A FILM by MED HONDO (Mauritania, 1970)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards an Aesthetic of the Migrant Self — the Film Le Clandestin by José Zeka Laplaine

MARIE–HÉLÈNE GUTBERLET ⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯ Towards an Aesthetic of the Migrant Self — The Film Le Clandestin by José Zeka Laplaine A BSTRACT: The representation of migrant arrivals in Europe is at the centre of this investigation of Zeka Laplaine’s short film Le Clandestin (1996). Placing the short film in the context of the African cinematographic traditions of earlier, more conventional, migrant narratives, the essay shows that the associative structure and the postmodern use of irony and magical realism in this short film question both our sense of familiarity and the promise of effortless transcultural communication. 1 OST FILMS (cinema and television productions) dealing with African migration, especially migration to Europe, are produced M and realized by European film and broadcasting companies. They reflect a specific attitude towards individuals and their situation and towards the issue of foreign presence on European soil. The portrayal and production of the African migrant in European media represents a complex field of poli- tically, socially, racially, and aesthetically relevant influences that would need to be analysed specifically. Awareness of these issues has spread beyond the academic field: everybody is more or less familiar with the images of African migrants, with the unease, the exaggerations, humiliations, and transformations taking place in the production of these images, and has learned to view against the grain and sometimes see behind the obvious. Another concern underlies the present essay: are there other ways of expressing and showing the arrival of © Transcultural Modernities: Narrating Africa in Europe, ed. Elisabeth Bekers, Sissy Helff & Daniela Merolla (Matatu 36; Amsterdam & New York NY: Editions Rodopi, 2009). -

The Apology | the B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero Scene & Heard

November-December 2017 VOL. 32 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES N O . 6 IN THIS ISSUE One Week and a Day | Poverty, Inc. | The Apology | The B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero scene & heard BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Learn more about Baker & Taylor’s Scene & Heard team: ELITE Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and customized services to meet continued patron demand PROFICIENT Qualified entertainment content buyers ensure frontlist and backlist titles are available and delivered on time SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music products to your shelf-ready specifications Experience KNOWLEDGEABLE Baker & Taylor is the Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, most experienced in the backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging business; selling A/V expertise products to libraries since 1986. 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review One Week and a Day and target houses that are likely to be empty while mourners are out. Eyal also goes to the HHH1/2 hospice where Ronnie died (and retrieves his Oscilloscope, 98 min., in Hebrew w/English son’s medical marijuana, prompting a later subtitles, not rated, DVD: scene in which he struggles to roll a joint for Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman $34.99, Blu-ray: $39.99 the first time in his life), gets into a conflict Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood Wr i t e r- d i r e c t o r with a taxi driver, and tries (unsuccessfully) to hide in the bushes when his neighbors show Editorial Assistant: Christopher Pitman Asaph Polonsky’s One Week and a Day is a up with a salad. -

French Department Course Brochure 2017-2018

FRENCH DEPARTMENT COURSE BROCHURE 2017-2018 This brochure is also available on our website: http://www.wellesley.edu/french TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Course Descriptions………………………………… 2 – 26 Honors in the French Major (360/370)……..…..…27 – 31 Advanced Placement & Language Requirements, Graduate Study and Teaching………………………32 Requirements for the French Major……….………….33 The French Cultural Studies Major………..…..……..33 Linguistics Course Descriptions…………….……...…34 Maison Française/French House………………….….37 Wellesley-in-Aix……………………………….….……37 Faculty...………………………………………………..38 Awards and Fellowships…………………...……….…41 French Department Sarah Allahverdi ([email protected])….. (781) 283-2403 Hélène Bilis ([email protected]) ….. (781) 283-2413 Venita Datta ([email protected]) ….. (781) 283-2414 On Leave Spring 2018 Sylvaine Egron-Sparrow ([email protected]) ….. (781) 283-2415 French House assistantes….. (781) 283-2413 Marie-Cécile Ganne-Schiermeier ([email protected]) ….. (781) 283-2412 Scott Gunther ([email protected]) ….. (781) 283-2444 Chair-Spring 2018 Andrea Levitt ([email protected]) ….. (781) 283-2410 Barry Lydgate ([email protected]) ….. (781) 283-2439 Catherine Masson ([email protected]) ..….. (781) 283-2417 Codruţa Morari ([email protected]) ….. (781) 283-2479 James Petterson ([email protected]) ….. (781) 283-2423 Anjali Prabhu ([email protected]) ….. (781) 283-2495 Marie-Paule Tranvouez ([email protected]) ….. (781) 283-2975 David Ward ([email protected]) ….. (781) 283-2617 Chair-Fall 2017 Course Distribution, when applicable, is noted in parenthesis following the prerequisites. 1 FRENCH 101-102 (FALL & SPRING) BEGINNING FRENCH I AND II Prerequisite: Open to students who do not present French for admission or by permission of the instructor. French 101-102 is a yearlong course. Students must complete both semesters satisfactorily to receive credit for either course. -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

Martin Scorsese Set to Receive Cinematic Imagery Award from the Art Directors Guild’S Excellence in Production Design Awards, Feb

Martin Scorsese MARTIN SCORSESE SET TO RECEIVE CINEMATIC IMAGERY AWARD FROM THE ART DIRECTORS GUILD’S EXCELLENCE IN PRODUCTION DESIGN AWARDS, FEB. 8, 2014 LOS ANGELES, Dec. 5, 2013 - Academy Award®-winning filmmaker Martin Scorsese, whose films have consistently reflected the highest quality of production design, will receive the prestigious Cinematic Imagery Award from the Art Directors Guild (ADG) at its 18th Annual Art Directors Guild’s Excellence in Production Design Awards, it was announced today by ADG Council Chairman John Shaffner and Awards Producers Raf Lydon and Dave Blass. Set for February 8, 2014, the black-tie ceremony at The Beverly Hilton Hotel will be hosted by Owen Benjamin and will honor more than 40 years of Scorsese’s extraordinary award-winning work. The ADG’s Cinematic Imagery Award is given to those whose body of work in the film industry has richly enhanced the visual aspects of the movie-going experience. Previous recipients have been the Production Designers behind the James Bond franchise, the principal team behind the Harry Potter films, Bill Taylor, Syd Dutton, Warren Beatty, Allen Daviau, Clint Eastwood, Blake Edwards, Terry Gilliam, Ray Harryhausen, Norman Jewison, John Lasseter, George Lucas, Frank Oz, Steven Spielberg, Robert S. Wise and Zhang Yimou. Said Shaffner, "The ADG has wanted Scorsese to accept this deserving honor since the earliest days of its inception. We are beyond delighted that his schedule finally now allows him time to receive it! The ADG has always considered his hands-on pursuit of excellence of production design to equal all of the fine craftsmanship that goes into every aspect of all Martin Scorsese films." Martin Scorsese is one of the most prominent and influential filmmakers working today. -

Wellington Programme

WELLINGTON 24 JULY – 9 AUGUST BOOK AT NZIFF.CO.NZ 44TH WELLINGTON FILM FESTIVAL 2015 Presented by New Zealand Film Festival Trust under the distinguished patronage of His Excellency Lieutenant General The Right Honourable Sir Jerry Mateparae, GNZM, QSO, Governor-General of New Zealand EMBASSY THEATRE PARAMOUNT SOUNDINGS THEATRE, TE PAPA PENTHOUSE CINEMA ROXY CINEMA LIGHT HOUSE PETONE WWW.NZIFF.CO.NZ NGĀ TAONGA SOUND & VISION CITY GALLERY Director: Bill Gosden General Manager: Sharon Byrne Assistant to General Manager: Lisa Bomash Festival Manager: Jenna Udy Publicist (Wellington & Regions): Megan Duffy PROUDLY SUPPORTED BY Publicist (National): Liv Young Programmer: Sandra Reid Assistant Programmer: Michael McDonnell Animation Programmer: Malcolm Turner Children’s Programmer: Nic Marshall Incredibly Strange Programmer: Anthony Timpson Content Manager: Hayden Ellis Materials and Content Assistant: Tom Ainge-Roy Festival Accounts: Alan Collins Publications Manager: Sibilla Paparatti Audience Development Coordinator: Angela Murphy Online Content Coordinator: Kailey Carruthers Guest and Administration Coordinator: Rachael Deller-Pincott Festival Interns: Cianna Canning, Poppy Granger Technical Adviser: Ian Freer Ticketing Supervisor: Amanda Newth Film Handler: Peter Tonks Publication Production: Greg Simpson Publication Design: Ocean Design Group Cover Design: Matt Bluett Cover Illustration: Blair Sayer Animated Title: Anthony Hore (designer), Aaron Hilton (animator), Tim Prebble (sound), Catherine Fitzgerald (producer) THE NEW ZEALAND FILM -

Interview with Med Hondo by Mark Reid and Sylvie Blum

Interview with Med Hondo by Mark Reid and Sylvie Blum http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC31folder/Hon... JUMP CUT A REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA Med Hondo, interview Working abroad by Mark Reid translated from French by Sylvie Blum from Jump Cut, no. 31, March 1986, pp. 48-49 copyright Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, 1986, 2006 The following interview was taped on July 6, 1982, with Med Hondo, actor, director and spokesperson for the African Filmmakers Committee (Comit Africain de Cinastes). The other members of that committee are these: Sembene Ousmane (Senegal), Paulin Vleyra (Senegal), Souleyman Cisse (Mali), J.M. Tchissou Kou (Congo), Karamo Lancine (Ivory Coast), Abacar Samb (Senegal), Daniel Kamusa (Cameroon), Diconque Pipa (Cameroon), Jules Takam (Cameroon), Mustapha Alassan (Niger), Safi Faye (Senegal), Ola Balugun (Nigeria), Film du Ghana, Sidiki Baka (Ivory Coast), Haile Gerima (Ethiopia) and Julie Dash (USA). Med Hondo acted in Costa Gravas's SHOCK TROOPS (1968), Roberto Enrico's ZITA (1968), and John Huston's A WALK WITH LOVE AND DEATH (1969). He has directed the short films BALLADE AUX SOURCES (1967), PARTOUT ET PEUT-ETRE NULLE PART (1968), and MES VOISINS (1971). His feature films are SOLEIL O (1971), BICOTS NEGRES NOS VOISINS (1974), and WEST INDIES (1981). In the U.S., New Yorker Films distributes SOLEIL O. REID: How do you finance your films? HONDO: I financed SOLEIL 0 (1971) with a year and a half's salary dubbing U.S. black voices into French. Ironically, I can't dub white roles yet whites dub black American voices from Hollywood films into French. -

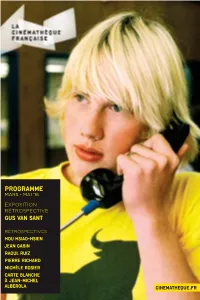

Prog-Web.Pdf

Programme Programme MARS - MAI ‘16 EXPOSITION MARS - MAI 2016 RÉTROSPECTIVE GUS VAN SANT RÉTROSPECTIVES HOU HSIAO-HSIEN Jean gabin Raoul ruiz Pierre richard MichÈle rosier Carte blanche à jean-michel alberola cinematheque.fr La Cinematheque-Parution MDE-012016 19/01/16 15:12 Page1 www.maisondesetatsunis.com POUR Vos voyages à PORTLAND La Maison des Etats-Unis ! Love Portland - 1670 €* Séjour de 7 j. / 5 n. Vols internationaux, hôtel*** Partez assisté d’une équipe de spécialistes qui fera de votre voyage un moment inoubliable. Retrouvez l’ensemble de nos offres www.maisondesetatsunis.com 3, rue Cassette Paris 6ème Tél. 01 53 63 13 43 [email protected] Du lundi au samedi de 10h à 19h. Prix à partir de, soumis à conditions Copyright Torsten Kjellstrand www.travelportland.com Gerry ÉDITORIAL Après Martin Scorsese, c’est à Gus Van Sant que la Cinémathèque française consacre une grande exposition et une rétrospective intégrale. Nourri de modernité euro- péenne, figure du cinéma américain indépendant dans les années 90, à l’instar d’un Jim Jarmush pour la décennie précédente, le cinéaste de Portland, Oregon est un authentique plasticien. Nous sommes heureux de montrer pour la première fois en France ses travaux de photographe et de peintre, et d’établir ainsi des correspon- dances avec ses films. Grand inventeur de dispositifs cinématographiques Elephant( , pour citer le plus connu de ses théorèmes), Gus Van Sant est aussi avide d’expériences commerciales, menées au cœur même de l’industrie (Prête-à-tout, Psychose, Will Hunting ou À la recherche de Forrester), et pour lesquelles il peut déployer toute sa plasticité d’auteur très américain, à la fois modeste et déterminé. -

Ficm Cat16 Todo-01

Contenido Gala Mexicana.......................................................................................................125 estrenos mexicanos.............................................................................126 Homenaje a Consuelo Frank................................................................... 128 Homenaje a Julio Bracho............................................................................136 ............................................................................................................ introducción 4 México Imaginario............................................................................................ 154 ................................................................................................................. Presentación 5 Cine Sin Fronteras.............................................................................................. 165 ..................................................................................... ¡Bienvenidos a Morelia! 6 Programa de Diversidad Sexual...........................................................172 ..................................................... Mensaje de la Secretaría de Cultura 7 Canal 22 Presenta............................................................................................... 178 Mensaje del Instituto Mexicano de Cinematografía ������������9 14° Festival Internacional de Cine de Morelia.............................11 programas especiales........................................................................ 179 -

Putney Swope

THE FILM FOUNDATION 2019 ANNUAL REPORT OVERVIEW The Film Foundation supports the restoration of films from every genre, era, and region, and shares these treasures with audiences through hundreds of screenings every year at festivals, archives, repertory theatres, and other venues around the world. The foundation educates young people with The Story of Movies, its groundbreaking interdisciplinary curriculum that has taught visual literacy to over 10 million US students. In 2019, The Film Foundation welcomed Kathryn Bigelow, Sofia Coppola, Guillermo del Toro, Joanna Hogg, Barry Jenkins, Spike Lee, and Lynne Ramsay to its board of directors. Each has a deep understanding and knowledge of cinema and its history, and is a fierce advocate for its preservation and protection. Preservation and Restoration World Cinema Project Working in partnership with archives and studios, The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project has The Film Foundation has helped save over 850 films restored 40 films from24 countries to date. to date. Completed projects in 2019 included: Completed projects in 2019 included: THE CLOUD– William Wyler’s beloved classic, DODSWORTH; CAPPED STAR (India, 1960, d. Ritwik Ghatak), EL Herbert Kline’s acclaimed documentary about FANTASMA DEL CONVENTO (Mexico, 1934, d. Czechoslovakia during the Nazi occupation, CRISIS: Fernando de Fuentes), LOS OLVIDADOS (Mexico, A FILM OF “THE NAZI WAY”; Arthur Ripley’s film 1950, d. Luis Buñuel), LA FEMME AU COUTEAU noir about a pianist suffering from amnesia, VOICE (Côte d’Ivoire, 1969, d. Timité Bassori), and MUNA IN THE WIND; and John Huston’s 3–strip Technicolor MOTO (Cameroon, 1975, d. Jean–Pierre Dikongué– biography of Toulouse–Lautrec, MOULIN ROUGE. -

Sight & Sound Annual Index 2017

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 27 January to December 2017 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 6:52(r) Amour (2012) 5:17; 6:17 Armano Iannucci Shows, The 11:42 Ask the Dust 2:5 Bakewell, Sarah 9:32 Film review titles are also interview with Koreeda Amours de minuit, Les 9:14 Armisen, Fred 8:38 Asmara, Abigail 11:22 Balaban, Bob 5:54 included and are indicated by Hirokazu 7:8-9 Ampolsk, Alan G. 6:40 Armstrong, Jesse 11:41 Asquith, Anthony 2:9; 5:41, Balasz, Béla 8:40 (r) after the reference; age and cinema Amy 11:38 Army 2:24 46; 10:10, 18, 44 Balch, Antony 2:10 (b) after reference indicates Hotel Salvation 9:8-9, 66(r) An Seohyun 7:32 Army of Shadows, The Assange, Julian Balcon, Michael 2:10; 5:42 a book review Age of Innocence, The (1993) 2:18 Anchors Aweigh 1:25 key sequence showing Risk 8:50-1, 56(r) Balfour, Betty use of abstraction 2:34 Anderson, Adisa 6:42 Melville’s iconicism 9:32, 38 Assassin, The (1961) 3:58 survey of her career A Age of Shadows, The 4:72(r) Anderson, Gillian 3:15 Arnold, Andrea 1:42; 6:8; Assassin, The (2015) 1:44 and films 11:21 Abacus Small Enough to Jail 8:60(r) Agony of Love (1966) 11:19 Anderson, Joseph 11:46 7:51; 9:9; 11:11 Assassination (1964) 2:18 Balin, Mireille 4:52 Abandon Normal Devices Agosto (2014) 5:59 Anderson, Judith 3:35 Arnold, David 1:8 Assassination of the Duke Ball, Wes 3:19 Festival 2017, Castleton 9:7 Ahlberg, Marc 11:19 Anderson, Paul Thomas Aronofsky, Darren 4:57 of Guise, The 7:95 Ballad of Narayama, The Abdi, Barkhad 12:24 Ahmed, Riz 1:53 1:11; 2:30; 4:15 mother! 11:5, 14, 76(r) Assassination of Trotsky, The 1:39 (1958) 11:47 Abel, Tom 12:9 Ahwesh, Peggy 12:19 Anderson, Paul W.S. -

B Fi S O Uth Ba

w MUSICALS! THE GREATEST SHOW ON SCREEN MED HONDO MAURICE PIALAT FESTIVE FAVOURITES THE UMBRELLAS OF CHERBOURG SOUTHBANK BFI DEC 2019 THE NURI BILGE CEYLAN BLU-RAY BOX SET By any reckoning Nuri Bilge Ceylan is one of the world’s foremost filmmakers. The box set contains all 8 of his feature films to date, an early short, Koza, plus interviews and behind the scenes documentaries. Kasaba, Clouds of May, Uzak, Climates and Three Monkeys are all appearing on Blu-ray for the first time. The discs of Kasaba, Clouds of May, Uzak and Climates are region-free. The others are region B. RELEASE DATE 28TH OCTOBER www.newwavefilms.co.uk Nuri Bilge Ceylan BFI ad.indd 1 01/10/2019 15:00 THIS MONTH AT BFI SOUTHBANK THE NURI BILGE CEYLAN BLU-RAY BOX SET Welcome to the home of great film and TV, with a world-class library, free exhibitions and Mediatheque and plenty of food and drink By any reckoning Nuri Bilge Ceylan is one IN PERSON & PREVIEWS RE-RELEASES SEASONS Talent Q&As and rare appearances, plus a chance Key classics (many newly restored) for you to enjoy, with plenty of Carefully curated collections of film of the world’s foremost filmmakers. for you to catch the latest film and TV before screening dates to choose from and TV, which showcase an influential anyone else genre, theme or talent The box set contains all 8 of his feature films to date, an early short, Koza, (p34) plus interviews and behind the scenes (p13) documentaries. (p7) Kasaba, Clouds of May, Uzak, Climates and Three Monkeys are all appearing on Blu-ray for the first time.