Towards an Encoding for North Indic Number Forms in the UCS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-Language Framework for Word Recognition and Spotting of Indic Scripts

Cross-language Framework for Word Recognition and Spotting of Indic Scripts aAyan Kumar Bhunia, bPartha Pratim Roy*, aAkash Mohta, cUmapada Pal aDept. of ECE, Institute of Engineering & Management, Kolkata, India bDept. of CSE, Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee India cCVPR Unit, Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, India bemail: [email protected], TEL: +91-1332-284816 Abstract Handwritten word recognition and spotting of low-resource scripts are difficult as sufficient training data is not available and it is often expensive for collecting data of such scripts. This paper presents a novel cross language platform for handwritten word recognition and spotting for such low-resource scripts where training is performed with a sufficiently large dataset of an available script (considered as source script) and testing is done on other scripts (considered as target script). Training with one source script and testing with another script to have a reasonable result is not easy in handwriting domain due to the complex nature of handwriting variability among scripts. Also it is difficult in mapping between source and target characters when they appear in cursive word images. The proposed Indic cross language framework exploits a large resource of dataset for training and uses it for recognizing and spotting text of other target scripts where sufficient amount of training data is not available. Since, Indic scripts are mostly written in 3 zones, namely, upper, middle and lower, we employ zone-wise character (or component) mapping for efficient learning purpose. The performance of our cross- language framework depends on the extent of similarity between the source and target scripts. -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

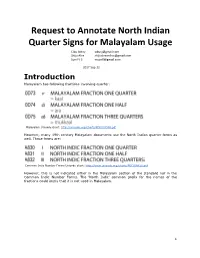

Request to Annotate North Indian Quarter Signs for Malayalam Usage Cibu Johny [email protected] Shiju Alex [email protected] Sunil V S [email protected]

Request to Annotate North Indian Quarter Signs for Malayalam Usage Cibu Johny [email protected] Shiju Alex [email protected] Sunil V S [email protected] 2017‐Sep‐22 Introduction Malayalam has following fractions involving quarter: Malayalam Unicode chart: h ttp://unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0D00.pdf However, many 19th century Malayalam documents use the North Indian quarter forms as well. Those forms are: Common Indic Number Forms Unicode chart: h ttp://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/UA830.pdf However, this is not indicated either in the Malayalam section of the standard nor in the Common Indic Number Forms. The ‘North Indic’ common prefix for the names of the fractions could imply that it is not used in Malayalam. 1 Attestations Attestations from various sources are listed below: 1856 The Malayalam Reader Charles Collet, CMS Press Cottayam, Page 4 1868 Kerala pazhama Basel Mission Press, Mangalore, Page 59 2 1873 Sreemahabharatham Vidyavilasam, Calicut, Cover page 1856 The Malayalam Reader Charles Collet, CMS Press Cottayam, Page 14,15 3 Annotation requests Request 1 The chart for Common Indic Number Forms needs to add following to U+A830, U+A830, and U+A830: ● Used in Malayalam also Request 2 The Malayalam chart should add following annotation: 0D73 ൳ MALAYALAM FRACTION ONE QUARTER → A830 ꠰ NORTH INDIC FRACTION ONE QUARTER 0D73 ൴ MALAYALAM FRACTION ONE HALF → A831 ꠱ NORTH INDIC FRACTION ONE HALF 0D73 ൵ MALAYALAM FRACTION THREE QUARTERS → A832 ꠲ NORTH INDIC FRACTION THREE QUARTERS Request 3 In section 12.9 Malayalam: Malayalam Numbers and Punctuation, following editorial change is required: Archaic Numbers. The characters used for the archaic number system, includes those for 10, 100, and 1000, and fractions. -

The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes

Portland State University PDXScholar Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Fariborz Maseeh Department of Mathematics Publications and Presentations and Statistics 3-2018 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hu Sun University of Macau Christine Chambris Université de Cergy-Pontoise Judy Sayers Stockholm University Man Keung Siu University of Hong Kong Jason Cooper Weizmann Institute of Science SeeFollow next this page and for additional additional works authors at: https:/ /pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Sun X.H. et al. (2018) The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes. In: Bartolini Bussi M., Sun X. (eds) Building the Foundation: Whole Numbers in the Primary Grades. New ICMI Study Series. Springer, Cham This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Authors Xu Hu Sun, Christine Chambris, Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper, Jean-Luc Dorier, Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued, Eva Thanheiser, Nadia Azrou, Lynn McGarvey, Catherine Houdement, and Lisser Rye Ejersbo This book chapter is available at PDXScholar: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac/253 Chapter 5 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hua Sun , Christine Chambris Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper , Jean-Luc Dorier , Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued , Eva Thanheiser , Nadia Azrou , Lynn McGarvey , Catherine Houdement , and Lisser Rye Ejersbo 5.1 Introduction Mathematics learning and teaching are deeply embedded in history, language and culture (e.g. -

Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe Romanization: KNAB 2012

Institute of the Estonian Language KNAB: Place Names Database 2012-10-11 Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe romanization: KNAB 2012 I. Consonant characters 1 ᦀ ’a 13 ᦌ sa 25 ᦘ pha 37 ᦤ da A 2 ᦁ a 14 ᦍ ya 26 ᦙ ma 38 ᦥ ba A 3 ᦂ k’a 15 ᦎ t’a 27 ᦚ f’a 39 ᦦ kw’a 4 ᦃ kh’a 16 ᦏ th’a 28 ᦛ v’a 40 ᦧ khw’a 5 ᦄ ng’a 17 ᦐ n’a 29 ᦜ l’a 41 ᦨ kwa 6 ᦅ ka 18 ᦑ ta 30 ᦝ fa 42 ᦩ khwa A 7 ᦆ kha 19 ᦒ tha 31 ᦞ va 43 ᦪ sw’a A A 8 ᦇ nga 20 ᦓ na 32 ᦟ la 44 ᦫ swa 9 ᦈ ts’a 21 ᦔ p’a 33 ᦠ h’a 45 ᧞ lae A 10 ᦉ s’a 22 ᦕ ph’a 34 ᦡ d’a 46 ᧟ laew A 11 ᦊ y’a 23 ᦖ m’a 35 ᦢ b’a 12 ᦋ tsa 24 ᦗ pa 36 ᦣ ha A Syllable-final forms of these characters: ᧅ -k, ᧂ -ng, ᧃ -n, ᧄ -m, ᧁ -u, ᧆ -d, ᧇ -b. See also Note D to Table II. II. Vowel characters (ᦀ stands for any consonant character) C 1 ᦀ a 6 ᦀᦴ u 11 ᦀᦹ ue 16 ᦀᦽ oi A 2 ᦰ ( ) 7 ᦵᦀ e 12 ᦵᦀᦲ oe 17 ᦀᦾ awy 3 ᦀᦱ aa 8 ᦶᦀ ae 13 ᦺᦀ ai 18 ᦀᦿ uei 4 ᦀᦲ i 9 ᦷᦀ o 14 ᦀᦻ aai 19 ᦀᧀ oei B D 5 ᦀᦳ ŭ,u 10 ᦀᦸ aw 15 ᦀᦼ ui A Indicates vowel shortness in the following cases: ᦀᦲᦰ ĭ [i], ᦵᦀᦰ ĕ [e], ᦶᦀᦰ ăe [ ∎ ], ᦷᦀᦰ ŏ [o], ᦀᦸᦰ ăw [ ], ᦀᦹᦰ ŭe [ ɯ ], ᦵᦀᦲᦰ ŏe [ ]. -

Inflectional Morphology Analyzer for Sanskrit

Inflectional Morphology Analyzer for Sanskrit Girish Nath Jha, Muktanand Agrawal, Subash, Sudhir K. Mishra, Diwakar Mani, Diwakar Mishra, Manji Bhadra, Surjit K. Singh [email protected] Special Centre for Sanskrit Studies Jawaharlal Nehru University New Delhi-110067 The paper describes a Sanskrit morphological analyzer that identifies and analyzes inflected noun- forms and verb-forms in any given sandhi-free text. The system which has been developed as java servlet RDBMS can be tested at http://sanskrit.jnu.ac.in (Language Processing Tools > Sanskrit Tinanta Analyzer/Subanta Analyzer) with Sanskrit data as unicode text. Subsequently, the separate systems of subanta and ti anta will be combined into a single system of sentence analysis with karaka interpretation. Currently, the system checks and labels each word as three basic POS categories - subanta, ti anta, and avyaya. Thereafter, each subanta is sent for subanta processing based on an example database and a rule database. The verbs are examined based on a database of verb roots and forms as well by reverse morphology based on Pāini an techniques. Future enhancements include plugging in the amarakosha ( http://sanskrit.jnu.ac.in/amara ) and other noun lexicons with the subanta system. The ti anta will be enhanced by the k danta analysis module being developed separately. 1. Introduction The authors in the present paper are describing the subanta and ti anta analysis systems for Sanskrit which are currently running at http://sanskrit.jnu.ac.in . Sanskrit is a heavily inflected language, and depends on nominal and verbal inflections for communication of meaning. A fully inflected unit is called pada . -

Sanskrit Translation Now Made, Be Crowned with Success ! PUBLISHER's NOTE

“KOHAM?” (Who am I ?) Sri Ramanasramam Tiruvannamalai - 606 603. 2008 Koham ? (Who am I ?) Published by V. S. Ramanan, President, Sri Ramanasramam, Tiruvannamalai - 606 603. Phone : 04175-237200 email : [email protected] Website : www.sriramanamaharshi.org © Sri Ramanasramam Tiruvannamalai. Salutations to Sri Ramana Who resides in the Heart Lotus PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION Many were the devotees who were attracted to the presence of Bhagavan Sri Ramana while he was living in the Virupaksha Cave, situated in the holy region of Arunachala, the Heart Centre of the world, which confers liberation on those who (merely) think of It. They were drawn to him on account of his wonderful state of tapas - absorption in the silence of yoga samadhi, which is difficult of achievement. One among these devotees was Sivaprakasam Pillai who approached Maharshi in 1901-02 with devotion, faith and humility and prayed that he may be blessed with instructions on Reality. The questions raised over a period of time by Sivaprakasam Pillai were answered by the silent Maharshi in writing - in Tamil. The compilation (of the instruction) in the form of questions and answers has already been translated into Malayalam and many other languages. May this Sanskrit translation now made, be crowned with success ! PUBLISHER'S NOTE The Sanskrit translation of Sri Bhagavan's Who am I ? entitled Koham? by Jagadiswara Sastry was published earlier in 1945. We are happy to bring out a second edition. The special feature of this edition is that the text is in Sri Bhagavan's handwriting. A transliteration of the text into English has also been provided. -

Vidyut Documentation

Vidyut A Phonetic Keyboard for Sanskrit Developers: Adolf von Württemberg ([email protected]) Les Morgan ([email protected]) Download: http://www.mywhatever.com/sanskrit/vidyut Current version: 5.0 (August 27, 2010) Requirements: Windows XP, Vista, Windows 7; 32-bit or 64-bit License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Vidyut Keyboard, Version 5 (Documentation as of 17 September 2010) Page 1 Contents Overview and Key Features ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Font Issues ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Installation instructions ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Typing Method ......................................................................................................................................................... 15 Customization ........................................................................................................................................................... 18 Keyboard Encoding Table (in Keyboard key order) ............................................................................................ 19 Keyboard Layout ..................................................................................................................................................... -

An Introduction to Indic Scripts

An Introduction to Indic Scripts Richard Ishida W3C [email protected] HTML version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.html PDF version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.pdf Introduction This paper provides an introduction to the major Indic scripts used on the Indian mainland. Those addressed in this paper include specifically Bengali, Devanagari, Gujarati, Gurmukhi, Kannada, Malayalam, Oriya, Tamil, and Telugu. I have used XHTML encoded in UTF-8 for the base version of this paper. Most of the XHTML file can be viewed if you are running Windows XP with all associated Indic font and rendering support, and the Arial Unicode MS font. For examples that require complex rendering in scripts not yet supported by this configuration, such as Bengali, Oriya, and Malayalam, I have used non- Unicode fonts supplied with Gamma's Unitype. To view all fonts as intended without the above you can view the PDF file whose URL is given above. Although the Indic scripts are often described as similar, there is a large amount of variation at the detailed implementation level. To provide a detailed account of how each Indic script implements particular features on a letter by letter basis would require too much time and space for the task at hand. Nevertheless, despite the detail variations, the basic mechanisms are to a large extent the same, and at the general level there is a great deal of similarity between these scripts. It is certainly possible to structure a discussion of the relevant features along the same lines for each of the scripts in the set. -

Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. & Dr. K. Muniratnam Director i/c, Epigraphy, ASI, Mysore Dr. Sayantani Pal Dept. of AIHC, University of Calcutta. Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Indian Epigraphy Module Name/Title Kharosthi Script Module Id IC / IEP / 15 Pre requisites Kharosthi Script – Characteristics – Origin – Objectives Different Theories – Distribution and its End Keywords E-text (Quadrant-I) : 1. Introduction Kharosthi was one of the major scripts of the Indian subcontinent in the early period. In the list of 64 scripts occurring in the Lalitavistara (3rd century CE), a text in Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit, Kharosthi comes second after Brahmi. Thus both of them were considered to be two major scripts of the Indian subcontinent. Both Kharosthi and Brahmi are first encountered in the edicts of Asoka in the 3rd century BCE. 2. Discovery of the script and its Decipherment The script was first discovered on one side of a large number of coins bearing Greek legends on the other side from the north western part of the Indian subcontinent in the first quarter of the 19th century. Later in 1830 to 1834 two full inscriptions of the time of Kanishka bearing the same script were found at Manikiyala in Pakistan. After this discovery James Prinsep named the script as ‘Bactrian Pehelevi’ since it occurred on a number of so called ‘Bactrian’ coins. To James Prinsep the characters first looked similar to Pahlavi (Semitic) characters. -

Simplified Abugidas

Simplified Abugidas Chenchen Ding, Masao Utiyama, and Eiichiro Sumita Advanced Translation Technology Laboratory, Advanced Speech Translation Research and Development Promotion Center, National Institute of Information and Communications Technology 3-5 Hikaridai, Seika-cho, Soraku-gun, Kyoto, 619-0289, Japan fchenchen.ding, mutiyama, [email protected] phonogram segmental abjad Abstract writing alphabet system An abugida is a writing system where the logogram syllabic abugida consonant letters represent syllables with Figure 1: Hierarchy of writing systems. a default vowel and other vowels are de- noted by diacritics. We investigate the fea- ណូ ន ណណន នួន ននន …ជិតណណន… sibility of recovering the original text writ- /noon/ /naen/ /nuən/ /nein/ vowel machine ten in an abugida after omitting subordi- diacritic omission learning ណន នន methods nate diacritics and merging consonant let- consonant character ters with similar phonetic values. This is merging N N … J T N N … crucial for developing more efficient in- (a) ABUGIDA SIMPLIFICATION (b) RECOVERY put methods by reducing the complexity in abugidas. Four abugidas in the south- Figure 2: Overview of the approach in this study. ern Brahmic family, i.e., Thai, Burmese, ters equally. In contrast, abjads (e.g., the Arabic Khmer, and Lao, were studied using a and Hebrew scripts) do not write most vowels ex- newswire 20; 000-sentence dataset. We plicitly. The third type, abugidas, also called al- compared the recovery performance of a phasyllabary, includes features from both segmen- support vector machine and an LSTM- tal and syllabic systems. In abugidas, consonant based recurrent neural network, finding letters represent syllables with a default vowel, that the abugida graphemes could be re- and other vowels are denoted by diacritics. -

The Formal Kharoṣṭhī Script from the Northern Tarim Basin in Northwest

Acta Orientalia Hung. 73 (2020) 3, 335–373 DOI: 10.1556/062.2020.00015 Th e Formal Kharoṣṭhī script from the Northern Tarim Basin in Northwest China may write an Iranian language1 FEDERICO DRAGONI, NIELS SCHOUBBEN and MICHAËL PEYROT* L eiden University Centre for Linguistics, Universiteit Leiden, Postbus 9515, 2300 RA Leiden, Th e Netherlands E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; *Corr esponding Author: [email protected] Received: February 13, 2020 •Accepted: May 25, 2020 © 2020 The Authors ABSTRACT Building on collaborative work with Stefan Baums, Ching Chao-jung, Hannes Fellner and Georges-Jean Pinault during a workshop at Leiden University in September 2019, tentative readings are presented from a manuscript folio (T II T 48) from the Northern Tarim Basin in Northwest China written in the thus far undeciphered Formal Kharoṣṭhī script. Unlike earlier scholarly proposals, the language of this folio can- not be Tocharian, nor can it be Sanskrit or Middle Indic (Gāndhārī). Instead, it is proposed that the folio is written in an Iranian language of the Khotanese-Tumšuqese type. Several readings are proposed, but a full transcription, let alone a full translation, is not possible at this point, and the results must consequently remain provisional. KEYWORDS Kharoṣṭhī, Formal Kharoṣṭhī, Khotanese, Tumšuqese, Iranian, Tarim Basin 1 We are grateful to Stefan Baums, Chams Bernard, Ching Chao-jung, Doug Hitch, Georges-Jean Pinault and Nicholas Sims-Williams for very helpful discussions and comments on an earlier draft. We also thank the two peer-reviewers of the manuscript. One of them, Richard Salomon, did not wish to remain anonymous, and espe- cially his observation on the possible relevance of Khotan Kharoṣṭhī has proved very useful.