Inclusion Matters for Resilience in South Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Minorities in Pakistan

Abdul Majid* RELIGIOUS MINORITIES IN PAKISTAN Abstract The Constitution describes Pakistan as an “Islamic State”. It is a predominately Muslim State but there are several non-Muslims groups living here as citizens. Pakistan’s Constitution stands for equality of all citizens irrespective of religion, caste, region, tribe language and gender. Islam the state religion of Pakistan stands for respect and toleration for all religions. This paper examines the population and constitutional position of religious minorities in Pakistan. It also provides a general picture of major religious communities the Hindus, the Christians and the Sikhs. The paper also explains the Ahmadya community was declared a minority in September 1947. Despite the handicap of small population, Pakistan’s religious minorities have freedom to practice their religion and pursue their cultural heritage. Key Words: All India Muslim League, PPP, 1973 constitution, Lahore resolution, Jammat-e-Islami, Makkah, Pakistan Hindus Welfare Association Introduction All resolutions of the All India Muslim League since 1940 made categorical commitments for granting religious and cultural freedom to all religious minorities. In Pakistan Minority community is able to assert that it is completely safe. For all those who are guided by reason and humankind’s becoming a modern, civilized and responsible state. The ethnic communities and diverse cultures included Punjabi, Baloch, Sindhi, Seraiki and similarly beside Islam, the believers of Hindu, Sikh, Christian and others religious were also living in Pakistan. The cultural diversity of the country is under threat and religious minorities and various ethnic communities are being denied rights and Identity. Pakistan was established in August 1947 as a homeland for the Muslims of British India. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXX NO. 9-10 APRIL - MAY - 2014 PRADEEP KUMAR JENA, I.A.S. Principal Secretary PRAMOD KUMAR DAS, O.A.S.(SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Odishan Breakfast for the Trinity Pramod Chandra Pattnayak ... 1 Government of India Act, 1935 and His Majesty's Order-in-Council for Formation of Modern Odisha Dr. Janmejaya Choudhury ... 6 Stipulation through Socio-Eco-Political Fortitude: Stature of Separate Odisha Province Snigdha Acharya ... 10 Contribution of Ramchandra Mardaraj for the Formation of New Odisha Dr. Dasarathi Bhuiyan ... 16 Role of Venketeshwar Deo on Odia Movement Chittaranjan Mishra ... 30 Utkalmani Gopabandhu : The Man and His Mission Dr. Saroj Kumar Panda ... 32 Madhusudan Das : Icon of Odia Pride Rabindra Kumar Behuria ... 34 April 27: What it means to South Africans Bishnupriya Padhi ... 38 Satavahana Kings : Ruling in Odisha Akhil Kumar Sahoo .. -

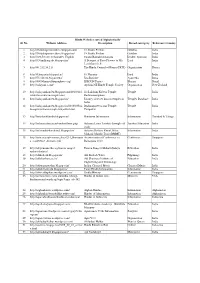

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Weaponisation of Religion Dr Ramesh Raina

WEAPONISATION OF RELIGION DR RAMESH RAINA The weaponisation of religion has a long history.Partition of India provided a fertile ground and a platform in the form of Pakistan to practice this to the hilt.The story that developed in Pakistan thereafter is all about hardening of religious edges whose natural corollary is the toxic anti-minority sentiment resulting in total social transformation of the society.To practice the supremacy of religion in public life,It turned out to be a manna from heaven for the religious hardliners.The centuries old protracted battle both political,social and legal and the demolition of Babri Masjid in India was used as an instrument for the hardened attitudes of the people of Pakistan to vent their ire on the hapless hindu minority which increased the pace of forced conversion of girls,demolition of temples and a strident minority hatred. Muslim politics in Pakistan is best understood by its policies towards the religious minorities which is a toxic mix of hate ideology resultantly being treated as second class citizens. It finds expression by instilling recurrent insecurity in them and squeezing their religious space which adversely affects the freedom to practice their religion openly.There is an uninterrupted continuity in such policies best exemplified by the fact that there are only 31 temples functional out of 1288 pre-partition temples registered with Pakistan Evacuee Trust Board.Not only that the 16th century Ram Mandir Islamabad has been reduced to a tourist spot and hindus are not allowed to worship there. The recent destruction of hindu temple site at Islamabad is yet another example of persistent discrimination faced by hindu community in Pakistan. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Religions and Development Research Programme

Religions and Development Research Programme Mapping the Terrain: The Activities of Faith-based Organizations in Development in Pakistan Muhammad Asif Iqbal Saima Siddiqui Social Policy and Development Centre, Karachi Working Paper 24- 2008 Religions and Development Research Programme The Religions and Development Research Programme Consortium is an international research partnership that is exploring the relationships between several major world religions, development in low-income countries and poverty reduction. The programme is comprised of a series of comparative research projects that are addressing the following questions: z How do religious values and beliefs drive the actions and interactions of individuals and faith-based organisations? z How do religious values and beliefs and religious organisations influence the relationships between states and societies? z In what ways do faith communities interact with development actors and what are the outcomes with respect to the achievement of development goals? The research aims to provide knowledge and tools to enable dialogue between development partners and contribute to the achievement of development goals. We believe that our role as researchers is not to make judgements about the truth or desirability of particular values or beliefs, nor is it to urge a greater or lesser role for religion in achieving development objectives. Instead, our aim is to produce systematic and reliable knowledge and better understanding of the social world. The research focuses on four countries (India, Pakistan, Nigeria and Tanzania), enabling the research team to study most of the major world religions: Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Buddhism and African traditional belief systems. The research projects will compare two or more of the focus countries, regions within the countries, different religious traditions and selected development activities and policies. -

Tuberculosis, Care and Subjectivity at the Margins of Rajasthan. The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Harvard University - DASH Troubling Breath: Tuberculosis, care and subjectivity at the margins of Rajasthan. The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. McDowell, Andrew James. 2014. Troubling Breath: Tuberculosis, Citation care and subjectivity at the margins of Rajasthan.. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Accessed April 17, 2018 4:59:13 PM EDT Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12274306 This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH Terms of Use repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA (Article begins on next page) Troubling Breath: Tuberculosis, Care and Subjectivity at the Margins of Rajasthan A dissertation presented by Andrew James McDowell to The Department of Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Anthropology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2014 © 2014–Andrew James McDowell All rights reserved. Arthur Kleinman, Byron Good Andrew James McDowell Troubling Breath: Tuberculosis, Care and Subjectivity at the Margins of Rajasthan Abstract “Troubling Breath,” the product of fourteen months of fieldwork, examines the experience of tuberculosis sufferers in rural Rajasthan, India. In it, I engage the Indian national tuberculosis control program, local health institutions, informal biomedical providers, non-biomedical healers and sufferers to consider how global tuberculosis control initiatives interact with social life and subjectivity among the rural poor. -

Dated Figure of King Jayavarma, the Tradition of Figure Making and the Historical Importance of This Discovery

Dated Figure of King Jayavarma, The Tradition of Figure Making and The Historical Importance of This Discovery - Tara Nanda Mishra During the month of May 1992, while digging broke the figure into several pieces. But now it has the foundation for a modem house in the Machagala been beautifully repaired and displayed in the art area (Children Burial Place) of Maligaon, about gallery of National Museum at Chhawani, hundred meter west of the place, from where the so Kathmandu. The figure from head to feet is thus called Yaksha image was discovered in 1965 by the completely restored, except the right hand after the present writer, excavating before the Manmaneshwari upper arm (the wrist, palm and fingers) which have temple, wonderful discovery of a figure of King been broken and lost for ever. This huge life size Jayavarma had been made. This figure has been figure measures 174 cm (5 feet 3 and half inches) in carved over a pale sandstone. The figure belongs to height and 71 cm. (28 inches, near the two elbows) to the Kushan. This is the earliest pre-Lichhavi figure 49.5 cm (19 and half inches) broader at the pedestal. having inscription on its pedestal in Brahmi Script It has been carved over a single piece of stone and in sanskrit language. It bears the date in Saka It is to be noted here that the area from where Samvat 107 (A.D. 185). Thus it has become the first the figure has been found, is historically very dated image as well as the first historical epigraphic important. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Persecution of Pakistani Hindus

Contents On the catalogue of injuries faced by religious minorities in Pakistan ...................................... 3 ‗Pakistan schools teach Hindu hatred‘ ....................................................................................... 7 How to Have Cheaper Insulation for Your Home Windows and Doors (DrPrem) ................... 7 2. 5,000 Hindus flee Pak every year due to persecution‘ ........................................................... 8 Hindus feel ignored in decision-making process ....................................................................... 9 Pakistan: A Hell for Hindus and Religious Shrines - Is Nawaz Sharif Listening? .................. 10 Hindus in Pakistan – A People Without a Voice ..................................................................... 10 1,400 Hindu sites in dire need of govt protection: Pakistan Hindu Council ............................ 12 Hindu council urges PM to prevent atrocities against minorities ............................................ 12 Our hopes were dashed, say Pakistani Hindus ......................................................................... 13 Voices of two minority groups echo at KPC on Thursday ...................................................... 16 Christian couple burned to death over ‗blasphemy‘ ................................................................. 19 Hindu girls subjected to forced conversion: Motumal ............................................................. 20 Ready to pay Jaziya to Bilawal, Raj Kumar reiterates as one more under teen