Iraq's Minorities and Other Vulnerable Groups: Legal Framework, Documentation and Human Rights May 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mandaeans

The Mandaeans A Story of Survival in the Modern World PHOTO: DAVID MAURICE SMITH / OCULI refugees and spoken to immigration officials in Aus- The Mandaeans appear to be one of the most tralian embassies and international NGOs about their misunderstood and vulnerable groups. Apart from being desperate plight. She laments that the conditions in a small community, even fewer than Yazidis, they do which they live are far worse than she could have ever not belong to a large religious organisation or have imagined, and she fears they may have been forgotten links with powerful tribes that can protect them, so by the international community overwhelmed by the their vulnerability makes them an easy target. To make massive displacement and the humanitarian disaster matters worse they are scattered all over the country, caused by the Syrian civil war. so they are the only minority group in Iraq without a There is no doubt that more of a decade of sectarian safe enclave. If the violence persists, it is feared their infighting has had a devastating impact on Iraqi society ancient culture and religion will be lost forever. as a whole. But religious minority groups have borne the brunt of the violence. For the past 14 years Mand- andaeans have a long history of per- aeans, like many other minorities, have been subjected secution. Their survival into the modern to persecution, murder, kidnappings, displacement, world is little short of a miracle. Their forced conversion to Islam, forced marriage, cruel M origins can be traced to the Jordan treatment, confiscation of assets including property and Valley area and it is thought that they may have migrated the destruction of their cultural and religious heritage. -

Turkey and Iraq: the Perils (And Prospects) of Proximity

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT I RAQ AND I TS N EIGHBORS Iraq’s neighbors are playing a major role—both positive and negative—in the stabilization and reconstruction of “the new Iraq.” As part of the Institute’s “Iraq and Henri J. Barkey Its Neighbors” project, a group of leading specialists on the geopolitics of the region and on the domestic politics of the individual countries is assessing the interests and influence of the countries surrounding Iraq. In addition, these specialists are examining how Turkey and Iraq the situation in Iraq is impacting U.S. bilateral relations with these countries. Henri Barkey’s report on Turkey is the first in a series of USIP special reports on “Iraq The Perils (and Prospects) of Proximity and Its Neighbors” to be published over the next few months. Next in the series will be a study on Iran by Geoffrey Kemp of the Nixon Center. The “Iraq and Its Neighbors” project is directed by Scott Lasensky of the Institute’s Research and Studies Program. For an overview of the topic, see Phebe Marr and Scott Lasensky, “An Opening at Sharm el-Sheikh,” Beirut Daily Star, November 20, 2004. Henri J. Barkey is the Bernard L. and Bertha F. Cohen Professor of international relations at Lehigh University. He served as a member of the U.S. State Department Policy Planning Staff (1998–2000), working primarily on issues related to the Middle East, the eastern Mediterranean, and intelligence matters. -

Kuzey Suriye'deki Türkmen Yerleşimlerinin Çağdaş

AŞT I AR IRM AS A Y LA N R Ü I D 2019 / K EYLÜL - EKİM T ABDULHALİK BAKIR - SÜLEYMAN PEKİN R D Ü CİLT: 123 SAYI: 242 A T KUZEY SURİYE’DEKİ TÜRKMEN YERLEŞİMLERİ SAYFA: 89-130 Türk Dünyası Araştırmaları Eylül - Ekim 2019 TDA Cilt: 123 Sayı: 242 Sayfa: 89-130 Makale Türü: Araştırma Geliş Tarihi: 15.07.2019 Kabul Tarihi: 16.09.2019 KUZEY SURİYE’DEKİ TÜRKMEN YERLEŞİMLERİNİN ÇAĞDAŞ TARİHİ VE STRATEJİK ALTYAPISI ÜZERİNE GENEL BİR DEĞERLENDİRME Prof. Dr. Abdulhalik BAKIR* - Süleyman PEKİN** Öz ‘Coğrafya kaderdir’ deniyor ve bu kader Ortadoğu’da sınırlarla birlikte sık sık değişiyor. 2011 yılından buna dahil olan Suriye’nin özellikle Kuzey kıs- mındaki dil, mezhep ve etnik çeşitlilik Küresel ve Bölgesel Güçlerin rekabetine payanda olmuş durumda. Suriye Devleti’nin resmî idarî yapısındaki 14 vilaye- tin Kuzey Suriye’yi oluşturan 5’inde (Halep, Haseki, Rakka, İdlip ve Lazkiye) bu güçlerin ve buna bağlı olarak farklı grupların mücadeleleri sürmektedir. Bu gruplardan biri ve tarihî açıdan en köklü olanlardan Türkmenlerin bölge üze- rinde yaygın bir yerleşimi söz konusudur. Modern zaman olarak son yüzyıllık periyot içerisinde Millî Mücadele ve Manda, Bağımsızlık ve Baas (Esadlar), İç Savaş ve Tükmenler dönemleriyle Kuzey Suriye’deki Türkmen yerleşim yerlerinin çağdaş tarihini bu makalede ana hatlarıyla incelemeye çalıştık. Yine aynı şekilde Türkmen yerleşimlerinin stratejik alt yapısını da Nüfus ve Nüfuz Etkinlikleri ile Toplumsal Arkaplan çer- çevesinde ele alarak genel bir değerlendirmede bulunduk. Sonuç olarak hem Kuzey Suriye’nin hem de Türkmenlerin Türkiye için önemi artarak sürmektedir. Anahtar kelimeler: Türkmen, Kuzey Suriye, İç Savaş, Esad, Sınırlar, Kimlik, Federasyon. A General Evaluation On The Contemporary History And Strategic Infrastructure Of Turkmen Settlements In North Syria Abstract It is called ‘geography is destiny’ and this fate changes frequently with the borders in the Middle East. -

Turkmen of Iraq

Turkmen of Iraq By Mofak Salman Kerkuklu 1 Mofak Salman Kerkuklu Turkmen of Iraq Dublin –Ireland- 2007 2 The Author Mofak Salman Kerkuklu graduated in England with a BSc Honours in Electrical and Electronic Engineering from Oxford Brookes University and completed MSc’s in both Medical Electronic and Physics at London University and a MSc in Computing Science and Information Technology at South Bank University. He is also a qualified Charter Engineer from the Institution of Engineers of Ireland. Mr. Mofak Salman is an author of a book “ Brief History of Iraqi Turkmen”. He is the Turkmeneli Party representative for both Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom. He has written a large number of articles that were published in various newspapers. 3 Purpose and Scope This book was written with two clear objectives. Firstly, to make an assessment of the current position of Turkmen in Iraq, and secondly, to draw the world’s attention to the situation of the Turkmen. This book would not have been written without the support of Turkmen all over the world. I wish to reveal to the world the political situation and suffering of the Iraqi Turkmen under the Iraqi regime, and to expose Iraqi Kurdish bandits and reveal their premeditated plan to change the demography of the Turkmen-populated area. I would like to dedicate this book to every Turkmen who has been detained in Iraqi prisons; to Turkmen who died under torture in Iraqi prisons; to all Turkmen whose sons and daughters were executed by the Iraqi regime; to all Turkmen who fought and died without seeing a free Turkmen homeland; and to the Turkmen City of Kerkuk, which is a bastion of cultural and political life for the Turkmen resisting the Kurdish occupation. -

Looking Into Iraq

Chaillot Paper July 2005 n°79 Looking into Iraq Martin van Bruinessen, Jean-François Daguzan, Andrzej Kapiszewski, Walter Posch and Álvaro de Vasconcelos Edited by Walter Posch cc79-cover.qxp 28/07/2005 15:27 Page 2 Chaillot Paper Chaillot n° 79 In January 2002 the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) beca- Looking into Iraq me an autonomous Paris-based agency of the European Union. Following an EU Council Joint Action of 20 July 2001, it is now an integral part of the new structures that will support the further development of the CFSP/ESDP. The Institute’s core mission is to provide analyses and recommendations that can be of use and relevance to the formulation of the European security and defence policy. In carrying out that mission, it also acts as an interface between European experts and decision-makers at all levels. Chaillot Papers are monographs on topical questions written either by a member of the ISS research team or by outside authors chosen and commissioned by the Institute. Early drafts are normally discussed at a semi- nar or study group of experts convened by the Institute and publication indicates that the paper is considered Edited by Walter Posch Edited by Walter by the ISS as a useful and authoritative contribution to the debate on CFSP/ESDP. Responsibility for the views expressed in them lies exclusively with authors. Chaillot Papers are also accessible via the Institute’s Website: www.iss-eu.org cc79-Text.qxp 28/07/2005 15:36 Page 1 Chaillot Paper July 2005 n°79 Looking into Iraq Martin van Bruinessen, Jean-François Daguzan, Andrzej Kapiszewski, Walter Posch and Álvaro de Vasconcelos Edited by Walter Posch Institute for Security Studies European Union Paris cc79-Text.qxp 28/07/2005 15:36 Page 2 Institute for Security Studies European Union 43 avenue du Président Wilson 75775 Paris cedex 16 tel.: +33 (0)1 56 89 19 30 fax: +33 (0)1 56 89 19 31 e-mail: [email protected] www.iss-eu.org Director: Nicole Gnesotto © EU Institute for Security Studies 2005. -

Report Iraq: Travel Documents and Other Identity Documents

l Report Iraq: Travel documents and other identity documents Report Iraq: Travel documents and other identity documents LANDINFO –16DECEMBER 2015 1 About Landinfo’s reports The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The information is researched and evaluated in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes, but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of origin information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. © Landinfo 2016 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. -

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya About MERI The Middle East Research Institute engages in policy issues contributing to the process of state building and democratisation in the Middle East. Through independent analysis and policy debates, our research aims to promote and develop good governance, human rights, rule of law and social and economic prosperity in the region. It was established in 2014 as an independent, not-for-profit organisation based in Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Middle East Research Institute 1186 Dream City Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq T: +964 (0)662649690 E: [email protected] www.meri-k.org NGO registration number. K843 © Middle East Research Institute, 2017 The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of MERI, the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publisher. The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict MERI Policy Paper Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya October 2017 1 Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................4 2. “Reconciliation” after genocide .........................................................................................................5 -

Country of Origin Information Iraq

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION IRAQ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) October 2005 This report has been produced by UNHCR on the basis of information obtained from a variety of publicly available sources, analyses and comments. The purpose of the report is to serve as a reference for a breadth of country of origin information and thereby assists, inter alia, in the asylum determination process and when assessing the feasibility of returns to Iraq in safety and dignity. The information contained does not purport to be exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, and incomplete, inaccurate or incorrect information cannot be ruled out. The inclusion of information in this report does not constitute an endorsement of the information or views of third parties. Neither does such information necessarily represent statements of policy or views of UNHCR or the United Nations. In particular the use of ethnic-sectarian terms such as ‘Shiite’, ‘Sunni’ or ‘Kurd’ does not constitute an endorsement of sectarianism but merely reflects the current realities on the ground (i.e. these groups should not be considered homogenous entities). ii Table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................ III LIST OF ACRONYMS ..................................................................................................VII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 1 A. INTRODUCTION -

Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region

KURDISTAN RISING? CONSIDERATIONS FOR KURDS, THEIR NEIGHBORS, AND THE REGION Michael Rubin AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region Michael Rubin June 2016 American Enterprise Institute © 2016 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any man- ner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. American Enterprise Institute 1150 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 www.aei.org. Cover image: Grand Millennium Sualimani Hotel in Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan, by Diyar Muhammed, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons. Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Who Are the Kurds? 5 2. Is This Kurdistan’s Moment? 19 3. What Do the Kurds Want? 27 4. What Form of Government Will Kurdistan Embrace? 56 5. Would Kurdistan Have a Viable Economy? 64 6. Would Kurdistan Be a State of Law? 91 7. What Services Would Kurdistan Provide Its Citizens? 101 8. Could Kurdistan Defend Itself Militarily and Diplomatically? 107 9. Does the United States Have a Coherent Kurdistan Policy? 119 Notes 125 Acknowledgments 137 About the Author 139 iii Executive Summary wo decades ago, most US officials would have been hard-pressed Tto place Kurdistan on a map, let alone consider Kurds as allies. Today, Kurds have largely won over Washington. -

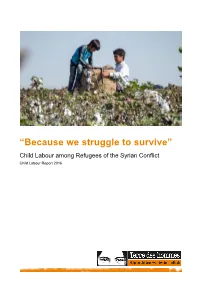

'Because We Struggle to Survive'

“Because we struggle to survive” Child Labour among Refugees of the Syrian Conflict Child Labour Report 2016 Disclaimer terre des hommes Siège | Hauptsitz | Sede | Headquarters Avenue de Montchoisi 15, CH-1006 Lausanne T +41 58 611 06 66, F +41 58 611 06 77 E-mail : [email protected], CCP : 10-11504-8 Research support: Ornella Barros, Dr. Beate Scherrer, Angela Großmann Authors: Barbara Küppers, Antje Ruhmann Photos : Front cover, S. 13, 37: Servet Dilber S. 3, 8, 12, 21, 22, 24, 27, 47: Ollivier Girard S. 3: Terre des Hommes International Federation S. 3: Christel Kovermann S. 5, 15: Terre des Hommes Netherlands S. 7: Helmut Steinkeller S. 10, 30, 38, 40: Kerem Yucel S. 33: Terre des hommes Italy The study at hand is part of a series published by terre des hommes Germany annually on 12 June, the World Day against Child Labour. We would like to thank terre des hommes Germany for their excellent work, as well as Terre des hommes Italy and Terre des Hommes Netherlands for their contributions to the study. We would also like to thank our employees, especially in the Middle East and in Europe for their contributions to the study itself, as well as to the work of editing and translating it. Terre des hommes (Lausanne) is a member of the Terre des Hommes International Federation (TDHIF) that brings together partner organisations in Switzerland and in other countries. TDHIF repesents its members at an international and European level. First published by terre des hommes Germany in English and German, June 2016. -

The Case of the Iraqi Disputed Territories Declaration Submitted By

Title: Education as an Ethnic Defence Strategy: The Case of the Iraqi Disputed Territories Declaration Submitted by Kelsey Jayne Shanks to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics, October 2013. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Kelsey Shanks ................................................................................. 1 Abstract The oil-rich northern districts of Iraq were long considered a reflection of the country with a diversity of ethnic and religious groups; Arabs, Turkmen, Kurds, Assyrians, and Yezidi, living together and portraying Iraq’s demographic makeup. However, the Ba’ath party’s brutal policy of Arabisation in the twentieth century created a false demographic and instigated the escalation of identity politics. Consequently, the region is currently highly contested with the disputed territories consisting of 15 districts stretching across four northern governorates and curving from the Syrian to Iranian borders. The official contest over the regions administration has resulted in a tug-of-war between Baghdad and Erbil that has frequently stalled the Iraqi political system. Subsequently, across the region, minority groups have been pulled into a clash over demographic composition as each disputed districts faces ethnically defined claims. The ethnic basis to territorial claims has amplified the discourse over linguistic presence, cultural representation and minority rights; and the insecure environment, in which sectarian based attacks are frequent, has elevated debates over territorial representation to the height of ethnic survival issues. -

Poverty Rates

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Mapping Poverty inIraq Mapping Poverty Where are Iraq’s Poor: Poor: Iraq’s are Where Acknowledgements This work was led by Tara Vishwanath (Lead Economist, GPVDR) with a core team comprising Dhiraj Sharma (ETC, GPVDR), Nandini Krishnan (Senior Economist, GPVDR), and Brian Blankespoor (Environment Specialist, DECCT). We are grateful to Dr. Mehdi Al-Alak (Chair of the Poverty Reduction Strategy High Committee and Deputy Minister of Planning), Ms. Najla Ali Murad (Executive General Manager of the Poverty Reduction Strategy), Mr. Serwan Mohamed (Director, KRSO), and Mr. Qusay Raoof Abdulfatah (Liv- ing Conditions Statistics Director, CSO) for their commitment and dedication to the project. We also acknowledge the contribution on the draft report of the members of Poverty Technical High Committee of the Government of Iraq, representatives from academic institutions, the Ministry of Planning, Education and Social Affairs, and colleagues from the Central Statistics Office and the Kurdistan Region Statistics during the Beirut workshop in October 2014. We are thankful to our peer reviewers - Kenneth Simler (Senior Economist, GPVDR) and Nobuo Yoshida (Senior Economist, GPVDR) – for their valuable comments. Finally, we acknowledge the support of TACBF Trust Fund for financing a significant part of the work and the support and encouragement of Ferid Belhaj (Country Director, MNC02), Robert Bou Jaoude (Country Manager, MNCIQ), and Pilar