Ft] Vi 7- E Replacement Budget Funding Statement of Understanding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

On the Black Panther Party

STERILIZATION-ANOTHER PARTOF THE PLAN OFBLACK GENOCIDE 10\~w- -~ ., ' ' . - _t;_--\ ~s,_~=r t . 0 . H·o~u~e. °SHI ~ TI-lE BLACK PANTI-lER, SATURDAY, MAY 8, 1971 PAGE 2 STERILIZATION-ANOTHER PART OF THE PLAN OF f;Jti~~~ oF-~dnl&r ., America's poor and minority peo- In 1964, in Mississippi a law was that u ••• • Even my maid said this should ple are the current subject for dis- passed that actually made it felony for be done. She's behind it lO0 percent." cussion in almost every state legis- anyone to become the parent of more When he (Bates) argued that one pur latur e in the country: Reagan in Cali- than one "illegitimate" child. Original- pose of the bill was to save the State fornia is reducing the alr eady subsis- ly, the bill carried a penalty stipu- money, it was pointed out that welfare tance aid given to families with children; lation that first offenders would be mothers in Tennessee are given a max O'Callaghan in Nevada has already com- sentenced to one to three years in the imum of $l5.00 a month for every child pletely cut off 3,000 poor families with State Penitentiary. Three to five years at home (Themaxim!,(,mwelfarepayment children. would be the sentence for subsequent in Tennesse, which is for a family of However, Tennessee is considering convictions. As an alternative to jail- five or more children, is $l6l.00 per dealing with "the problem" of families in~, women would have had the option of month.), and a minimum of $65.00 with "dependant children" by reducing being sterilized. -

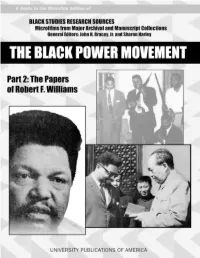

The Black Power Movement. Part 2, the Papers of Robert F

Cover: (Left) Robert F. Williams; (Upper right) from left: Edward S. “Pete” Williams, Robert F. Williams, John Herman Williams, and Dr. Albert E. Perry Jr. at an NAACP meeting in 1957, in Monroe, North Carolina; (Lower right) Mao Tse-tung presents Robert Williams with a “little red book.” All photos courtesy of John Herman Williams. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 2: The Papers of Robert F. Williams Microfilmed from the Holdings of the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor Editorial Adviser Timothy B. Tyson Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams [microform] / editorial adviser, Timothy B. Tyson ; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. 26 microfilm reels ; 35 mm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams. ISBN 1-55655-867-8 1. African Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—20th century—Sources. 3. Black nationalism— United States—History—20th century—Sources. 4. Williams, Robert Franklin, 1925— Archives. I. Title: Papers of Robert F. Williams. -

Malcolm X and Christianity

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS MALCOLM X AND CHRISTIANITY FATHIE BIN ALI ABDAT (B. Arts, Hons) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2008 Acknowledgements I extend my sincerest gratitude first to the National University of Singapore (NUS) for granting me the Masters Research Scholarship that enabled me to carry out this undertaking. Also, my thanks go out to the librarians at various universities for assisting me track down countless number of primary and secondary sources that were literally scattered around the world. Without their tireless dedication and effort, this thesis would not have been feasible. The NUS library forked out a substantial sum of money purchasing dozens of books and journals for which I am grateful for. In New York, the friendly staff at Columbia University’s Butler Library, Union Theological Seminary’s Burke Library and Schomburg Centre for Research in Black Culture provided me access to newspaper articles, FBI files, rare books and archival materials that provided much content for my work. In Malaysia, the staff at the University of Malaya enabled me to browse through Za’aba’s extensive private collection that included the journal, Moslem World & the U.S.A. In the process of writing this thesis, I am indebted to various faculty members at the Department of History such as Assoc. Prof. Ian Gordon, Assoc. Prof. Michael Feener and Assoc. Prof. Thomas Dubois, who in one way or another, helped shape my ideas on Malcolm X’s intellectual beliefs and developed my skills as an apprentice historian. -

Papers of the Naacp

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Supplement to Part 16, Board of Directors File, 1956-1965 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Supplement to Part 16, Board of Directors File, 1956-1965 Edited by John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier Project Coordinator Randolph Boehm Guide compiled by Randolph Boehm A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway * Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Papers of the NAACP. [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides. Contents: pt. 1. Meetings of the Board of Directors, records of annual conferences, major speeches, and special reports, 1909-1950 / editorial adviser, August Meier; edited by Mark Fox--pt. 2. Personal correspondence of selected NAACP officials, 1919-1939 / editorial--[etc.]--pt. 19. Youth File. 1. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People--Archives. 2. Afro-Americans--Civil Rights--History--20th century--Sources. 3. Afro- Americans--History--1877-1964--Sources. 4. United States--Race relations--Sources. I. Meier, August, 1923- . II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Title. E185.61 [Microfilm] 973'.0496073 86-892185 ISBN 1-55655-546-6 (microfilm: Supplement to pt. 16) Copyright © 1996 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. -

Randolph, A. Phillip-HQ-1

I^/.PS-OC'!'.-?.v, 12-UViU) DECLASSIFIED BY 60324 UC rBAW/DK/RYS ON 06-23-2009 Transmit the following j in \ Via TO DIRECTOR, FBI (100-149163) PROM / SAC, NEW YORK (100-23825) ApA\ SUBJECT BENJAMIN J. DAVIS, Jr. IS - C; SA »40; ISA « ^0 b2 CINAL pacifist connected w DAVIS and said then© tU) _iS2Mk^A jPHILlC-^ rnicn) the following day. 11U oa.l« BaJ . u ne naa raKen uo wirn X RUSTIN agreed to call DAVIS on Monday evening 9/8A8 h hi (II) ™ "^cause we-Je something.sol?hJn. » T*? ft,***,,* Ibo^to^uil oft He stated "weJU^e to get out of this trap we're>in> available,^ } li^^SUU^ ^\(^\y J0 /S> Bureau^ (100-149163) (RM) *HOT REOOltlSP- l^^ , U j»«* Ht - New York 100-46729 (BAYARD RUSTI^^)^®!! ^^^T ($7^ New 1 - York 100- (FELLOWSHIP OF RECONCILIATION) ,^-liY M/(7-3)2i l 1 - New York 100- (A. PHILIP^BAND6fef«>fl^5)^^ -«*><&? 1 - New York «Q.00-23825 V 'RER:mms (8) 33 3 / Exempt v:?r~ W" C^-rr*ry &L. Date of Decfcsaficaiion IndViiaate >? ,dhXJiS& &9SEP 1.7'IS 1?h- &Approved: Special Agent in Charge FD*36tRev. 12-13-56) t t F BI Date: Transmit the following in (Type in plain text or code) Via— (Priority or Method of Mailing) .!_. (U) NY 100-23825 RUSTIN said he wanted to bring DAVIS and "RANDOLPH" (probably A. PHILIP RANDOLPH) and a few others together to sit N*/ down and talk turkey "for the time has come to stop all this A^* b—— s—— • DAVIS stated that in connection with his campaign there was to be a big rally on Saturday (9/6/58) in front of the Hoter Theresa at 2:00 P.M. -

A Burkeian Analysis of the Rhetoric of Malcolm X

A BURKEIAN ANALYSIS OF THE RHETORIC OF MALCOLM X DURING THE LAST PHASE OF HIS LIFE, JUNE 1964--FEBRUARY 1965 APPROVED: AO/LLJL Chairman, Department o£ "Sceech and Drama Dean if the Graduate School Cadenhead, Evelyn, A Burkeian Analysis of the Rhetoric of Malcolm X During the Last Phase of His Life, June 1964- - February 1965. Master of Arts (Speech and Drama), May, 1972, 202 pp., bibliography, 72 titles. The purpose of the study has been to analyze the rhetoric of Malcolm X with Kenneth Burke's dramatistic pentad in order to gain a better understanding of Malcolm X's rhetorical strategies in providing answers to given situations. One speech, determined to be typical of Malcolm X during the last phase of his life, was chosen for the analysis. It was the speech delivered on December 20, 1964, during the visit of Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party candidate for the Senate. This study is divided into six chapters. Chapter I in- cludes a brief introduction to Malcolm X, the first contem- porary black revolutionary orator. It, too, establishes the justification for selecting one speech for analysis because it embodied the four philosophies Malcolm X advocated during his last year. Chapter I also introduces Kenneth Burke and his dramatistic pentad, with a separate explanation of the five terms of the pentad, act, scene, agent, agency, and purpose. A glossary of Burkeian terns to be used throughout the study concludes Chapter I. Chapter II is divided into two parts. Part I is a Burkeian scene analysis; scene being the background out of which the speech arose. -

Building a Black Bridge China’S Interaction with African-American Activists During the Cold War

Building a Black Bridge China’s Interaction with African-American Activists during the Cold War ✣ Hongshan Li On 24 December 1956, William Worthy, a special correspondent for The Baltimore Afro-American, walked across the Luohu Bridge from Hong Kong. As he set his feet down in Shenzhen, a small town in Guangdong Province, he became the first U.S. journalist to enter the People’s Republic of China (PRC) under an official invitation from the Communist regime. Following Worthy’s example, many African-American activists, including W. E. B. Du Bois, Shirley Graham Du Bois, Robert F. Williams, Mabel Williams, Vicki Garvin, Huey Newton, and Elaine Brown, traveled to and even stayed for ex- tended periods in the PRC over the next decade-and-a-half. As special guests carefully chosen by Beijing, they toured both the cities and the countryside, delivered speeches at mass rallies, and had their writings published in Chi- nese. Once back in the United States, they appeared on television and radio shows, gave public talks, and published articles in journals and newspapers, sharing their experiences in and thoughts about the PRC. With all traditional diplomatic, commercial, and cultural ties between the two countries termi- nated, the visits of these African-American activists not only allowed Beijing to maintain a controlled flow of people and information across the Pacific, but also provided it with a new instrument to engage and challenge Washington on the cultural front in the Cold War. This close interaction between the PRC and a large number of African-American activists was unprecedented in the long history of Sino-American cultural exchange. -

African-Americans in Boston : More Than 350 Years

Boston Public Library REFERENCE BANKOF BOSTON This book has been made possible through the generosity of Bank of Boston \ African-Americans in Boston More Than 350 Years Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/africanamericansOOhayd_0 African-Americans in Boston: More Than 350 Years by Robert C. Hayden Foreword by Joyce Ferriabough Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston, 1991 African-Americans in Boston: More Than 350 Years Written by Robert C. Hayden Conceived and coordinated by Joyce Ferriabough Designed by Richard Zonghi, who also coordinated production Edited by Jane Manthome Co-edited by Joyce Ferriabough, Berthe M. Gaines, C. Kelley, assisted by Frances Barna Funded in part by Bank of Boston PubUshed by Trustees of the Boston PubHc Library Typeset by Thomas Todd Company Printed by Mercantile Printing Company Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following individuals and organizations for use of the illustrations on the pages cited: T. J. Anderson (74); Associated Press Wirephoto (42 bottom, 43, 98 left, 117); Fabian Bachrach (24, 116); Bob Backoff (27 left); Banner Photo (137); Charles D. Bonner (147 left); Boston African-American Historic Site, National Park Service (38, 77, 105 right); The Boston Athenaeum (18, 35 top, 47 top, 123, 130); Boston Globe (160); Boston Housing Authority (99); Boston Red Sox (161); Boston University News Service (119 right, 133); Margaret Bumham (110); John Bynoe (26); Julian Carpenter (153); Dance Umbrella (71); Mary Frye (147 right); S. C. Fuller, Jr. (142 right); Robert Gamett (145 left); Artis Graham (86); Calvin Grimes, Jr. (84); James Guilford (83); Rev. -

Black Power Movement, Part 3: Papers of the Revolutionary Action Movement, 1962–1996

A UPA Collection from Cover: Muhammad Ahmad (Max Stanford), founder and national field chairman of RAM. Photo courtesy of Muhammad Ahmad. BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr., and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 3: Papers of the Revolutionary Action Movement, 1962–1996 Editorial Advisers Muhammad Ahmad, Ernie Allen, Jr., and John H. Bracey, Jr. Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A UPA Collection from 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 3, Papers of the Revolutionary Action Movement, 1962–1996 [microform] / editorial advisers, Muhammad Ahmad, Ernie Allen, and John H. Bracey; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. microfilm reels.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. Part 3, Papers of the Revolutionary Action Movement, 1962–1996. Summary: Reproduces the writings and correspondence of Muhammad Ahmad (Max Stanford); RAM internal documents; records on allied organizations, including African Peoples Party, Black Liberation Army, Black Panther Party, Black United Front, Black Workers Congress, Institute of Black Studies, League of Revolutionary Black Workers, Republic of New Africa, and Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee; rare serial publications, including Black America, Soulbook, Unity and Struggle, Black Vanguard, Crossroads, and Jihad News; and, government documents such as the FBI file on Max Stanford, testimony about RAM’s role in the urban rebellions, and subject files covering key leaders associated with RAM including Malcolm X, Robert F. -

Seeing Shadows: FBI Surveillance, Gender, and Black Women Activists Kiara Sample Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses Undergraduate Research Spring 2018 Seeing Shadows: FBI Surveillance, Gender, and Black Women Activists Kiara Sample Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/undergrad_etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Sample, Kiara, "Seeing Shadows: FBI Surveillance, Gender, and Black Women Activists" (2018). Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses. 7. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/undergrad_etd/7 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Seeing Shadows: FBI Surveillance, Gender, and Black Women Activists Kiara Sample April 7, 2018 Washington University in St. Louis 2 INTRODUCTION On the morning of May 14, 1958 two New York City Police detectives, Joseph Kiernan and Michael Bonura,1 knocked on the door of 25-46 99th Street, the duplex of Betty Shabazz and Malcom X in Queens, New York.2 Yvonne X Molette lived on the ground floor of the duplex with her sister, Audrey X Rice, her younger 13-year old sister, and her husband John X Molette. Yvonne Molette answered the door when the detectives requested a “Mrs. Margaret Dorsey,” and when Yvonne Molette told them a Margaret Dorsey did not reside in the duplex, the agents asked to come into the home and look around. -

Randolph, A. Phillip-HQ-2

EXIHPTED FB.OH AUTOllATIC D 1 C L AS S I F I CAT I OM. AUTHORITY I:'ERI¥SD FEOH: ( ft. t FBI AUTOimilC DECLASSIFICATION GUIDE EXIHPTIOII CODE ZSXH^ G) DATS 06-20-Z009 cosrb: tJMARY JIain File No: 100-55616 Date: January 12, 1965 See also: 61-5 (Section 8 serial 43) Subject: A. Philip Randolph Date Searched: 3/19/64 All logical variations of subject *s name and aliases were searched and identical references were found as: Philip Randolph Philip^R^Qlph lA. Phillip^^^ll E. Phillip®E[^Alph ALL US. Ia. Philii^l^iidolf INFCFJ.1ATI0N CONTAIKEl) E. Phillip^^dolph A. Randolph HEREIil IS UNCLASSIFIED. I EXCBPI "" J, [A.P. RandQl^ WHERE SHOWN ' ThJMil^^ A. Paul<3^Bi)lph 5THERWISE.- Phiic^l^dolph ' ' A. Phil'SRindol r<£\ \l Philij/SRandoltolL-. A, Philipp^^p^olph ^/V / M>hilip A.igsSi^ph "A. Philip^SRaSdolph Philipp^^ji^lph ^HSSdolph A. PhillipS>Rag4oiph Philips " A. Phillips^^gdQlgli Phill^OToT A.F. Phi llip -Pl^armo Iph Phillip®I«iS4o!lpJh ,Asa P.®RaMolph Phillip A^aS^olph Asa Philijy^andolph Phillip^^S^^o Iph , I Phillip^ndolph Ph-ippil®ffafedolph I |Asa I lAsa Phillips®Randolph Also searched as P. Randolph. See page 189 in summary. This is a summary of information obtained from a review of all "see" references to the subject in Bureau files under the names and aliases listed above. All references under the above names containing data identical mth. the subject have been included except any indicated at the end of this suiimiary under the heading REFERENCES NOT DICmDBD IS IHIS SXBBIARY.