The Creation of the International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Trieste

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navigazioni Possibili: Italies Lost and Found

10th ACIS Biennial Conference Victoria University of Wellington 7 – 10 February 2019 Navigazioni possibili: Italies Lost and Found Conference Programme We would like to thank the following organisations for their support: We are also grateful to: Book exhibition by: Catering by: And a very special thank you to: Lagi Aukusitino, Russell Bryant-Fischer, Nina Cuccurullo, Karen Foote, Ida Li, Lisa Lowe, Rory McKenzie, Caroline Nebel, Anton Pagalilawan, Marco Sonzogni, Paddy Twigg 2 Table of Contents General Information ............................................................................................................................... 4 Emergency Instructions .......................................................................................................................... 5 Guide to conference locations ................................................................................................................ 6 Kelburn Campus Map .............................................................................................................................. 7 Pipitea Campus Map ............................................................................................................................... 8 Pōwhiri .................................................................................................................................................... 9 Conference Program ............................................................................................................................. 10 Keynote presentations -

Camilla Da Dalt, the Case of Morpurgo De Nilma's Art Collection in Trieste

STUDI DI MEMOFONTE Rivista on-line semestrale Numero 22/2019 FONDAZIONE MEMOFONTE Studio per l’elaborazione informatica delle fonti storico-artistiche www.memofonte.it COMITATO REDAZIONALE Proprietario Fondazione Memofonte onlus Fondatrice Paola Barocchi Direzione scientifica Donata Levi Comitato scientifico Francesco Caglioti, Barbara Cinelli, Flavio Fergonzi, Margaret Haines, Donata Levi, Nicoletta Maraschio, Carmelo Occhipinti Cura scientifica Daria Brasca, Christian Fuhrmeister, Emanuele Pellegrini Cura redazionale Martina Nastasi, Laurence Connell Segreteria di redazione Fondazione Memofonte onlus, via de’ Coverelli 2/4, 50125 Firenze [email protected] ISSN 2038-0488 INDICE The Transfer of Jewish-owned Cultural Objects in the Alpe Adria Region DARIA BRASCA, CHRISTIAN FUHRMEISTER, EMANUELE PELLEGRINI Introduction p. 1 VICTORIA REED Museum Acquisitions in the Era of the Washington Principles: Porcelain from the Emma Budge Estate p. 9 GISÈLE LÉVY Looting Jewish Heritage in the Alpe Adria Region. Findings from the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities (UCEI) Historical Archives p. 28 IVA PASINI TRŽEC Contentious Musealisation Process(es) of Jewish Art Collections in Croatia p. 41 DARIJA ALUJEVIĆ Jewish-owned Art Collections in Zagreb: The Destiny of the Robert Deutsch Maceljski Collection p. 50 ANTONIJA MLIKOTA The Destiny of the Tilla Durieux Collection after its Transfer from Berlin to Zagreb p. 64 DARIA BRASCA The Dispossession of Italian Jews: the Fate of Cultural Property in the Alpe Adria Region during Second World War p. 79 CAMILLA DA DALT The Case of Morpurgo De Nilma’s Art Collection in Trieste: from a Jewish Legacy to a ‘German Donation’ p. 107 CRISTINA CUDICIO The Dissolution of a Jewish Collection: the Pincherle Family in Trieste p. -

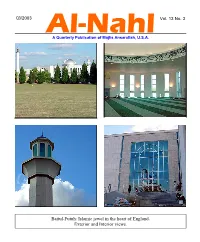

Al-Nahl Volume 13 Number 3

Q3/2003 Vol. 13 No. 3 Al-Nahl A Quarterly Publication of Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. Baitul-Futuh: Islamic jewel in the heart of England. Exterior and Interior views. Special Issue of the Al-Nahl on the Life of Hadrat Dr. Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, radiyallahu ‘anhu. 60 pages, $2. Special Issue on Dr. Abdus Salam. 220 pages, 42 color and B&W pictures, $3. Ansar Ansar (Ansarullah News) is published monthly by Majlis Ansarullah U.S.A. and is sent free of charge to all Ansar in the U.S. Ordering Information: Send a check or money order in the indicated amount along with your order to Chaudhary Mushtaq Ahmad, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring, MD 20905. Price includes shipping and handling within the continental U.S. Conditions of Bai‘at, Pocket-Size Edition Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. has published the ten conditions of initiation into the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in pocket size brochure. Contact your local officials for a free copy or write to Ansar Publications, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring MD 20905. Razzaq and Farida A story for children written by Dr. Yusef A. Lateef. Children and new Muslims, all can read and enjoy this story. It makes a great gift for the children of Ahmadi, Non-Ahmadi and Non- Muslim relatives, friends and acquaintances. The book contains colorful drawings. Please send $1.50 per copy to Chaudhary Mushtaq Ahmad, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring, MD 20905 with your mailing address and phone number. Majlis Ansarullah U.S.A. will pay the postage and handling within the continental U.S. -

Urdu Syllabus

TUMKUR UINIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF URDU'. SYLLABUS AND TEXT BOOKS UNDER CBCS SCHEME LANGUAGE URDU lst Semester B.A./llsc/B.com/BBM/BCA lffect From 20!6-tz lst Semester B.A. Svllabus: Texts: I' 1. Collection of Prose and Poetry Urdu Language Text Book for First Semister B.A.: Edited by: URDU BOS (UG) (Printed and Published by prasaranga, Bangarore university, Bangalore) 2. Non-detail : Selected 4 Chapters From Text Book Reference Books: 1. Yadgaray Hali Saleha Aabid Hussain 2. lqbal Ka Narang QopiChandt 'i Page 1 z' i!. .F}*$T g_€.9f.*g.,,,E B'A BE$BEE CBU R$E Eenlcprqrerlh'ed:.Ufifi9 TFXT B €KeCn e,A I SEMESTER, : ,1 1;5:. -ll-=-- -i- - 1. padiye Gar Bcemar. 'M,tr*hf ag:A.hmgd-$tib.uf i 1.,gglrEdnre:a E*yl{arsfrt$ay Khwaja Hasan Nizarni 3" M_ugalrnanen Ki GurashthaTaleem Shibll Nomani +. lfilopatra N+y,Ek Moti €hola Sclence Ki Duniya : 5. g,€land:|4i$ ..- Manarir,Aashiq flarganvi PelfTR.Y i X., Hazrathfsmail Ki Viladat .FJafeez,J*lan*ari Naath 2. Hsli Mir.*e6halib 3. lqbal 4. T*j &Iahat 5*-e-ubipe.t{i Saher Ludhianawi ,,, lqbal, Amjad, Akbar {Z Eaehf 6g'**e€{F} i ': 1.. 6azaf W*& 2;1 ' 66;*; JaB:Flis,qf'*kfiit" 4., : €*itrl $hmed Fara:, 4. €azgl Firaq ,5; *- ,Elajrooh 6, Gqzal Shahqr..Y.aar' V. Gazal tiiarnsp{.4i1sruu ' 8. Gaal Narir Kqgrnt NG$I.SE.f*IL.: 1- : .*akF*!h*s ,&ri*an Ch*lrdar; 3. $alartrf,;oat &jendar.Sixgir.Ee t 3-, llfar*€,Ffate Tariq.€-hil*ari 4',,&alandar t'- €hig*lrl*tn:Ftyder' Ah*|.,9 . -

1954, Addio Trieste... the Triestine Community of Melbourne

1954, Addio Trieste... The Triestine Community of Melbourne Adriana Nelli A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University November 2000 -^27 2->v<^, \U6IL THESIS 994.5100451 NEL 30001007178181 Ne 1 li, Adriana 1954, addio Trieste— the Triestine community of MeIbourne I DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the product of my original work, including all translations from Italian and Triestine. An earlier form of Chapter 5 appeared in Robert Pascoe and Jarlath Ronayne, eds, The passeggiata of Exile: The Italian Story in Australia (Victoria University, Melbourne, 1998). Parts of my argument also appeared in 'L'esperienza migratoria triestina: L'identita' culturale e i suoi cambiamenti' in Gianfranco Cresciani, ed., Giuliano-Dalmati in Australia: Contributi e testimonianze per una storia (Associazione Giuliani nel Mondo, Trieste, 1999). Adriana Nelli ABSTRACT Triestine migration to Australia is the direct consequence of numerous disputations over the city's political boundaries in the immediate post- World War II period. As such the triestini themselves are not simply part of an overall migratory movement of Italians who took advantage of Australia's post-war immigration program, but their migration is also the reflection of an important period in the history of what today is known as the Friuli Venezia Giulia Region.. 1954 marked the beginning of a brief but intense migratory flow from the city of Trieste towards Australia. Following a prolonged period of Anglo-American administration, the city had been returned to Italian jurisdiction once more; and with the dismantling of the Allied caretaker government and the subsequent economic integration of Trieste into the Italian State, a climate of uncertainty and precariousness had left the Triestines psychologically disenchanted and discouraged. -

A State of the Art Report on the Italo-Slovene Border

EUROREG Changing interests and identities in European border regions: A state of the art report on the Italo-Slovene border Jeremy Faro Kingston University United Kingdom INTERREG IIIA ITALY/SLOVENIA PROGRAMMING REGION 6th Framework Programme Priority 7: Citizens and Governance in Knowledge Based Society Contract no. FP6-506019 Table of Contents 1.0 The Italo-Slovene borderland: an introduction to the frontier, its population, and EU-led cross-border cooperation 1 2.0 An overview of Italo-Slovene borderland and minority relations, 1918-2004 2 2.1.1 The ethnicity and geography of the Italo-Slovene borderland, 1918-1945 2 2.1.2 The ethnicity and geography of the Italo-Slovene borderland, 1945-2004 6 2.1.3 Ethno-linguistic minority issues in the Italo-Slovene frontier, 1994-2005 12 2.2 Socio-economic development and EU regional policy in the Italo-Slovene borderland 14 2.3 The institutional geography of Italo-Slovene cross-border cooperation 17 2.4 Overall assessment 19 3.0 Literature review 20 3.1 An overview of the political economy and anthropology of borderlands 20 3.2 Ethnic-national identities and the politics of culture and identity: Typologies of borderland identity and development 23 3.3 Minority-majority relations in the borderland: Toward a theoretical context for cross-border cooperation 26 4.0 Conclusion 29 Bibliography 31 Annex I: Policy report 41 Annex II: Research competence mapping 50 1.0 The Italo-Slovene borderland: an introduction to the frontier, its population, and EU- led cross-border cooperation The ‘natural’ boundary between Italy and Slovenia—the summit line of the Julian Alps— arrives suddenly, just north of metropolitan Trieste, amidst the morphologically non-linear Karst: those classical, jagged limestone hills, caves, and pits created over millennia by underground rivers which have given their name to similar geological formations around the world. -

Origins and Early Years Peace Through Scientific Co-Operation Became an Abiding Purpose

Topical reports: 30th anniversary year The International Atomic Energy Agency: Origins and early years Peace through scientific co-operation became an abiding purpose by Dr John A. Hall Motivated by the apprehension of scientists and' Auspices of the United States Government 1940-1945.* statesmen, created by determined negotiating groups^ This lengthy title/prp'ved too cumbersome for some of and structured to meet thexchallenges of.the future, the the reviewers. The, account,,— prepared by Professor International Atomic Energy Agency celebrates its 30th Henry DeWolf Smyth, Chairman of the Department of birthday on 29 July 1987. • ~\ "' '.. - -">;; •Physics of Princeton University — presented concisely The concept of an international atomic energy organi- in language understandable to the layman, the scientific zation was proposed over 40 years ago. The aims ofsuch background and the nature of atomic energy, and the an organization were to control the new force of nuclear development of the weapon. This small book enjoyed energy for peaceful purposes, to solve the problem of extensive circulation and has been translated into 40 lan- atomic weapon limitation, to protect the public from the guages.** hazards of radiation, and also to promote a constructive dialogue between the United States and the Soviet Union Postwar roots in this new and dynamic field. Following the war, many scientists and statesmen had After the formulation of the early proposals, 10 years concluded that it was vital to secure international control of discussion and fumbling followed, finally resulting in of nuclear energy. The new United Nations, established negotiations leading to the establishment in 1957 of an in the summer of 1945, appeared to be the logical forum autonomous and independent international organization, for examining the possible ways of achieving this goal. -

May 17, 2014 Speech by Prof. Fernando Quevedo, Director of The

May 17, 2014 Speech by Prof. Fernando Quevedo, director of the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP ), on the occasion of the Premio Barcola 2014 ceremony Dear friends, Good morning. I would first like to thank the Barcola Award organizing committee for considering ICTP worthy of receiving a prize which in the past has recognized individuals and organizations who have given a lot to this city. In the next few minutes I would like to tell you what ICTP gave Trieste, but also how important it was for us to choose Trieste as the seat for our institution, and how the city has given us not only infrastructure and institutional support, but also hospitality and friendship. I like to call ICTP a unique model of international cooperation. ICTP is in fact the first, and remains the most important, global institution for research and education in the sciences. The Abdus Salam ICTP was founded with the help of Paolo Budinich in 1964, exactly 50 years ago, under the auspices of the Italian Government and the International Atomic Energy Agency. The research that led to Abdus Salam's Nobel Prize in 1979 was conducted in large part right here in Trieste . Since 1995, the administration of the ICTP has been handled by UNESCO, with a tripartite agreement in which Italy makes most of the financial contribution. Abdus Salam was not only one of the best physicists of the time, he was also a special person in many ways. Born in Pakistan (at the time a British colony), Salam had the good fortune to have his talent recognized from a young age. -

Fondazione Internazionale Trieste Per Il Progresso E La Libertà Delle Scienze and SISSA Interdisciplinary Laboratory

EUROPEAN CITY OF SCIENCE 2020 Freedom for Science, Science for Freedom 1 FREEDOM FOR SCIENCE, SCIENCE FOR FREEDOM Dear Dr. Tindemans I would like to express again the support of the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research – MIUR – to the candidature of Trieste to host the Euro Science Open forum (ESOF) in 2020. The candidature is solid and the proposed PROESOF2020 program, with the specifc goal of promoting discussion and deepening European scientifc collaboration ahead of the opening of ESOF is an unprecedented initiative represents an added value to the Valeria Fedeli proposal. Minister of Instruction, University and Research The motto “Freedom for Science, Science for Freedom”, is a refection of our times. Not only does it apply to the modern age, but it also provides guidance in the face of rapidly changing societies resulting from technological advancements and innovations, and Trieste, for it’s very well known high concentration of national and international Scientifc Institutions, functioning both as institutes of higher education as well as science and technology parks for high level research, and for both geographic and historical reasons, could not be a more ftting city to be named the European City of Science. Euro Science Open Forum would surely gain extra visibility and play an unprecedented role in the integration of Europe and in the relations between Europe and the Far-East and the South Mediterranean, and we believe that, with all its outreach and scientifc opportunities, ESOF 2020 would represent a milestone in Italy’ events to promote the role of science in society in a European context. -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof. -

Theory and Experiment in the Quantum-Relativity Revolution

Theory and Experiment in the Quantum-Relativity Revolution expanded version of lecture presented at American Physical Society meeting, 2/14/10 (Abraham Pais History of Physics Prize for 2009) by Stephen G. Brush* Abstract Does new scientific knowledge come from theory (whose predictions are confirmed by experiment) or from experiment (whose results are explained by theory)? Either can happen, depending on whether theory is ahead of experiment or experiment is ahead of theory at a particular time. In the first case, new theoretical hypotheses are made and their predictions are tested by experiments. But even when the predictions are successful, we can’t be sure that some other hypothesis might not have produced the same prediction. In the second case, as in a detective story, there are already enough facts, but several theories have failed to explain them. When a new hypothesis plausibly explains all of the facts, it may be quickly accepted before any further experiments are done. In the quantum-relativity revolution there are examples of both situations. Because of the two-stage development of both relativity (“special,” then “general”) and quantum theory (“old,” then “quantum mechanics”) in the period 1905-1930, we can make a double comparison of acceptance by prediction and by explanation. A curious anti- symmetry is revealed and discussed. _____________ *Distinguished University Professor (Emeritus) of the History of Science, University of Maryland. Home address: 108 Meadowlark Terrace, Glen Mills, PA 19342. Comments welcome. 1 “Science walks forward on two feet, namely theory and experiment. ... Sometimes it is only one foot which is put forward first, sometimes the other, but continuous progress is only made by the use of both – by theorizing and then testing, or by finding new relations in the process of experimenting and then bringing the theoretical foot up and pushing it on beyond, and so on in unending alterations.” Robert A. -

Mathematics People, Volume 51, Number 11

Mathematics People bestowed by the U.S. government on outstanding young Bjorken and Callan Awarded scientists, mathematicians, and engineers who are in the 2004 Dirac Medals early stages of establishing their independent research careers. The 2004 Dirac Medals of the Abdus Salam International Three scholars who work in the mathematical sciences Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) have been awarded were honored for 2003. They are KONSTANTINA TRIVISA, Uni- to JAMES D. BJORKEN of Stanford University and CURTIS G. versity of Maryland, College Park; RAVI VAKIL, Stanford Uni- CALLAN of Princeton University for their work in the use of versity; and HARRY DANKOWICZ, Virginia Polytechnic Institute deep inelastic scattering for shedding light on the nature and State University. of strong interactions. The recipients were selected from nominations made The award citation reads: “Bjorken was the first to re- by eight participating federal agencies. Each awardee re- alize the importance of deep inelastic scattering and the ceives a five-year grant ranging from $400,000 to nearly first to understand the scaling of cross sections, an insight $1 million to further his or her research and educational that ultimately bore his name—the Bjorken scaling of efforts. cross sections. Callan, together with Kurt Symanzik (now deceased), reinvented the perturbative renormalization —From an NSF announcement group (in a form that now bears the name Callan-Symanzik equations) and recognized these groups as measures of scale invariance anomalies. Callan has applied these tech- Prizes of the Académie des niques to analyses of deep inelastic scattering and has made substantial contributions to particle physics and, more Sciences recently, string theory.” The ICTP awarded its first Dirac Medal in 1985.