Listening for Detroit Radio History with the Vertical File Carleton Gholz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

River Days Application 2016

FOOD VENDOR APPLICATION 2016 GM River Days 2016 Friday, June 24: 11am – 11pm Saturday, June 25: 11am – 11pm Sunday, June 26: 11am – 9pm ABOUT RIVER DAYS The Detroit RiverFront Conservancy is pleased to present the tenth annual River Days Festival, on Detroit’s internationally acclaimed RiverWalk. In 2015, 150,000 guests enjoyed activities and music that were as diverse as the attendees themselves. River Days takes place at the foot of the Renaissance Center, home to 30,000 employees including a thriving General Motors, and stretches down the RiverWalk to the Milliken State ParK. EVENT COMPONENTS As a unique celebration of the Detroit River and the three-mile RiverWalk, the Festival serves as a regional opportunity to showcase Detroit’s culture and environment. This year, River Days is scheduled to feature: • Three Live music stages including a national talent stage. • Interactive Kids’ Area produced by Detroit’s own Parade Company, located throughout Rivard Plaza adjacent to beautiful Milliken State Park. • The Diamond Jack ferry boat, offering tours of the Detroit River. • Sand sculptures and sand play area for kids. • Jet-ski exhibitions. • Coast Guard Vessels and Rescue Demonstrations. • A family-themed Carnival, games and activities. • Strolling entertainers along the RiverWalk. BENEFITS OF PARTICIPATION • Earn revenue – sell your food items to expected crowds of more than 150,000 guests. • Marketing – generate awareness of your food operation and develop clientele for long after the event is over. Marketing opportunities include: the option to distribute promotional materials at your booth (i.e., coupons, giveaways, etc.), the chance to make live radio appearances, and the opportunity to participate in media interviews. -

Radio Stations in Michigan Radio Stations 301 W

1044 RADIO STATIONS IN MICHIGAN Station Frequency Address Phone Licensee/Group Owner President/Manager CHAPTE ADA WJNZ 1680 kHz 3777 44th St. S.E., Kentwood (49512) (616) 656-0586 Goodrich Radio Marketing, Inc. Mike St. Cyr, gen. mgr. & v.p. sales RX• ADRIAN WABJ(AM) 1490 kHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-1500 Licensee: Friends Communication Bob Elliot, chmn. & pres. GENERAL INFORMATION / STATISTICS of Michigan, Inc. Group owner: Friends Communications WQTE(FM) 95.3 MHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-9500 Co-owned with WABJ(AM) WLEN(FM) 103.9 MHz Box 687, 242 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 263-1039 Lenawee Broadcasting Co. Julie M. Koehn, pres. & gen. mgr. WVAC(FM)* 107.9 MHz Adrian College, 110 S. Madison St. (49221) (517) 265-5161, Adrian College Board of Trustees Steven Shehan, gen. mgr. ext. 4540; (517) 264-3141 ALBION WUFN(FM)* 96.7 MHz 13799 Donovan Rd. (49224) (517) 531-4478 Family Life Broadcasting System Randy Carlson, pres. WWKN(FM) 104.9 MHz 390 Golden Ave., Battle Creek (49015); (616) 963-5555 Licensee: Capstar TX L.P. Jack McDevitt, gen. mgr. 111 W. Michigan, Marshall (49068) ALLEGAN WZUU(FM) 92.3 MHz Box 80, 706 E. Allegan St., Otsego (49078) (616) 673-3131; Forum Communications, Inc. Robert Brink, pres. & gen. mgr. (616) 343-3200 ALLENDALE WGVU(FM)* 88.5 MHz Grand Valley State University, (616) 771-6666; Board of Control of Michael Walenta, gen. mgr. 301 W. Fulton, (800) 442-2771 Grand Valley State University Grand Rapids (49504-6492) ALMA WFYC(AM) 1280 kHz Box 669, 5310 N. -

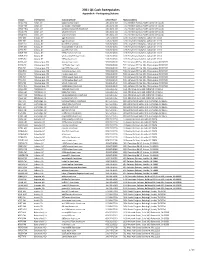

2021 Q1 Cash Sweepstakes Appendix a - Participating Stations

2021 Q1 Cash Sweepstakes Appendix A - Participating Stations Station iHM Market Station Website Office Phone Mailing Address WHLO-AM Akron, OH 640whlo.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-FM Akron, OH sunny1017.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-HD2 Akron, OH cantonsnewcountry.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WKDD-FM Akron, OH wkdd.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WRQK-FM Akron, OH wrqk.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WGY-AM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WGY-FM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WKKF-FM Albany, NY kiss1023.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WOFX-AM Albany, NY foxsports980.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WPYX-FM Albany, NY pyx106.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-FM Albany, NY 995theriver.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-HD2 Albany, NY wildcountry999.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WTRY-FM Albany, NY 983try.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 KABQ-AM Albuquerque, NM abqtalk.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM 87109 KABQ-FM Albuquerque, NM 1047kabq.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM -

Broadcasting Telecasting

YEAR 101RN NOSI1)6 COLLEIih 26TH LIBRARY énoux CITY IOWA BROADCASTING TELECASTING THE BUSINESSWEEKLY OF RADIO AND TELEVISION APRIL 1, 1957 350 PER COPY c < .$'- Ki Ti3dddSIA3N Military zeros in on vhf channels 2 -6 Page 31 e&ol 9 A3I3 It's time to talk money with ASCAP again Page 42 'mars :.IE.iC! I ri Government sues Loew's for block booking Page 46 a2aTioO aFiE$r:i:;ao3 NARTB previews: What's on tap in Chicago Page 79 P N PO NT POW E R GETS BEST R E SULTS Radio Station W -I -T -H "pin point power" is tailor -made to blanket Baltimore's 15 -mile radius at low, low rates -with no waste coverage. W -I -T -H reaches 74% * of all Baltimore homes every week -delivers more listeners per dollar than any competitor. That's why we have twice as many advertisers as any competitor. That's why we're sure to hit the sales "bull's -eye" for you, too. 'Cumulative Pulse Audience Survey Buy Tom Tinsley President R. C. Embry Vice Pres. C O I N I F I I D E I N I C E National Representatives: Select Station Representatives in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington. Forloe & Co. in Chicago, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Dallas, Atlanta. RELAX and PLAY on a Remleee4#01%,/ You fly to Bermuda In less than 4 hours! FACELIFT FOR STATION WHTN-TV rebuilding to keep pace with the increasing importance of Central Ohio Valley . expanding to serve the needs of America's fastest growing industrial area better! Draw on this Powerhouse When OPERATION 'FACELIFT is completed this Spring, Station WNTN -TV's 316,000 watts will pour out of an antenna of Facts for your Slogan: 1000 feet above the average terrain! This means . -

WDFN, WJLB, WKQI, WLLZ, WMXD, WNIC EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT June 1, 2020 - May 31, 2021

Page: 1/5 WDFN, WJLB, WKQI, WLLZ, WMXD, WNIC EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT June 1, 2020 - May 31, 2021 I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the "Master Recruitment Source List" ("MRSL") for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources ("RS") RS Referring Job Title Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree Outside Account Executive 1-5, 7, 9-11, 13 3 Outside Account Executive 2, 4-5, 8, 10, 13 8 Sales Support 2, 4-6, 10-11, 13 11 WKQI/Mojo In The Morning On Air/Digital Director 2, 4-5, 9-13 11 Automotive Account Executive 1, 9-11, 13 11 Page: 2/5 WDFN, WJLB, WKQI, WLLZ, WMXD, WNIC EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT June 1, 2020 - May 31, 2021 II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST ("MRSL") Source Entitled No. of Interviewees RS to Vacancy Referred by RS RS Information Number Notification? Over (Yes/No) Reporting Period All Access 28955 Pacific Coast Hwy Suite 210-5 Malibu, California 90265 1 Url : http://www.allaccess.com N 0 Career Services Manual Posting Direct Employers Association, Inc. 9002 N. Purdue Road Suite 100 Indianapolis, Indiana 46268 2 Phone : 866-268-6206 N 0 Email : [email protected] Fax : 1-317-874-9100 Job Board 3 Employee Referral N 1 iHeartMedia.dejobs.org 20880 Stone Oak Pkwy San Antonio, Texas 78258 4 Phone : 210-253-5126 N 0 Url : http://www.iheartmedia.dejobs.org Talent Acquisition Coordinator Manual Posting iHeartMediaCareers.com 20880 Stone Oak Pkwy San Antonio, Texas 78258 5 Phone : 210-253-5126 N 0 Url : http://www.iheartmediacareers.com Talent Acquisition Coordinator Manual Posting 6 Indeed.com - Not directly contacted by SEU N 1 7 LinkedIn - Not directly contacted by SEU N 1 8 LinkedIn-Not directly contacted by SEU N 1 Radio On-Line 3500 Tripp Avenue Amarillo, Texas 79121-1637 Phone : 806 352-7503 9 Url : http://www.radioonline.com N 0 Email : [email protected] Fax : 1-806-352-3677 Ron Chase Page: 3/5 WDFN, WJLB, WKQI, WLLZ, WMXD, WNIC EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT June 1, 2020 - May 31, 2021 II. -

Stations Coverage Map Broadcasters

820 N. Capitol Ave., Lansing, MI 48906 PH: (517) 484-7444 | FAX: (517) 484-5810 Public Education Partnership (PEP) Program Station Lists/Coverage Maps Commercial TV I DMA Call Letters Channel DMA Call Letters Channel Alpena WBKB-DT2 11.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOOD-TV 7 Alpena WBKB-DT3 11.3 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOTV-TV 20 Alpena WBKB-TV 11 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WXSP-DT2 15.2 Detroit WKBD-TV 14 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WXSP-TV 15 Detroit WWJ-TV 44 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WXMI-TV 19 Detroit WMYD-TV 21 Lansing WLNS-TV 36 Detroit WXYZ-DT2 41.2 Lansing WLAJ-DT2 25.2 Detroit WXYZ-TV 41 Lansing WLAJ-TV 25 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WJRT-DT2 12.2 Marquette WLUC-DT2 35.2 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WJRT-DT3 12.3 Marquette WLUC-TV 35 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WJRT-TV 12 Marquette WBUP-TV 10 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WBSF-DT2 46.2 Marquette WBKP-TV 5 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WEYI-TV 30 Traverse City-Cadillac WFQX-TV 32 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOBC-CA 14 Traverse City-Cadillac WFUP-DT2 45.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOGC-CA 25 Traverse City-Cadillac WFUP-TV 45 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOHO-CA 33 Traverse City-Cadillac WWTV-DT2 9.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOKZ-CA 50 Traverse City-Cadillac WWTV-TV 9 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOLP-CA 41 Traverse City-Cadillac WWUP-DT2 10.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOMS-CA 29 Traverse City-Cadillac WWUP-TV 10 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOOD-DT2 7.2 Traverse City-Cadillac WMNN-LD 14 Commercial TV II DMA Call Letters Channel DMA Call Letters Channel Detroit WJBK-TV 7 Lansing WSYM-TV 38 Detroit WDIV-TV 45 Lansing WILX-TV 10 Detroit WADL-TV 39 Marquette WJMN-TV 48 Flint-Saginaw-Bay -

New Solar Research Yukon's CKRW Is 50 Uganda

December 2019 Volume 65 No. 7 . New solar research . Yukon’s CKRW is 50 . Uganda: African monitor . Cape Greco goes silent . Radio art sells for $52m . Overseas Russian radio . Oban, Sheigra DXpeditions Hon. President* Bernard Brown, 130 Ashland Road West, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Notts. NG17 2HS Secretary* Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Treasurer* Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] MWN General Steve Whitt, Landsvale, High Catton, Yorkshire YO41 1EH Editor* 01759-373704 [email protected] (editorial & stop press news) Membership Paul Crankshaw, 3 North Neuk, Troon, Ayrshire KA10 6TT Secretary 01292-316008 [email protected] (all changes of name or address) MWN Despatch Peter Wells, 9 Hadlow Way, Lancing, Sussex BN15 9DE 01903 851517 [email protected] (printing/ despatch enquiries) Publisher VACANCY [email protected] (all orders for club publications & CDs) MWN Contributing Editors (* = MWC Officer; all addresses are UK unless indicated) DX Loggings Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] Mailbag Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Home Front John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB 01442-408567 [email protected] Eurolog John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB World News Ton Timmerman, H. Heijermanspln 10, 2024 JJ Haarlem, The Netherlands [email protected] Beacons/Utility Desk VACANCY [email protected] Central American Tore Larsson, Frejagatan 14A, SE-521 43 Falköping, Sweden Desk +-46-515-13702 fax: 00-46-515-723519 [email protected] S. -

Moving & Relocation Directory

Moving & Relocation Directory Ninth Edition A Reference Guide for Moving and Relocation, With Profi les for 121 U.S. Cities, Featuring Mailing Addresses, Local and Toll-Free Telephone Numbers, Fax Numbers, and Web Site Addresses for: • Chambers of Commerce, Government Offi ces, Libraries, and Other Local Information Resources (including Online Resources) • Suburban and Other Area Communities • Major Employers • Educational Institutions and Hospitals • Transportation Services • Utility and Local Telecommunications Companies • Banks and Shopping Malls • Newspapers, Magazines, and Radio & TV Stations • Attractions, Sports & Recreation and also Including Statistical, Demographic, and Other Data on Location, Climate and Weather, History, Economy, Education, Population, and Quality and Cost of Living Business Directories Inc 155 W. Congress, Ste. 200 Detroit, MI 48226 800-234-1340 • www.omnigraphics.com 1 Contents Please see page 4 for a complete list of the cities featured in this directory, together with references to the page on which each city’s listing begins. A state-by-state list of the cities begins on page 5. Abbreviations Used in This Directory . Inside Front Cover Introduction. 7 United States Time Zones Map . 10 Special Features 1. Where to Get Help For Moving . 12 2. Chambers of Commerce—City . 14 3. Chambers of Commerce—State . 17 4. Employment Agencies . 18 5. National Moving Companies . 24 6. Corporate Housing . 26 7. Self-Storage Facilities . 26 8. National Real Estate Companies . 27 9. State Realtors Associations . 28 10. Mileage Table . 30 11. Area Codes in State Order . 31 12. Area Codes in Numerical Order . 34 Moving & Relocation Directory . 37 Index of Cities & Counties . .1417 Radio Formats & Television Network Abbreviations . -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Staions WJR—Womanla WJT.B-News.WJBK- WJLB-Polish WJR

RA TheLight for Be FM sure for 2600 Now 44.9 1 I easy, ay >y 2100. Two Saturday, f •y. IT, Watch .... iJny night Meter. MEASURE you 6314 the MC 1400 NOW are {Coca(}) Detroit T.IM. Open W. 1419 Hear the on on DETROIT'S Twice (Tima hear 0:15 No your Program 12:30-8:15Eaton 0.1 800 Benny Jimmy American kd-fait! IYSTERT have .... ea p. Fine as »( this escape the your your c sponsoring Mystery Jan Red Harry Edison charge light the Evening! HOME ...tor S,i m. a C Cola RADIO • rapid NIGHT) PtISINTS right .... Broadway Tower FM TONIGHT! comfortable Listings. dial -e Famous November " - FREQUENCY Hew 8, Night rots Saids )relinquished fire Sunday. Much • with Goodman Soviet James • MeNicholt MODULATION LOG daily. Luncaferd • Company, phone g seeing. light great dial \ at WJLB Stations 1 jjjg 194| ]’wt/ighft EXHIBITION... I H W49D fl ¦ H ¦ R ¦ H J HBIB STUDYING SERLIN’S PHILCO STATION Detroit WJLB--W49D WJ WJ WJR CKLW WW’J WJR WWJ WJR WJR WJR WJR WJR WJR WJR WJR WJR WJR WJR WJR WJR WWJ ENTERTAINMENT WWJ WWJ WWJ WWJ WWJ WWJ WXYZ WWJ- WJ*— WJBK •WJUI WXTZ CKLW WJBK WJI.B WJBK WJI.B CKLVV WJBK WWJ- --WJBK WJI.B WXYZ WJLB WJLB WJI.B WJLB WJLB WJLB WWJ WJLB BK WWJ WJLB WWJ— 7 —«. WWJ- WXYZ WJBK WJBK WJBK WJR— WXYZ WJR— WXYZ WXTZ WJLB WXTZ WWJ— • CKLW CKLW CKLW WJLB WJR— CKLW WXYZ WJBK WXYZ WXYZ WXYZ • WJR— f 8 WJR— CKLW WJR— WWJ— i WJR— WJR— 5 WXTZ WXTZ CKLW- • WJR— WJR— * WWJ— WWJ— • WWJ— WWJ— WXTZ WWJ— • CJLLW— Ty U WWJ— t -Qui Wa CKLW— WXYZ-- it It WJBK- CKLW— It WJBK- CKLW- WXYZ— WJI.B— CKLW— WJBK- WJBK— CKLW— WXYZ- WJBK— CKLW— WWJ— WJBK- W’JBK— WJLB— WXYZ- CKLW— Ty WJBK- WJLB— CKLW- CKLW- It WJBK- CKLW— WJBK— l* WJLB— CKLW- WXYZ- WJLB— CKLW— WJBK— WJBK— js Lee WJBK— Bl* WJBK— CKLW— WJBK— MS :4f L. -

Media Bureau Call Sign Actions 11/15/2017

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission News Media Information 202-418-0500 445 12th St., S.W. Internet: http://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 Report No. 608 Media Bureau Call Sign Actions 11/15/2017 During the period from 10/01/2017 to 10/31/2017 the Commission accepted applications to assign call signs to, or change the call signs of the following broadcast stations. Call Signs Reserved for Pending Sales Applicants Call Sign Service Requested By City State File-Number Former Call Sign KPJK DT RURAL CALIFORNIA BROADCASTING CORPORATION SAN MATEO CA 20171003ACI KCSM-TV KYDQ FM EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION ESCONDIDO CA 20170926AFF KSOQ-FM WKBP FM EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION BENTON PA 20170926AFG WGGI WLJV FM EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION SPOTSYLVANIA VA 20171010ABN WYAU New or Modified Call Signs Row Effective Former Call Call Sign Service Assigned To City State File Number Number Date Sign 1 10/01/2017 KQPV-LP FL ORIENTAL CULTURE CENTER WEST COVINA CA 20131114AWN New 2 10/01/2017 KQSG-LP FL THE EMPEROR'S CIRCLE OF SHEN YUN EL MONTE CA 20131114BOI New 3 10/01/2017 WCHB AM WMUZ RADIO, INC. ROYAL OAK MI WEXL 4 10/01/2017 WMUZ AM WMUZ RADIO, INC. TAYLOR MI WCHB BAL- 5 10/02/2017 KRRD AM OL TIMEY BROADCASTING, LLC FAYETTEVILLE AR KOFC 20170727AFB SALEM MEDIA OF MASSACHUSETTS, 6 10/03/2017 WFIA AM LOUISVILLE KY WJIE LLC DENNIS WALLACE, COURT-APPOINTED 7 10/03/2017 KVMO FM VANDALIA MO KKAC RECEIVER 1 8 10/04/2017 KCCG-LP FL CHURCH OF GOD-GREENVILLE, TX GREENVILLE TX 20131115ASY New BORDERLANDS COMMUNITY MEDIA 9 10/06/2017 KISJ-LP FL BISBEE AZ 20131113BNS New FOUNDATION, INC.