Impact of Glacier Melt in Alaska on the Population of Local Animals and the Inuit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inuit People

Inuit People Most of these objects were made in the 19th century by the Inuit, whose name means ‘the people’. The Athabascans called their Inuit neighbours ‘Eskimo’ meaning ‘eaters of raw flesh’. The Inuit way of life was adapted to their harsh territory which stretched 6000 miles across the Arctic from the Bering Sea to Greenland. Carving 80 Chisel handle made from bone with a carved face and animal figures. Possibly from south Alaska, made before 1880. 81 Carrying strap made of hide with a carved stone toggle, made in the 19th century. 82 Smoking pipe made of ivory and decorated with whaling scenes. Made by the western Inuit in the late 19th century. 83 Ivory toggle carved in the form of a seal. Probably made by the western Inuit before 1854. 84 Ivory toggle carved in the form of a bear. Probably made by the western Inuit before 1854. Hunting 85 Snow goggles made of wood. Used in the snow like sun glasses to protect the eyes. Made by the central Inuit before 1831. 86 Bolas made of ivory balls and gut strips, from Cape Lisburn, Bering Strait, made before 1848. Thrown when hunting to entangle a bird or other quarry. 87 Harpoon head, probably for a seal harpoon. Made by the western Inuit in the 19th century. 88 Seal decoy made of wood with claws. It was Used to scratch the ice. The sound attracted seals to breathing holes. Probably made by the western Inuit in the late 19th century. 89 Bone scoop used for clearing seal breathing holes in the ice, made in the 19th century. -

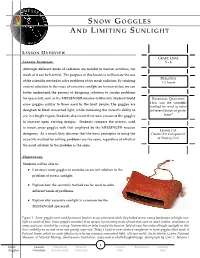

Snow Goggles and Limiting Sunlight

MESS E N G E R S NOW G O ggl ES Y R U A ND L IMITIN G S UN L I G HT C R E M TO N M I S S I O L E S S O N O V E RV I E W GRADE LEVEL L ESSON S UMMARY 5 - 8 Although different kinds of radiation are helpful to human activities, too much of it can be harmful. The purpose of this lesson is to illustrate the use DURATION of the scientific method to solve problems of too much radiation. By studying 1-2 hours ancient solutions to the issue of excessive sunlight on human vision, we can better understand the process of designing solutions to similar problems for spacecraft, such as the MESSENGER mission to Mercury. Students build ESSENTIAL QUESTION snow goggles similar to those used by the Inuit people. The goggles are How can the scientific method be used to solve designed to block unwanted light, while increasing the viewer’s ability to different kinds of prob- see in a bright region. Students also create their own version of the goggles lems? to improve upon existing designs. Students compare the process used to invent snow goggles with that employed by the MESSENGER mission Lesson 2 of designers. As a result, they discover that the basic principles of using the Grades 5-8 Component scientific method for solving problems are the same, regardless of whether of Staying Cool the exact solution to the problem is the same. O BJECTIVES Students will be able to: ▼ Construct snow goggles to examine an ancient solution to the problem of excess sunlight. -

Tuesday: Igloo Topic Why Can’T Penguins and Polar Bears Be Let’S Learn How to Build an Igloo Neighbours?

Monday: Inuit Snow Goggles Reception Spring Term 1 Week 5 Tuesday: Igloo Topic Why can’t penguins and Polar Bears be Let’s learn how to build an igloo Neighbours? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R-x5QOSqP3E The Arctic is not only cold, but the snow is also blinding. To prevent snow glare, the Inuit created snow goggles. The goggles were This week we are learning about Inuits. What would it be like to stay in an igloo? Use junk typically made out of bone or wood, and contain modelling to make an igloo. It could be large enough a slit across the eyes, just large enough to see Please complete one lesson per day. Please upload for your teddies to sit in or you could make one big through. Have a go at making some use card onto Tapestry and title it e.g. enough for you to sit in! and cut slits for the eyes. Wednesday:Inuksuk Thursday: Art Friday: PE Artist- Ted Harrison Winter Workout Watch Miss Ely’s lesson on Tapestry. Inuksuk means "a thing that can act in the place of a human being". They were used by Inuits to communicate many things such as https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=buZMJAWbY1s the best way to travel, best fishing areas, Get warm with this winter work out. You can warn of dangerous places, to show where make your own exercises up too! food is stored, to remember people or Ted Harrison was a British- Canadian artist who events, and to help hunt caribou. Have a go created colourful landscape paintings. -

Smithsonian at the Poles Contributions to International Polar Year Science

A Selection from Smithsonian at the Poles Contributions to International Polar Year Science Igor Krupnik, Michael A. Lang, and Scott E. Miller Editors A Smithsonian Contribution to Knowledge WASHINGTON, D.C. 2009 This proceedings volume of the Smithsonian at the Poles symposium, sponsored by and convened at the Smithsonian Institution on 3–4 May 2007, is published as part of the International Polar Year 2007–2008, which is sponsored by the International Council for Science (ICSU) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Published by Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press P.O. Box 37012 MRC 957 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 www.scholarlypress.si.edu Text and images in this publication may be protected by copyright and other restrictions or owned by individuals and entities other than, and in addition to, the Smithsonian Institution. Fair use of copyrighted material includes the use of protected materials for personal, educational, or noncommercial purposes. Users must cite author and source of content, must not alter or modify content, and must comply with all other terms or restrictions that may be applicable. Cover design: Piper F. Wallis Cover images: (top left) Wave-sculpted iceberg in Svalbard, Norway (Photo by Laurie M. Penland); (top right) Smithsonian Scientifi c Diving Offi cer Michael A. Lang prepares to exit from ice dive (Photo by Adam G. Marsh); (main) Kongsfjorden, Svalbard, Norway (Photo by Laurie M. Penland). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithsonian at the poles : contributions to International Polar Year science / Igor Krupnik, Michael A. Lang, and Scott E. Miller, editors. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-9788460-1-5 (pbk. -

Proquest Dissertations

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Role of Fur Trade Technologies in Adult Learning: A Study of Selected Inuvialuit Ancestors at Cape Krusenstern, NWT (Nunavut), Canada 1935-1947 by David Michael Button A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF EDUCATION GRADUATE DIVISION OF EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH CALGARY, ALBERTA August 2008 © David Button 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44376-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44376-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

WHO ARE the INUIT? a Conversation with Qauyisaq “Kowesa” Etitiq

WHO ARE THE INUIT? A conversation with Qauyisaq “Kowesa” Etitiq Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario Elementary Teachers' Federation of Ontario (ETFO) 136 Isabella Street, Toronto, ON M4Y 0B5 416-962-3836 or 1-888-838-3836 etfo.ca ETFOprovincialoffice @ETFOeducators @ETFOeducators Copyright © July 2020 by ETFO ETFO EQUITY STATEMENT It is the goal of the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario to work with others to create schools, communities and a society free from all forms of individual and systemic discrimination. To further this goal, ETFO defines equity as fairness achieved through proactive measures which result in equality, promote diversity and foster respect and dignity for all. ETFO HUMAN RIGHTS STATEMENT The Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario is committed to: • providing an environment for members that is free from harassment and discrimination at all provincial or local Federation sponsored activities; • fostering the goodwill and trust necessary to protect the rights of all individuals within the organization; • neither tolerating nor condoning behaviour that undermines the dignity or self-esteem of individuals or the integrity of relationships; and • promoting mutual respect, understanding and co-operation as the basis of interaction among all members. Harassment and discrimination on the basis of a prohibited ground are violations of the Ontario Human Rights Code and are illegal. The Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario will not tolerate any form of harassment or discrimination, as defined by the Ontario Human Rights Code, at provincial or local Federation sponsored activities. ETFO LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT In the spirit of Truth and Reconciliation, the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario acknowledges that we are gathered today on the customary and traditional lands of the Indigenous Peoples of this territory. -

NTI IIBA for Conservation Areas Cultural Heritage and Interpretative

NTI IIBA for Phase I: Cultural Heritage Resources Conservation Areas Report Cultural Heritage Area: McConnell River and Interpretative Migratory Bird Sanctuary Materials Study Prepared for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 1 May 2011 This Cultural Heritage Report: McConnell River Migratory Bird Sanctuary (Arviat) is part of a set of studies and a database produced for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. as part of the project: NTI IIBA for Conservation Areas, Cultural Resources Inventory and Interpretative Materials Study Inquiries concerning this project and the report should be addressed to: David Kunuk Director of Implementation Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 3rd Floor, Igluvut Bldg. P.O. Box 638 Iqaluit, Nunavut X0A 0H0 E: [email protected] T: (867) 975‐4900 Project Manager, Consulting Team: Julie Harris Contentworks Inc. 137 Second Avenue, Suite 1 Ottawa, ON K1S 2H4 Tel: (613) 730‐4059 Email: [email protected] Cultural Heritage Report: McConnell River Migratory Bird Sanctuary (Arviat) Authors: Philip Goldring, Consultant: Historian and Heritage/Place Names Specialist (primary author) Julie Harris, Contentworks Inc.: Heritage Specialist and Historian Nicole Brandon, Consultant: Archaeologist Luke Suluk, Consultant: Inuit Cultural Specialist/Archaeologist Frances Okatsiak, Consultant: Collections Researcher Note on Place Names: The current official names of places are used here except in direct quotations from historical documents. Throughout the document Arviat refers to the settlement established in the 1950s and previously known as Eskimo Point. Names of -

Applying Community-Based Approaches to an Archaeology of Banks Island, NWT

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-12-2016 12:00 AM There Is More Than One Way to Do Something Right: Applying Community-Based Approaches to an Archaeology of Banks Island, NWT Laura Elena Kelvin The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Lisa Hodgetts The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Anthropology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Laura Elena Kelvin 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Kelvin, Laura Elena, "There Is More Than One Way to Do Something Right: Applying Community-Based Approaches to an Archaeology of Banks Island, NWT" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 4168. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/4168 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This dissertation explores how historical knowledge is produced and maintained within the Inuvialuit (Western Arctic Inuit) community of Sachs Harbour, NWT, to determine how archaeological research can best complement and respect Inuvialuit understandings and ways of knowing the past. When archaeologists apply Indigenous knowledges to their research they often have limited understandings of how these knowledges work, and may apply them inadequately or inappropriately. I employ an archaeological ethnographic approach to help Ikaahukmiut (people with ties to Banks Island, NWT) articulate to archaeologists how they construct their knowledge of Banks Island’s past. -

Diverse Peoples – Aboriginal Contributions and Inventions C

2.2.1 Diverse Peoples – Aboriginal Contributions and Inventions c CANOES – Canoes made of UPSET STOMACH bark and pitch varied greatly CORN – Corn is a staple food REMEDIES – A tea made with in size, depending on what that was cultivated by the entire blackberry plant they were needed for. Today’s Aboriginal people for was used for a number of recreational canoe is thousands of years. Today, sicknesses, including fashioned after this corn is a vital, hardy, and dysentery, cholera, and upset Aboriginal invention, and it, high-yielding plant that can stomach. Eating the actual along with the kayak, is grow practically everywhere berry or drinking its juice was unsurpassed throughout the in the world. also an effective way to world for travelling over control diarrhea. shallow or difficult waterways. PETROLEUM JELLY – DART GAME – Some Aboriginal people discovered LACROSSE – Aboriginal Aboriginal people created the petroleum jelly and used it to people played hundreds of game of lawn darts, using moisten and protect animal outdoor team sports. Lacrosse shucked new green corn with and human skin. It was also is a team sport invented by its kernels removed. Feathers used to stimulate healing. This Aboriginal people, which many were attached to the darts, skin ointment is one of the believe is the forerunner to which were tossed at targets most popular in the world hockey. on the ground. today. COUGH SYRUP – Many Aboriginal people throughout SNOWSHOES – Aboriginal WILD RICE – Wild rice is Canada developed unique people developed technology actually a delicious and prized combinations of wild plants to for travel over snow. -

Final Gr 1-3 Return

Light: The Return of the Sun A Two-Way Science Learning Unit for Qikiqtani Lower Elementary (Grades 1-3) Students University of Manitoba Centre for Research, Youth, Science Teaching and Learning July 2008 Table of Contents Topic Page Guiding Principles of the Unit 3 Cross-Curricular Applications 4 Conceptual Ideas and Progression 5 Skills Development 8 Attitudes and Beliefs Development 9 Curriculum Applications 10 Things to Consider in Preparing to Teach the Unit 12 About the Activities 13 Activities 14 Stories to Tell Immediately before the Return of the Sun 97 Cover Image: Kenojuak Ashevak’s The Woman Who Lives in the Sun. Stonecut in red on laid Japan paper. West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative, 1960. 2 Guiding Principles of the Unit • Provide two-way learning experiences by integrating Inuit knowledge, ways of knowing, beliefs and values and contemporary scientific knowledge, processes and attitudes. • Draw upon traditional and contemporary Inuit cultural examples as contexts for student learning. • Include the local community and its people in students’ learning opportunities as the classroom is an extension of the school and local community. • Foster language development in Inuktitut and, where required or encouraged, English. • Use diagnostic and formative assessment to inform planning and teaching and monitor student learning. • Engage students by starting lessons by providing first-hand experiences for students or drawing upon common experience. • When using story to engage students, use the interrupted-story-line as a vehicle to prompt questioning first-hand investigations. • Deliberately promote scientific attitudes of mind (curiosity, problem- solving, working to end) student through thoughtful independent consideration of questions and challenges posed. -

From an Ethnobotanical Perspective

Conservation Value of the North American Borealfrom an Ethnobotanical Forest Perspective Author About the David Suzuki Foundation amanda Karst the David suzuki foundation works with government, business, and individuals a report commissioned by the Canadian to conserve our environment through Boreal initiative, the David suzuki science-based education, advocacy, and foundation, and the Boreal songbird policy work, and acting as a catalyst for initiative social change. the foundation’s main goals include ensuring that Canada does Author bio its fair share to avoid dangerous climate amanda Karst lives in Winnipeg and is change; protecting the diversity and a research associate at the Centre for health of Canada’s marine, freshwater, indigenous environmental resources and terrestrial wildlife and ecosystems; (Cier). her work at Cier has involved and making sure that Canadians can watershed planning, traditional foods maintain a high quality of life within the and medicines, climate change, and finite limits of nature through efficient environmental monitoring. amanda is resource use. for more information visit: métis, originally from saskatchewan. www.davidsuzuki.org Before working at Cier, she worked on a number of projects in About the Boreal Songbird Initiative ethnobotany and plant ecology in British the Boreal songbird initiative (Bsi) is Columbia, saskatchewan, Quebec a non-profit organization dedicated to and newfoundland and labrador. raising awareness, through science, she obtained her m.sc. in biology education, and outreach, of the (ethnobotany/plant ecology) from the importance of the Canadian Boreal university of victoria in 2005. forest to north america’s birds, other wildlife, and the global environment. Acknowledgements for more information visit: the author would like to thank alestine www.borealbirds.org andre, Kelly Bannister, stuart Crawford, ann Garibaldi, Cheryl Jerome, marla Suggested citation robson and nancy turner for their Karst, a. -

Junior Ranger, Iñupiat Heritage Center

The Iñupiat Heritage Center & The National Park Service Become a Junior Ranger! Junior Ranger Instructions Welcome to the Iñupiat Heritage Center! This booklet will help you understand the exhibits at the Heritage Center and learn more about Iñupiat language and traditions. As a Junior Ranger, be alert on your walk through the Center and try to answer as many questions in this booklet as you can. Be sure to ask lots of questions, read the labels and displays, and observe everything around you. When your tour of the Heritage Center is over, come back to the front desk and show your finished booklet to the receptionist, and you will be rewarded for your hard work! Good luck, and have fun! Courtesy Alaska Native Knowledge Network Toggle-headed harpoon Drawing by Mark Luttrell Northern Eskimo whalebone Photo by John Robson mask. Drawing by Mark Luttrell On the front cover, back row, from left to right: Lesley Hopson, Brian Ahkivianna, Stephanie Hopson, Alex Kaleak, Mary Booth. In front: Marilyn Booth. Umiaq Activity Label the different parts of the umiaq in Iñupiaq or in English. If you need help, go to the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission (AEWC) Exhibit and look at the umiaq exhibit. Rib: tulimaaq Stern: aqu Bow: sivu Keel: kuyaaq Skin covering: amiq Skin’s lashing ropes: tuurrun Umiaq. Drawing by Mark Luttrell, 2002 Umiaq Activity Find the lead in the ice and follow it to the whale! Bowhead Whale Activity Abviq Activity Write the Iñupiaq name of the whale’s body part next to the correct arrow. Key Baleen suqqaq Blowhole qifaq Flipper talibuq Fluke aqikkaq Eye iri Bowhead Whales weight up to 60 tons and up to 60 feet in length.