A Spider and Other Arachnids from the Devonian of New York, and Reinterpretations of Devonian Araneae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 AAS Abstracts

2017 AAS Abstracts The American Arachnological Society 41st Annual Meeting July 24-28, 2017 Quéretaro, Juriquilla Fernando Álvarez Padilla Meeting Abstracts ( * denotes participation in student competition) Abstracts of keynote speakers are listed first in order of presentation, followed by other abstracts in alphabetical order by first author. Underlined indicates presenting author, *indicates presentation in student competition. Only students with an * are in the competition. MAPPING THE VARIATION IN SPIDER BODY COLOURATION FROM AN INSECT PERSPECTIVE Ajuria-Ibarra, H. 1 Tapia-McClung, H. 2 & D. Rao 1 1. INBIOTECA, Universidad Veracruzana, Xalapa, Veracruz, México. 2. Laboratorio Nacional de Informática Avanzada, A.C., Xalapa, Veracruz, México. Colour variation is frequently observed in orb web spiders. Such variation can impact fitness by affecting the way spiders are perceived by relevant observers such as prey (i.e. by resembling flower signals as visual lures) and predators (i.e. by disrupting search image formation). Verrucosa arenata is an orb-weaving spider that presents colour variation in a conspicuous triangular pattern on the dorsal part of the abdomen. This pattern has predominantly white or yellow colouration, but also reflects light in the UV part of the spectrum. We quantified colour variation in V. arenata from images obtained using a full spectrum digital camera. We obtained cone catch quanta and calculated chromatic and achromatic contrasts for the visual systems of Drosophila melanogaster and Apis mellifera. Cluster analyses of the colours of the triangular patch resulted in the formation of six and three statistically different groups in the colour space of D. melanogaster and A. mellifera, respectively. Thus, no continuous colour variation was found. -

Spider-Silk-Talk.Pdf

Spiders and their webs • 319Ma-present • 109 families • 40,000 species Orb web - family Araneidae Cobweb – family Theridiidae Sheet web - Family Linyphiidae Funnel web - Sydney funnel-web spider (Atrax robustus) Effect of Caffeine on the weaving behavior Spider’s silk plant Spider feet – front spinneret Natural spinning process Silk glands Gland Silk Use Dragline silk—used for the web’s outer rim and spokes and the Ampullate (Major) lifeline. Ampullate (Minor) Used for temporary scaffolding during web construction. Flagelliform Capture-spiral silk—used for the capturing lines of the web. Tubuliform Egg cocoon silk—used for protective egg sacs. Used to wrap and secure freshly captured prey; used in the male Aciniform sperm webs; used in stabilimenta Aggregate A silk glue of sticky globules Piriform Used to form bonds between separate threads for attachment points Silk types Silk Use Used for the web's outer rim and spokes and the major-ampullate (dragline) silk lifeline. Can be as strong per unit weight as steel, but much tougher. Used for the capturing lines of the web. Sticky, capture-spiral silk extremely stretchy and tough. tubiliform (aka cylindriform) silk Used for protective egg sacs. Stiffest silk. Used to wrap and secure freshly captured prey. aciniform silk Two to three times as tough as the other silks, including dragline. Used for temporary scaffolding during web minor-ampullate silk construction Different silk types produced by Araneae female spider Are insects specialized uni-taskers? A spider’s task is simple. To weave its web, catch a prey and eat it. But how? So many specialized tools. -

North American Spiders of the Genera Cybaeus and Cybaeina

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Utah: J. Willard Marriott Digital... BULLETIN OF THE UNIVERSITY OF UTAH Volume 23 December, 1932 No. 2 North American Spiders of the Genera Cybaeus and Cybaeina BY RALPH V. CHAMBERLIN and WILTON IVIE BIOLOGICAL SERIES, Vol. II, No. / - PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF UTAH SALT LAKE CITY THE UNIVERSITY PRESS UNIVERSITY OF UTAH SALT LAKE CITY A Review of the North American Spider of the Genera Cybaeus and Cybaeina By R a l p h V. C h a m b e r l i n a n d W i l t o n I v i e The frequency with which members of the Agelenid genus Cybaeus appeared in collections made by the authors in the mountainous and timbered sections of the Pacific coast region and the representations therein of various apparently undescribed species led to the preparation of this review of the known North American forms. One species hereto fore placed in Cybaeus is made the type of a new genus Cybaeina. Most of our species occur in the western states; and it is probable that fur ther collecting in this region will bring to light a considerable number of additional forms. The drawings accompanying the paper were made from specimens direct excepting in a few cases where material was not available. In these cases the drawings were copied from the figures published by the authors of the species concerned, as indicated hereafter in each such case, but these drawings were somewhat revised to conform with the general scheme of the other figures in order to facilitate comparison. -

Newsletter of the Biological Survey of Canada (Terrestrial Arthropods)

Spring 1999 Vol. 18, No. 1 NEWSLETTER OF THE BIOLOGICAL SURVEY OF CANADA (TERRESTRIAL ARTHROPODS) Table of Contents General Information and Editorial Notes ............(inside front cover) News and Notes Activities at the Entomological Societies’ Meeting ...............1 Summary of the Scientific Committee Meeting.................2 EMAN National Meeting ...........................12 MacMillan Coastal Biodiversity Workshop ..................13 Workshop on Biodiversity Monitoring.....................14 Project Update: Family Keys ..........................15 Canadian Spider Diversity and Systematics ..................16 The Quiz Page..................................28 Selected Future Conferences ..........................29 Answers to Faunal Quiz.............................31 Quips and Quotes ................................32 List of Requests for Material or Information ..................33 Cooperation Offered ..............................39 List of Email Addresses.............................39 List of Addresses ................................41 Index to Taxa ..................................43 General Information The Newsletter of the Biological Survey of Canada (Terrestrial Arthropods) appears twice yearly. All material without other accreditation is prepared by the Secretariat for the Biological Survey. Editor: H.V. Danks Head, Biological Survey of Canada (Terrestrial Arthropods) Canadian Museum of Nature P.O. Box 3443, Station “D” Ottawa, Ontario K1P 6P4 TEL: 613-566-4787 FAX: 613-364-4021 E-mail: [email protected] Queries, -

The Phylogeny of Fossil Whip Spiders Russell J

Garwood et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2017) 17:105 DOI 10.1186/s12862-017-0931-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The phylogeny of fossil whip spiders Russell J. Garwood1,2*, Jason A. Dunlop3, Brian J. Knecht4 and Thomas A. Hegna4 Abstract Background: Arachnids are a highly successful group of land-dwelling arthropods. They are major contributors to modern terrestrial ecosystems, and have a deep evolutionary history. Whip spiders (Arachnida, Amblypygi), are one of the smaller arachnid orders with ca. 190 living species. Here we restudy one of the oldest fossil representatives of the group, Graeophonus anglicus Pocock, 1911 from the Late Carboniferous (Duckmantian, ca. 315 Ma) British Middle Coal Measures of the West Midlands, UK. Using X-ray microtomography, our principal aim was to resolve details of the limbs and mouthparts which would allow us to test whether this fossil belongs in the extant, relict family Paracharontidae; represented today by a single, blind species Paracharon caecus Hansen, 1921. Results: Tomography reveals several novel and significant character states for G. anglicus; most notably in the chelicerae, pedipalps and walking legs. These allowed it to be scored into a phylogenetic analysis together with the recently described Paracharonopsis cambayensis Engel & Grimaldi, 2014 from the Eocene (ca. 52 Ma) Cambay amber, and Kronocharon prendinii Engel & Grimaldi, 2014 from Cretaceous (ca. 99 Ma) Burmese amber. We recovered relationships of the form ((Graeophonus (Paracharonopsis + Paracharon)) + (Charinus (Stygophrynus (Kronocharon (Charon (Musicodamon + Paraphrynus)))))). This tree largely reflects Peter Weygoldt’s 1996 classification with its basic split into Paleoamblypygi and Euamblypygi lineages; we were able to score several of his characters for the first time in fossils. -

Cribellum and Calamistrum Ontogeny in the Spider Family Uloboridae: Linking Functionally Related but Sbparate Silk Spinning Features

2OOl. The Journal of Arachnology 29:22O-226 CRIBELLUM AND CALAMISTRUM ONTOGENY IN THE SPIDER FAMILY ULOBORIDAE: LINKING FUNCTIONALLY RELATED BUT SBPARATE SILK SPINNING FEATURES Brent D. Opelt: Department of BioLogy, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, Virginia 24061 USA ABSTRACT. The fourth metatarsusof cribellatespiders bears a setal comb, the calamistrum,that sweeps over the cribellum, drawing fibrils from its spigots and helping to combine these with the capture thread's supporting fibers. In four uloborid species (Hyptiotes cavatus, Miagrammopes animotus, Octonoba sinensis, Uloborus glomosus), calamistrum length and cribellum width have similar developmental trajec- tories, despite being borne on different regions of the body. In contrast, developmental rates of metatarsus IV and its calamistrum differ within species and vary independently among species. Thus, the growth rates of metatarsus IV and the calamistrum are not coupled, freeing calamistrum length to track cribellum width and metatarsus IV length to respond to changes in such features as combing behavior and abdomen dimensions. Keywords: Cribellar thread, Hyptiotes cavatus, Miagrammopes animotus, Octonoba sinensis, Ulobortts glomosus Members of the family Uloboridae produce ond instars (Opell 1979). However, their cri- cribellar prey capture threads formed of a bella and calamistra are not functional until sheath of fine, looped fibrils that surround par- they molt again to become third instars. Sec- acribellar and axial supporting fibers (Eber- ond instar orb-weaving uloborid species pro- hard & Pereira 1993: Opell 1990, 1994, 1995, duce a juvenile web that lacks a sticky spiral 1996, 1999: Peters 1983, 1984, 1986). Cri- and has many closely spaced radii (Lubin bellar fibrils come from the spigots of an oval 1986). -

By Heterophrynus Sp. (Arachnida, Phrynidae) in a Cave in the Chapada Das Mesas National Park, State of Maranhão, Brazil

Crossref 10 ANOS Similarity Check Powered by iThenticate SCIENTIFIC NOTE DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18561/2179-5746/biotaamazonia.v10n1p49-52 Predation of Tropidurus oreadicus (Reptilia, Tropiduridae) by Heterophrynus sp. (Arachnida, Phrynidae) in a cave in the Chapada das Mesas National Park, state of Maranhão, Brazil Fábio Antônio de Oliveira1, Gabriel de Avila Batista2, Karla Dayane de Lima Pereira3, Lucas Gabriel Machado Frota4, Victoria Sousa5, Layla Simone dos Santos Cruz6, Karll Cavalcante Pinto7 1. Biólogo (Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Goiás, Brasil). Doutorando em Geologia (Universidade de Brasília, Brasil). [email protected] http://lattes.cnpq.br/6651314736341253 http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8125-6339 2. Biólogo (Anhanguera Educacional, Brasil). Doutorando em Recursos Naturais do Cerrado (Universidade Estadual de Goiás, Brasil). [email protected] http://lattes.cnpq.br/1131941234593219 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4284-2591 3. Bióloga (Anhanguera Educacional, Brasil). Mestranda em Conservação de Recursos Naturais do Cerrado (Instituto Federal Goiano, Brasil). [email protected] http://lattes.cnpq.br/4328373742442270 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1578-8948 4. Biólogo (Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Goiás, Brasil). Analista Ambiental da Biota Projetos e Consultoria Ambiental LTDA, Brasil. [email protected] http://lattes.cnpq.br/7083829373324504 http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6907-9480 5. Bióloga (Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Goiás, Brasil). Mestranda em Ecologia e Evolução (Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brasil). [email protected] http://lattes.cnpq.br/0747140109675656 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2818-5698 6. Bióloga (Centro Universitário de Goiás, Brasil). Especialista em Perícia, Auditoria e Gestão Ambiental (Instituto de Especialização e Pós-Graduação (IEPG)/Faculdade Oswaldo Cruz, Brasil). -

Comparative Analysis of Courtship in <I>Agelenopsis</I> Funnel-Web Spiders

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2012 Comparative analysis of courtship in Agelenopsis funnel-web spiders (Araneae, Agelenidae) with an emphasis on potential isolating mechanisms Audra Blair Galasso [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons Recommended Citation Galasso, Audra Blair, "Comparative analysis of courtship in Agelenopsis funnel-web spiders (Araneae, Agelenidae) with an emphasis on potential isolating mechanisms. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1377 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Audra Blair Galasso entitled "Comparative analysis of courtship in Agelenopsis funnel-web spiders (Araneae, Agelenidae) with an emphasis on potential isolating mechanisms." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. Susan E. Riechert, Major -

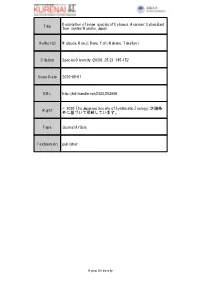

Title Description of a New Species of Cybaeus (Araneae: Cybaeidae

Description of a new species of Cybaeus (Araneae: Cybaeidae) Title from central Honshu, Japan Author(s) Matsuda, Kenji; Ihara, Yoh; Nakano, Takafumi Citation Species Diversity (2020), 25(2): 145-152 Issue Date 2020-08-07 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/253698 © 2020 The Japanese Society of Systematic Zoology; 許諾条 Right 件に基づいて掲載しています。 Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Species Diversity 25: 145–152 Published online 7 August 2020 DOI: 10.12782/specdiv.25.145 Description of a New Species of Cybaeus (Araneae: Cybaeidae) from Central Honshu, Japan Kenji Matsuda1, Yoh Ihara2, and Takafumi Nakano1,3 1 Department of Zoology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan E-mail: [email protected] 2 Hiroshima Environment & Health Association, 9-1 Hirose-kita-machi, Naka-ku, Hiroshima 730-8631, Japan 3 Corresponding author (Received 9 March 2020; Accepted 27 April 2020) http://zoobank.org/8715C237-1C34-46E8-8877-8B877F083FA7 A new spider species, Cybaeus daimonji, from Kyoto, western-central Honshu, Japan is described based on both sexes. The shape of epigyne indicates that this new species is close to C. communis Yaginuma, 1972, C. kirigaminensis Komatsu, 1963, C. maculosus Yaginuma, 1972 and C. shinkaii (Komatsu, 1970), which are distributed in eastern to central Honshu. Nuclear internal transcribed spacer 1, 28S ribosomal RNA and histone H3 as well as mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I, 12S ribosomal RNA and 16S ribosomal RNA sequences of the new species are provided for future phylogenetic studies. Key Words: Arachnida, RTA clade, epigeic, retreat, Mt. Daimonjiyama, molecular identification. -

A New Species of Pionothele from Gobabeb, Namibia (Araneae, Mygalomorphae, Nemesiidae)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeysA new 851: 17–25species (2019) of Pionothele from Gobabeb, Namibia (Araneae, Mygalomorphae, Nemesiidae) 17 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.851.31802 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research A new species of Pionothele from Gobabeb, Namibia (Araneae, Mygalomorphae, Nemesiidae) Jason E. Bond1, Trip Lamb2 1 Department of Entomology & Nematology, University of California Davis, Davis, California, USA 2 Department of Biology, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA Corresponding author: Jason E. Bond ([email protected]) Academic editor: Chris Hamilton | Received 20 November 2018 | Accepted 2 February 2019 | Published 3 June 2019 http://zoobank.org/894CD479-72A2-412D-B983-7CE7C2A54E88 Citation: Bond JE, Lamb T (2019) A new species of Pionothele from Gobabeb, Namibia (Araneae, Mygalomorphae, Nemesiidae). ZooKeys 851: 17–25. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.851.31802 Abstract The mygalomorph spider genusPionothele Purcell, 1902 comprises two nominal species known only from South Africa. We describe here a new species, Pionothele gobabeb sp. n., from Namibia. This new species is currently only known from a very restricted area in the Namib Desert of western Namibia. Keywords Biodiversity, New species, Spider taxonomy, Pionothele, Nemesiidae, Mygalomorphae Introduction The nemesiid genus Pionothele Purcell, 1902 is a poorly known taxon comprising only two species described from southwestern South Africa. In Zonstein’s (2016) review of the genus, he redescribed and illustrated P. straminea Purcell, 1902 and described a second, new species P. capensis Zonstein, 2016. Similarities between female specimens of Pionothele and those in the genus Spiroctenus Simon 1889a suggest that some spe- cies described as the latter may be misidentified as the former (Zonstein 2016); con- sequently, Pionothele may be more widespread and diverse than is currently known. -

ABS-2018-Program.Pdf

CONFERENCE PROGRAM 55th Annual Conference of the Animal Behavior Society University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee August 2-6, 2018 2 ESCAPE THE CITY Discover the Natural World August 3-6, 2018 Show this ad or your conference badge to receive $5 OFF ADMISSION. MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM 800 West Wells Street, Milwaukee, WI 53233 ABS 2018 | AUGUST 2-6 414-278-2702 | www.mpm.edu 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION 2 WELCOME LETTER 3 AWARDS 4 PLENARIES & FELLOW TALKS 5 SYMPOSIA 6 WORKSHOPS 8 EVENTS & MEETINGS 9 FILM FESTIVAL 10 ABS 2019 - SAVE THE DATE 11 PROGRAM SUMMARY 12 THURSDAY, AUGUST 2 14 FRIDAY, AUGUST 3 14 SATURDAY, AUGUST 4 18 SUNDAY, AUGUST 5 21 MONDAY, AUGUST 6 24 POSTER SESSIONS 26 TALK INDEX 32 SPONSORS & EXHIBITORS 36 CAMPUS MAP OUTSIDE BACK COVER ABS 2018 | AUGUST 2-6 UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN - MILWAUKEE 2 GENERAL INFORMATION DATES CAMPUS HOUSING CHECK-IN The 55th Annual Animal Behavior Society Conference begins Delegates who are staying on campus will proceed to the Sandburg Thursday, August 2nd and concludes Monday, August 6th, 2018. Hall (3400 N. Maryland Avenue, Milwaukee, WI 53201) or River View Residence Hall (2340 North Commerce Street, Milwaukee, REGISTRATION INFORMATION WI 53211 ) to check in. The Front Desk will be available 24 hrs The Registration Desk is located in the Student Union “Pangaea at both Residence Halls for check-in. Please note that there is a Mall” on Level 1, and will be open during the following hours: $25.00 lost key fee. Wednesday 6:00 pm - 8:00 pm PRE-ORDERED MEAL PLAN CARDS & PARKING Thursday- Sunday 7:30 am - 7:30 pm PASSES Monday 7:30 am - 2:00 pm Please note that your pre-purchased meal plan card and pre- purchased parking passes will be available for pick-up at University INSTRUCTIONS TO TALK PRESENTERS Housing check-in. -

The Spider Anatomy Ontology (SPD)—A Versatile Tool to Link Anatomy with Cross-Disciplinary Data

diversity Article The Spider Anatomy Ontology (SPD)—A Versatile Tool to Link Anatomy with Cross-Disciplinary Data Martín J. Ramírez 1,* and Peter Michalik 2,* 1 Division of Arachnology, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales—CONICET, Buenos Aires C1405DJR, Argentina 2 Zoologisches Institut und Museum, Universität Greifswald, 17489 Greifswald, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.J.R.); [email protected] (P.M.) Received: 27 September 2019; Accepted: 18 October 2019; Published: 22 October 2019 Abstract: Spiders are a diverse group with a high eco-morphological diversity, which complicates anatomical descriptions especially with regard to its terminology. New terms are constantly proposed, and definitions and limits of anatomical concepts are regularly updated. Therefore, it is often challenging to find the correct terms, even for trained scientists, especially when the terminology has obstacles such as synonyms, disputed definitions, ambiguities, or homonyms. Here, we present the Spider Anatomy Ontology (SPD), which we developed combining the functionality of a glossary (a controlled defined vocabulary) with a network of formalized relations between terms that can be used to compute inferences. The SPD follows the guidelines of the Open Biomedical Ontologies and is available through the NCBO BioPortal (ver. 1.1). It constitutes of 757 valid terms and definitions, is rooted with the Common Anatomy Reference Ontology (CARO), and has cross references to other ontologies, especially of arthropods. The SPD offers a wealth of anatomical knowledge that can be used as a resource for any scientific study as, for example, to link images to phylogenetic datasets, compute structural complexity over phylogenies, and produce ancestral ontologies.