William Kunstler from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search William Kunstler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tropic Times

Gift 1fihe P ; aC,Jan0 the Tropic Times Vol. 11, No. 44 Quarry Heights, Republic of Panama Dec. 4,1989 Malta summit yields hope for Soviet recovery VALLETTA, Malta (UPI) - Gorbachev made the return trip to Bush that the West would not try to Communist rule, Gorbachev arrived Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev Moscow, arriving late Sunday night, dictate the speed of change in Eastern in Malta seeking Bush's understand- emerged Sunday from his storm- the official Soviet news agency Tass Europe. ing. plagued summit with President Bush reported. With Czechoslovakia, Hungary Bush's assurances he would not go with the prize he sought - a promise Giorgi Arbatov, a longtime adviser and even East Germany moving "demonstrating on the top of the of the U.S. economic cooperation he to Gorbachev and head of Mocow's dramatically away from one-party Berlin Wall to show that we are needs to rebuild the Soviet economy. U.S.-Canada Institute think-tank, happy" visibly pleased Gorbachev. The Malta talks hold the promise was more effusive about the Also on the table was a menu of of the "political impetus that we have economic helping hand offered by three possible arms agreements: been lacking" in economic reform the United States. cutting long-range strategic efforts, Gorbachev told a joint press the United States weapons, banning the production of conference with Bush aboard the "Thechemical weapons and reducing Soviet cruise liner Maxim Gorky. the end of its economic war against conventional forces in Europe - all In his package of proposals to the Soviet Union," said Arbatov. -

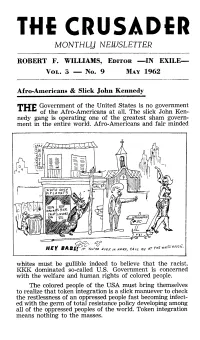

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

On the Black Panther Party

STERILIZATION-ANOTHER PARTOF THE PLAN OFBLACK GENOCIDE 10\~w- -~ ., ' ' . - _t;_--\ ~s,_~=r t . 0 . H·o~u~e. °SHI ~ TI-lE BLACK PANTI-lER, SATURDAY, MAY 8, 1971 PAGE 2 STERILIZATION-ANOTHER PART OF THE PLAN OF f;Jti~~~ oF-~dnl&r ., America's poor and minority peo- In 1964, in Mississippi a law was that u ••• • Even my maid said this should ple are the current subject for dis- passed that actually made it felony for be done. She's behind it lO0 percent." cussion in almost every state legis- anyone to become the parent of more When he (Bates) argued that one pur latur e in the country: Reagan in Cali- than one "illegitimate" child. Original- pose of the bill was to save the State fornia is reducing the alr eady subsis- ly, the bill carried a penalty stipu- money, it was pointed out that welfare tance aid given to families with children; lation that first offenders would be mothers in Tennessee are given a max O'Callaghan in Nevada has already com- sentenced to one to three years in the imum of $l5.00 a month for every child pletely cut off 3,000 poor families with State Penitentiary. Three to five years at home (Themaxim!,(,mwelfarepayment children. would be the sentence for subsequent in Tennesse, which is for a family of However, Tennessee is considering convictions. As an alternative to jail- five or more children, is $l6l.00 per dealing with "the problem" of families in~, women would have had the option of month.), and a minimum of $65.00 with "dependant children" by reducing being sterilized. -

William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe a Film by Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler

William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe A film by Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler POV www.pbs.org/pov DISCUSSION GUIDE William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe POV Letter frOm the fiLmmakers NEw YorK , 2010 Dear Colleague, William kunstler: Disturbing the Universe grew out of conver - sations that Emily and I began having about our father and his impact on our lives. It was 2005, 10 years after his death, and Hurricane Katrina had just shredded the veneer that covered racism in America. when we were growing up, our parents imbued us with a strong sense of personal responsibility. we wanted to fight injustice; we just didn’t know what path to take. I think both Emily and I were afraid of trying to live up to our father’s accomplishments. It was in a small, dusty Texas town that we found our path. In 1999, an unlawful drug sting imprisoned more than 20 percent of Tulia’s African American population. The injustice of the incar - cerations shocked us, and the fury and eloquence of family members left behind moved us beyond sympathy to action. while our father lived in front of news cameras, we found our place behind the lens. our film, Tulia, Texas: Scenes from the Filmmakers Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler. Photo courtesy of Maddy Miller Drug War helped exonerate 46 people. one day when we were driving around Tulia, hunting leads and interviews, Emily turned to me. “I think I could be happy doing this for the rest of my life,” she said, giving voice to something we had both been thinking. -

The Big Tent’ Media Report Moveon.Org

‘The Big Tent’ Media Report MoveOn.org September 12, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 3 TELEVISION ............................................................................................................................. 13 PRINT ......................................................................................................................................... 73 ONLINE…………………………………………………………………………………………89 2 MEDIA SUMMARY 3 Television CNN, America Votes 2008 The Big Tent mentioned as a blogging facility in Denver, 8/28/08. CNN, The Situation Room Mentioned the Big Tent as the place where 300 credentialed bloggers are working, 8/25/08. CNN, The Situation Room Mentioned how the Denver Nuggets’ weight room would become the Big Tent, 8/19/08. FBN, Countdown to the Closing Bell Josh Cohen interviewed about the Big Tent, 8/28/08. FBN, America’s Nightly Scorecard Mentioned Google doing a good job with the Big Tent, 8/22/08. CSPAN, Campaign 2008 Interviewed blogger Ben Tribbett about the Big Tent and filmed a walk-through of the entire tent, 8/28/08. CSPAN2, Tonight From Washington Leslie Bradshaw from New Media Strategies mentions the Big Tent during her interview, 8/26/08. MSNBC Morning Joe Interviewed several bloggers inside the Big (same clip ran on MSNBC News Live) Tent as part of Morning Joe’s “The Life of Bloggers: Cheetos-Eating, Star Wars Watching, Living in Basements?” 8/27/08. NBC; Denver, CO The Big Tent mentioned as the location of T. Boone Pickens’ event, 8/31/08. NBC; Boston, MA The Big Tent credited with helping Phillip (same clip ran in Cedar Rapids, IA; Anderson of the AlbanyProject.com and Wichita Falls, TX; New York, NY; others get work done at the convention, Cleveland, OH; Seattle, WA; interviewed Phillip Anderson and Markos San Diego, CA; Tuscon, AZ; Moulitsas about the Big Tent, 8/27/08. -

That Is the Only Hope for This Nation!

04/02/2021 NEWS AM – Happy Passover! – Day 6 The Maccabeats - Nirtzah: The Seder Finale - Passover https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9KpHb4IHYLY "Rightful liberty is unobstructed action according to our will within limits drawn around us by the equal rights of others. I do not add 'within the limits of the law,' because law is often but the tyrant's will, and always so when it violates the rights of the individual." -- Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), US Founding Father, drafted the Declaration of Independence, 3rd US President Read the Prophets & PRAY WITHOUT CEASING! That is the only hope for this nation! Please Pray that the world would WAKE UP! Time for a worldwide repentance! Remember ALL US soldiers fighting for our freedom around the world These Pray for those in our government to repent of their wicked corrupt ways. Folks Pray for TR – abnormal Mammogram having double biopsy – Positive for cancer In Pray for ZH - having trouble with PTSD Prayer- Pray for LAC – recurrent cancer getting treatment Check often Pray for Ella – emotionally disturbed abused child and brother with ? heart problem They Pray for JN – Neuro disease Change! Pray for MS – Job issues and change Pray for BB – Severe West Nile Fever –still not mobile- improving! Pray for RBH – cancer recurrence Pray for Felicia – post op problems – continuing Pray for SH and family – lady’s husband passed away and she is in Nursing home. Not doing well. Pray for MP – Very complex problems Pray that The Holy One will lead you in Your preparations for handling the world problems. -

E18-00003-1970-09-30

'21 ...· : .. : :· ... ·~; . .·. , . ....·. :.:·:1 ,•, .. church of the apocalypse pobox 9218 33604 Eye ot the Beast_ DRAFT AND RESISTANCE COUNSELLING AVAILABLE: The Pacifist Action Council (PAC) is now offering draft and resistance counselling to all interested parties as a community service. All those concerned with the preservation of life, and opposed to the killing machine, are urged to contact PAC in care of The Eye of the Beast. A new booklet titled "How to Publish a High School Underground Ne\vspaper" has just been published by two recent high school graduates in cooperation with the Cooperative Highschool Independent Press Service (CHIPS). It is an instruction manual on how to pub lish a high school underground newspaper, including editing and printing. If you'd like a copy, send a quarter if you're a high school student or group, or send two quarters if you're something else to: Al-Fadhly & Shapiro 7242 West 90th Street Los Angeles, California 90045 All money received in excess of costs will be used to publish a second edition, to be sold for less. NEW ORLEANS POLICE MURDER BLACK PANTHER: The day after Judge Baget set $100,000 bail on each of the 15 Black Panthers arrested 'in an illegal raid, another Black Panther, Kenneth Borden, was murdered and 3 comrades wounded by the New Orleans police. They were walking down a street, unarmed, when the police opened up with shotguns. The cops had fired, officials claim, only under attack. Yet no alleged weapons have been found and bystanders have denied any Panther attack was made. Police Harass Local Peace Movement Police harassment forced the Tampa Area Peace Action Coalition to move its conference scheduled for Sunday af ternoon from the Zion Lutheran Church, 2901 Highland Ave., to the University Chapel Fellowship at the Uni versity of South Florida. -

Shawyer Dissertation May 2008 Final Version

Copyright by Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: A Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967-1968 Committee: Jill Dolan, Supervisor Paul Bonin-Rodriguez Charlotte Canning Janet Davis Stacy Wolf Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: A Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967-1968 by Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2008 Acknowledgements There are many people I want to thank for their assistance throughout the process of this dissertation project. First, I would like to acknowledge the generous support and helpful advice of my committee members. My supervisor, Dr. Jill Dolan, was present in every stage of the process with thought-provoking questions, incredible patience, and unfailing encouragement. During my years at the University of Texas at Austin Dr. Charlotte Canning has continually provided exceptional mentorship and modeled a high standard of scholarly rigor and pedagogical generosity. Dr. Janet Davis and Dr. Stacy Wolf guided me through my earliest explorations of the Yippies and pushed me to consider the complex historical and theoretical intersections of my performance scholarship. I am grateful for the warm collegiality and insightful questions of Dr. Paul Bonin-Rodriguez. My committee’s wise guidance has pushed me to be a better scholar. -

William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe

WILLIAM KUNSTLER: DISTURBING THE UNIVERSE A film by Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler An 85-minute documentary film. Digital Video. Color & Black & White. Premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2009 Released theatrically by Arthouse Films in November 2009 Released on DVD on April 27, 2010 Broadcast on PBS on June 22, 2010 on the award-winning documentary series P.O.V. as the season’s opening night film. A wonderful, inspiring film. – Howard Zinn Expertly put together and never less than compelling. -The Hollywood Reporter A superior documentary. – The Los Angeles Times Shatteringly good. – The San Francisco Chronicle A fascinating portrait. – The Washington Post A magnificent profile of an irrepressible personality. – Indiewire This is a wonderful film. Emily and Sarah Kunstler have done a remarkable job. The film is great history – Alec Baldwin A sensitive truthful, insightful film. – Huffington Post A brilliant and even-handed portrait. – Hamptons.com A perfect balance of the personal and the public. - Salt Lake City Weekly A wonderful, weird, and very American story. – The Stranger A well-crafted and intimate but not uncritical tribute to both a father and a legend of the Left – The Indypendent Might just help reawaken viewers to find their own Goliaths and slingshots. - The Jewish Journal Page 2 of 15 The Film’s Title The title of the film comes from T. S. Eliot’s poem, The Love Song of Alfred J. Prufrock. At the end of his life, many of Kunstler’s speeches were entreaties to young people to have the courage take action for change. He frequently spoke about Michelangelo’s statue of David as embodying the moment when a person must choose to stand up or to fade into the crowd and lead an unexceptional life. -

A Small Slice of the Chicago Eight Trial

A Small Slice of the Chicago Eight Trial Ellen S. Podgor* The Chicago Eight trial was not the typical criminal trial, in part because it occurred at a time of society’s polarization, student demonstrations, and the rise of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Charges were levied against eight defendants, who were individuals that represented leaders in a variety of movements and groups during this time. This Essay examines the opening stages of this trial from the lens of a then relatively new criminal defense attorney, Gerald Lefcourt. It looks at his experiences before Judge Julius Hoffman and highlights how strong, steadfast criminal defense attorneys can make a difference in protecting key constitutional rights and values. Although judicial independence is crucial to a system premised on due process, it is also important that lawyers and law professors stand up to misconduct and improprieties. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 821 I. PROXIMITY AND SETTING .......................................................... 824 A. The Landscape ............................................................. 824 B. Attorney Gerald Lefcourt’s Role .................................. 828 II. ATTORNEY WITHDRAWALS AND SUBSTITUTIONS .................... 834 III. LESSONS LEARNED—RESPONDING TO MISPLACED JUDICIAL CONDUCT .............................................................................. 836 CONCLUSION ................................................................................ -

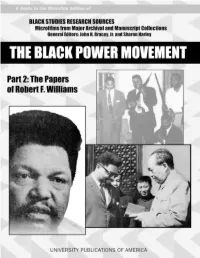

The Black Power Movement. Part 2, the Papers of Robert F

Cover: (Left) Robert F. Williams; (Upper right) from left: Edward S. “Pete” Williams, Robert F. Williams, John Herman Williams, and Dr. Albert E. Perry Jr. at an NAACP meeting in 1957, in Monroe, North Carolina; (Lower right) Mao Tse-tung presents Robert Williams with a “little red book.” All photos courtesy of John Herman Williams. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 2: The Papers of Robert F. Williams Microfilmed from the Holdings of the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor Editorial Adviser Timothy B. Tyson Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams [microform] / editorial adviser, Timothy B. Tyson ; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. 26 microfilm reels ; 35 mm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams. ISBN 1-55655-867-8 1. African Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—20th century—Sources. 3. Black nationalism— United States—History—20th century—Sources. 4. Williams, Robert Franklin, 1925— Archives. I. Title: Papers of Robert F. Williams. -

The Trial of Bobby Seale Jason Epstein

A Special Supplement The Trial of Bobby Seale Jason Epstein defendant, Bobby Seale, who is transcript will perhaps show, but in an terror. When he utters the name of I charged with first degree murder in unmistakable theatrical gift which, at defendant Rubin it is as if a chord has New Haven and is thus without bail, had an earlier time in his life, might have been struck on the Wurlitzer of a Introduction entered and left the courtroom, before been a contrivance but is now his long forgotten music hall. And when he explodes the middle initial of the The United States District Court for the judge declared a mistrial in his second nature. Though he stands only defendant Bobby G. Seale, one is made the Northern District of Illinois (East- case. On the wall behind the judge's five feet four inches tall and weighs to feel that the innocence of that ern Division) occupies several floors of bench are conventional portraits, which hardly more than the smallest of the consonant has been lost forever. the new Federal Building in Chicago's belong to the judge himself, of the formidable lady jurors, he makes use Loop. Of this thirty-story building, founding fathers, as well as one of of his diminished stature to enter the designed in steel and glass by the late Abraham Lincoln and three of peri- courtroom from a door behind his What follows is the official trans- Mies van der Rohe, the Chicago Art wigged English jurists. Above these bench so that he does not become cription, taken by the court stenogra- Institute has said, "The commitment portraits, on the upper part of the visible until he has materialized atop pher, of what the Judge read from his notes on the afternoon of November 5.