Chapter 4 Relative Stabilities of Pyrochlore (A2 B2 O7 ), Disordered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract Spectroscopic Characterization of Fluorite

ABSTRACT SPECTROSCOPIC CHARACTERIZATION OF FLUORITE: RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN TRACE ELEMENT ZONING, DEFECTS AND COLOR By Carrie Wright This thesis consists of two separate papers on color in fluorite. In the first paper, synthetic fluorites doped with various REEs (10-300 ppm) were analyzed using direct current plasma spectrometry, optical absorption spectroscopy, fluorescence spectrophotometry, and electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy before and after receiving 10-25 Mrad of 60Co gamma irradiation. The combined results of these techniques indicate that the irradiation-induced color of the Y-, Gd-, La- and Ce-doped samples are the result of a REE-associated fluorine vacancy that traps two electrons. Divalent samarium may be the cause of the irradiation-induced green color of the Sm- doped sample. In the second paper, fluorite crystals from Bingham, NM, Long Lake, NY, and Westmoreland, NH were similarly investigated to determine the relationship between sectorally zoned trace elements, defects, and color. The results indicate causes of color similar to those in the synthetic samples with the addition of simple F-centers. SPECTROSCOPIC CHARACTERIZATION OF FLUORITE: RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN TRACE ELEMENT ZONING, DEFECTS AND COLOR A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University In partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Geology By Carrie Wright Miami University Oxford, OH 2002 Advisor_____________________ Dr. John Rakovan Reader______________________ Dr. Hailiang Dong TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction to the cause of color in fluorite 1 Manuscript 1-Chapter 2 29 “Spectroscopic investigation of lanthanide doped CaF2 crystals: implications for the cause of color” Manuscript 2-Chapter 3 95 “Spectroscopic characterization of fluorite from Bingham, NM, Long Lake, NY and Westmoreland, NH: relationships between trace element zoning, defects and color ii TABLE OF FIGURES Chapter 1 Figures 21 Figure 1a. -

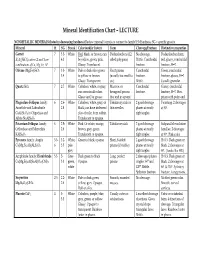

Mineral Identification Chart – LECTURE

Mineral Identification Chart – LECTURE NONMETALLIC MINERALS (listed in decreasing hardness) Review mineral formula to connect to family! H=Hardness; SG = specific gravity Mineral H SG Streak Color (and/or luster) Form Cleavage/Fracture Distinctive properties Garnet 7 3.5- White Red, black, or brown; can Dodecahedrons (12- No cleavage. Dodecahedron form, X3Y2(SiO4)3 where X and Y are 4.3 be yellow, green, pink. sided polygons) Brittle. Conchoidal red, glassy, conchoidal combinations of Ca, Mg, Fe, Al Glassy. Translucent. fracture. fracture, H=7. Olivine (Mg,Fe)2SiO4 7 3.3- White Pale or dark olive green Short prisms Conchoidal Green, conchoidal 3.4 to yellow or brown. (usually too small to fracture. fracture, glassy, H=7. Glassy. Transparent. see). Brittle. Usually granular. Quartz SiO2 7 2.7 White Colorless, white, or gray; Massive; or Conchoidal Glassy, conchoidal can occur in all colors. hexagonal prisms fracture. fracture, H=7. Hex. Glassy and/or greasy. that end in a point. prism with point end. Plagioclase Feldspar family: 6 2.6- White Colorless, white, gray, or Tabular crystals or 2 good cleavage Twinning. 2 cleavages Anorthite and Labradorite 2.8 black; can have iridescent thin needles planes at nearly at 90°. CaAl2Si2O8 to Oligoclase and play of color from within. right angles. Albite NaAlSi3O8 Translucent to opaque. Potassium Feldspar family: 6 2.5- White Pink. Or white, orange, Tabular crystals 2 good cleavage Subparallel exsolution Orthoclase and Microcline 2.6 brown, gray, green. planes at nearly lamellae. 2 cleavages KAlSi3O8 Translucent to opaque. right angles. at 90°. Pink color. Pyroxene family: Augite 5.5- 3.2- White, Green to black; opaque. -

Winter 1998 Gems & Gemology

WINTER 1998 VOLUME 34 NO. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 243 LETTERS FEATURE ARTICLES 246 Characterizing Natural-Color Type IIb Blue Diamonds John M. King, Thomas M. Moses, James E. Shigley, Christopher M. Welbourn, Simon C. Lawson, and Martin Cooper pg. 247 270 Fingerprinting of Two Diamonds Cut from the Same Rough Ichiro Sunagawa, Toshikazu Yasuda, and Hideaki Fukushima NOTES AND NEW TECHNIQUES 281 Barite Inclusions in Fluorite John I. Koivula and Shane Elen pg. 271 REGULAR FEATURES 284 Gem Trade Lab Notes 290 Gem News 303 Book Reviews 306 Gemological Abstracts 314 1998 Index pg. 281 pg. 298 ABOUT THE COVER: Blue diamonds are among the rarest and most highly valued of gemstones. The lead article in this issue examines the history, sources, and gemological characteristics of these diamonds, as well as their distinctive color appearance. Rela- tionships between their color, clarity, and other properties were derived from hundreds of samples—including such famous blue diamonds as the Hope and the Blue Heart (or Unzue Blue)—that were studied at the GIA Gem Trade Laboratory over the past several years. The diamonds shown here range from 0.69 to 2.03 ct. Photo © Harold & Erica Van Pelt––Photographers, Los Angeles, California. Color separations for Gems & Gemology are by Pacific Color, Carlsbad, California. Printing is by Fry Communications, Inc., Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania. © 1998 Gemological Institute of America All rights reserved. ISSN 0016-626X GIA “Cut” Report Flawed? The long-awaited GIA report on the ray-tracing analysis of round brilliant diamonds appeared in the Fall 1998 Gems & Gemology (“Modeling the Appearance of the Round Brilliant Cut Diamond: An Analysis of Brilliance,” by T. -

Mineralogy and Chemistry of Rare Earth Elements in Alkaline Ultramafic Rocks and Fluorite in the Western Kentucky Fluorspar District Warren H

Mineralogy and Chemistry of Rare Earth Elements in Alkaline Ultramafic Rocks and Fluorite in the Western Kentucky Fluorspar District Warren H. Anderson Report of Investigations 8 doi.org/10.13023/kgs.ri08.13 Series XIII, 2019 Cover Photo: Various alkaline ultramafic rocks showing porphyritic, brecciated, and aphanitic textures, in contact with host limestone and altered dike texture. From left to right: • Davidson North dike, Davidson core, YH-04, 800 ft depth. Lamprophyre with calcite veins, containing abundant rutile. • Coefield area, Billiton Minner core BMN 3. Intrusive breccia with lamprophyric (al- nöite) matrix. • Maple Lake area, core ML-1, 416 ft depth. Lamprophyre intrusive. • Maple Lake area, core ML-2, 513 ft depth. Lamprophyre (bottom) in contact with host limestone (top). Kentucky Geological Survey University of Kentucky, Lexington Mineralogy and Chemistry of Rare Earth Elements in Alkaline Ultramafic Rocks and Fluorite in the Western Kentucky Fluorspar District Warren H. Anderson Report of Investigations 8 doi.org/10.13023/kgs.ri08.13 Series XIII, 2019 Our Mission The Kentucky Geological Survey is a state-supported research center and public resource within the University of Kentucky. Our mission is to sup- port sustainable prosperity of the commonwealth, the vitality of its flagship university, and the welfare of its people. We do this by conducting research and providing unbiased information about geologic resources, environmen- tal issues, and natural hazards affecting Kentucky. Earth Resources—Our Common Wealth www.uky.edu/kgs © 2019 University of Kentucky For further information contact: Technology Transfer Officer Kentucky Geological Survey 228 Mining and Mineral Resources Building University of Kentucky Lexington, KY 40506-0107 Technical Level General Intermediate Technical Statement of Benefit to Kentucky Rare earth elements are used in many applications in modern society, from cellphones to smart weapons systems. -

Andradite in Andradite Unusual Growth Zoning in Beryl

Editor Nathan Renfro Contributing Editors Elise A. Skalwold and John I. Koivula Andradite in Andradite ity, but size was not what made it special. As shown in fig- Recently we had the opportunity to examine a dramatic ure 1, close examination of one of the polished crystal faces iridescent andradite fashioned by Falk Burger (Hard Works, revealed a bright reddish orange “hot spot” in the center, Tucson, Arizona) from a crystal originating from the caused by an iridescent inclusion of andradite with a dif- Tenkawa area of Nara Prefecture in Japan. Known as “rain- ferent crystallographic orientation than its host. As seen bow” andradite, this material was previously reported in in figure 2, the inclusion’s different orientation caused the iridescence of the rhomb-shaped “hot spot” to appear and Gems & Gemology (T. Hainschwang and F. Notari, “The cause of iridescence in rainbow andradite from Nara, disappear as the light source was passed over the crystal’s Japan,” Winter 2006, pp. 248–258). The specimen was surface. To see the iridescence from both the host and in- unique for its genesis and optical phenomenon. clusion at the same time, two light sources from opposite Weighing 16.79 ct and measuring 15.41 × 13.86 × 10.49 directions must be used due to the different crystallo- mm, the andradite was very large for its species and local- graphic orientation of the host and inclusion. This elusive optical phenomenon made this Japanese andradite crystal extremely interesting for any aspiring inclusionist. John I. Koivula Figure 1. This 16.79 ct Japanese andradite garnet GIA, Carlsbad exhibits a very unusual rhomb-shaped “hot spot” below the surface of one crystal face. -

The Eyes of Africa

The Eyes of Africa Where is it from? Erongo Mountain, Erongo Region, Namibia What are its dimensions? H: 22.8 in W: 13.3 in D: 10.2 in How much does it weight? 64.3 Pounds (29.2 kilos) What is this mineral made of? Fluorite & Quartz What is Fluorite (CaF2)? Named in 1797 by Carlo Antonio Galeani Napione from the Latin, fluere = “to flow” (for its use as a flux). The term fluores- cence is derived from fluorite, which will often markedly exhib- it this effect. The element fluorine also derives its name from fluorite. What is Quartz (SiO2)? Quartz has been known and appreciated since prehistoric times. Kristallos is the most ancient name known for quartz, recorded by Theophrastus in about 300-325 BCE. The root words κρύοσ (ice cold) and στέλλειυ (to contract) suggest the ancient belief that kristallos was permanently solidified ice. Brief Description: This specimen is known as “The Eyes of Africa.” It is composed of several white, semi-translucent quartz crystals and large, green and black Alien Eye Fluorites. It was recovered from the Erongo Region of Namibia in 2007. Alien Eyes are a unique and unusual subset of fluorite that differ- entiates itself with its vivid green color and black outer zones that create a diamond shape at each crystal’s center. They also have a naturally formed, complex crystal habit in the form of cuboctahedra. With light, Alien Eye fluorites glow with an incredible otherworldly quality which was what inspired their name. The total number of Alien Eye Fluorites recovered from the find is low, amounting to less than 30 fine specimens, due to the small pocket size and the fact that there was only one single discovery. -

1 Copyrighted Material

1 Crystals and crystal structures regular and beautiful shapes of naturally occur- What is a crystal system? ring crystals attracted attention from the ear- liest times, and the relationship between crystal What are unit cells? shape and the disposition of crystal faces, the crystal morphology, was soon used in classi- What information is needed to specify a fication. At a later stage in the development of crystal structure? the subject, symmetry, treated mathematically, became important in the description of crystals. The actual determination of crystal structures, the positions of all of the atoms in the crystal, was a Crystals are solids that possess long-range order. later level of refinement that was dependent upon The arrangement of the atoms at one point in a the discovery and subsequent use of X-rays. crystal is identical, (excepting localised mistakes or defects that can arise during crystal growth), to that in any other remote part of the crystal. Crystallography describes the ways in which 1.1 Crystal families and crystal systems the component atoms are arranged in crystals and how the long-range order is achieved. Many Careful measurement of mineral specimens chemical (including biochemical) and physical allowed crystals to be classified in terms of six properties depend on crystal structure and know- crystal families, called anorthic, monoclinic, ledge of crystallography is essential if the pro- orthorhombic, tetragonal, hexagonal and iso- perties of materials are to be understood and metric. This classification has been expanded exploited. slightly by crystallographers into seven crystal Crystallography first developed as an observa- systems. The crystal systems are sets of refer- tional science; an adjunct to the study of miner- ence axes, which have a direction as well as a 1 als. -

A Brief Overview Including Uses, Worldwide Resources, and Known Occurrences in Alaska

A brief overview including uses, worldwide resources, and known occurrences in Alaska Information Circular 61 David J. Szumigala and Melanie B. Werdon STATE OF ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys (DGGS) 3354 College Road, Fairbanks, AK 99709-3707 www.dggs.alaska.gov COVER PHOTO CAPTIONS: TOP: Sheeted REE-bearing veins, Dotson Trend, Bokan Mountain property, Alaska. Photo from http://www.ucoreraremetals.com/docs/SME_2010_Keyser.pdf BOTTOM: Rare-earth-element-bearing quartz vein exposed in granite, Bokan Mountain, Alaska. Photo from http://www.ucoreraremetals.com/docs/SME_2010_Keyser.pdf RARE-EARTH ELEMENTS: A brief overview including uses, worldwide resources, and known occurrences in Alaska David J. Szumigala and Melanie B. Werdon GGS Minerals Program The Alaska Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys (DGGS), part of the Department of Natural Resources, is charged by statute with determining the potential of Alaska’s land for production of metals, minerals, fuels, and geothermal resources; the locations and supplies of groundwater and construction Dmaterial; and the potential geologic hazards to buildings, roads, bridges, and other installations and structures. The Mineral Resources Section at DGGS collects, analyzes, and provides information on the geological and geophysical framework of Alaska as it pertains to the state’s mineral resources. The results of these studies include reports and maps, which are used by scientists for various associated studies, by mining company geologists as a basis for their more focused exploration programs, and by state and federal agency personnel in resource and land-use management decisions. This paper provides a brief overview of rare-earth elements, their uses, and current worldwide sources of their production. -

Calcite Measured Using Atomic Force Microscopy

Hindawi Journal of Chemistry Volume 2020, Article ID 3163415, 15 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3163415 Research Article The Interaction Force between Scheelite and Scheelite/Fluorite/ Calcite Measured Using Atomic Force Microscopy Junyan Yang ,1,2,3,4 Shen Qi ,1,3,4 Bo Song ,2 Qi Zheng ,1,3,4 Xiaokui Che ,1,3,4 and Lijun Wang 1,3,4 1National Engineering Laboratory of Biohydrometallurgy, GRINM Group Corp., Ltd., Beijing 100088, China 2School of Metallurgical and Ecological Engineering, University of Science and Technology Beijing, 100083 Beijing, China 3GRINM Resources and Environment Tech. Co., Ltd., 100088 Beijing, China 4General Research Institute for Nonferrous Metal, Beijing 100088, China Correspondence should be addressed to Junyan Yang; [email protected] and Lijun Wang; [email protected] Received 5 November 2019; Revised 4 January 2020; Accepted 10 January 2020; Published 11 February 2020 Guest Editor: Yaowen Xing Copyright © 2020 Junyan Yang et al. /is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. /e mechanism of the formation of the hydrophobic agglomerate in fine scheelite flotation was studied using zeta potential measurement, contact angle measurement, optical microscope measurement, and atomic force microscopy (AFM) colloid probe technology. Zeta potential measurement results confirmed the adsorption of sodium oleate on scheelite, fluorite, and calcite surface and surface potential difference at different pH values of ultrapure water. Contact angle measurement results confirmed the surface of nature scheelite, fluorite, and calcite was hydrophilic, and the surface after thread by sodium oleate solution was hydrophobic. -

Recovery of Fluorite and Byproducts from Fish Creek Deposit, Eureka County, NV

PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE FROM LIBRARY [RI[ 9028 Bureau of Mines Report of Inve.stigations/1986 Recovery of Fluorite and Byproducts From Fish Creek Deposit, Eureka County, NV By F. W. Benn, D. G. Foot, Jr., and J. L. Huiatt -/ I UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 1 1 Report of Investigations 9028 Recovery of Fluorite and Byproducts From Fish Creek Deposit, Eureka County, NV By F. W. Benn, D. G. Foot, Jr., and J. L. Huiatt UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Don~ld Paul Hodel, Secretary BUREAU OF MINES Robert C. Horton; Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data: Benn, F. W. (Freddy W.) Recovery of fluorite and byproducts from Fish Creek deposit, Eur:eka County, NV. (Report of investigations I United States Department of the Inte- rior, Bureau of Mines ; 9028) Bi bliography: p. 13. Supt. of Docs. no.: I 28.~3:9028. 1. Fluorspar-Nevada-Eureka County. 2. Flotation. I. Foot, D. G. (Donald G.h II. Huiatt, J.~. III. Title: Report of investigations (United States. Bureau of Mines) ; 9028. I- TN23.U43 [TN948.F6] 6228 [622'.395] 86.600051 CONTENTS Aba tract •••••••••••••••••••. fill ••• fill •••••••••••••••••••••• ,. ....................... 1 Introduction .•..••••.••.•••.•..•.••••••.....••........•••••.•••••••.•.••••••.•. 2 Experimental materials ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 3 Experimental procedures and results •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 Fluorite-beryllium sample •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 Fluorite flotation ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• -

FLUORITE Caf2 the Only Common Fluoride Mineral, with Widely Varying Parageneses

FLUORITE CaF2 The only common fluoride mineral, with widely varying parageneses. It occurs as an accessory mineral in granites and pegmatites, in hydrothermal veins, and in vugs in limestones. Northern and Southern Peninsulas. Bay County: Quarry just east of Bay City on M- 25: Brown, 5 mm cubes in vugs in limestone. Figure 79: Iridescent brown fluorite crystals to 4 mm with calcite from the Thompson-McCully quarry, near Newport, Monroe County. A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum specimen No. DM 22651, Jeffrey Scovil photograph. Gogebic County: In Archean biotite gneiss in sections 4 and 5, T45N, R40W, north of County Road 206 and west of U.S. 45 as a local rock accessory mineral along with apatite, allanite, magnetite, and zircon (Sims et al., 1984). Although fluorite is disseminated through the rock, it apparently is more abundant in recrystallized coarser-grained zones. Fluorite also occurs as an Figure 78: Fluorite crystals in calcite on conglomerate from accessory species in very fine-grained biotite schist near Eagle River, Keweenaw County. Largest crystal is 1.5 and cataclastic biotite gneiss. cm across. A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum specimen No. DM 15702, Jeffrey Scovil photograph. Isabella County: 16 km north of Mount Pleasant: Clear crystals 0.5 to 5 cm square from a Delta County: Stonington Rock quarry, near Detroit River Series dolomite core cut from 3,743 Stonington: As dark purple coatings on fracture to 3,753 feet in the Mellon and Pollock Number 1 surfaces in dolostone (M. J. Elder, personal Crowley [well] in section 27 T16N, R4W (n.b., communication, 2003). -

Characterization of the Rare-Earth Mineralogy at the Pea Ridge Deposit, Missouri

RI 9331 REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS/1990 PLEASE DO Nor REMOVE FRCM LIBRARY Characterization of the Rare-Earth Mineralogy at the Pea Ridge Deposit, Missouri By C. W. Whitten and R. J. Yancey 1910 * 80 * 1990 YEARS BUREAU OF MINES UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. Bureau of Min~s ->1-"Cnnr'''n'' .... " \, k"c:,\\-;~e::rc 't 1 Cen t er E. ~ l~) I .. ' : : ,," -:;-y r1'J~. ~r::J-. :;.·~, ~'_' J' i' L'~.\j · .. ·(y M ission: As the Nation's principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has respon sibility for most of our nationally-owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering wise use of our land and w ater resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, pre serving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and pro viding for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation, Th e Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to assure that their development is in the best interests of all our people. The Department also promotes the goals of the Take Pr ide in A merica campaign by encouraging stewardship and citizen responsibil ity for the public lands and promoting citizen par ticipation in their care . Th e Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reser vation communities and for people who live in Island Territories under U.S . Administration, Report of Investigations 9331 Characterization of the Rare-Earth Mineralogy at the Pea Ridge Deposit, Missouri By C. W. Whitten and R. J. Yancey UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Manuel Lujan, Jr., Secretary BUREAU OF MINES T S Ary, Director ...