The Impact of Visuo-Spatial Number Forms on Simple Arithmetic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

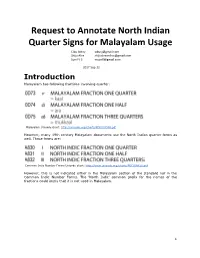

Request to Annotate North Indian Quarter Signs for Malayalam Usage Cibu Johny [email protected] Shiju Alex [email protected] Sunil V S [email protected]

Request to Annotate North Indian Quarter Signs for Malayalam Usage Cibu Johny [email protected] Shiju Alex [email protected] Sunil V S [email protected] 2017‐Sep‐22 Introduction Malayalam has following fractions involving quarter: Malayalam Unicode chart: h ttp://unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0D00.pdf However, many 19th century Malayalam documents use the North Indian quarter forms as well. Those forms are: Common Indic Number Forms Unicode chart: h ttp://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/UA830.pdf However, this is not indicated either in the Malayalam section of the standard nor in the Common Indic Number Forms. The ‘North Indic’ common prefix for the names of the fractions could imply that it is not used in Malayalam. 1 Attestations Attestations from various sources are listed below: 1856 The Malayalam Reader Charles Collet, CMS Press Cottayam, Page 4 1868 Kerala pazhama Basel Mission Press, Mangalore, Page 59 2 1873 Sreemahabharatham Vidyavilasam, Calicut, Cover page 1856 The Malayalam Reader Charles Collet, CMS Press Cottayam, Page 14,15 3 Annotation requests Request 1 The chart for Common Indic Number Forms needs to add following to U+A830, U+A830, and U+A830: ● Used in Malayalam also Request 2 The Malayalam chart should add following annotation: 0D73 ൳ MALAYALAM FRACTION ONE QUARTER → A830 ꠰ NORTH INDIC FRACTION ONE QUARTER 0D73 ൴ MALAYALAM FRACTION ONE HALF → A831 ꠱ NORTH INDIC FRACTION ONE HALF 0D73 ൵ MALAYALAM FRACTION THREE QUARTERS → A832 ꠲ NORTH INDIC FRACTION THREE QUARTERS Request 3 In section 12.9 Malayalam: Malayalam Numbers and Punctuation, following editorial change is required: Archaic Numbers. The characters used for the archaic number system, includes those for 10, 100, and 1000, and fractions. -

Letterlike Symbols Number Forms

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N2392 Title: A Report of Korean Script ad hoc group meeting on Oct. 15, 2001 Participants: Kim Kyongsok (ROK), Mun Hwang Ryong, Park Dong Ki, Yang Song Jin, Yun Chang Hwa (four from D P R of Korea), Kobayashi (not present when the report was written) Source : Korean script ad hoc group. Date: 2001-10-16 References: WG2 N2374, WG2 N2376, WG2 N2390, WG2 N2243 1. D P R of Korea nominated Mr. YANG, Song Jin as a co-chair from D P R of Korea. 2. Adding a 6th column to CJK and CJK Ext. A tables of ISO/IEC 10646-1:2000 [WG2 N2376] - D P R of Korea proposed that they would prepare a sample output of one page so that IRG and WG2 can review it, on the condition that IRG Rapporteur, IRG Technical Editor and Contributing Editor provide D P R of Korea with current CJK fonts and related software used to produce the current CJK tables. When the sample output proves acceptable, DPRK would prepare CJK and CJK Ext. A tables. - Detailed milestones can be discussed at WG2. 3. Adding 70 symbols [WG2 N2374, WG2 N2390] 3.1 For the following 47 characters, no issues were raised and propose that they be added to BMP. Letterlike Symbols Proposed Shape Character Name UCS LIMITED LIABILITY SIGN U+214C # 004C 0054 0044 PARTNERSHIP SIGN U+214D # 0050 0054 0045 FACSIMILE SIGN U+214E # 0046 0041 0058 Number Forms Proposed Shape Character Name UCS VULGAR FRACTION ONE HALF WITH U+2151 HORIZONTAL BAR # 00BD VULGAR FRACTION ONE THIRD WITH U+2184 HORIZONTAL BAR # 2153 VULGAR FRACTION TWO THIRDS WITH U+2185 HORIZONTAL BAR # 2154 VULGAR FRACTION -

Middle East-I 9 Modern and Liturgical Scripts

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

Number Forms Range: 2150–218F

Number Forms Range: 2150–218F This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Glossary of Mathematical Symbols

Glossary of mathematical symbols A mathematical symbol is a figure or a combination of figures that is used to represent a mathematical object, an action on mathematical objects, a relation between mathematical objects, or for structuring the other symbols that occur in a formula. As formulas are entirely constituted with symbols of various types, many symbols are needed for expressing all mathematics. The most basic symbols are the decimal digits (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9), and the letters of the Latin alphabet. The decimal digits are used for representing numbers through the Hindu–Arabic numeral system. Historically, upper-case letters were used for representing points in geometry, and lower-case letters were used for variables and constants. Letters are used for representing many other sort of mathematical objects. As the number of these sorts has dramatically increased in modern mathematics, the Greek alphabet and some Hebrew letters are also used. In mathematical formulas, the standard typeface is italic type for Latin letters and lower-case Greek letters, and upright type for upper case Greek letters. For having more symbols, other typefaces are also used, mainly boldface , script typeface (the lower-case script face is rarely used because of the possible confusion with the standard face), German fraktur , and blackboard bold (the other letters are rarely used in this face, or their use is unconventional). The use of Latin and Greek letters as symbols for denoting mathematical objects is not described in this article. For such uses, see Variable (mathematics) and List of mathematical constants. However, some symbols that are described here have the same shape as the letter from which they are derived, such as and . -

![Dejavusansmono-Bold.Ttf [Dejavu Sans Mono Bold]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5074/dejavusansmono-bold-ttf-dejavu-sans-mono-bold-3655074.webp)

Dejavusansmono-Bold.Ttf [Dejavu Sans Mono Bold]

DejaVuSerif.ttf [DejaVu Serif] [DejaVu Serif] Basic Latin, Latin-1 Supplement, Latin Extended-A, Latin Extended-B, IPA Extensions, Phonetic Extensions, Phonetic Extensions Supplement, Spacing Modifier Letters, Modifier Tone Letters, Combining Diacritical Marks, Combining Diacritical Marks Supplement, Greek And Coptic, Cyrillic, Cyrillic Supplement, Cyrillic Extended-A, Cyrillic Extended-B, Armenian, Thai, Georgian, Georgian Supplement, Latin Extended Additional, Latin Extended-C, Latin Extended-D, Greek Extended, General Punctuation, Supplemental Punctuation, Superscripts And Subscripts, Currency Symbols, Letterlike Symbols, Number Forms, Arrows, Supplemental Arrows-A, Supplemental Arrows-B, Miscellaneous Symbols and Arrows, Mathematical Operators, Supplemental Mathematical Operators, Miscellaneous Mathematical Symbols-A, Miscellaneous Mathematical Symbols-B, Miscellaneous Technical, Control Pictures, Box Drawing, Block Elements, Geometric Shapes, Miscellaneous Symbols, Dingbats, Non- Plane 0, Private Use Area (plane 0), Alphabetic Presentation Forms, Specials, Braille Patterns, Mathematical Alphanumeric Symbols, Variation Selectors, Variation Selectors Supplement DejaVuSansMono.ttf [DejaVu Sans Mono] [DejaVu Sans Mono] Basic Latin, Latin-1 Supplement, Latin Extended-A, Latin Extended-B, IPA Extensions, Phonetic Extensions, Phonetic Extensions Supplement, Spacing Modifier Letters, Modifier Tone Letters, Combining Diacritical Marks, Combining Diacritical Marks Supplement, Greek And Coptic, Cyrillic, Cyrillic Supplement, Cyrillic Extended-A, -

Junicode, V. 0.6.5

Junicode, v. 0.6.5 Table of Contents What is Junicode?...............................................................................................................2 GNU General Public License..............................................................................................3 How the GNU General Public License Applies to Junicode..............................................11 How to install Junicode.....................................................................................................12 1. Microsoft Windows..................................................................................................12 2. Macintosh OS X.......................................................................................................12 3. Linux.......................................................................................................................12 Reading the Code Charts..................................................................................................12 Basic Latin (0000-007F)....................................................................................................14 Latin 1 Supplement (0080-00FF)......................................................................................15 Latin Extended A (0100-017F).........................................................................................16 Latin Extended B (0180-024F).........................................................................................17 IPA Extensions (0250-02AF)............................................................................................18 -

Common Indic Number Forms Range: A830–A83F

Common Indic Number Forms Range: A830–A83F This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Proposal to Encode Ottoman Siyaq Numbers in Unicode

Proposal to encode Ottoman Siyaq Numbers in Unicode Anshuman Pandey [email protected] September 29, 2017 This is a proposal to encode Ottoman Siyaq Numbers in the Unicode standard. A description of the typology of the numbers and the encoding model have been presented in the following documents: • L2/07-414 “Proposal to Encode Siyaq Numerals” • L2/09-166 “Ottoman Numerals: Towards a Model for Encoding Numerals of the Siyaq Systems” • L2/11-271 “Preliminary Proposal to Encode Ottoman Siyaq Numbers in the UCS” • L2/15-072R2 “Proposal to Encode Ottoman Siyaq Numbers in Unicode” Major changes from previous versions are: • Removal of the alternate form of twenty thousand • Addition of two fractions and a description of their orthography Proposals to encode characters of three other Siyaq systems were submitted previously: • L2/15-066R “Proposal to Encode Diwani Siyaq Numbers in Unicode” • L2/15-121R2 “Proposal to Encode Indic Siyaq Numbers in Unicode” • L2/15-122R “Proposal to Encode Persian Siyaq Numbers in Unicode” 1 Script Details Block name The name ‘Ottoman Siyaq Numbers’ is assigned to the block. This name reflects the sources in which these numbers are most commonly attested. Character repertoire The proposed repertoire contains 61 characters. All distinctive characters are at- tested in the available sources, excerpts of which are enclosed here. Representative glyphs Representative glyphs are based upon numbers shown in the manuscript in figure 33. They reflect number forms found in the available sources. These glyphs resemble the metal type designs shown in Exposé des signes de numération usités chez les peuples orientaux anciens et modernes by Antoine Paulin Pihan (Paris: L’imprimerie impériale, 1860), see figures 29 and 30. -

Chapter 22, Symbols

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

AMD 22 to the First Edition of ISO/IEC 10646-1

© ISO/IEC FDAM for ISO/IEC 10646-1: 1993/Amd. 22: 1999 (E) Information technology — Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) — Part 1: Architecture and Basic Multilingual Plane AMENDMENT 22: Keyboard symbols 1. List of new character names 8A CIRCLED TRIANGLE DOWN (break) 8B BROKEN CIRCLE WITH NORTH WEST Insert the following character name entries at the ARROW (escape) indicated positions in the tables of character names 8C UNDO SYMBOL identified below, replacing the existing entries which 96 DECIMAL SEPARATOR KEY SYMBOL read “(This position shall not be used)”. 97 PREVIOUS PAGE Page 91. Table 38 - Row 21: LETTERLIKE 98 NEXT PAGE SYMBOLS, NUMBER FORMS 99 PRINT SCREEN SYMBOL 9A CLEAR SCREEN SYMBOL hex Name 39 INFORMATION SOURCE Page 101. Table 43 - Row 24: CONTROL PICTURES, OPTICAL CHARACTER RECOGNITION Page 93. Table 39 - Row 21: ARROWS hex Name hex Name 25 SYMBOL FOR DELETE FORM TWO EB UPWARDS WHITE ARROW ON PEDESTAL EC UPWARDS WHITE ARROW ON PEDESTAL WITH HORIZONTAL BAR Page 107. Table 46 - Row 25: BLOCK ELEMENTS, ED UPWARDS WHITE ARROW ON PEDESTAL GEOMETRIC SHAPES WITH VERTICAL BAR EE UPWARDS WHITE DOUBLE ARROW hex Name EF UPWARDS WHITE DOUBLE ARROW ON F0 WHITE SQUARE WITH UPPER LEFT PEDESTAL QUADRANT F0 RIGHTWARDS WHITE ARROW FROM WALL F1 WHITE SQUARE WITH LOWER LEFT F1 NORTH WEST ARROW TO CORNER QUADRANT F2 SOUTH EAST ARROW TO CORNER F2 WHITE SQUARE WITH LOWER RIGHT F3 UP DOWN WHITE ARROW QUADRANT F3 WHITE SQUARE WITH UPPER RIGHT QUADRANT Page 99. Table 42 - Row 23: MISCELLANEOUS F4 WHITE CIRCLE WITH UPPER LEFT TECHNICAL QUADRANT hex Name F5 WHITE CIRCLE WITH LOWER LEFT 80 INSERTION SYMBOL QUADRANT 81 CONTINUOUS UNDERLINE SYMBOL F6 WHITE CIRCLE WITH LOWER RIGHT 82 DISCONTINUOUS UNDERLINE SYMBOL QUADRANT 83 EMPHASIS SYMBOL F7 WHITE CIRCLE WITH UPPER RIGHT 84 COMPOSITION SYMBOL QUADRANT 85 WHITE SQUARE WITH CENTRE VERTICAL LINE 86 ENTER SYMBOL 87 ALTERNATIVE KEY SYMBOL 88 HELM SYMBOL 89 CIRCLED HORIZONTAL BAR WITH NOTCH (pause) 1 FDAM for ISO/IEC 10646-1: 1993/Amd.