CENTRE for APPLIED SOCIAL SCIENCES * By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020

Statutory Instrument 55 ofS.I. 2020. 55 of 2020 Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) [CAP. 23:02 Order, 2020 (No. 20) Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) “THIRTEENTH SCHEDULE Order, 2020 (No. 20) CUSTOMS DRY PORTS IT is hereby notifi ed that the Minister of Finance and Economic (a) Masvingo; Development has, in terms of sections 14 and 236 of the Customs (b) Bulawayo; and Excise Act [Chapter 23:02], made the following notice:— (c) Makuti; and 1. This notice may be cited as the Customs and Excise (Ports (d) Mutare. of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020 (No. 20). 2. Part I (Ports of Entry) of the Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) Order, 2002, published in Statutory Instrument 14 of 2002, hereinafter called the Order, is amended as follows— (a) by the insertion of a new section 9A after section 9 to read as follows: “Customs dry ports 9A. (1) Customs dry ports are appointed at the places indicated in the Thirteenth Schedule for the collection of revenue, the report and clearance of goods imported or exported and matters incidental thereto and the general administration of the provisions of the Act. (2) The customs dry ports set up in terms of subsection (1) are also appointed as places where the Commissioner may establish bonded warehouses for the housing of uncleared goods. The bonded warehouses may be operated by persons authorised by the Commissioner in terms of the Act, and may store and also sell the bonded goods to the general public subject to the purchasers of the said goods paying the duty due and payable on the goods. -

WWF World Wide Fund for Nature

WWF World Wide Fund For Nature Centre For Applied Social Sciences CHANGING LAND-USE IN THE EASTERN ZAMBEZI VALLEY: SOCIO-ECONOMIC CONSIDERATIONS By Bill Derman Department of Anthropology & African Studies Centre Michigan State University December 22 1995 Printed October 1996 CASS/WWF Joint Paper Report submitted to: Centre for Applied Social Sciences WWF - World Wide Fund for Nature University of Zimbabwe Programme Office - Zimbabwe P O Box MP 167 P O Box CY 1409 Mount Pleasant Causeway HARARE HARARE Zimbabwe Zimbabwe Members of IUCN - The World Conservation Union The opinions and conclusions of this Joint Paper are not necessarily those of the Centre for Applied Social Sciences, University of Zimbabwe or the WWF - World Wide Fund for Nature. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ................ ii INTRODUCTION ............... 1 PART 1 The Eastern Zambezi Valley: An Historical Overview . 4 PART 2 Development Interventions in the Eastern Valley . 13 PART 3 Non-Governmental Organisations ...... 19 PART 4 Migration and Migrants ......... 22 PART 5 Local Responses to Change ........ 26 PART 6 New and Planned Development Initiatives .. 32 PART 7 The Organisational Environment ...... 46 PART 8 Policy and Land Use Planning ....... 50 ENDNOTES ............. 52 BIBLIOGRAPHY .............. 57 PREFACE This study by Professor Bill Derman is intended to provide an overview of socio- economic dimensions which have influenced, and often controlled, land use in the eastern Zambezi Valley of Zimbabwe. The study also provides a wider contextual framework to several more detailed studies of the ecological, economic and social components of land use, agriculture, and natural resource use and management being undertaken by CASS and WWF. Much of this work is in support of Zimbabwe's Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources - CAMPFIRE, but has wider implications for the development of sustainable land use practices and resource management regimes in the region. -

Your Phone Number Has Been Updated!

Your phone number has been updated! We have changed your area code, and have updated your phone number. Now you can enjoy the full benefits of a converged network. This directory guides you on the changes to your number. TELONE NUMBER CHANGE UPDATE City/Town Old Area New Area Prefix New number example City/Town Old Area New Area Prefix New number example Code Code Code Code Arcturus 0274 024 214 (024) 214*your number* Lalapanzi 05483 054 2548 (054) 2548*your number* Banket 066 067 214 (067) 214*your number* Lupane 0398 081 2856 (081) 2856*your number* Baobab 0281 081 28 (081)28*your number* Macheke 0379 065 2080 (065) 2080*your number* Battlefields 055 055 25 (055)25*your number* Makuti 063 061 2141 (061) 2141*your number* Beatrice 065 024 2150 (024) 2150*your number* Marondera 0279 065 23 (065) 23*your number* Bindura 0271 066 210 (066) 210*your number* Mashava 035 039 245 (039) 245*your number* Birchenough Bridge 0248 027 203 (027) 203*your number* Masvingo 039 039 2 (039) 2*your number* (029)2*your number* Mataga 0517 039 2366 (039) 2366*your number* Bulawayo 09 029 2 (for numbers with 6 digits) Matopos 0383 029 2809 (039) 2809*your number* (029)22*your number) Bulawayo 09 029 22 Mazowe 0275 066 219 (066) 219*your number* (for numbers with 5 digits) Mberengwa 0518 039 2360 (039)2360*your number* Centenary 057 066 210 (066) 210*your number* Chatsworth 0308 039 2308 (039)2308*your number* Mhangura 060 067 214 (067) 214*your number* Mount Darwin 0276 066 212 (066) 212*your number* Chakari 0688 068 2189 (068) 2189*your number* Murambinda -

IN "CAMPFIRE" Steve J. Thomas. Paper Prepared for the Second

THE LEGACY OP DUALISM AND DECISION —MAKING: THE PROSPECTS FOR LOCAL INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN "CAMPFIRE" Steve J. Thomas. Paper prepared for the Second Annual Conference of the International Association for the Study of Common Property (IASCP) held at University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada. September 26 - 29, 1991. THE LEGACY Of DUALISM AND DECISION—MAKING: the prospects for local institutional development in "CAMPFIRE". Steve J. Thomas. Abstract 'CAMPFIRE' is Zimbabwe's 'Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources'. It seeks to place the management of the wildlife in communal lands into the hands of those communities intimately affected by it. Much of the communal lands is a marginal environment to which the majority of the African population was relocated under divisive legislation introduced by the colonial powers. Parallels are drawn between the colonial and post-colonial periods; the legacy of dualism providing the context within which the prospects for institutional development are discussed. The fugitive nature of the resource suggests the determination of jurisdictional boundaries within which appropriate institutions might function is problematical. Moreover, the 'costs' incurred in 'producing' wildlife must be more than compensated by the benefits accruing from its utilisation. How these benefits are distributed must be decided by 'producer communities' themselves. The success of 'CAMPFIRE' will hinge on the will of central government to decentralise decision-making and control over wildlife resources to local communities, and the willingness and capacity of rural communities to adopt and further this concept of devolution. The legitimacy of the local institutional arrangements which develop will be critical to this success. * Institutional Development Manager with the Zimbabwe Trust, P.O.Box 4027, 4 Lanark Road, Harare, Zimbabwe. -

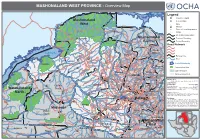

MASHONALAND WEST PROVINCE - Overview Map

MASHONALAND WEST PROVINCE - Overview Map Kanyemba Mana Lake C. Bassa Pools Legend Province Capital Mashonaland Key Location r ive R Mine zi West Hunyani e Paul V Casembi b Chikafa Chidodo Mission Chirundu m Angwa Muzeza a Bridge Z Musengezi Place of Local Importance Rukomechi Masoka Mushumbi Musengezi Mbire Pools Chadereka Village Marongora St. International Boundary Cecelia Makuti Mashonaland Province Boundary Hurungwe Hoya Kaitano Kamuchikukundu Bwazi Chitindiwa Muzarabani District Boundary Shamrocke Bakasa Central St. St. Vuti Alberts Alberts Nembire KARIBA Kachuta Kazunga Chawarura Road Network Charara Lynx Centenary Dotito Kapiri Mwami Guruve Mount Lake Kariba Dora Shinje Masanga Centenary Darwin Doma Mount Maumbe Guruve Gachegache Darwin Railway Line Chalala Tashinga KAROI Kareshi Magunje Bumi Mudindo Bure River Hills Charles Mhangura Nyamhunga Clack Madadzi Goora Mola Mhangura Madombwe Chanetsa Norah Silverside Mutepatepa Bradley Zvipane Chivakanyama Madziwa Lake/Waterbody Kariba Nyakudya Institute Raffingora Jester Mvurwi Vanad Mujere Kapfunde Mudzumu Nzvimbo Shamva Conservation Area Kapfunde Feock Kasimbwi Madziwa Tengwe Siyakobvu Chidamoyo Muswewenhede Chakonda Msapakaruma Chimusimbe Mutorashanga Howard Other Province Negande Chidamoyo Nyota Zave Institute Zvimba Muriel Bindura Siantula Lions Freda & Mashonaland West Den Caesar Rebecca Rukara Mazowe Shamva Marere Shackleton Trojan Shamva Chete CHINHOYI Sutton Amandas Glendale Alaska Alaska BINDURA Banket Muonwe Map Doc Name: Springbok Great Concession Manhenga Tchoda Golden -

ZVIMBA DISTRICT- Natural Farming Regions 14 February 2012

ZVIMBA DISTRICT- Natural Farming Regions 14 February 2012 ra 1 Doma 13 Do Clinic 22 e Chipuriro A m Legend n a 7 zi y Clinic Musenge g n w a 5 a Natural Farming Regions M 8 1 Small Town 22 3 S ami h Chidikamwedzi Mw in Place of local Importance 1 - Specialized and diversified farming e j Clinic 14 t 15 e 4 u CENTENARY 1 k 2A - Intensive farming 5 u 10 28 Mission 7 6 Chikanziwe R Council Clinic Mine 2B - Intensive farming Karoi 10 11 Mupinge M District u 3 - Semi-intensive farming 9 11 i Hospital 8 2 s i Primary School m t w u 4 - Semi-extensive farming 3 Ridziwi v e b u Nyamhondoro Secondary School M Bepura Clinic 5 - Extensive farming Nyangoma Mugarakamwe Clinic 1 Rural Health Council MUDINDO 2 Health Facility Clinic Centre 9 Bare BURE Clinic Province Boundary Mhangura ARDA Sisi Council 12 MHANGURA Private Monera Hospital Clinic District Boundary a e GURUVE w w MADADZI t g i n s M 14 u 6 A Ward Boundary av M a re MHANGURA e 3 m ya Major Road Muitubu an 29 M Clinic Secondary Road 3 13 Feeder Road Donje MADOMBWE NORAH SILVERSIDE Clinic 4 Connector Road Birkdale Track 20 Rural Health HURUNGWE Centre 27 Railway Line 21 Mureche 13 Mukodzongi Clinic River Main River Ranch ire 5 a Chira Clinic r o D NYAKUDYA Nyakudya Kasimube Clinic Rural Health Mvurwi Makope M Raffingora MVURWI 28 Clinic RELATED FARMING SYSTEMS ukwe Centre Rural Hospital JESTER 4 Hospital M 6 u Mvurwi Farm RAFFINGORA s 26 Umboe i Health Scheme Region I - Specialized and Diversified Farming: Rainfall in this region is high (more 16 tw Clinic Ayrshire e Farm Health Clinic a than 1000mm per annum in areas lying below 1700m altitude, and more than 900mm w Council 7 g Clinic per annum at greater altitudes), normally with some precipitation in all months of the n A VANAD year. -

Government Gazette

ZIMBABWEAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority Vol. XCIX, No. 35 12th MARCH, 2021 Price RTGS$155,00 General Notice 296 of 2021. date and must be posted in time to be sorted into Post Office Box ST 14, Southerton, Harare, or delivered by hand to Sally LABOUR ACT [CHAPTER 28:01] Mugabe Central Hospital, Administration Block, before 1000 hours. Application for Registration of an Employers’ Organisation: Tender documents can be inspected and are obtainable from Small to Medium Millers Association of Zimbabwe Sally Mugabe Central Hospital, Procurement Department upon payment of a non-refundable fee of ZWL$800,00, IT is hereby notified, in terms of section 33 of the Labour Act per copy in the Accounts Department. Documents are sold [Chapter 28:01], that an application has been received for the between 1100 hours and 1300 hours during working days registration of Small to Medium Millers Association of Zimbabwe only. as an employers’ organisation to represent the interests of Small and Closing date for tenders is 22nd April, 2021, at 1000 hours. Medium Grain Milling/Processing employers in Zimbabwe. Any person who wishes to make any representations relating to the General Notice 298 of 2021. applicationis invited to lodge such representations with the Registrar NATIONAL BUILDING SOCIETY LIMITED (NBS) of Labour, at Compensation House, at the corner of Simon Vengai Muzenda Street and Ahmed Ben Bella Avenue, Harare, or post them Invitation to Competitive Bidding to Private Bag 7707, Causeway, within 30 days of the publication of this notice and to state whether or not he or she wishes to appear TENDERS are invited from reputable, reliable and well-established in support of such representations at any accreditation proceedings. -

MIDLANDS PROVINCE - Basemap

MIDLANDS PROVINCE - Basemap Mashonaland West Chipango Charara Dunga Kazangarare Charara Hewiyai 8 18 Bvochora 19 9 Ketsanga Gota Lynx Lynx Mtoranhanga Chibara 2 29 Locations A Chitenje 16 21 R I B 4 K A CHARARA 7 Mpofu 23 K E 1 Kachuta 4 L A 12 SAFARI Kapiri DOMA 1 Kemutamba Mwami Kapiri Chingurunguru SAFARI Kosana Guruve AREA Mwami Kapiri Green Matsvitsi Province Capital Mwami Mwami Bakwa AREA Valley 5 Guruve 6 KARIBA 26 Kachiva 1 Doro Shinje Nyaodza Dora Kachiva Shinje Ruyamuro B A R I Masanga Nyamupfukudza 22 Nyama A Nyamupfukudza C e c i l m o u r 22 Town E K Kachekanje Chiwore 18 Nyakapupu K Masanga Doma 2 7 L A Gache- Kachekanje Masanga 23 Lan Doma 3 Gatse Gache lorry 5 Doma Gatse Masanga B l o c k l e y Chipuriro 2 Maumbe Maumbe Rydings GURUVE Bumi 16 Maumbe Hills Gachegache Chikanziwe 8 Kahonde Garangwe Karoi 15 Place of Local Importance Magwizhu Charles Lucky Chalala Tashinga Kareshi Crown 5 Mauya 10 11 Clarke 7 10 3 Mauya Chalala Charles Nyangoma 11 1 Karambanzungu Chitimbe Clarke Magunje 8 Nyamhondoro Hesketh Bepura Chalala Kabvunde KAROI URBAN Mugarakamwe Karambanzungu Magunje Magunje Hesketh Nyangoma Mhangura 9 Kudzanai Army Government Ridziwi Mudindo Nyamhunga Sikona ARDA 9 Mission Nyamhunga Mahororo Charles Chisape HURUNGWE Mhangura Sisi MATUSADONA Murapa Sengwe Dombo Madadzi Nyangoma Mhangura 12 Clack Karoi Katenhe Arda Kanyati Nyamhunga Enterprise Tategura Mhangura NATIONAL 17 Kapare Katenhe Karoi Mine Mhangura Sisi Mola Makande Nyadara Muitubu Mola Nyamhunga 10 Enterprise 14 Mola PARK Makande 11 Mhangura Ramwechete 11 -

Mashonaland West

GOROMONZI WEST Constituency Profile MASHONALAND WEST Goromonzi West is comprised of Makumbe, made impossible by the economic crisis that Mashonaland West is mainly a rural province with a few urban centres. The Zezuru and Korekore Parirewa, Domboshava and Makumbe has deepened. Some areas have been tribes come from this province. Mashonaland West is popular for commercial farms. Before the land Mission. Goromonzi West is one of the new electrified but incessant power cuts have reform programme, the province was the bread basket of Zimbabwe as most of the country's food constituencies that emerged from the splitting disrupted economic activity. The main road is requirements were produced therein. Commercial farms were acquired under the land reform of Goromonzi. The area is near Harare and tarred except for inner roads that are dusty. programme, and the food security of the country has been precarious since then. Zimbabwe has been people in this area find employment in the city. a net importer of food since 2000. The province is home to President Robert Mugabe and province In days gone by, people commuted from REGISTERED VOTERS has voted in favour of ZANU PF in most elections. Goromonzi to work Harare but this has been 27980 SUPPORTING DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS 92 93 SUPPORTING DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS CHINHOYI Constituency Profile Constituency Profile ZVIMBA WEST Chinhoyi constituency is made up of Chinhoyi into A1 and A2 farming models under the Zvimba West comprises Marevanani, Business Centre has small scale home town. Chinhoyi is the provincial capital of government's land reform programme. Mazezuru, Kazangarare, Murombedzi and industries that provide informal employment Mashonaland West province. -

James Murombedzi Centre for Applied Social Sciences, University of Zimbabwe

DECENTRALIZING COMMON PROPERTY RESOURCES MANAGEMENT: A CASE STUDY OF THE NYAMINYAMI DISTRICT COUNCIL OF ZIMBABWE'S WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT PROGRAMME. James Murombedzi Centre for Applied Social Sciences, University of Zimbabwe. Paper prepared for the Common Property Conference, University of Manitoba-Winnipeg, September 26-29, 1991. ABSTRACT This paper focuses on the devolution of the management of Common Property Resources (CPRs) from central government to local communities in the Communal Lands (CLs) of the Zambezi Valley of Zimbabwe. The District Council of these CLs has recently been granted 'appropriate authority' status over the management of the wildlife resources of the CLs. With appropriate authority status, wildlife management programmes have been drawn up and instituted under the Communal Areas Management Programme For Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) and the council is developing local level institutions to manage these resource under common property regimes. This paper outlines the approach taken by the council to devolve control to sub-district levels and draws lessons from this experiences about the problems and prospects of sustainable local management of CPRs. The primary focus is on the dynamics of institutional development and wildlife management under communal tenure regimes. Evidence from the case study seems to suggest that while local; institutions promise to offer solutions to the most pressing problems of common properties, there exists an array of other interests in the commons whose actions and intentions regarding the resource in question present major obstacles to the ability of local communities to evolve effective resource management institutions and strategies. Such interests also tend to be dominant in this dynamic and thus define and determine the process by which management is devolved to the local communities. -

LTC Research Paper

LTC Research Paper Land Tenure, Agrarian Structure, and Comparative Land Use Efficiency in Zimbabwe: Options for Land Tenure Reform and Land Redistribution by Michael R. Roth and John W. Bruce University of Wisconsin-Madison 175A Science Hall 550 North Park Street Madison, WI 53706 http://www.ies.wisc.edu/ltc/ Research Paper LTC Research Paper 117, U.S. ISSN 0084-0815 originally published in 1994 LAND TENURE, AGRARIAN STRUCTURE, AND COMPARATIVE LAND USE EFFICIENCY IN ZIMBABWE: OPTIONS FOR LAND TENURE REFORM AND LAND REDISTRIBUTION by Michael R. Roth and John W. Bruce* * Michael Roth is associate research scientist with the Land Tenure Center and the Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and John Bruce is senior research scientist and Director of the Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA. All views, interpretations, recommendations, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the supporting or cooperating organizations. LTC Research Paper 117 Land Tenure Center University of Wisconsin-Madison August 1994 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables v List of Figures vi List of Acronyms vii Preface vii Chapter 1 Introduction: Land Reform at a Crossroads 1 1.1 Issues 1 1.2 Agrarian structure and resettlement 1 1.3 Land reform policy 2 1.4 Overview of report 4 Chapter 2 Data 5 2.1 Regional disaggregation 5 2.1.1 Provinces 5 2.1.2 Natural regions 8 2.1.3 Spatial overlap 9 2.2 Data sources 10 2.2.1 Census data—large-scale and small-scale commercial -

Kazungula Land Trust Paper.Pmd

Landscape Conservation and Land Tenure in Zambia: Community Trusts in the Kazungula Heartland AWF Working Papers ©Daudi Sumba ©Daudi ©Nyikavanhu Munodawafa ©Nyikavanhu Munodawafa Simon Metcalfe September 2005 The African Wildlife Foundation, together with the people of Africa, works to ensure the wildlife and wild lands of Africa will endure forever. www.awf.org About this paper series The AWF Working Paper Series has been designed to disseminate to partners and the conservation community, aspects of AWF current work from its flagship African Heartlands Program. This series aims to share current work in order not only to share work experiences but also to provoke discussions on whats working or not and how best conservation action can be undertaken to ensure that Africas wildlife and wildlands are conserved forever. About the Author: Simon Metcalfe is the Technical Director for Southern Africa and is based in Harare Zimbabwe The author acknowledges the work done by AWF staff without whom there would be no paper to write: N. Munodawafa; P. Jere; & N. Samu and Daudi Sumba. This paper was edited by an editorial team consisting of Dr. Helen Gichohi, Dr. Philip Muruthi, Prof. James Kiyiapi, Dr. Patrick Bergin, Joanna Elliott and Daudi Sumba. Additional editorial support was provided by Keith Sones. Copyright: This publication is copyrighted to AWF. It may be produced in whole or part and in any form for education and non-profit purposes without any special permission from the copyright holder provided that the source is appropriately acknowledged. This publication should not be used for resale or commecial purposes without prior written permission of AWF.