An Assessment of Urban Development and Control Mechanisms in Selected Nigerian Cities Barnabas W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESS RELEASE June 25, 2021 for Immediate Release U.S. Embassy

United States Diplomatic Mission to Nigeria, Public Affairs Section Plot 1075, Diplomatic Drive, Central Business District, Abuja Telephone: 09-461-4000. Website at http://nigeria.usembassy.gov PRESS RELEASE June 25, 2021 For Immediate Release U.S. Embassy Abuja Partners Channels Academy to Train Conflict Reporters The U.S. Embassy Abuja, in partnership with Channels Academy, has trained over 150 journalists on Conflict Reporting and Peace Journalism. In her opening remarks, the U.S. Embassy Spokesperson/Press Attaché Jeanne Clark noted that the United States recognized that security challenges exist in many forms throughout the country, and that journalists are confronted with responsibility to prioritize physical safety in addition to meeting standards of objectivity and integrity in conflict. She urged the journalists to share their experiences throughout the course of the three-day seminar and encouraged participants to identify new ways to address these security challenges. The trainer Professor Steven Youngblood from the U.S. Center for Global Peace Journalism – Park University defined and presented principles for peace journalism in conflict reporting. He cautioned journalists to refrain from what he termed war journalism. He said, "war journalism is a pattern of media coverage that includes overvaluing violent, reactive responses to conflict while undervaluing non-violent, developmental responses.” The Provost of Channels Academy, Mr Kingsley Uranta, showed appreciation for the continuous partnership with the U.S. Embassy and for bringing such training opportunities to Nigerian journalists. He also called on conflict reporters to be peace ambassadors. The training took place virtually via Zoom on June 22 – 24, 2021. Journalists converged in American Spaces in Abuja, Kano, Bauchi Sokoto, Maiduguri, Awka, and Ibadan. -

“500 Children Missing in Lagos”: Child Kidnapping and Public Anxiety in Colonial Nigeria

CHAPTER 4 “500 Children Missing in Lagos”: Child Kidnapping and Public Anxiety in Colonial Nigeria Saheed Aderinto and Paul Osifodunrin Introduction The title of this chapter is a front-page headline of the July 31, 1956, issue of the West African Pilot, the best-selling newspaper in 1950s Nigeria.1 The newspaper reported the arrest of one Lamidi Alabi, accused of kidnapping three children (Ganiyu Adisa, Musibawu Adio, and Asani Afoke, all boys, between the ages of three and four) on July 30 and the tumultuous atmosphere at the Lagos Central Police Station, where he was then held. It was truly a difficult day for the police force, which tried to control a mob of over 5,000, com- posed of a “surging crowd of angry women” that wanted to lynch the 38-year-old Alabi for committing a dastardly act; among them were “several mothers” who each sought to ascertain that her child was not among the victims.2 The riot police, a special security force, had to be called in to get the outburst under control.3 The Evening Times reported that traffic at Tinubu Square “came almost to a standstill.”4 Alabi’s arrest did not end the public interest in his case. His first court appearance played host to a “record crowd” of “anxious” onlookers whose interest in the saga only increased as the police investigation and criminal proceedings progressed.5 This chapter explores the phenomenon of child abduction and public anxiety in colonial Nigeria through examination of newspaper sources supplemented with colonial archival materials. It engages the numerous circumstances under which children lost their freedom to 98 SAHEED ADERINTO AND PAUL OSIFODUNRIN kidnappers and the responses from the colonial government and Nigerians. -

50Th Anniversary Brochure

CELEBRATING THE PAST, INNOVATING THE FUTURE CELEBRATING THE PAST, INNOVATING THE FUTURE TABLE OF Julius Berger is proud to celebrate its 50th Anniversary since incorporation as CONTENTS a Nigerian Company. We commemorate this milestone with an ongoing strong commitment to our clients, staff, partners and communities. Building off 4 Chairman’s Introduction our strong history, Julius Berger will continue innovating and advancing to remain a key contributor to Nigeria’s 6 Projects Footprint growth and development. 8 Milestones & Achievements 34 Our Social Responsibility 36 Our Innovations for the Future 38 Managing Director’s Closing Note JULIUS BERGER 50 YEARS | CONTENTS 3 CELEBRATING THE PAST, INNOVATING THE FUTURE CELEBRATING THE PAST, INNOVATING THE FUTURE Since that historic moment, Julius Berger For Julius Berger, no challenge has been has continued to make huge strides, too big, no job too complex. We have Mutiu Sunmonu all the while adapting to the needs of constructed some of Nigeria’s most the country and its development goals. iconic structures and demanding Chairman Starting with a single bridge project, engineering feats; project after project, swiftly expanding into road construction, we have proven ourselves to be a followed by the construction of ports, reliable partner equipped with the dams, water supply schemes and technical knowhow and organizational industrial plants, and with the conception edge to deliver quality solutions. Such of Abuja as the Federal Capital Territory, excellence has been made possible turnkey construction -

States and Local Government Areas Creation As a Strategy of National Integration Or Disintegration in Nigeria

ISSN 2239-978X Journal of Educational and Social Research Vol. 3 (1) January 2013 States and Local Government Areas Creation as a Strategy of National Integration or Disintegration in Nigeria Bassey, Antigha Okon #!230#0Q#.02+#,2-$-!'-*-%7 !3*27-$-!'*!'#,, 4#01'27-$* 0 TTTWWV[* 0$TT– Nigeria E-mail: &X)Z&--T!-+, &,#SV^VYY[Z_YY\ Omono, Cletus Ekok #!230#0Q#.02+#,2-$-!'-*-%7 !3*27-$-!'*!'#,, 4#01'27-$* 0 Bisong, Patrick Owan #!230#0Q#.02+#,2-$-!'-*-%7 Facult$-!'*!'#,, 4#01'27-$* 0 Bassey, Umo Antigha !3*27-$1"3!2'-, ,'4#01'27-$* 0 Doi: 10.5901/jesr.2013.v3n1p237 Abstract 3&'1..#0#6+',#1122#1,"*-!*%-4#0,+#,20#1!0#2'-,',5'%#0'1-,#-$2&+(-01202#%'#1of #,130',%52'-,*',2#%02'-,T3&#,*71'15 1#"-,1#""2- 2',#"$0-+2#6 )1,"-2� 0#20'#4#" +2#0'*1T 3&# 1!-.# -$ 2&# ..#0 -� 2&, 2&# "!2'-,Q !-4#01R !-,!#.23* ,*71'1 -$ 40' *#1R 0#4'#5 -$ *-!* %-4#0,+#,2 0#as and states creation in Nigeria, rationale for States and Local 90,+#,21!0#R2&#-0#2'!*$"R!-,1#/#,!#1R!-,!*31'-,"0#!-++#,"-,T<2#0!0'2'!* #6+',2'-, -$ 2&# !-,1#/#,!#1 -$ !0#2'-, -$ 122#1 "*-!*%-4#0,+#,2 0#15hich include structural imbalance in Nigeria socio-1203!230#R.#0.#232'-,-$+',-0'27"-+',2'-,Q!-,2',3-311203%%*#$-0 national resources in terms of sharing national revenue and creation of consciousness among ethnic nationalities. State and Local government creation rather promotes National disintegration. The conclusion of &'1 ..#0 2�#$-0# "#4'2#1 1'%,'$'!,2*7 $0-+ 2&# ',2#,"" $3,!2'-, -$ 122# !0#2'-, 1 #6!2#" 7 2&# %'22-01T3&'1..#0381$3,!2'-,*&',,*8g state and local government creation in Nigeria "'2'10#!-++#""2&2&##"0*9-4#0,+#,21&-3*"',20-"3!#"-+'!'*'07.-*'!72-1-*4#2&#.0- *#+ of non-indigenes and minorities. -

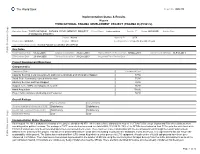

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR4370 Implementation Status & Results Nigeria THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (FADAMA III) (P096572) Operation Name: THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 7 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: (FADAMA III) (P096572) Country: Nigeria Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): National Fadama Coordination Office(NFCO) Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Jul-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date 07-Nov-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 11-Feb-2011 Effectiveness Date 23-Mar-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Capacity Building, Local Government, and Communications and Information Support 87.50 Small-Scale Community-owned Infrastructure 75.00 Advisory Services and Input Support 39.50 Support to the ADPs and Adaptive Research 36.50 Asset Acquisition 150.00 Project Administration, Monitoring and Evaluation 58.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Low Low Implementation Status Overview As at August 19, 2011, disbursement status of the project stands at 46.87%. All the states have disbursed to most of the FCAs/FUGs except Jigawa and Edo where disbursement was delayed for political reasons. The savings in FUEF accounts has increased to a total ofN66,133,814.76. 75% of the SFCOs have federated their FCAs up to the state level while FCAs in 8 states have only been federated up to the Local Government levels. -

Aquifers in the Sokoto Basin, Northwestern Nigeria, with a Description of the Genercl Hydrogeology of the Region

Aquifers in the Sokoto Basin, Northwestern Nigeria, With a Description of the Genercl Hydrogeology of the Region By HENRY R. ANDERSON and WILLIAM OGILBEE CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF AFRICA AND THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-L UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1973 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 73-600131 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Pri'ntinll Office Washinl\ton, D.C. 20402 - Price $6.75 Stock Number 2401-02389 CONTENTS Page Abstract -------------------------------------------------------- Ll Introduction -------------------------------------------------·--- 3 Purpose and scope of project ---------------------------------- 3 Location and extent of area ----------------------------------- 5 Previous investigations --------------------------------------- 5 Acknowledgments -------------------------------------------- 7 Geographic, climatic, and cultural features ------------------------ 8 Hydrology ----------------------_---------------------- __________ 10 Hydrogeology ---------------------------------------------------- 17 General features -------------------------------------------- 17 Physical character of rocks and occurrence of ground water ------- 18 Crystalline rocks (pre-Cretaceous) ------------------------ 18 Gundumi Formation (Lower Cretaceous) ------------------- 19 Illo Group (Cretaceous) ---------------------------------- -

Surviving Works: Context in Verre Arts Part One, Chapter One: the Verre

Surviving Works: context in Verre arts Part One, Chapter One: The Verre Tim Chappel, Richard Fardon and Klaus Piepel Special Issue Vestiges: Traces of Record Vol 7 (1) (2021) ISSN: 2058-1963 http://www.vestiges-journal.info Preface and Acknowledgements (HTML | PDF) PART ONE CONTEXT Chapter 1 The Verre (HTML | PDF) Chapter 2 Documenting the early colonial assemblage – 1900s to 1910s (HTML | PDF) Chapter 3 Documenting the early post-colonial assemblage – 1960s to 1970s (HTML | PDF) Interleaf ‘Brass Work of Adamawa’: a display cabinet in the Jos Museum – 1967 (HTML | PDF) PART TWO ARTS Chapter 4 Brass skeuomorphs: thinking about originals and copies (HTML | PDF) Chapter 5 Towards a catalogue raisonnée 5.1 Percussion (HTML | PDF) 5.2 Personal Ornaments (HTML | PDF) 5.3 Initiation helmets and crooks (HTML | PDF) 5.4 Hoes and daggers (HTML | PDF) 5.5 Prestige skeuomorphs (HTML | PDF) 5.6 Anthropomorphic figures (HTML | PDF) Chapter 6 Conclusion: late works ̶ Verre brasscasting in context (HTML | PDF) APPENDICES Appendix 1 The Verre collection in the Jos and Lagos Museums in Nigeria (HTML | PDF) Appendix 2 Chappel’s Verre vendors (HTML | PDF) Appendix 3 A glossary of Verre terms for objects, their uses and descriptions (HTML | PDF) Appendix 4 Leo Frobenius’s unpublished Verre ethnological notes and part inventory (HTML | PDF) Bibliography (HTML | PDF) This work is copyright to the authors released under a Creative Commons attribution license. PART ONE CONTEXT Chapter 1 The Verre Predominantly living in the Benue Valley of eastern middle-belt Nigeria, the Verre are one of that populous country’s numerous micro-minorities. -

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: an Historical Analysis, 1804-1960

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: An Historical Analysis, 1804-1960 by Kari Bergstrom Michigan State University Winner of the Rita S. Gallin Award for the Best Graduate Student Paper in Women and International Development Working Paper #276 October 2002 Abstract This paper looks at the effects of Islamization and colonialism on women in Hausaland. Beginning with the jihad and subsequent Islamic government of ‘dan Fodio, I examine the changes impacting Hausa women in and outside of the Caliphate he established. Women inside of the Caliphate were increasingly pushed out of public life and relegated to the domestic space. Islamic law was widely established, and large-scale slave production became key to the economy of the Caliphate. In contrast, Hausa women outside of the Caliphate were better able to maintain historical positions of authority in political and religious realms. As the French and British colonized Hausaland, the partition they made corresponded roughly with those Hausas inside and outside of the Caliphate. The British colonized the Caliphate through a system of indirect rule, which reinforced many of the Caliphate’s ways of governance. The British did, however, abolish slavery and impose a new legal system, both of which had significant effects on Hausa women in Nigeria. The French colonized the northern Hausa kingdoms, which had resisted the Caliphate’s rule. Through patriarchal French colonial policies, Hausa women in Niger found they could no longer exercise the political and religious authority that they historically had held. The literature on Hausa women in Niger is considerably less well developed than it is for Hausa women in Nigeria. -

AUTHOR TITLE Adult Forces

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 059 416 AC 012 155 AUTHOR Nasution, Amir H. TITLE Foreign Assistance Contribution in AdultEducation in Nigeria. INSTITUTION Ibadan Univ. (Nigeria). Inst. of AfricanAdult Education. PUB DATE Mar 71 NOTE 25p.; Paper presented to Nigerial NationalConference on Adult Education (March25-27, 1971, Lagos Univ., Lagos) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Administrative Personnel; *Adult Education;Community Agencies (Public) ;*Conferences; *Cooperative Programs; *Educational Finance; EducationalNeeds; Federal Programs; *Financial Support;*Foreign Countries; Group Activities; Mass Instruction; Organizations (Groups); Planning; PrivateAgencies; State Programs IDENTIFIERS Af r ica; *Nigeria ABSTRACT The proceedings of a nation-wideconference in Nigeria concerning adult education arepresented. The following steps are proposed in the line ofnational and international cooperation; these steps can be taken without waitingfor financial and administrative approval:(1) the registration of all kinds ofadult education programs and activities carried outby public as well as private agencies;(2) involvement of all educationpersonnel in the planning organization, and establishment of anEducation Planning Unit; (3) the formation of adult educationpriority programs, with supporting services, mass education meansand libraries, to be assisted in the context of Federal and Statesset of priorities and potentialities; and (4)the mobilization of private funds andforces on behalf of adult education.(Author/CK) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEENREPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVEDFROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIG- INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OFEDU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY. C) e--I FORE'IGNASSISTANCE CONTRIBUTION. I N LC\ ADULT EDUCATION IN NIGERIA LIJ By Amir H. -

Rail Transportation Data

Rail Transportation Data (Q1 2019) Report Date: May 2019 Data Source: National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) Contents Executive Summary 1 Number of Passengers 2 Volume of Goods/Cargo (Tons) 3 Revenue Generated from Passenger (N) 4 Revenue Generated from Goods/Cargo (N) 5 Other Income Receipt (N) 6 Methodology 7 Definition of Terms 8 Appendix 9 Acknowledgment and Contact 10 Executive Summary The rail transportation data for Q1 2019 reflected that a total of 723,995 passengers travelled via the rail system in Q1 2019 as against 748,345 passenger recorded in Q1 2018 and 746,739 in Q4 2018 representing -3.25% decline YoY and -3.05% decline QoQ respectively. Similarly, a total of 54,099 tons of volume of goods/cargo travelled via the rail system in Q1 2019 as against 79,750 recorded in Q1 2018 and 68,716 in Q4 2018 representing -32.16% decline YoY and -21.27% decline QoQ respectively. Revenue generated from passengers in Q1 2019 was put at N520,794,143 as against N507,495,503 in Q4 2018. Similarly, revenue generated from goods/cargo in Q1 2019 was put at N102,585,926 as against N84,408,861 in Q4 2018. 1 Rail Transportation Data - Q1 2019 Rail Transportation Data - Q1 2019 Number of Passengers 2019 Q on Q Y on Y % Change QRT 1 % Change (3.05) 723,995 (3.25) 2018 QRT 1 QRT 2 QRT 3 QRT 4 748,345 730,289 794,316 746,739 TOTAL 3,019,689 12 Rail Transportation Data - Q1 2019 Rail Transportation Data - Q1 2019 Volume of Goods/Cargo (Tons) 2019 Q on Q Y on Y % Change QRT 1 % Change (21.27) 54,099 (32.16) 2018 QRT 1 QRT 2 QRT 3 QRT 4 79,750 85,816 94,352 -

Nigeria Update to the IMB Nigeria

Progress in Polio Eradication Initiative in Nigeria: Challenges and Mitigation Strategies 16th Independent Monitoring Board Meeting 1 November 2017 London 0 Outline 1. Epidemiology 2. Challenges and Mitigation strategies SIAs Surveillance Routine Immunization 3. Summary and way forward 1 Epidemiology 2 Polio Viruses in Nigeria, 2015-2017 Past 24 months Past 12 months 3 Nigeria has gone 13 months without Wild Polio Virus and 11 months without cVDPV2 13 months without WPV 11 months – cVDPV2 4 Challenges and Mitigation strategies 5 SIAs 6 Before the onset of the Wild Polio Virus Outbreak in July 2016, there were several unreached settlements in Borno Borno Accessibility Status by Ward, March 2016 # of Wards in % Partially LGAs % Fully Accessible % Inaccessible LGA Accessible Abadam 10 0% 0% 100% Askira-Uba 13 100% 0% 0% Bama 14 14% 0% 86% Bayo 10 100% 0% 0% Biu 11 91% 9% 0% Chibok 11 100% 0% 0% Damboa 10 20% 0% 80% Dikwa 10 10% 0% 90% Gubio 10 50% 10% 40% Guzamala 10 0% 0% 100% Gwoza 13 8% 8% 85% Hawul 12 83% 17% 0% Jere 12 50% 50% 0% Kaga 15 0% 7% 93% Kala-Balge 10 0% 0% 100% Konduga 11 0% 64% 36% Kukawa 10 20% 0% 80% Kwaya Kusar 10 100% 0% 0% Mafa 12 8% 0% 92% Magumeri 13 100% 0% 0% Maiduguri 15 100% 0% 0% Marte 13 0% 0% 100% Mobbar 10 0% 0% 100% Monguno 12 8% 0% 92% Ngala 11 0% 0% 100% Nganzai 12 17% 0% 83% Shani 11 100% 0% 0% State 311 41% 6% 53% 7 Source: Borno EOC Data team analysis Four Strategies were deployed to expand polio vaccination reach and increase population immunity in Borno state SIAs RES2 RIC4 Special interventions 12 -

Using Geographical Information System (GIS) Techniques in Mapping Traffic Situation Along Selected Road Corridors in Lagos Metropolis, Nigeria

Research on Humanities and Social Sciences www.iiste.org ISSN (Paper)2224-5766 ISSN (Online)2225-0484 (Online) Vol.5, No.10, 2015 Using Geographical Information System (GIS) Techniques in Mapping Traffic Situation along Selected Road Corridors in Lagos Metropolis, Nigeria Adebayo. H. Oluwasegun Department of Geography & Regional Planning,Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, Ogun State Email: [email protected] Abstract Moving from one point to another in any city in the World is an endurance test, regardless of income or social status, the conditions under which people travel is becoming more and more difficult. The traffic situation in Lagos Metropolis is no different. In this paper, effort has been made to map out traffic situations along selected corridors in Lagos Metropolis, Nigeria using Geographical Information System Techniques. The data used in this study were obtained from Lagos Metropolitan Area Transport Authority (LAMATA) agency, topographical and road map of Lagos metropolis from Lagos state ministry of Land s and Survey and Lagos state ministry of Transport. In addition, primary data include the geographic coordinates of the selected traffic corridors using GPS (Global Positioning System), observation of the nature of vehicular traffic congestion and traffic counts along the corridors. The data obtained was entered and used to developed traffic situation information system (TSIS). Data retrieved and spatial analysis from attributes were shown using ArcGIS 10. The results were presented in map format which makes for easy interpretation and quick decision-making. Geographic Information System is an effective tool to display different levels of congestion and vehicular volume along digital traffic corridors.