The Sun Is ZERO” Light and Color As Principles 7 of Structural Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Architectural Theory and Practice, and the Question of Phenomenology

Architectural Theory and Practice, and the Question of Phenomenology (The Contribution of Tadao Ando to the Phenomenological Discourse) Von der Fakultät Architektur, Bauingenieurwesen und Stadtplanung der Brandenburgischen Technischen Universität Cottbus zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktor-Ingenieurs genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Mohammadreza Shirazi aus Tabriz, Iran Gutachter: : Prof. Dr. Eduard Führ Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Karsten Harries Gutachter: Gastprofessor. Dr. Riklef Rambow Tag der Verteidigung: 02. Juni 2009 Acknowledgment My first words of gratitude go to my supervisor Prof. Führ for giving me direction and support. He fully supported me during my research, and created a welcoming and inspiring atmosphere in which I had the pleasure of writing this dissertation. I am indepted to his teachings and instructions in more ways than I can state here. I am particularly grateful to Prof. Karsten Harries. His texts taught me how to think on architecture deeply, how to challenge whatever is ‘taken for granted’ and ‘remain on the way, in search of home’. I am also grateful to other colleagues in L.S. Theorie der Architektur. I want to express my thanks to Dr. Riklef Rambow who considered my ideas and texts deeply and helped me with his advice at different stages. I am thankful for the comments and kind helps I received from Dr. Katharina Fleischmann. I also want to thank Prof. Hahn from TU Dresden and other PhD students who attended in Doktorandentag meetings and criticized my presentations. I would like to express my appreciation to the staff of Langen Foundation Museum for their kind helps during my visit of that complex, and to Mr. -

The Authenticity of Ambiguity: Dada and Existentialism

THE AUTHENTICITY OF AMBIGUITY: DADA AND EXISTENTIALISM by ELIZABETH FRANCES BENJAMIN A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham August 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ii - ABSTRACT - Dada is often dismissed as an anti-art movement that engaged with a limited and merely destructive theoretical impetus. French Existentialism is often condemned for its perceived quietist implications. However, closer analysis reveals a preoccupation with philosophy in the former and with art in the latter. Neither was nonsensical or meaningless, but both reveal a rich individualist ethics aimed at the amelioration of the individual and society. It is through their combined analysis that we can view and productively utilise their alignment. Offering new critical aesthetic and philosophical approaches to Dada as a quintessential part of the European Avant-Garde, this thesis performs a reassessment of the movement as a form of (proto-)Existentialist philosophy. The thesis represents the first major comparative study of Dada and Existentialism, contributing a new perspective on Dada as a movement, a historical legacy, and a philosophical field of study. -

Annual Report 2017

2017 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT 2017 2,522 EMPLOYEES FROM 71NATIONS WORKED IN 38 COUNTRIES AND OVERSEAS PROGRAMMES IN 2017. 410 WITH MILLION EUROS OF FUNDING 229.4 WE SUPPORTED MILLION PEOPLE IN ORDER 11. 8 TO ACHIEVE 1 GOAL : Interview with Supervisory Board and Executive Board 6 WHAT WE Zero Hunger Requires Political Measures 8 WANT Welthungerhilfe's Vision 52 Project Map 10 WHAT WE Congo: Better Harvests for a Brighter Future 12 Bangladesh: The Suffering of the Rohingya 14 ACHIEVE Nepal: Fast Reaction thanks to Good Preparation 16 Sierra Leone: Creating Professional Prospects with “Skill Up!” 18 Horn of Africa: Prepared for Drought 20 New Approach: Securing Water Sustainably 22 Transparency and Impact 24 Impact Chain 27 Holding Politics Accountable 28 Campaigns and Events 2017 30 Outlook for 2018: Tapping into Potentials 48 Thank You to Our Supporters 50 This Is How We Collect Donations 51 Welthungerhilfe’s Structure 32 WHO WE ARE Forging ahead with the foundation 44 Welthungerhilfe’s Networks 47 Balance Sheet 34 FACTS AND Income and Expenditure Account 37 Income and Expenditure Account in Accordance with DZI 39 FIGURES Welthungerhilfe in Numbers 40 All Overseas Programmes 2017 42 Annual Financial Statement Foundation 46 PUBLICATION DETAILS Publisher: Order number p. 22: Thomas Rommel/WHH; pp. 23, The DZI donation Deutsche Welthungerhilfe e. V. 460-9549 24: WHH; p. 26 t./b.: Iris Olesch; p. 28: seal certifies Friedrich-Ebert-Straße 1 Deutscher Bundes tag/Trutschel; p. 29 t. l.: Welthungerhilfe‘s efficient and 53173 Bonn Cover photo Engels & Krämer GmbH; p. 29 t. r.: responsible Tel. -

Program Site Landscape and Building

Location: near Neuss, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Architect: Tadao Ando (Japan) Date: 2002.8-2004.7 Site Site: On the grounds of the Museum Insel Hombroich; 1,040 Acres Langen Foundation Case Study Material: Reinforced concrete; Glass; steel. Program: Museum Program The Langen Foundation is located at the Raketenstation Hombroich, a former NATO base, in the midst of the idyllic landscape of 1,040 acres of land is being planned for an experiment in living with nature, where architects and artists from this list each envision his or her own program and its accompanying design. This lat- Japanese collection space the Hombroich cultural environment. ter effort, coordinated by the Berlin architectural office of Hoidn Wang Partner, is known as the “Hombroich spaceplacelab,” and requires that at least 90 percent of each site be left for nature. The simple shape of space inside makes people to be peaceful and Ando got involved with the art program at Hombroich through the instigation of Müller, who knew of Ando’s museums in Japan and the United States Ando’s crafted concrete geometric forms interact compellingly Visitors enter through a cut-out in the semicircular concrete wall, opening up the view to the glass, steel and concrete building. with light, water, and earth in a manner that fits in with the Hombroich identity. In 1995, Ando designed an art pavilion for Müller on the former missile base; it appealed to another German art collector, Marianne focus on the art collections. Langen, who was searching for a home for the art that she had amassed with her late husband, Viktor, a businessman, which they had housed in Switzerland. -

Olafur Eliasson Biography

Olafur Eliasson Biography 1967 Born in Copenhagen 1989 – 1995 Studied at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen Lives in Copenhagen and Berlin Solo Exhibitions 2019 Olafur Eliasson: In real life, Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom, July 11, 2019 – January 5, 2020. Travel to Guggenheim Bilbao, Spain, February 14, 2020 – June 21, 2021. Tree of Codes, Opéra Bastille, Paris, France, June 26 – July 13. Y/our future is now, The Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art, Porto, Portugal, July 31, 2019 – June 14, 2020. 2018 Objets définis par l’activité, Espace Muraille, Genève, Switzerland, January 24 — April 28. Una mirada a lo que vendrá (A view of things to come), Galería Elvira González, Madrid, Spain, February 13 – April 28. Reality Projector, Marciano Art Foundation, Los Angeles, USA, March 1 – August 25. The unspeakable openness of things, Red Brick Art Museum, Beijing, People’s Republic of China, March 25 – August 12. Multiple Shadow House, Danish Achitecture Center (DAC), Copenhagen, Denmark, May 17 – Oktober 21. Olafur Eliasson: WASSERfarben (WATERcolours) , Graphische Sammlung – Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, Germany, June 7 – September 2. The speed of your attention, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles, September 15 – December 22. 2017 Olafur Eliasson, Fischli/Weiß, Art Project Ibiza & Lune Rouge, Ibiza, Spain, January 21 – April 29. Olafur Eliasson: Pentagonal landscapes, EMMA – Espoo Museum of Modern Art, Espoo, Finnland, February 8 – May 21. Olafur Eliasson: Green light – An artistic workshop, The Moody Center of the Arts, Houston, Texas, USA, February 24 – Mid May. Olafur Eliasson: The listening dimension, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, March 23 – April 22. -

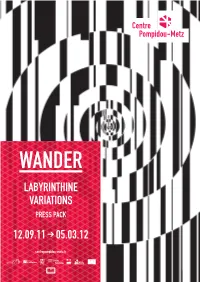

Labyrinthine Variations 12.09.11 → 05.03.12

WANDER LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS PRESS PACK 12.09.11 > 05.03.12 centrepompidou-metz.fr PRESS PACK - WANDER, LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION .................................................... 02 2. THE EXHIBITION E I TH LAByRINTH AS ARCHITECTURE ....................................................................... 03 II SpACE / TImE .......................................................................................................... 03 III THE mENTAL LAByRINTH ........................................................................................ 04 IV mETROpOLIS .......................................................................................................... 05 V KINETIC DISLOCATION ............................................................................................ 06 VI CApTIVE .................................................................................................................. 07 VII INITIATION / ENLIgHTENmENT ................................................................................ 08 VIII ART AS LAByRINTH ................................................................................................ 09 3. LIST OF EXHIBITED ARTISTS ..................................................................... 10 4. LINEAgES, LAByRINTHINE DETOURS - WORKS, HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOgICAL ARTEFACTS .................... 12 5.Om C m ISSIONED WORKS ............................................................................. 13 6. EXHIBITION DESIgN ....................................................................................... -

Marianne Boesky Gallery Frank Stella

MARIANNE BOESKY GALLERY NEW YORK | ASPEN FRANK STELLA BIOGRAPHY 1936 Born in Malden, MA Lives and works in New York, NY EDUCATION 1950 – 1954 Phillips Academy (studied painting under Patrick Morgan), Andover, MA 1954 – 1958 Princeton University (studied History and Art History under Stephen Greene and William Seitz), Princeton, NJ SELECTED SOLO AND TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2021 Brussels, Belgium, Charles Riva Collection, Frank Stella & Josh Sperling, curated by Matt Black September 8 – November 20, 2021 [two-person exhibition] 2020 Ridgefield, CT, Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Frank Stella’s Stars, A Survey, September 21, 2020 – September 6, 2021 Tampa, FL, Tampa Museum of Art, Frank Stella: What You See, April 2 – September 27, 2020 Tampa, FL, Tampa Museum of Art, Frank Stella: Illustrations After El Lissitzky’s Had Gadya, April 2 – September 27, 2020 Stockholm, Sweeden, Wetterling Gallery, Frank Stella, March 19 – August 22, 2020 2019 Los Angeles, CA, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Frank Stella: Selection from the Permanent Collection, May 5 – September 15, 2019 New York, NY, Marianne Boesky Gallery, Frank Stella: Recent Work, April 25 – June 22, 2019 Eindhoven, The Netherlands, Van Abbemuseum, Tracking Frank Stella: Registering viewing profiles with eye-tracking, February 9 – April 7, 2019 2018 Tuttlingen, Germany, Galerie der Stadt Tuttlingen, FRANK STELLA – Abstract Narration, October 6 – November 25, 2018 Los Angeles, CA, Sprüth Magers, Frank Stella: Recent Work, September 14 – October 26, 2018 Princeton, NJ, Princeton University -

Aus Datenschutz- Bzw. Urheberrechtlichen Gründen Erfolgt Die Publikation Mit Anonymisierung Von Namen Und Ohne Abbildungen

Provenienzbericht zu Pablo Picasso, „Tête de femme, de profil“, 40,9 x 37,5 cm (Lostart-ID: 533083) Version nach Review v. 20.03.2018 ǀ Projekt Provenienzrecherche Gurlitt (Stand: 17.09.2017) Aus datenschutz- bzw. urheberrechtlichen Gründen erfolgt die Publikation mit Anonymisierung von Namen und ohne Abbildungen. © A. W. © A. W. Abschlussbericht zu Lostart-ID: 533083 - Pablo Picasso: Tête de femme, de profil Ev-Isabel Raue 1. Daten Künstler Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) Titel Tête de femme, de profil (vgl. WVZ) Alternativer Titel Frauenkopf im Profil (vgl. Ausst.kat. Barcelona/Bern 1992) Maße 40,9 x 37,5 cm (Blattgröße) [vgl. Zustandsprotokolle] Technik Kaltnadelradierung [?] [Papierart ?] Wasserzeichen / Signatur / Datierung der Druckplatte 1905 Befund der Blattvorderseite Beschriftung: a) Unten links handschriftlich in Bleistift [?]: „G. 7.“ [Beschriftung bezieht sich vermutlich auf das WVZ von Bernhard Geiser bzw. von Geiser/Baer.] b) Unten rechts handschriftlich in Bleistift [?]: „350.- „ Seite 1 von 17 Provenienzbericht zu Pablo Picasso, „Tête de femme, de profil“, 40,9 x 37,5 cm (Lostart-ID: 533083) Version nach Review v. 20.03.2018 ǀ Projekt Provenienzrecherche Gurlitt (Stand: 17.09.2017) [Verkaufspreis der Kunsthandlung Aug. Klipstein vorm. Gutekunst & Klipstein, Bern] c) Unten rechts Prägestempel: „L. Fort Imprimeur Paris“ Rückseitenbefund Beschriftung: a) Unten links in Bleistift: „B/32“ [umrahmt] b) Unten links in Bleistift: „350.-“ [Verkaufspreis der Kunsthandlung Aug. Klipstein vorm. Gutekunst & Klipstein, Bern] c) Unten links in Bleistift: „180_83“ d) Mitte in Bleistift: „05937“ [Bestands-Nr. der Kunsthandlung Aug. Klipstein vorm. Gutekunst & Klipstein, Bern] Werkverzeichnisse (WVZ) a) Bloch 1968, S. 21, Kat.-Nr. 6. b) Geiser/Baer 1990, Bd. -

John Anthony Thwaites (1909-1981)

Originalveröffentlichung in: Zuschlag, Christoph (Hrsg.): Brennpunkt Informel : Quellen, Strömungen, Reaktionen; [Ausstellung Brennpunkt Informel des Kurpfälzischen Museums der Stadt Heidelberg...], Köln 1998, S. 166-172 Christoph Zuschlag »Vive la critique engagee!« Kunstkritiker der Stunde Null: John Anthony Thwaites (1909-1981) »Heu te will uns scheinen, daß er in Deutschland neben Albert Schulze Vellinghausen wohl die bedeutendste Kritiker-Figur der fünfziger Jahre gewesen ist.« Walter Vitt hat in seinem Nachruf auf John Anthony Thwaites im Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger vom 23. November 1981 nicht übertrieben. Im Zusammenhang mit der westdeutschen Kunstszene der 50er und 60er Jahre begegnet man immer wieder dem Namen John Anthony Thwaites (Abb.). Obwohl Thwaites in Tageszeitungen und Zeitschriften, Katalogen und Monographien, in Vorträgen und im Rundfunk regelmäßig an die Öffentlichkeit trat, obwohl er zahlreiche heute anerkannte Künstler über Jahrzehnte publizistisch begleitete, beschränken sich die Angaben über ihn in der Literatur auf knappe Erwähnungen. Der vorliegende Aufsatz möchte erstmals ausführlicher mit Thwaites' Biographie, seinem kunstkritischen Werk und dessen Bedeutung bekannt machen. Grundlage sind zum einen die Veröffentlichungen des Kritikers, zum anderen die Unterlagen in seinem Archiv, das sich im Besitz des Sohnes, Barnabas Thwaites, befindet. Es umfaßt Manuskripte von gedruckten und ungedruckten Texten, Publikationen, Presseausschnitte, Photographien, persönliche Aufzeichnungen und umfangreiche Korrespondenzen mit Künstlern, -

ZERO ERA Mack and His Artist Friends

PRESS RELEASE: for immediate publication ZERO ERA Mack and his artist friends 5th September until 31st October 2014 left: Heinz Mack, Dynamische Struktur schwarz-weiß, resin on canvas, 1961, 130 x 110 cm right: Otto Piene, Es brennt, Öl, oil, fire and smoke on linen, 1966, 79,6 x 99,8 cm Beck & Eggeling presents at the start of the autumn season the exhibition „ZERO ERA. Mack and his artist friends“ - works from the Zero movement from 1957 until 1966. The opening will take place on Friday, 5th September 2014 at 6 pm at Bilker Strasse 5 and 4-6 in Duesseldorf, on the occasion of the gallery weekend 'DC Open 2014'. Heinz Mack will be present. After ten years of intense and successful cooperation between the gallery and Heinz Mack, culminating in the monumental installation project „The Sky Over Nine Columns“ in Venice, the artist now opens up his private archives exclusively for Beck & Eggeling. This presents the opportunity to delve into the ZERO period, with a focus on the oeuvre of Heinz Mack and his relationship with his artist friends of this movement. Important artworks as well as documents, photographs, designs for invitations and letters bear testimony to the radical and vanguard ideas of this period. To the circle of Heinz Mack's artist friends belong founding members Otto Piene and Günther Uecker, as well as the artists Bernard Aubertin, Hermann Bartels, Enrico Castellani, Piero BECK & EGGELING BILKER STRASSE 5 | D 40213 DÜSSELDORF | T +49 211 49 15 890 | [email protected] Dorazio, Lucio Fontana, Hermann Goepfert, Gotthard Graubner, Oskar Holweck, Yves Klein, Yayoi Kusama, Walter Leblanc, Piero Manzoni, Almir da Silva Mavignier, Christian Megert, George Rickey, Jan Schoonhoven, Jesús Rafael Soto, Jean Tinguely and Jef Verheyen, who will also be represented in this exhibition. -

Otto Piene: Lichtballett

Otto Piene: Lichtballett a complete rewiring of the piece, removal of surface damage and dents, and team of artists for documenta 6, was later exhibited on the National Mall in replacement of the light fixtures and bulbs to exact specifications. Washington, DC. For the closing ceremony of the 1972 Munich Olympics, The MIT List Visual Arts Center is pleased to present an exhibition of the Piene created Olympic Rainbow, a “sky art” piece comprised of five helium- light-based sculptural work of Otto Piene (b. 1928, Bad Laasphe, Germany). The exhibition also showcases several other significant early works filled tubes that flew over the stadium. Piene received the Sculpture Prize Piene is a pioneering figure in multimedia and technology-based art. alongside new sculptures. The two interior lamps of Light Ballet on Wheels of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1996. He lives and works in Known for his smoke and fire paintings and environmental “sky art,” Piene (1965) continuously project light through a revolving disk. The sculpture Groton, Massachusetts, and Düsseldorf, Germany. formed the influential Düsseldorf-based Group Zero with Heinz Mack in Electric Anaconda (1965) is composed of seven black globes of decreasing the late 1950s. Zero included artists such as Piero Manzoni, Yves Klein, Jean diameter stacked in a column, the light climbing up until completely lit. Tinguely, and Lucio Fontana. Piene was the first fellow of the MIT Center Piene’s new works produced specifically for the exhibition, Lichtballett for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) in 1968, succeeding its founder György (2011), a site-specific wall sculpture, and One Cubic Meter of Light Black Kepes as director until retiring in 1994. -

Kusama 2 1 Zero Gutai Kusama

ZERO GUTAI KUSAMA 2 1 ZERO GUTAI KUSAMA VIEWING Bonhams 101 New Bond Street London, W1S 1SR Sunday 11 October 11.00 - 17.00 Monday 12 October 9.00 - 18.00 Tuesday 13 October 9.00 - 18.00 Wednesday 14 October 9.00 - 18.00 Thursday 15 October 9.00 - 18.00 Friday 16 October 9.00 - 18.00 Monday 19 October 9.00 - 17.00 Tuesday 20 October 9.00 - 17.00 EXHIBITION CATALOGUE £25.00 ENQUIRIES Ralph Taylor +44 (0) 20 7447 7403 [email protected] Giacomo Balsamo +44 (0) 20 7468 5837 [email protected] PRESS ENQUIRIES +44 (0) 20 7468 5871 [email protected] 2 1 INTRODUCTION The history of art in the 20th Century is punctuated by moments of pure inspiration, moments where the traditions of artistic practice shifted on their foundations for ever. The 1960s were rife with such moments and as such it is with pleasure that we are able to showcase the collision of three such bodies of energy in one setting for the first time since their inception anywhere in the world with ‘ZERO Gutai Kusama’. The ZERO and Gutai Groups have undergone a radical reappraisal over the past six years largely as a result of recent exhibitions at the New York Guggenheim Museum, Berlin Martin Gropius Bau and Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum amongst others. This escalation of interest is entirely understandable coming at a time where experts and collectors alike look to the influences behind the rapacious creativity we are seeing in the Contemporary Art World right now and in light of a consistently strong appetite for seminal works.