Global Challenges in Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Supply, Use, and Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gavi's Vaccine Investment Strategy

Gavi’s Vaccine Investment Strategy Deepali Patel THIRD WHO CONSULTATION ON GLOBAL ACTION PLAN FOR INFLUENZA VACCINES (GAP III) Geneva, Switzerland, 15-16 November 2016 www.gavi.org Vaccine Investment Strategy (VIS) Evidence-based approach to identifying new vaccine priorities for Gavi support Strategic investment Conducted every 5 years decision-making (rather than first-come- first-serve) Transparent methodology Consultations and Predictability of Gavi independent expert advice programmes for long- term planning by Analytical review of governments, industry evidence and modelling and donors 2 VIS is aligned with Gavi’s strategic cycle and replenishment 2011-2015 Strategic 2016-2020 Strategic 2021-2025 period period 2008 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 RTS,S pilot funding decision VIS #1 VIS #2 VIS #3 MenA, YF mass campaigns, JE, HPV Cholera stockpile, Mid 2017 : vaccine ‘long list’ Rubella, Rabies/cholera studies, Oct 2017 : methodology Typhoid Malaria – deferred Jun 2018 : vaccine shortlist conjugate Dec 2018 : investment decisions 3 VIS process Develop Collect data Develop in-depth methodology and Apply decision investment decision framework for cases for framework with comparative shortlisted evaluation analysis vaccines criteria Phase I Narrow long list Phase II Recommend for Identify long list to higher priority Gavi Board of vaccines vaccines approval of selected vaccines Stakeholder consultations and independent expert review 4 Evaluation criteria (VIS #2 – 2013) Additional Health Implementation -

Package Insert

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION ----------------------------- CONTRAINDICATIONS ------------------------------------- These highlights do not include all the information needed to use ® • History of severe allergic reactions (e.g., anaphylaxis) to egg proteins, or any FLUVIRIN (Influenza Virus Vaccine) safely and effectively. See full ® ® component of FLUVIRIN , or life-threatening reactions to previous influenza prescribing information for FLUVIRIN . vaccinations. (4.1, 11) FLUVIRIN® (Influenza Virus Vaccine) Suspension for Intramuscular Injection ---------------------- WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ------------------------------ 2017-2018 Formula • If Guillain-Barré syndrome has occurred within 6 weeks of receipt of prior Initial US Approval: 1988 influenza vaccine, the decision to give FLUVIRIN® should be based on -------------------------- INDICATIONS AND USAGE ---------------------------------- careful consideration of the potential benefits and risks. (5.1) ® • FLUVIRIN is an inactivated influenza virus vaccine indicated for active • Immunocompromised persons may have a reduced immune response to immunization of persons 4 years of age and older against influenza disease FLUVIRIN®. (5.2) caused by influenza virus subtypes A and type B contained in the vaccine (1). • The tip caps of the FLUVIRIN® prefilled syringes may contain natural rubber • FLUVIRIN® is not indicated for children less than 4 years of age because latex which may cause allergic reactions in latex sensitive individuals. there is evidence of diminished immune response -

Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule

Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule UNITED STATES for ages 19 years or older 2021 Recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices How to use the adult immunization schedule (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip) and approved by the Centers for Disease Determine recommended Assess need for additional Review vaccine types, Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov), American College of Physicians 1 vaccinations by age 2 recommended vaccinations 3 frequencies, and intervals (www.acponline.org), American Academy of Family Physicians (www.aafp. (Table 1) by medical condition and and considerations for org), American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (www.acog.org), other indications (Table 2) special situations (Notes) American College of Nurse-Midwives (www.midwife.org), and American Academy of Physician Assistants (www.aapa.org). Vaccines in the Adult Immunization Schedule* Report y Vaccines Abbreviations Trade names Suspected cases of reportable vaccine-preventable diseases or outbreaks to the local or state health department Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine Hib ActHIB® y Clinically significant postvaccination reactions to the Vaccine Adverse Event Hiberix® Reporting System at www.vaers.hhs.gov or 800-822-7967 PedvaxHIB® Hepatitis A vaccine HepA Havrix® Injury claims Vaqta® All vaccines included in the adult immunization schedule except pneumococcal 23-valent polysaccharide (PPSV23) and zoster (RZV) vaccines are covered by the Hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccine HepA-HepB Twinrix® Vaccine Injury Compensation Program. Information on how to file a vaccine injury Hepatitis B vaccine HepB Engerix-B® claim is available at www.hrsa.gov/vaccinecompensation. Recombivax HB® Heplisav-B® Questions or comments Contact www.cdc.gov/cdc-info or 800-CDC-INFO (800-232-4636), in English or Human papillomavirus vaccine HPV Gardasil 9® Spanish, 8 a.m.–8 p.m. -

UNICEF Deep-Dive 2020, Vaccine Industry Consultation UNICEF’S Tentative Vaccine Tender Calendar for the Upcoming Period INFLUENZA Deep-Dive Agenda

UNICEF Deep-dive 2020, Vaccine Industry Consultation UNICEF’s Tentative Vaccine Tender Calendar for the upcoming period INFLUENZA Deep-dive Agenda • Background and challenges • Feedback from the industry • Gavi learning agenda for seasonal influenza • Tender timelines • Key takeaways 4 Background & Challenges • Immunization programmes, vaccines, and auxiliary supplies for seasonal influenza are primarily funded through a country’s own health budget. • Due to limited funding, seasonal influenza programmes are often not implemented in LICs and MICs. • Historically, UNICEF has procured limited quantities of influenza vaccine on behalf of countries. • UNICEF often receives requests for supply of seasonal influenza vaccine late and after suppliers have determined the production volume for the global market. • Due to COVID-19, the demand for seasonal influenza vaccines through UNICEF has increased during 2020, and realized late which let to constrained availability for countries procuring through UNICEF. UNICEF plans to tender earlier to counter this risk. Feedback from the industry What should UNICEF do differently to incentivize your participation in the future tenders for seasonal influenza vaccines? Feedback from the industry Measures taken by UNICEF • Tender one year in advance to block the • Advance tender timelines doses for UNICEF. • Stakeholders reminded of: • Multi-year tender and LTA o the short window for production planning and supply • UNICEF take risks and commit to pay for o importance of timely and accurate the doses even they are not materialised forecasting into orders. • Published a Supply Note on Seasonal Influenza Vaccines in English & French. • Working with countries to improve longer- term forecast accuracy. 6 Gavi learning agenda for seasonal influenza • Background: only 8% of Gavi eligible • Duration of the project: 2021 – 2022 countries have seasonal influenza immunization programmes, and most • Targeted countries: Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya & countries in the African region do not have Uganda national influenza immunization policies. -

Using Influenza Vaccination Location Data from the 2018 Behavioral Risk

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Using Influenza Vaccination Location Data from the 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) to Expand COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Victoria Fonzi 1, Kiran Thapa 2, Kishor Luitel 3, Heather Padilla 4, Curt Harris 5, M. Mahmud Khan 1, Glen Nowak 6 and Janani Rajbhandari-Thapa 1,* 1 Department of Health Policy and Management, College of Public Health, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA; [email protected] (V.F.); [email protected] (M.M.K.) 2 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, College of Public Health, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA; [email protected] 3 School of Agriculture, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN 37132, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Health Promotion & Behavior, College of Public Health, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA; [email protected] 5 Institute for Disaster Management, College of Public Health, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA; [email protected] 6 Grady College Center for Health and Risk Communication, Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Citation: Fonzi, V.; Thapa, K.; Luitel, K.; Padilla, H.; Harris, C.; Khan, M.M.; Abstract: Effective COVID-19 vaccine distribution requires prioritizing locations that are accessible Nowak, G.; Rajbhandari-Thapa, J. to high-risk target populations. However, little is known about the vaccination location preferences Using Influenza Vaccination Location Data from the 2018 Behavioral Risk of individuals with underlying chronic conditions. Using data from the 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) to Surveillance System (BRFSS), we grouped 162,744 respondents into high-risk and low-risk groups Expand COVID-19 Vaccination for COVID-19 and analyzed the odds of previous influenza vaccination at doctor’s offices, health Coverage. -

Vaccine Names and Abbreviations Vaccine Names and Abbreviations Many Vaccines Are Documented in an Abbreviation and Not by Their Full Name

Vaccine Names and Abbreviations Vaccine Names and Abbreviations Many vaccines are documented in an abbreviation and not by their full name. This page is designed to assist you in interpreting both old and new immunization records such as the yellow California Immunization Record, the International Certificate of Vaccination (Military issued shot record) or the Mexican Immunization Card described in the shaded sections. Vaccine Abbreviation/Name What it Means Polio Oral Polio oral poliovirus vaccine (no longer used in U.S.) OPV Orimune Trivalent Polio TOPV Sabin oral poliovirus Inactivated Polio injectable poliovirus vaccine eIPV IPOL IPV Pentacel combination vaccine: DTaP/Hib/IPV Pediarix combination vaccine: diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis, Haemophilus influenzae type b and inactivated poliovirus (DTaP/IPV/Hep B) DTP or DPT combination vaccine: diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (no longer DTP Tri-Immunol available in U.S.) (Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis) Triple combination vaccine: difteria, tétano, tos ferina (diphtheria, tetanus pertussis) DT combination vaccine: diphtheria and tetanus vaccine (infant vaccine without pertussis component used through age 6) DTaP combination vaccine: diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis DTaP/Tdap Acel-Imune Certiva (Diphtheria, Tetanus, acellular Daptacel Pertussis) Infanrix Tripedia Tdap combination vaccine: tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis Adacel (improved booster vaccine containing pertussis for adolescents Boostrix and adults) DTP-Hib combination vaccine: diphtheria, tetanus, -

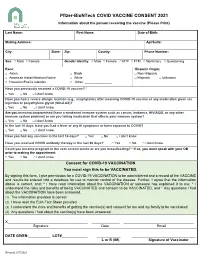

Pfizer-Biontech COVID VACCINE CONSENT 2021 Information About the Person Receiving the Vaccine (Please Print)

Pfizer-BioNTech COVID VACCINE CONSENT 2021 Information about the person receiving the vaccine (Please Print) Last Name: First Name: Date of Birth: Mailing Address: Apt/Suite: City: State: Zip: County: Phone Number: Sex: □ Male □ Female Gender Identity: □ Male □ Female □ MTF □ FTM □ Nonbinary □ Questioning Race: Hispanic Origin: □ Asian □ Black □ Non-Hispanic □ American Indian/Alaskan Native □ White □ Hispanic □ Unknown □ Hawaiian/Pacific Islander □ Other: _______________ Have you previously received a COVID-19 vaccine? * □ Yes □ No □ I don’t know Have you had a severe allergic reaction (e.g., anaphylaxis) after receiving COVID-19 vaccine or any medication given via injection or polyethylene glycol (MiraLAX)? □ Yes □ No □ I don’t know Are you immunocompromised (have a weakened immune system such as cancer, leukemia, HIV/AIDS, or any other immune system problem) or are you taking medication that affects your immune system? □ Yes □ No □ I don’t know In the last 10 days, have you had a fever or any ill symptoms or been exposed to COVID? □ Yes □ No □ I don’t know Have you had any vaccines in the last 14 days? □ Yes □ No □ I don’t know Have you received COVID antibody therapy in the last 90 days? □ Yes □ No □ I don’t know Could you become pregnant in the next several weeks or are you breastfeeding? * If so, you must speak with your OB prior to making the appointment. □ Yes □ No □ I don’t know Consent for COVID-19 VACCINATION You must sign this to be VACCINATED. By signing this form, I give permission for a COVID-19 VACCINATION to be administered and a record of the VACCINE and results be entered into a database for use to monitor control of the disease. -

Product Information for Pandemrix H1N1 Pandemic Influenza Vaccine

Attachment 1: Product information for Pandemrix H1N1 pandemic influenza vaccine. Influenza virus haemagglutinin (A/California/7/2009(H1N1)v-like strain). GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd. PM-2010- 02995-3-2 Final 12 February 2013. This Product Information was approved at the time this AusPAR was published. PANDEMRIX™ H1N1 PRODUCT INFORMATION Pandemic influenza vaccine (split virion, inactivated, AS03 adjuvanted) NAME OF THE MEDICINE PANDEMRIX H1N1, emulsion and suspension for emulsion for injection. Pandemic influenza vaccine (split virion, inactivated, AS03 adjuvanted). DESCRIPTION Each 0.5mL vaccine dose contains 3.75 micrograms1 of antigen2 of A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)v- like strain and is adjuvanted with AS033. 1haemagglutinin 2propagated in eggs 3The GlaxoSmithKline proprietary AS03 adjuvant system is composed of squalene (10.68 milligrams), DL-α-tocopherol (11.86 milligrams) and polysorbate 80 (4.85 milligrams) This vaccine complies with the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendation for the pandemic. Each 0.5mL vaccine dose also contains the excipients Polysorbate 80, Octoxinol 10, Thiomersal, Sodium Chloride, Disodium hydrogen phosphate, Potassium dihydrogen phosphate, Potassium Chloride and Magnesium chloride. The vaccine may also contain the following residues: egg residues including ovalbumin, gentamicin sulfate, formaldehyde, sucrose and sodium deoxycholate. CLINICAL TRIALS This section describes the clinical experience with PANDEMRIX H1N1 after a single dose in healthy adults aged 18 years and older and the mock-up vaccines (Pandemrix H5N1) following a two-dose administration. Mock-up vaccines contain influenza antigens that are different from those in the currently circulating influenza viruses. These antigens can be considered as “novel” antigens and simulate a situation where the target population for vaccination is immunologically naïve. -

Safety and Immunogenicity of a Plant-Produced

Viruses 2012, 4, 3227-3244; doi:10.3390/v4113227 OPEN ACCESS viruses ISSN 1999-4915 www.mdpi.com/journal/viruses Article Safety and Immunogenicity of a Plant-Produced Recombinant Hemagglutinin-Based Influenza Vaccine (HAI-05) Derived from A/Indonesia/05/2005 (H5N1) Influenza Virus: A Phase 1 Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Escalation Study in Healthy Adults Jessica A. Chichester, R. Mark Jones, Brian J. Green, Mark Stow, Fudu Miao, George Moonsammy, Stephen J. Streatfield and Vidadi Yusibov * Fraunhofer USA, Center for Molecular Biotechnology, Newark, DE 19711, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (J.A.C.); [email protected] (R.M.J.); [email protected] (B.J.G.); [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (F.M.); [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (S.J.S.); [email protected] (V.Y.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-302-369-3766; Fax: +1-302-369-8955. Received: 25 October 2012; in revised form: 15 November 2012 / Accepted: 16 November 2012 / Published: 19 November 2012 Abstract: Recently, we have reported [1,2] on a subunit influenza vaccine candidate based on the recombinant hemagglutinin protein from the A/Indonesia/05/2005 (H5N1) strain of influenza virus, produced it using ‘launch vector’-based transient expression technology in Nicotiana benthamiana, and demonstrated its immunogenicity in pre-clinical studies. Here, we present the results of a first-in-human, Phase 1 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study designed to investigate safety, reactogenicity and immunogenicity of three escalating dose levels of this vaccine, HAI-05, (15, 45 and 90 µg) adjuvanted with Alhydrogel® (0.75 mg aluminum per dose) and the 90 µg dose level without Alhydrogel®. -

HPV and Adolescent Vaccine Toolkit: Clinician Guide Contents

HPV and Adolescent Vaccine Toolkit: Clinician Guide CONTENTS I. 2018 IMMUNIZATION SCHEDULES & SCREENING RESOURCES Recommended & Catch-up Immunization Schedule (Birth-18 Years) Lists the ages or age range each vaccine is recommended. Schedules are updated annually. Please visit https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/ for the most up-to-date schedules. Clinician FAQ: CDC Recommendations for HPV Vaccine 2-Dose Schedules Helps explain the new HPV vaccine recommendation for adolescents (2 doses recommended for adolescents starting the series before their 15th birthday; 3 doses recommended for adolescents starting the series after their 15th birthday) and provides tips for talking to parents about the change. HPV 2-Dose Decision Tree Follow the decision tree chart to determine whether your patient needs two or three doses of HPV vaccine. II. ADDRESSING VACCINE HESITANCY Talking to Parents About the HPV Vaccine A collection of questions parents may have surrounding the HPV vaccine and responses healthcare providers can use to address the concerns. Let’s Talk Vaccines: A Guide to Conversations About Immunizations Parents ask tough questions! Use this resource from Northwest Vax to provide a strong recommendation using the Ask. Acknowledge. Advise model. III. BEST PRACTICES AND STRATEGIES FOR IMPROVING IMMUNIZATION COVERAGE RATES Strategies for Improving Adolescent Immunization Coverage Rates Use the strategies in this AAP resource to help your practice improve adolescent immunization coverage rates among your patients. Documenting Parental Refusal to Have Their Children Vaccinated Provides tips from the AAP on ways to communicate with and educate parents who refuse immunizations. Includes a template for use by health care providers to document refusals. -

Recommended Composition of Influenza Virus Vaccines for Use in the 2021- 2022 Northern Hemisphere Influenza Season

Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2021- 2022 northern hemisphere influenza season February 2021 WHO convenes technical consultations1 in February and September each year to recommend viruses for inclusion in influenza vaccines 2 for the northern and southern hemisphere influenza seasons, respectively. This recommendation relates to the influenza vaccines for use in the northern hemisphere 2021-2022 influenza season. A recommendation will be made in September 2021 relating to vaccines that will be used for the southern hemisphere 2022 influenza season. For countries in tropical and subtropical regions, WHO recommendations for influenza vaccine composition (northern hemisphere or southern hemisphere) are available on the WHO Global Influenza Programme website3. Seasonal influenza activity Public health and laboratory responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the coronavirus SARS- CoV-2, initially led to reduced influenza surveillance and/or reporting activities in many countries, which have been improving. Additionally, COVID-19 mitigation strategies including restrictions on travel, use of respiratory protection, and social-distancing measures in most countries have contributed to decreased influenza activity. Overall, record-low levels of influenza detections were reported and fewer viruses were available for characterization during the September 2020 to January 2021 time- period than in previous years. Between September 2020 and January 2021, influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H3N2) and influenza B viruses circulated in very low numbers and the relative proportions of the viruses circulating varied among reporting countries. Globally, since September 2020, influenza activity was mostly reported from countries in the tropics and subtropics and some countries in the temperate zone of the northern hemisphere. -

First Do No Harm: Mandatory Influenza Vaccination Policies for Healthcare Personnel Help Protect Patients

First Do No Harm: Mandatory InfluenzaV accination Policies for Healthcare Personnel Help Protect Patients First Do No Harm: Mandatory Influenza Vaccination Policies for Healthcare Personnel Help Protect Patients view the complete list: Refertothepositionstatementsoftheleadingmedicalorganizationslistedbelowtohelp www.immunize.org/honor-roll/ youdevelopandimplementamandatoryinfluenzavaccinationpolicyatyourhealthcare influenza-mandates institutionormedicalsetting.Policytitles,publicationdates,links,andexcerptsfollow. American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) American Public Health Association (APHA) AAFP Mandatory Influenza Vaccination of Health Care Personnel (6/11) Annual Influenza Vaccination Requirements for Health Workers (11/9/10) ▶ www.aafp.org/news-now/health-of-the-public/20110613 ▶ www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/ mandatoryfluvacc.html policy-database/2014/07/11/14/36/annual-influenza-vaccination- “TheAAFPsupportsannualmandatoryinfluenzaimmunizationforhealthcare requirements-for-health-workers personnel(HCP)exceptforreligiousormedicalreasons(notpersonalprefer- “Encouragesinstitutional,employer,andpublichealthpolicytorequireinfluenza ences).IfHCParenotvaccinated,policiestoadjustpracticeactivitiesduringflu vaccinationofallhealthworkersasapreconditionofemploymentandthere- seasonareappropriate(e.g.wearmasks,refrainfromdirectpatientcare).” afteronanannualbasis,unlessamedicalcontraindicationrecognizedinnational guidelinesisdocumentedintheworker’shealthrecord.” American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)