (found in the Supplemental Materials) • Student internet access Objective Students will investigate four historical case studies of physicists who some physicists and historians have argued should have won a Nobel Prize in physics: Arnold Sommerfeld, Lise Meitner, Chien-Shiung Wu, and Satyendra Nath Bose. With each Case Study, students examine the historical context surrounding the prize that year (if applicable) as well as potential biases inherent in the structure of the Nobel Prize committee and its selection process. Students will summarize arguments for why these four physicists should have been awarded a Nobel Prize, as well as potential explanations for why they were not awarded the honor. Introduction Introduction to the Nobel Prize In 1895, Alfred Nobel—a Swedish chemist and engineer who invented dynamite—signed into his will that a large portion of his vast fortune should be used to create a series of annual prizes awarded to those who “confer the greatest benefit on mankind” in physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, 1 literature, and peace.1 (The Nobel Prize in economics was added later to the collection of disciplines in 1968). Thus, the Nobel Foundation was founded as a private organization in 1900 and the first Nobel Prizes were awarded in 1901.