Alaska Native Local and Traditional Knowledge Inventory and Bibliographic Data Base Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

07 Inuktitut

WINTER UKIUQ HIVER srs6 wkw5 xgc5b6ym/q8i4 scsyc3i6 • GIVING VOICE TO THE INUIT EXPERIENCE w L’EXPRESSION DE L’EXPÉRIENCE INUITE • INUIT ATUQATTAQSIMAJANGINNIK UQAUSIQARNIQ 0707 Inuktitut w˚Zhxq8NMs6b¡ Live Life! Inuugasuanginnalauqta! Croquez la vie à belles dents! PM40069916 n6rb6 • ISSUE • NUMÉRO • SAQQITAQ 102 $6.25 o www.itk.ca swo ≈b7{ yNg kNK7j5 Willie Adams SENATOR FOR NUNAVUT sW3ΩD6X9oxo3u7m5 s winter turns dFxhAtco3b into spring let us yeis2 take the time to enjoy the return sst3X9oxixi4. A of the sun. wloq5 ❘ TABLE OF CONTENTS ❘ ILULINGIT ❘ TABLE DES MATIÈRES ci5gu: kNF7u c/3g3†5 scs0Jwiq5 wk8i4 m4f5gi4: w˚Zhxq8NMs6b¡ 40 Up Close: Kayak Adventurers Deliver Message to Inuit Youth: LIVE LIFE! Qanittumi: Nunavimmi Qajarturtiit Uqaujjuiningit Inunnik Makkuttunik: INUUGASUANGINNALAUQTA! De près: Des aventuriers voyageant en qayaq au Nunavik livrent un message aux jeunes Inuits : CROQUEZ LA VIE À BELLES DENTS! x0posZw5 5 ≈6r4hwps2 scsyq5 srs3b3gu s8k4f5 yM From the Editor’s Desk Through the Lens Aaqqiksuijiup saangannit 12 Rubrique de l’éditrice The Arctic Night Sky Ajjiliuqait 7 Nwˆ6ymJ5 Ukiurtartumi Unnukkut Sila In Brief Coup d’oeil Nainaaqsimajut Le ciel nocturne de l’Arctique En bref srs3b3©2 yMzb xy0p3X9oxiz 34 w4W8ixtbsiq5 W?9oxtbsJi5: wkFxlw5 X3NNw3X9oxo3iz w˚yzb x4g3bsMzixk5 Climate Change In The Arctic W?9oxtbsix3gi5 20 Ukiurtartuup silangata asijjirpallianinga Echoes of a Boom: Inuvialuit Brace for Next Wave Le changement climatique dans l’arctique of Social Impacts Ikpinniatitauningit pivalliatitaujunit: x4gLj6: wkw5 -

Inuit People

Inuit People Most of these objects were made in the 19th century by the Inuit, whose name means ‘the people’. The Athabascans called their Inuit neighbours ‘Eskimo’ meaning ‘eaters of raw flesh’. The Inuit way of life was adapted to their harsh territory which stretched 6000 miles across the Arctic from the Bering Sea to Greenland. Carving 80 Chisel handle made from bone with a carved face and animal figures. Possibly from south Alaska, made before 1880. 81 Carrying strap made of hide with a carved stone toggle, made in the 19th century. 82 Smoking pipe made of ivory and decorated with whaling scenes. Made by the western Inuit in the late 19th century. 83 Ivory toggle carved in the form of a seal. Probably made by the western Inuit before 1854. 84 Ivory toggle carved in the form of a bear. Probably made by the western Inuit before 1854. Hunting 85 Snow goggles made of wood. Used in the snow like sun glasses to protect the eyes. Made by the central Inuit before 1831. 86 Bolas made of ivory balls and gut strips, from Cape Lisburn, Bering Strait, made before 1848. Thrown when hunting to entangle a bird or other quarry. 87 Harpoon head, probably for a seal harpoon. Made by the western Inuit in the 19th century. 88 Seal decoy made of wood with claws. It was Used to scratch the ice. The sound attracted seals to breathing holes. Probably made by the western Inuit in the late 19th century. 89 Bone scoop used for clearing seal breathing holes in the ice, made in the 19th century. -

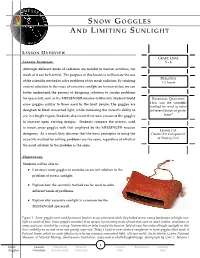

Snow Goggles and Limiting Sunlight

MESS E N G E R S NOW G O ggl ES Y R U A ND L IMITIN G S UN L I G HT C R E M TO N M I S S I O L E S S O N O V E RV I E W GRADE LEVEL L ESSON S UMMARY 5 - 8 Although different kinds of radiation are helpful to human activities, too much of it can be harmful. The purpose of this lesson is to illustrate the use DURATION of the scientific method to solve problems of too much radiation. By studying 1-2 hours ancient solutions to the issue of excessive sunlight on human vision, we can better understand the process of designing solutions to similar problems for spacecraft, such as the MESSENGER mission to Mercury. Students build ESSENTIAL QUESTION snow goggles similar to those used by the Inuit people. The goggles are How can the scientific method be used to solve designed to block unwanted light, while increasing the viewer’s ability to different kinds of prob- see in a bright region. Students also create their own version of the goggles lems? to improve upon existing designs. Students compare the process used to invent snow goggles with that employed by the MESSENGER mission Lesson 2 of designers. As a result, they discover that the basic principles of using the Grades 5-8 Component scientific method for solving problems are the same, regardless of whether of Staying Cool the exact solution to the problem is the same. O BJECTIVES Students will be able to: ▼ Construct snow goggles to examine an ancient solution to the problem of excess sunlight. -

Tuesday: Igloo Topic Why Can’T Penguins and Polar Bears Be Let’S Learn How to Build an Igloo Neighbours?

Monday: Inuit Snow Goggles Reception Spring Term 1 Week 5 Tuesday: Igloo Topic Why can’t penguins and Polar Bears be Let’s learn how to build an igloo Neighbours? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R-x5QOSqP3E The Arctic is not only cold, but the snow is also blinding. To prevent snow glare, the Inuit created snow goggles. The goggles were This week we are learning about Inuits. What would it be like to stay in an igloo? Use junk typically made out of bone or wood, and contain modelling to make an igloo. It could be large enough a slit across the eyes, just large enough to see Please complete one lesson per day. Please upload for your teddies to sit in or you could make one big through. Have a go at making some use card onto Tapestry and title it e.g. enough for you to sit in! and cut slits for the eyes. Wednesday:Inuksuk Thursday: Art Friday: PE Artist- Ted Harrison Winter Workout Watch Miss Ely’s lesson on Tapestry. Inuksuk means "a thing that can act in the place of a human being". They were used by Inuits to communicate many things such as https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=buZMJAWbY1s the best way to travel, best fishing areas, Get warm with this winter work out. You can warn of dangerous places, to show where make your own exercises up too! food is stored, to remember people or Ted Harrison was a British- Canadian artist who events, and to help hunt caribou. Have a go created colourful landscape paintings. -

A Circumpolar Reappraisal: the Legacy of Gutorm Gjessing (1906-1979)

A Circumpolar Reappraisal: The Legacy of Gutorm Gjessing (1906-1979) Proceedings of an International Conference held in Trondheim, Norway, 10th-12th October 2008, arranged by the Institute of Archaeology and Religious Studies, and the SAK department of the Museum of Natural History and Archaeology of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) Edited by Christer Westerdahl BAR International Series 2154 2010 Published by Archaeopress Publishers of British Archaeological Reports Gordon House 276 Ban bury Road Oxford 0X2 7ED England [email protected] www.archaeopress.com BAR S2154 A Circumpolar Reappraisal: The Legacy of Gutorm Gjessing (1906-1979). Proceedings of an International Conference held in Trondheim, Norway, 10th-12th October 2008, arranged by the Institute of Archaeology and Religious Studies, and the SAK department of the Museum of Natural History and Archaeology of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2010 ISBN 978 1 4073 0696 4 Front and back photos show motifs from Greenland and Spitsbergen. © C Westerdahl 1974, 1977 Printed in England by 4edge Ltd, Hockley All BAR titles are available from: Hadrian Books Ltd 122 Banbury Road Oxford 0X2 7BP England [email protected] www.hadrianbooks.co.uk The current BAR catalogue with details of all titles in print, prices and means of payment is available free from Hadrian Books or may be downloaded from www.archaeopress.com CHAPTER 7 ARCTIC CULTURES AND GLOBAL THEORY: HISTORICAL TRACKS ALONG THE CIRCUMPOLAR ROAD William W. Fitzhugh Arctic Studies Center, Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 2007J-J7072 fe// 202-(W-7&?7;./ai202-JJ7-2&&f; e-mail: fitzhugh@si. -

Smithsonian at the Poles Contributions to International Polar Year Science

A Selection from Smithsonian at the Poles Contributions to International Polar Year Science Igor Krupnik, Michael A. Lang, and Scott E. Miller Editors A Smithsonian Contribution to Knowledge WASHINGTON, D.C. 2009 This proceedings volume of the Smithsonian at the Poles symposium, sponsored by and convened at the Smithsonian Institution on 3–4 May 2007, is published as part of the International Polar Year 2007–2008, which is sponsored by the International Council for Science (ICSU) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Published by Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press P.O. Box 37012 MRC 957 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 www.scholarlypress.si.edu Text and images in this publication may be protected by copyright and other restrictions or owned by individuals and entities other than, and in addition to, the Smithsonian Institution. Fair use of copyrighted material includes the use of protected materials for personal, educational, or noncommercial purposes. Users must cite author and source of content, must not alter or modify content, and must comply with all other terms or restrictions that may be applicable. Cover design: Piper F. Wallis Cover images: (top left) Wave-sculpted iceberg in Svalbard, Norway (Photo by Laurie M. Penland); (top right) Smithsonian Scientifi c Diving Offi cer Michael A. Lang prepares to exit from ice dive (Photo by Adam G. Marsh); (main) Kongsfjorden, Svalbard, Norway (Photo by Laurie M. Penland). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithsonian at the poles : contributions to International Polar Year science / Igor Krupnik, Michael A. Lang, and Scott E. Miller, editors. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-9788460-1-5 (pbk. -

Self-Governance in Arctic Societies: Dynamics and Trends

International Ph.D. School for Studies of Arctic Societies (IPSSAS) Self-Governance in Arctic Societies: Dynamics and Trends Proceedings of the Fourth IPSSAS Seminar Kuujjuaq, Nunavik, Canada May 22 to June 2, 2006 François Trudel (Ed.) CIÉRA (Centre interuniversitaire d’études et de recherche autochtones) Faculté des sciences sociales Université Laval, Québec, Canada The IPSSAS Steering Committee wishes to thank the following institutions and departments for various contributions to the Fourth IPSSAS Seminar in Kuujjuaq, Nunavik, Canada, in 2006: - Indian and Northern Affairs Canada / Inuit Relations Secretariat - Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada - Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada - CIÉRA (Centre interuniversitaire d’études et de recherches autochtones), Faculté des sciences sociales, Université Laval, Québec, Canada - CCI (Canadian Circumpolar Institute) and H.M. Tory Chair (Department of Anthropology), University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada - Greenland’s Home Rule, Department of Culture, Education, Research and Ecclesiastical Affairs - Ilisimatusarfik / University of Greenland - The Commission for Scientific Research in Greenland (KVUG) - Makivik Corporation - National Science Foundation of the United States of America - Alaska Native Languages Centre, University of Alaska Fairbanks - Department of Cross Cultural and Regional Studies, University of Copenhagen, Denmark - Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales (INALCO), Paris, France Cover photo: Inukshuit in the outskirts of Kuujjuaq, Nunavik. An inushuk (inukshuit in the plural form) is an arrangement of stones or cairn resembling the shape of a human. The Inuit have used inukshuit for generations for many of their activities, such as a navigational aid, a lure or a marker. Inukshuit also embody spiritual and ancestral connections and have a great symbolic meaning. -

Northern Notes

F a l l 2 0 0 2 ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. NNoorrtthheerrnn NNootteess The Newsletter of the International Arctic Social Sciences Association (IASSA) Published by the IASSA Secretariat, University of Alaska Fairbanks, PO Box 757730, Fairbanks, AK 99775-7730, USA; tel.: +1-907-474-6367; fax: +1-907-474-6370; email: [email protected]; web: www.uaf.edu/anthro/iassa; editor: Anne Sudkamp, IASSA Executive Officer, email: [email protected] In this issue Features From the President ............................................... 1 IASSA.Net ..............................................................6 From the Executive Officer ................................. 2 Call for Papers. .....................................................7 ICASS V First Announcement ............................. 2 Conferences, Meetings, and Workshops ...............8 Reports from the Arctic Council .......................... 3 Career Opportunities .............................................9 2002 Athabaskan Languages Conference ............ 5 For Students ........................................................10 Departments Bookshelf ............................................................12 About IASSA ....................................................... 5 On the Web .........................................................16 IASSA Council Members .................................... 6 From the President IASSA continues to have a strong presence as at the meeting, we changed Anne’s title from an observer at the Arctic Council (AC). IASSA -

Nunavut, a Creation Story. the Inuit Movement in Canada's Newest Territory

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE August 2019 Nunavut, A Creation Story. The Inuit Movement in Canada's Newest Territory Holly Ann Dobbins Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Dobbins, Holly Ann, "Nunavut, A Creation Story. The Inuit Movement in Canada's Newest Territory" (2019). Dissertations - ALL. 1097. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/1097 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This is a qualitative study of the 30-year land claim negotiation process (1963-1993) through which the Inuit of Nunavut transformed themselves from being a marginalized population with few recognized rights in Canada to becoming the overwhelmingly dominant voice in a territorial government, with strong rights over their own lands and waters. In this study I view this negotiation process and all of the activities that supported it as part of a larger Inuit Movement and argue that it meets the criteria for a social movement. This study bridges several social sciences disciplines, including newly emerging areas of study in social movements, conflict resolution, and Indigenous studies, and offers important lessons about the conditions for a successful mobilization for Indigenous rights in other states. In this research I examine the extent to which Inuit values and worldviews directly informed movement emergence and continuity, leadership development and, to some extent, negotiation strategies. -

Proquest Dissertations

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Role of Fur Trade Technologies in Adult Learning: A Study of Selected Inuvialuit Ancestors at Cape Krusenstern, NWT (Nunavut), Canada 1935-1947 by David Michael Button A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF EDUCATION GRADUATE DIVISION OF EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH CALGARY, ALBERTA August 2008 © David Button 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44376-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44376-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

QUN'ngiaqtiarlugu (TAKING a CLOSER LOOK) at INUIT QAUJIMAJATUQANGIT in COMMUNITY-BASED PARTICIPATORY RESEARCH by Jenny R. Rand

QUN’NGIAQTIARLUGU (TAKING A CLOSER LOOK) AT INUIT QAUJIMAJATUQANGIT IN COMMUNITY-BASED PARTICIPATORY RESEARCH by Jenny R. Rand Submitted in partial fulfillment for the requirements of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia June 2020 © Copyright by Jenny R. Rand, 2020 Dedication Past To my paternal grandparents, Eustace and Lorraine Rand, whose love for the North was part of the stories and artwork that surrounded me growing up - long before my parents ever dreamed of boarding up our home in Blomidon, Nova Scotia and moving to Kugluktuk, Nunavut. Eustace Louvain Rand (1914-1988) who traversed the Nahanni River NWT on two separate trips. The first in 1954, ran out of time and stopped short; they repeated the attempt in 1958 and made it all the way to Virginia Falls. Lorraine Geraldine (Hiltz) Rand (1917-2008) my Nanny, who traveled to Fort Smith, NWT in 1989, and who was a talented and prolific fibre artist who hooked beautiful wall hangings of northern scenes. Together, for over 30 years, my grandparents operated the general store in Port Williams, Nova Scotia. I now own my own home in Port Williams - just around the corner from their old house and from where their store sat, and it is from here that I completed this dissertation. Future For Ella, Tessa, Van, Judah, Briar, Owen and Madeline – Children, Nagligivagit, you are my future, my greatest wish for you is a brilliant and happy inuuhiq – and when you grow up - please do not forget, “You must do something to make the world more beautiful” - Miss Rumphius ii Table of Contents List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................... -

WHO ARE the INUIT? a Conversation with Qauyisaq “Kowesa” Etitiq

WHO ARE THE INUIT? A conversation with Qauyisaq “Kowesa” Etitiq Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario Elementary Teachers' Federation of Ontario (ETFO) 136 Isabella Street, Toronto, ON M4Y 0B5 416-962-3836 or 1-888-838-3836 etfo.ca ETFOprovincialoffice @ETFOeducators @ETFOeducators Copyright © July 2020 by ETFO ETFO EQUITY STATEMENT It is the goal of the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario to work with others to create schools, communities and a society free from all forms of individual and systemic discrimination. To further this goal, ETFO defines equity as fairness achieved through proactive measures which result in equality, promote diversity and foster respect and dignity for all. ETFO HUMAN RIGHTS STATEMENT The Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario is committed to: • providing an environment for members that is free from harassment and discrimination at all provincial or local Federation sponsored activities; • fostering the goodwill and trust necessary to protect the rights of all individuals within the organization; • neither tolerating nor condoning behaviour that undermines the dignity or self-esteem of individuals or the integrity of relationships; and • promoting mutual respect, understanding and co-operation as the basis of interaction among all members. Harassment and discrimination on the basis of a prohibited ground are violations of the Ontario Human Rights Code and are illegal. The Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario will not tolerate any form of harassment or discrimination, as defined by the Ontario Human Rights Code, at provincial or local Federation sponsored activities. ETFO LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT In the spirit of Truth and Reconciliation, the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario acknowledges that we are gathered today on the customary and traditional lands of the Indigenous Peoples of this territory.