WALTER CRONKITE – IMAGE #7 the 1968 Democratic National

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Additional Document

-“Both Spectacular and Unremarkable” Letter of Allegation regarding the Excessive Use of Force and Discrimination by the Philadelphia Police Department in response to Black Lives Matter protests in May and June of 2020 Prepared and submitted by the Andy and Gwen Stern Community Lawyering Clinic of the Drexel University Thomas R. Kline School of Law and the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania as a Joint Submission to the UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions. Much of the credit for this submission belongs to the volunteers who spent countless hours investigating and documenting the events recounted here, as well as interviewing witnesses and victims, editing, and repeatedly verifying the accuracy of this submission. We thank Cal Barnett-Mayotte, Jeremy Gradwohl, Connor Hayes, Tue Ho, Bren Jeffries, Ryan Nasino, Juan Palacio Moreno, Lena Popkin, Katie Princivalle, Caitlin Rooney, Abbie Starker, Ceara Thacker, and William Walker. Cc: Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance Special Rapporteur on Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The tragic killings of George Floyd in Minneapolis and Breonna Taylor in Louisville, and the ongoing and disproportionate killings of Black and Brown people by law enforcement throughout the United States, have sparked demonstrations against police brutality and racism in all fifty states – and around the world. Given Philadelphia’s own history of racially discriminatory policing, it was expected and appropriate that such protests would happen here as well. -

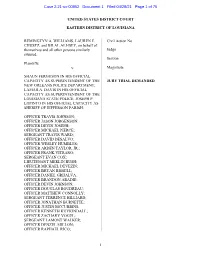

Case 2:21-Cv-00852 Document 1 Filed 04/28/21 Page 1 of 75

Case 2:21-cv-00852 Document 1 Filed 04/28/21 Page 1 of 75 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA REMINGTYN A. WILLIAMS, LAUREN E. Civil Action No. CHUSTZ, and BILAL ALI-BEY, on behalf of themselves and all other persons similarly Judge situated, Section Plaintiffs v. Magistrate SHAUN FERGUSON IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS SUPERINTENDENT OF THE JURY TRIAL DEMANDED NEW ORLEANS POLICE DEPARTMENT; LAMAR A. DAVIS IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS SUPERINTENDENT OF THE LOUISIANA STATE POLICE; JOSEPH P. LOPINTO IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS SHERIFF OF JEFFERSON PARISH; OFFICER TRAVIS JOHNSON; OFFICER JASON JORGENSON; OFFICER DEVIN JOSEPH; OFFICER MICHAEL PIERCE; SERGEANT TRAVIS WARD; OFFICER DAVID DESALVO; OFFICER WESLEY HUMBLES; OFFICER ARDEN TAYLOR, JR.; OFFICER FRANK VITRANO; SERGEANT EVAN COX; LIEUTENANT MERLIN BUSH; OFFICER MICHAEL DEVEZIN; OFFICER BRYAN BISSELL; OFFICER DANIEL GRIJALVA; OFFICER BRANDON ABADIE; OFFICER DEVIN JOHNSON; OFFICER DOUGLAS BOUDREAU; OFFICER MATTHEW CONNOLLY; SERGEANT TERRENCE HILLIARD; OFFICER JONATHAN BURNETTE; OFFICER JUSTIN MCCUBBINS; OFFICER KENNETH KUYKINDALL; OFFICER ZACHARY VOGEL; SERGEANT LAMONT WALKER; OFFICER DENZEL MILLON; OFFICER RAPHAEL RICO; 1 Case 2:21-cv-00852 Document 1 Filed 04/28/21 Page 2 of 75 OFFICER JAMAL KENDRICK; SERGEANT DANIEL HIATT; OFFICER JEFFREY CROUCH; OFFICER JOHN CABRAL; OFFICER MATTHEW EZELL; OFFICER JAMES CUNNINGHAM; OFFICER DEMOND DAVIS; OFFICER JOSHUA DIAZ; SERGEANT STEPHEN NGUYEN; OFFICER VINH NGUYEN; OFFICER MATTHEW MCKOAN; CAPTAIN BRIAN LAMPARD; CAPTAIN LEJON ROBERTS; DEPUTY CHIEF JOHN THOMAS; JOHN DOES 1-100; JOHN POES 1-50; JOHN ROES 1-50, Defendants 2 Case 2:21-cv-00852 Document 1 Filed 04/28/21 Page 3 of 75 CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT INTRODUCTION 1. -

Chicago 7’ by Joshua Furst

YOUR SHABBAT EDITION • OCTOBER 23, 2020 Stories for you to savor over Shabbat and through the weekend, in printable format. Sign up at forward.com/shabbat. GET THE LATEST AT FORWARD.COM 1 GET THE LATEST AT FORWARD.COM Culture Aaron Sorkin’s moralizing liberal fantasy betrays the real ‘Chicago 7’ By Joshua Furst According to the lore provided to the press, the the United States stood firmly against radical agitation development of Aaron Sorkin’s new movie, “The Trial of of all stripes. the Chicago 7,” originated in 2007 when Steven It was a show trial in the classic sense, political theater Spielberg, who at the time was toying with making the meant to affirm the government’s power. That it failed film himself, summoned Sorkin to his home and urged in this goal owes largely to the chaotic drama that him to write the screenplay for him. Interestingly, transpired within the courtroom with, on the one side, Sorkin had never heard of the trial, but to a certain kind Judge Julius Hoffman, an overbearing authoritarian of educated liberal possessing a working knowledge of presence incapable of hiding his prejudice, and on the its historic importance — and this, one must assume, other, defendants who used the trial as another stage includes Spielberg — a courtroom battle of ideas with from which to project their various political messages. nothing less at stake than the soul of America must If the government’s purpose was to put the have seemed to be a perfect match for his very specific counterculture on trial, the defendants used their wit talents. -

Technological Surveillance and the Spatial Struggle of Black Lives Matter Protests

No Privacy, No Peace? Technological Surveillance and the Spatial Struggle of Black Lives Matter Protests Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Eyako Heh The Ohio State University April 2021 Project Advisor: Professor Joel Wainwright, Department of Geography I Abstract This paper investigates the relationship between technological surveillance and the production of space. In particular, I focus on the surveillance tools and techniques deployed at Black Lives Matter protests and argue that their implementation engenders uneven outcomes concerning mobility, space, and power. To illustrate, I investigate three specific forms and formats of technological surveillance: cell-site simulators, aerial surveillance technology, and social media monitoring tools. These tools and techniques allow police forces to transcend the spatial-temporal bounds of protests, facilitating the arrests and subsequent punishment of targeted dissidents before, during, and after physical demonstrations. Moreover, I argue that their unequal use exacerbates the social precarity experienced by the participants of demonstrations as well as the racial criminalization inherent in the policing of majority Black and Brown gatherings. Through these technological mediums, law enforcement agents are able to shape the physical and ideological dimensions of Black Lives Matter protests. I rely on interdisciplinary scholarly inquiry and the on- the-ground experiences of Black Lives Matter protestors in order to support these claims. In aggregate, I refer to this geographic phenomenon as the spatial struggle of protests. II Acknowledgements I extend my sincerest gratitude to my advisor and former professor, Joel Wainwright. Without your guidance and critical feedback, this thesis would not have been possible. -

Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed to Police Its Police

DePaul Journal for Social Justice Volume 10 Issue 1 Winter 2017 Article 2 February 2017 Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed To Police Its Police Elizabeth J. Andonova Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jsj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legislation Commons, Public Law and Legal Theory Commons, and the Social Welfare Law Commons Recommended Citation Elizabeth J. Andonova, Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed To Police Its Police, 10 DePaul J. for Soc. Just. (2017) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jsj/vol10/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal for Social Justice by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andonova: Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed To Police I Author: Elizabeth J. Andonova Source: The National Lawyers Guild Source Citation: 73 LAW. GUILD REV. 2 (2016) Title: Cycle of Misconduct: How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed to Police the Police Republication Notice This article is being republished with the express consent of The National Lawyers Guild. This article was originally published in the National Lawyers Guild Summer 2016 Review, Volume 73, Number 2. That document can be found at: https://www.nlg.org/nlg-review/wp- content/uploads/sites/2/2016/11/NLGRev-73-2-final-digital.pdf. The DePaul Journal for Social Justice would like to thank the NLG for granting us the permission to republish this article. -

Community, Identity, and Spatial Politics in San Francisco Public Housing, 1938--2000

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2005 "More than shelter": Community, identity, and spatial politics in San Francisco public housing, 1938--2000 Amy L. Howard College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Public Policy Commons, United States History Commons, Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Howard, Amy L., ""More than shelter": Community, identity, and spatial politics in San Francisco public housing, 1938--2000" (2005). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623466. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-7ze6-hz66 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. Furtherowner. reproduction Further reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. “MORE THAN SHELTER”: Community, Identity, and Spatial Politics in San Francisco Public Housing, 1938-2000 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Amy Lynne Howard 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

SVDH Annlrept05.3

BUILDING THE FUTURE ONE FAMILY AT A TIME Annual Report 2004 – 2005 Saint Vincent’s Day Home Serving God’s people...with the full measure of one’s life Sister Ann Maureen Celebrates aureen Murphy attended Holy Family Day Home as a child, but didn’t like it much and Her Golden wanted to stay home. She didn’t have that option because her mother worked, and M drove a car—somewhat scandalous in those times—so off she went. Jubilee She returned in her high school years as a volunteer. It was then that she began to appreciate the Day Home for the work it did for children and families. This experience also allowed her to see the human side of the Sisters—real people who competed in jacks tournaments and played Recollections from a Friend basketball with the children. I have known Maureen (Sister Ann Teacher, Nurse, Housewife, Nun? Maureen) since we were high-school For Sister Ann Maureen’s generation, women’s choices were generally pretty classmates at Immaculate Conception limited, and none of them were immediately compelling. Part of her fought the Academy in San Francisco. idea of the convent, but it was the other side of her that won out. And once she While Maureen was one of the knew, there was never a question of which A Passion for more quiet members of our circle, she order she would choose. Social Justice was also humorous and fun-loving. Sister Ann And she could be a bit of a rebel. I Doing the Work Others Don’t Do Maureen recall one Lenten Season when the The Sisters of the Holy Family are known combines her Sisters told us to remove the photos as the “gleaners,” those who go into the commitment of movie stars we had taped up in our fields after they have been harvested, to social justice lockers. -

People's Electric: Engaged Legal Education at Rutgers-Newark

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 40 Number 1 The Law: Business of Profession? The Continuing Relevance of Julius Henry Article 3 Cohen for the Practice of Law in the Twenty- First Century 2021 People’s Electric: Engaged Legal Education at Rutgers-Newark Law School in the 1960s and 1970s George W. Conk Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal Education Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation George W. Conk, People’s Electric: Engaged Legal Education at Rutgers-Newark Law School in the 1960s and 1970s, 40 Fordham Urb. L.J. 503 (2012). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol40/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONK_CHRISTENSEN (DO NOT DELETE) 4/15/2013 5:50 PM PEOPLE’S ELECTRIC: ENGAGED LEGAL EDUCATION AT RUTGERS-NEWARK LAW SCHOOL IN THE 1960S AND 1970S George W. Conk* Why Newark? .......................................................................................... 503 Impact Litigation ................................................................................... 506 In Tune with the Times ........................................................................ -

Pop Dreams Music, Movies, and the Media in the American 1960S 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

POP DREAMS MUSIC, MOVIES, AND THE MEDIA IN THE AMERICAN 1960S 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Archie Loss | 9780155041462 | | | | | Pop Dreams Music, Movies, and the Media in the American 1960s 1st edition PDF Book Reference Reviews. Archived from the original on May 11, Their manager Brian Epstein encouraged the group to wear suits. More than people cheered slogans such as "Give us back our hair! Years :. Archived from the original on April 29, Retrieved May 23, History of the Flying Disc. Kennedy , a Keynesian [8] and staunch anti-communist , pushed for social reforms. Joan Baez and Bob Dylan , 28 August Within and across many disciplines, many other creative artists, authors, and thinkers helped define the counterculture movement. In Britain, the Labour Party gained power in Chicago Tribune. Pope Paul VI. Chicago Seven. King Saud. Thompson — journalist, author Kurt Vonnegut — author, pacifist, humanist Andy Warhol — artist Leonard Weinglass — attorney Alan Watts — philosopher Neil Young born musician, activist. Paul Newman , Free jazz is strongly associated with the s innovations of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor and the later works of saxophonist John Coltrane. Not all of them were considered hippies and protesters. Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original PDF on 13 July He travelled widely and his work was often discussed in the mass media, becoming one of the few American intellectuals to gain such attention. Be on the lookout for your Britannica newsletter to get trusted stories delivered right to your inbox. The declaration "all men are created equal See also: Counterculture of the s and Timeline of s counterculture. Well, a Surrealist would, anyway. -

William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe a Film by Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler

William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe A film by Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler POV www.pbs.org/pov DISCUSSION GUIDE William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe POV Letter frOm the fiLmmakers NEw YorK , 2010 Dear Colleague, William kunstler: Disturbing the Universe grew out of conver - sations that Emily and I began having about our father and his impact on our lives. It was 2005, 10 years after his death, and Hurricane Katrina had just shredded the veneer that covered racism in America. when we were growing up, our parents imbued us with a strong sense of personal responsibility. we wanted to fight injustice; we just didn’t know what path to take. I think both Emily and I were afraid of trying to live up to our father’s accomplishments. It was in a small, dusty Texas town that we found our path. In 1999, an unlawful drug sting imprisoned more than 20 percent of Tulia’s African American population. The injustice of the incar - cerations shocked us, and the fury and eloquence of family members left behind moved us beyond sympathy to action. while our father lived in front of news cameras, we found our place behind the lens. our film, Tulia, Texas: Scenes from the Filmmakers Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler. Photo courtesy of Maddy Miller Drug War helped exonerate 46 people. one day when we were driving around Tulia, hunting leads and interviews, Emily turned to me. “I think I could be happy doing this for the rest of my life,” she said, giving voice to something we had both been thinking. -

Murals & Portraits

RICHARD AVEDON Murals & Portraits May 4 – July 6, 2012 B C A D Galleries: A) Andy Warhol and members of The Factory B) The Chicago Seven C) The Mission Council D) Allen Ginsberg’s family Murals: A) Andy Warhol and members of The Factory: Paul Morrissey, director; Joe Dallesandro, actor; Candy Darling, actor; Eric Emerson, actor; Jay Johnson, actor; Tom Hompertz, actor; Gerard Malanga, poet; Viva, actress; Paul Morrissey; Taylor Mead, actor; Brigid Polk, actress; Joe Dallesandro; Andy Warhol, artist, New York, October 30, 1969, printed 1975 Silver gelatin prints, three panels mounted on linen 123 x 374 1/2 inches (312.4 x 951.2 cm) AP 1/2, edition of 2 B) The Chicago Seven: Lee Weiner, John Froines, Abbie Hoffman, Rennie Davis, Jerry Rubin, Tom Hayden, Dave Dellinger, Chicago, Illinois, November 5, 1969, printed 1969 Silver gelatin prints, three panels mounted on linen 121 3/4 x 242 3/4 inches (309.2 x 616.6 cm) Edition 2/2 + 1 AP C) The Mission Council: Hawthorne Q. Mills, Mission Coordinator; Ernest J. Colantonio, Counselor of Embassy for Administrative Affairs; Edward J. Nickel, Minister Counselor for Public Affairs; John E. McGowan, Minister Counselor for Press Affairs; George D. Jacobson, Assistant Chief of Staff, Civil Operations and Rural Development Support; General Creighton W. Abrams, Jr., Commander, United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam; Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker; Deputy Ambassador Samuel D. Berger; John R. Mossler, Minister and Director, United States Agency for International Development; Charles A. Cooper, Minister