Squadron Leader Caesar Hull

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2012 Rhodesian Services Association Incorporated

September 2012 A monthly publication for the Rhodesian Services Association Incorporated Registered under the 2005 Charities Act in New Zealand number CC25203 Registered as an Incorporated Society in New Zealand number 2055431 PO Box 13003, Tauranga 3141, New Zealand. Web: www.rhodesianservices.org Secretary’s e-mail [email protected] Editor’s e-mail [email protected] Phone +64 7 576 9500 Fax +64 7 576 9501 To view all previous publications go to our Archives Greetings, The October RV and AGM are next month over the weekend 19th–21st October. Please see details further on in this newsletter. It is essential for the smooth running of the event that you book and pay for your tickets before the 12th October. Everyone is welcome – come along and have a good time. Anyone connected to Umtali and the 4th Battalion Rhodesia Regiment should make a special effort to attend this year’s RV as we have a special event planned. Unfortunately we cannot publically disclose the details yet, but anyone is welcome to contact me to get a briefing. In view of the upcoming AGM we encourage new blood to come on board the Committee for the purpose of learning the ropes and taking on positions of responsibility. In particular, the Editor and Webmaster positions are open for change. Job descriptions can be supplied on request. It is vital to the continuation of the work done by this Association that the younger generation build on the solid foundations that have been made by this Association. This newsletter is another mammoth effort, so strap in and enjoy the next thirty odd pages. -

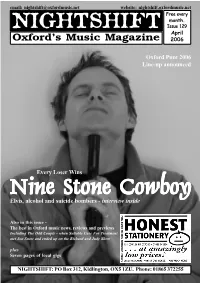

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 129 April Oxford’s Music Magazine 2006 Oxford Punt 2006 Line-up announced Every Loser Wins NineNineNine StoneStoneStone CoCoCowbowbowboyyy Elvis, alcohol and suicide bombers - interview inside Also in this issue - The best in Oxford music news, reviews and previews Including The Odd Couple - when Suitable Case For Treatment met Jon Snow and ended up on the Richard and Judy Show plus Seven pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Harlette Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] PUNT LINE-UP ANNOUNCED The line-up for this year’s Oxford featured a sold-out show from Fell Punt has been finalised. The Punt, City Girl. now in its ninth year, is a one-night This years line up is: showcase of the best new unsigned BORDERS: Ally Craig and bands in Oxfordshire and takes Rebecca Mosley place on Wednesday 10th May. JONGLEURS: Witches, Xmas The event features nineteen acts Lights and The Keyboard Choir. across six venues in Oxford city THE PURPLE TURTLE: Mark and post-rock is featured across showcase of new musical talent in centre, starting at 6.15pm at Crozer, Dusty Sound System and what is one of the strongest Punt the county. In the meantime there Borders bookshop in Magdalen Where I’m Calling From. line-ups ever, showing the quality are a limited number of all-venue Street before heading off to THE CITY TAVERN: Shirley, of new music coming out of Oxford Punt Passes available, priced at £7, Jongleurs, The Purple Turtle, The Sow and The Joff Winks Band. -

The Last Flight out of Uli

One of Jack Malloch’s unmarked DC-7’s that maintained the nightly airlift of arms and ammunition into the shrinking state of Biafra throughout 1969. This is likely the actual aircraft that made the very last flight out of Uli. Picture from Jack Malloch’s private collection. © Greg Malloch. THE LAST FLIGHT OUT OF ULI By the beginning of January 1970 in the break-away state of Biafra, Uli or ‘Airstrip Annabel’ as it was officially known, had become the country’s last remaining beacon of desperate hope in the eye of a swirling hurricane of inevitable death and destruction. Since the beginning of 1969 the little widened section of palm-tree lined roadway had become the very epitome of hell itself. The country was completely surrounded by the encroaching Nigerian forces and Uli was the only place where food and ammunition could be flown in and the starving orphans could be flown out. © Alan Brough Page !1 In early December ’69 the veteran war correspondent Al J. Venter flew into Uli. Describing his experience he said, “None of us will ever forget the heat and the noise that cloaked us like a sauna. Time meant nothing. You were simply too awed, too overwhelmed by what was going on, and the musty, unwashed immediacy of it all. Our senses were constantly sharpened by the stutter of automatic fire along the runway. The priests in their white cassocks, the rattle of war, the roar of aircraft, the babble of voices shouting in strange tongues and the infants hollering all made for a surreal assault on the senses.”1 Three days before Christmas the ‘final assault’ was launched and what remained of Biafra was finally sliced in two. -

Cover Artwork on Separate File

COVER ARTWORK ON SEPARATE FILE THE ROYAL BOROUGH OF KINGSTON UPON THAMES ENRICHING KINGSTON UPON THAMES First recorded in a Royal Charter in 838, the medieval market town of Kingston is Britain’s oldest Royal Borough. It has a colourful history that includes the coronation of Saxon Kings and the construction of London’s oldest bridge, while present-day Kingston has become one of the capital’s most exclusive and desirable places to live. Today’s Kingston is a lively and picturesque market town, perfectly situated on the banks of the Thames, and with a character of its own, although Central London is just a train ride away. The latest addition to Kingston is Royal Exchange, an exciting new development built around the beautiful Grade II listed Old Post Office and Telephone Exchange buildings. It will offer 267 Manhattan, one, two and three bedroom apartments, adding a modern touch to complement Kingston’s evolving heritage. 3 There are two Grade II listed buildings at Royal Exchange. The Old Post Office, which dates back to 1875, and the Telephone Exchange, built in 1908. Both were once the beating heart of Kingston: bustling institutions that played host to generations A PART OF of workers. The Telephone Exchange eventually became a sorting HISTORY office in 1938 and closed in 1984, followed by the Old Post Office in 1995. But today, their restoration finally returns these two much-loved local landmarks to their former glory. The Telephone Exchange building will become a hub for businesses and exciting new ventures that will add KINGSTON HAS AN ABUNDANCE OF HISTORY an invigorating creative energy and new opportunities WITH OVER 300 LISTED BUILDINGS. -

FALL 2015 - Volume 62, Number 3

FALL 2015 - Volume 62, Number 3 WWW.AFHISTORICALFOUNDATION.ORG Fall 2015 -Volume 62, Number 3 WWW.AFHISTORICALFOUNDATION.ORG Features A War Too Long: Part II John S. Schlight 6 New Sandys in Town: A–7s and Rescue Operations in Southeast Asia Darrel Whitcomb 34 Ivory and Ebony: Officer Foes and Friends of the Tuskegee Airmen Daniel L. Haulman 42 Dragons on Bird Wings: The Combat History of the 812th Fighter Air Regiment By Vlad Antipov & Igor Utkin Review by Golda Eldridge 50 Richthofen: The Red Baron in Old Photographs By Louis Archard Review by Daniel Simonsen 50 The Ardennes, 1944-1945: Hitler’s Winter Offensive Book Reviews By Christer Bergström Review by Al Mongeon 50 The Medal of Honor: A History of Service Above and Beyond By Boston Publishers, ed. Review by Steven D. Ellis 51 American Military Aircraft 1908-1919 By Robert B. Casari Review by Joseph Romito 51 Believers in the Battlespace: Religion, Ideology and War By Peter H. Denton, ed. Review by R. Ray Ortensie 52 British Airship Bases of the Twentieth Century By Malcolm Fife Review by Carl J. Bobrow 53 The Phantom in Focus: A Navigator’s Eye on Britain’s Cold War Warrior By David Gledhill Review by Mike R. Semrau 53 Lords of the Sky By Dan Hampton Review by Janet Tudal Baltas 54 An American Pilot with the Luftwaffe: A Novella and Stories of World War II By Robert Huddleston Review by Steve Agoratus 54 The Astronaut Wives Club By Lily Koppel Review by Janet Tudal Baltas 55 Malloch’s Spitfire: The Story and Restoration of PK 350 By Nick Meikle Review by Steve Agoratus 56 U.S. -

A Decade of Civil Aviation in Zimbabwe: Towards a History of Air Zimbabwe Corporation 1980 to 1990

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Zambezia (1995), XXII (i). A DECADE OF CIVIL AVIATION IN ZIMBABWE: TOWARDS A HISTORY OF AIR ZIMBABWE CORPORATION 1980 TO 1990 A. S. MLAMBO Department of Economic History, University of Zimbabwe Abstract In 1980 when Air Zimbabwe was established, there was great hope that it would prosper, especially since it was going to operate in a global atmosphere without the restrictions of economic sanctions that had constrained its predecessor, Rhodesia Airways. In the first few years, Air Zimbabwe expanded its services, replaced old aircraft with newer and more hiel-efficient state-of- the-art aeroplanes. By the mid-1980s however, the airline had started to lose money and continued to do so for the rest of the decade, necessitating hefty subsidies from the government. This article traces the development of Air Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1990 and attempts to analyze the reasons behind the airline's disappointing performance. It suggests that the failure of the airline to operate as a viable commercial enterprise was a result of both internal weaknesses of the airline's administration and restrictive government policies, as well as a generally difficult global economic climate. INTRODUCTION Air Zimbabwe Corporation (hereafter called AirZim) was established under the Zimbabwe Corporation Act (Chapter 253) of 1980.1 The new airline took over from Rhodesia Airways which had been established in 1967 and which had operated profitably throughout its existence, with the exception of the 1979 financial year when it registered its first deficit. -

“Honoured More in the Breach Than in the Observance”: Economic Sanctions on Rhodesia1 and International Response, 1965 to 1979

“HONOURED MORE IN THE BREACH THAN IN THE OBSERVANCE”: ECONOMIC SANCTIONS ON RHODESIA1 AND INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE, 1965 TO 1979 A. S. Mlambo Department of Historical and Heritage Studies University of Pretoria Abstract The United Nations Security Council passed a series of resolutions condemning Rhodesia’s unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) in 1965, culminating in Resolution 253 of 1968 imposing comprehensive mandatory international sanctions on Rhodesia. With a few exceptions, notably South Africa and Portugal, most member states supported the resolution and pledged their commitment to uphold and enforce the measures. Yet, most countries, including those at the forefront of imposing sanctions against Rhodesia, broke sanctions or did little to enforce them. An examination of the records of the Security Council Committee Established in Pursuance of Resolution 253 (1968) Concerning the Question of Southern Rhodesia (the Sanctions Committee) shows that sanctions against Rhodesia were honoured more in the breach than in the observance. Keywords: Sanctions, UDI, United Nations, Security Council, Sanctions busting, Ian Smith, Harold Wilson Introduction On November 11, 1965, the Rhodesia Front Government of Prime Minister Ian Douglas Smith unilaterally declared independence (UDI) from Britain in response to the colonial authority’s reluctance to grant independence to the country under white minority rule. Facing mounting pressure to use force to topple the illegal regime in Rhodesia from the Afro-Asian lobby at the United Nations (UN), Britain opted, to impose economic sanctions on Rhodesia, instead. British Prime Minister Harold Wilson confidently predicted at the time 1 The names Rhodesia and Southern Rhodesia are used interchangeably in this paper. While the UDI leaders referred to the country only as ‘Rhodesia’, the United Nations continued to call it ‘Southern Rhodesia’ throughout the UDI period. -

Puuns 1 9 7 8 0 0 1 Vol 1

S/1 2529/Rev.1 S/1 2529/Rev.1 TENTH REPORT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL COMMITTEE ESTABLISHED IN PURSUANCE OF RESOLUTION 253 (1968) CONCERNING THE QUESTION OF SOUTHERN RHODESIA SECURITY COUNCIL OFFICIAL RECORDS THIRTY-THIRD YEAH SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT No. 2 Volume I UNITED NATIONS New York, 1978 NOTE Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. Documents of the Security Council (symbol SI...) are normally published in quarterly Supplements of the Official Records of the Security Council. The date of the document indicates the supplement in which it appears or in which information about it is riven. The resolutions of the Security Council, numbered in accordance with a system adopted in 1964, are published in yearly volumes of Resolutions and Decisions of the Security Council. The new system, which has been applied retroactively to resolutions adopted before 1 January 1965, became fully operative on that date. S/12529/Rev.l CONTENTS VOLUME I INTRODUCTION ........................... Chapter I. WORK OF THE COMMITTEE ................... Paragraphs 1-3 4 - 102 A. Organization and programme of work ... ........... ...5 - 24 (a) Working procedures ...... ................ .. 7 - 15 (b) Consideration of general subjects .. ......... ...16 - 24 B. Consideration of cases carried over from previous reports and new cases concerning possible violation of sanctions ......... ....................... ...25 - 98 (a) General cases ....... ................... ...31 - 86 (b) Cases opened on the basis of information supplied by individuals and non-governmental organizations (Case No. INGO-) ...... ................. ...87 - 93 (c) Imports of chrome, nickel and other materials from Southern Rhodesia into the United States of America (Case No. -

March 2019 and Their Music

Issue 89 Mar2019 FREE SLAP Supporting Local Arts & Performers WORCESTER’S NEW INDEPENDENT ITALIAN RESTAURANT Traditional Italian food, cooked the Italian way! We create all dishes in our kitchen, using only the finest quality fresh ingredients. f. t. i. SUGO at The Lamb & Flag SUGO at Friar St 30 The Tything 19-21 Friar Street, Worcester Worcester WR1 1JL WR1 2NA 01905 729415 01905 612211 [email protected] [email protected] Hello and welcome to the March issue of Slap Magazine, and a bumper issue it is too. 56 pages packed with local arts news, views, reviews and previews. Hopefully enough to keep you interested throughout the month. February was an exciting month for us. It started brightly with Independent Venue Week and a visit from 6Music’s Steve Lamacq helping to raise the profile of an already thriving local music scene. Check out our own Geoffrey Head’s pictorial highlights of a week of IVW gigs in our Mar 2019 centre spread. The month ended even brighter with an early Spring to get us in the festival mood. As the festivals are beginning to SLAP MAGAZINE announce their line ups we take a look at Lechlade and Unit 3a, Lowesmoor Wharf, Fusion, showing just how diverse the scene can be with many more to follow over the coming months. Worcester WR1 2RS Telephone: 01905 26660 Spoken word, Poetry and Comedy are also well covered within these pages, with something here for everyone. So [email protected] why not make the most of it folks, go to a show, an EDITORIAL exhibition, a viewing or even a gig in the pub, there’s over six Mark Hogan - Editor hundred to choose from in this area alone! Kate Cox - Arts Editor Sub Editors - Jasmine Griffin, Emily Branson, Over the last year or so we've had numerous enquiries Katie Harris, Helen Mole from people about subscribing to Slap Mag to be delivered Proof Reading - Michael Bramhall to their door. -

Joanna Warson Phd FINAL 2013

France in Rhodesia: French policy and perceptions throughout the era of decolonisation Joanna Warson This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth 2013 i Abstract This thesis analyses French policies towards and perceptions of the British colony of Rhodesia, from the immediate aftermath of the Second World War up until the territory’s independence as Zimbabwe in 1980. Its main objective is to challenge notions of exceptionality associated with Franco- African relations, by investigating French engagement with a region outside of its traditional sphere of African influence. The first two chapters explore the development of Franco-Rhodesian relations in the eighteen years following the establishment of a French Consulate in Salisbury in 1947. Chapter One examines the foreign policy mind-set that underpinned French engagement with Rhodesia at this time, whilst Chapter Two addresses how this mind-set operated in practice. The remaining three chapters explore the evolution of France’s presence in this British colony in the fourteen and a half years following the white settlers’ Unilateral Declaration of Independence. Chapter Three sets out the particularities of the post-1965 context, in terms of France’s foreign policy agenda and the situation on the ground in Central Southern Anglophone Africa. Chapter Four analyses how the policies of state and non-state French actors were implemented in Rhodesia after 1965, and Chapter Five assesses the impact of these policies for France’s relations with Africa, Britain and the United States, as well as for the end of European rule in Rhodesia. -

October 5 & 6, 2015

OCTOBER 5 & 6, 2015 GREETINGS FROM DELTA STATE PRESIDENT WILLIAM N. LAFORGE Welcome to Delta State University — in the heart of the Mississippi Delta region — which features a rich heritage of culture and music. Delta State proudly provides a superb college education and environment for its students. We offer a wide array of educational, cultural, and athletic activities. Our university plays a key role in the leadership and development of the Mississippi Delta and of the State of Mississippi through a variety of partnerships with businesses, local governments, and community organizations. We are a university of champions — in the classroom with talented faculty who focus on student instruction and mentoring; through award-winning degree programs in business, arts and sciences, nursing, and education; with unique, cutting-edge programs such as aviation, geospatial studies, and the Delta Music Institute; in intercollegiate athletics where we proudly boast national and conference championships in many sports; and, with a full package of extracurricular activities and a college experience that help prepare our students for careers in an ever-changing, global economy. Delta State University’s annual International Conference on the Blues consists of two days of intense academic and scholarly activity, and includes a variety of musical performances to ensure authenticity and a direct connection to the demographics surrounding the “Home of the Delta Blues.” The conference program includes academic papers and presentations, solicited from young and emerging scholars, and Blues performances to add appeal for all audiences. Delta State University’s International Conference on the Blues is a key component of the International Delta Blues Project, which also includes the development of a blues studies curriculum and the creation of a Blues Leadership Business Incubator, which will align with GRAMMY Museum Mississippi, opening in 2016. -

FOR SALE Town Centre Development Opportunity

FOR SALE Town Centre Development Opportunity With Planning Permission The Fighting Cocks, 56 Old London Road, Kingston Upon Thames, KT2 6QA KINGSTON OFFICE AGENT KEY SUMMARY Warwick Lodge Kieran McKeogh • Development opportunity 75-77 Old London Road [email protected] • Town centre location Kingston • Existing bar/music venue KT2 6ND • Planning permission Warwick Lodge, 75-77 Old London Road, Kingston Upon Thames, KT2 6ND Providing guaranteed commercial property solutions across Surrey, Middlesex, South and West London from our office in Kingston The Fighting Cocks, 56 Old London Road, Kingston upon Thames, KT2 6QA LOCATION RATES The property is located between both Old London The current rateable value is £62,300 resulting in Road and Fairfield North. The latter is part of the an amount of rates payable for the year ring road around Kingston, along which the 2017/2018 of £29,281. The rates should be majority of vehicular traffic is routed through the verified through the local rating authority LB town centre. Kingston. The property is on the eastern fringes of Kingston town centre, approximately 400 metres to the PRICE east of Clarence Street. Old London Road has The property will be sold via a sale of the company, improved as a retail location in Kingston town The Fighting Cocks Bar & Venue Ltd (Company no. centre in the last few years and is where a number 06061778) as a going concern of which the of the town’s independent retailers are located. property (Title no. SGL68100) is the sole asset. The Multiple retailers in Old London Road include guide price is £2,000,000.