H. MARINHO CARVALHO Phd July 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index (Complete)

Sample page from Pianos Inside Out. Copyright © 2013 Mario Igrec. 527 Index composite parts 375 rails, repairing 240 facing off 439 Numerics compressed 68 rebuilding, overview 325 grooved, effects on tuning 132 105 System 336 diagram 64 regulating 166 reducing height of 439 16th Tone Piano 94 Double Repetition in verticals 77 regulating on the bench 141 replacing 436 1867 Exposition in Paris 13 double-escapement 5, 12 regulation, effects on tuning 129 to rebuild or replace 326 3M 267, 338 dropped 68, 113, 140, 320 removing 136 Air microfinishing film 202 English 9 removing from keyboard 154 dehumidifying 85 409 89 escapement of jack 76 repairing 240 humidifying 86 Fandrich 68 repetition, speed of 77 Air conditioner 86, 328 frame stability in verticals, Schwander 77 Albert Steinway 13, 76 A inspecting 191 single-escapement 4 Alcohol 144, 145, 147, 155, 156, 158, Abel 66, 71, 72, 340, 383 geometry 273, 303 spread 149, 280, 282, 287, 315 161, 179, 182, 191, 213, 217, 221, hammers 72, 384 geometry troubleshooter 304 tape-check 11 237, 238, 264, 265, 337, 338, 352, Naturals 71 grand, inserting into the piano troubleshooters 304 353, 356, 437, 439, 449, 478 Abrasive cord 338 137 Tubular Metallic Frame 66, 68 as sizing agent 215, 491 Abrasives, in buffing compounds grand, rebuilding 373 vertical 68 as solvent for shellac 480 364 grand, regulating 166 vertical, development of 15 as suspension for blue chalk 449 ABS grand, removing 136 vertical, Double Repetition 77 as suspension for chalk 240, 364, Carbon 17, 66 grand, removing from keyboard vertical, -

1785-1998 September 1998

THE EVOLUTION OF THE BROADWOOD GRAND PIANO 1785-1998 by Alastair Laurence DPhil. University of York Department of Music September 1998 Broadwood Grand Piano of 1801 (Finchcocks Collection, Goudhurst, Kent) Abstract: The Evolution of the Broadwood Grand Piano, 1785-1998 This dissertation describes the way in which one company's product - the grand piano - evolved over a period of two hundred and thirteen years. The account begins by tracing the origins of the English grand, then proceeds with a description of the earliest surviving models by Broadwood, dating from the late eighteenth century. Next follows an examination of John Broadwood and Sons' piano production methods in London during the early nineteenth century, and the transition from small-scale workshop to large factory is noted. The dissertation then proceeds to record in detail the many small changes to grand design which took place as the nineteenth century progressed, ranging from the extension of the keyboard compass, to the introduction of novel technical features such as the famous Broadwood barless steel frame. The dissertation concludes by charting the survival of the Broadwood grand piano since 1914, and records the numerous difficulties which have faced the long-established company during the present century. The unique feature of this dissertation is the way in which much of the information it contains has been collected as a result of the writer's own practical involvement in piano making, tuning and restoring over a period of thirty years; he has had the opportunity to examine many different kinds of Broadwood grand from a variety of historical periods. -

Pedal in Liszt's Piano Music!

! Abstract! The purpose of this study is to discuss the problems that occur when some of Franz Liszt’s original pedal markings are realized on the modern piano. Both the construction and sound of the piano have developed since Liszt’s time. Some of Liszt’s curious long pedal indications produce an interesting sound effect on instruments built in his time. When these pedal markings are realized on modern pianos the sound is not as clear as on a Liszt-time piano and in some cases it is difficult to recognize all the tones in a passage that includes these pedal markings. The precondition of this study is the respectful following of the pedal indications as scored by the composer. Therefore, the study tries to find means of interpretation (excluding the more frequent change of the pedal), which would help to achieve a clearer sound with the !effects of the long pedal on a modern piano.! This study considers the factors that create the difference between the sound quality of Liszt-time and modern instruments. Single tones in different registers have been recorded on both pianos for that purpose. The sound signals from the two pianos have been presented in graphic form and an attempt has been made to pinpoint the dissimilarities. In addition, some examples of the long pedal desired by Liszt have been recorded and the sound signals of these examples have been analyzed. The study also deals with certain aspects of the impact of texture and register on the clarity of sound in the case of the long pedal. -

VIVACE AUTUMN / WINTER 2016 Photo © Martin Kubica Photo

VIVACEAUTUMN / WINTER 2016 Classical music review in Supraphon recordings Photo archive PPC archive Photo Photo © Jan Houda Photo LUKÁŠ VASILEK SIMONA ŠATUROVÁ TOMÁŠ NETOPIL Borggreve © Marco Photo Photo © David Konečný Photo Photo © Petr Kurečka © Petr Photo MARKO IVANOVIĆ RADEK BABORÁK RICHARD NOVÁK CP archive Photo Photo © Lukáš Kadeřábek Photo JANA SEMERÁDOVÁ • MAREK ŠTRYNCL • ROMAN VÁLEK Photo © Martin Kubica Photo XENIA LÖFFLER 1 VIVACE AUTUMN / WINTER 2016 Photo © Martin Kubica Photo Dear friends, of Kabeláč, the second greatest 20th-century Czech symphonist, only When looking over the fruits of Supraphon’s autumn harvest, I can eclipsed by Martinů. The project represents the first large repayment observe that a number of them have a common denominator, one per- to the man, whose upright posture and unyielding nature made him taining to the autumn of life, maturity and reflections on life-long “inconvenient” during World War II and the Communist regime work. I would thus like to highlight a few of our albums, viewed from alike, a human who remained faithful to his principles even when it this very angle of vision. resulted in his works not being allowed to be performed, paying the This year, we have paid special attention to Bohuslav Martinů in price of existential uncertainty and imperilment. particular. Tomáš Netopil deserves merit for an exquisite and highly A totally different hindsight is afforded by the unique album acclaimed recording (the Sunday Times Album of the Week, for of J. S. Bach’s complete Brandenburg Concertos, which has been instance), featuring one of the composer’s final two operas, Ariane, released on CD for the very first time. -

Mozart's Piano

MOZART’S PIANO Program Notes by Charlotte Nediger J.C. BACH SYMPHONY IN G MINOR, OP. 6, NO. 6 Of Johann Sebastian Bach’s many children, four enjoyed substantial careers as musicians: Carl Philipp Emanuel and Wilhelm Friedemann, born in Weimar to Maria Barbara; and Johann Christoph Friedrich and Johann Christian, born some twenty years later in Leipzig to Anna Magdalena. The youngest son, Johann Christian, is often called “the London Bach.” He was by far the most travelled member of the Bach family. After his father’s death in 1750, the fifteen-year-old went to Berlin to live and study with his brother Emanuel. A fascination with Italian opera led him to Italy four years later. He held posts in various centres in Italy (even converting to Catholicism) before settling in London in 1762. There he enjoyed considerable success as an opera composer, but left a greater mark by organizing an enormously successful concert series with his compatriot Carl Friedrich Abel. Much of the music at these concerts, which included cantatas, symphonies, sonatas, and concertos, was written by Bach and Abel themselves. Johann Christian is regarded today as one of the chief masters of the galant style, writing music that is elegant and vivacious, but the rather dark and dramatic Symphony in G Minor, op. 6, no. 6 reveals a more passionate aspect of his work. J.C. Bach is often cited as the single most important external influence on Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Mozart synthesized the wide range of music he encountered as a child, but the one influence that stands out is that of J.C. -

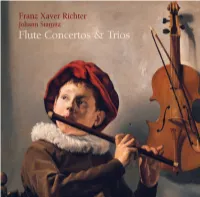

Booklet & CD Design & Typography: David Tayler Cover Art: Adriaen Coorte

Voices of Music An Evening with Bach An Evening with Bach 1. Air on a G string (BWV 1069) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) 2. Schlummert ein (BWV 82) Susanne Rydén, soprano 3. Badinerie (BWV 1067) Dan Laurin, voice flute 4. Ich folge dir gleichfalls (St. John Passion BWV 245) Susanne Rydén, soprano; Louise Carslake, baroque flute 5. Giga (BWV 1004) Dan Laurin, recorder 6. Schafe können sicher weiden (BWV 208) Susanne Rydén, soprano 7. Prelude in C minor (BWV 871) Hanneke van Proosdij, harpsichord 8. Schlafe mein Liebster (BWV 213) Susanne Rydén, soprano 9. Prelude in G major (BWV 1007) David Tayler, theorbo 10. Es ist vollbracht (St. John Passion BWV 245) Jennifer Lane, alto; William Skeen, viola da gamba 11. Sarabanda (BWV 1004) Elizabeth Blumenstock, baroque violin 12. Kein Arzt ist außer dir zu finden (BWV 103) Jennifer Lane, alto; Hanneke van Proosdij, sixth flute 13. Prelude in E flat major (BWV 998) Hanneke van Proosdij, lautenwerk 14. Bist du bei mir (BWV 508) Susanne Rydén, soprano 15. Passacaglia Mein Freund ist mein J.C. Bach (1642–1703) Susanne Rydén, soprano; Elizabeth Blumenstock, baroque violin Notes The Great Collectors During the 1980s, both Classical & Early Music recordings underwent a profound change due to the advent of the Compact Disc as well as the arrival of larger stores specializing in music. One of the casualties of this change was the recital recording, in which an artist or ensemble would present an interesting arrangement of musical pieces that followed a certain theme or style—much like a live concert. Although recital recordings were of course made, and are perhaps making a comeback, most recordings featured a single composer and were sold in alphabetized bins: B for Bach; V for Vivaldi. -

Akademie Für Alte Musik Berlin

UMS PRESENTS AKADEMIE FÜR ALTE MUSIK BERLIN Sunday Afternoon, April 13, 2014 at 4:00 Hill Auditorium • Ann Arbor 66th Performance of the 135th Annual Season 135th Annual Choral Union Series Photo: Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin; photographer: Kristof Fischer. 31 UMS PROGRAM Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 1 in C Major, BWV 1066 Ouverture Courante Gavotte I, II Forlane Menuett I, II Bourrée I, II Passepied I, II Johann Christian Bach (previously attributed to Wilhelm Friedmann Bach) Concerto for Harpsichord, Strings, and Basso Continuo in f minor Allegro di molto Andante Prestissimo Raphael Alpermann, Harpsichord Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach WINTER 2014 Symphony No. 5 for Strings and Basso Continuo in b minor, Wq. 182, H. 661 Allegretto Larghetto Presto INTERMISSION AKADEMIE FÜR ALTE MUSIK BERLIN AKADEMIE FÜR ALTE 32 BE PRESENT C.P.E. Bach Concerto for Oboe, Strings, and Basso Continuo in E-flat Major, Wq. 165, H. 468 Allegro Adagio ma non troppo Allegro ma non troppo Xenia Löeffler,Oboe J.C. Bach Symphony in g minor for Strings, Two Oboes, Two Horns, and Basso Continuo, Op. 6, No. 6 Allegro Andante più tosto adagio Allegro molto WINTER 2014 Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM. Special thanks to Tom Thompson of Tom Thompson Flowers, Ann Arbor, for his generous contribution of floral art for this evening’s concert. Special thanks to Kipp Cortez for coordinating the pre-concert music on the Charles Baird Carillon. This tour is made possible by the generous support of the Goethe Institut and the Auswärtige Amt (Federal Foreign Office). -

Download Booklet

Classics Contemporaries of Mozart Collection COMPACT DISC ONE Franz Krommer (1759–1831) Symphony in D major, Op. 40* 28:03 1 I Adagio – Allegro vivace 9:27 2 II Adagio 7:23 3 III Allegretto 4:46 4 IV Allegro 6:22 Symphony in C minor, Op. 102* 29:26 5 I Largo – Allegro vivace 5:28 6 II Adagio 7:10 7 III Allegretto 7:03 8 IV Allegro 6:32 TT 57:38 COMPACT DISC TWO Carl Philipp Stamitz (1745–1801) Symphony in F major, Op. 24 No. 3 (F 5) 14:47 1 I Grave – Allegro assai 6:16 2 II Andante moderato – 4:05 3 III Allegretto/Allegro assai 4:23 Matthias Bamert 3 Symphony in G major, Op. 68 (B 156) 24:19 Symphony in C major, Op. 13/16 No. 5 (C 5) 16:33 5 I Allegro vivace assai 7:02 4 I Grave – Allegro assai 5:49 6 II Adagio 7:24 5 II Andante grazioso 6:07 7 III Menuetto e Trio 3:43 6 III Allegro 4:31 8 IV Rondo. Allegro 6:03 Symphony in G major, Op. 13/16 No. 4 (G 5) 13:35 Symphony in D minor (B 147) 22:45 7 I Presto 4:16 9 I Maestoso – Allegro con spirito quasi presto 8:21 8 II Andantino 5:15 10 II Adagio 4:40 9 III Prestissimo 3:58 11 III Menuetto e Trio. Allegretto 5:21 12 IV Rondo. Allegro 4:18 Symphony in D major ‘La Chasse’ (D 10) 16:19 TT 70:27 10 I Grave – Allegro 4:05 11 II Andante 6:04 12 III Allegro moderato – Presto 6:04 COMPACT DISC FOUR TT 61:35 Leopold Kozeluch (1747 –1818) 18:08 COMPACT DISC THREE Symphony in D major 1 I Adagio – Allegro 5:13 Ignace Joseph Pleyel (1757 – 1831) 2 II Poco adagio 5:07 3 III Menuetto e Trio. -

The Family Bach November 2016

Music of the Baroque Chorus and Orchestra Jane Glover, Music Director Violin 1 Flute Gina DiBello, Mary Stolper, principal concertmaster Alyce Johnson Kevin Case, assistant Oboe concertmaster Jennet Ingle, principal Kathleen Brauer, Peggy Michel assistant concertmaster Bassoon Teresa Fream William Buchman, Michael Shelton principal Paul Vanderwerf Horn Violin 2 Samuel Hamzem, Sharon Polifrone, principal principal Fritz Foss Ann Palen Rika Seko Harpsichord Paul Zafer Stephen Alltop François Henkins Viola Elizabeth Hagen, principal Terri Van Valkinburgh Claudia Lasareff- Mironoff Benton Wedge Cello Barbara Haffner, principal Judy Stone Mark Brandfonbrener Bass Collins Trier, principal Andrew Anderson Performing parts based on the critical edition Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: The Complete Works (www.cpebach.org) were made available by the publisher, the Packard Humanities Institute of Los Altos, California. The Family Bach Jane Glover, conductor Sunday, November 20, 2016, 7:30 PM North Shore Center for the Performing Arts, Skokie Tuesday, November 22, 2016, 7:30 PM Harris Theater for Music and Dance, Chicago Gina DiBello, violin Mary Stolper, flute Sinfonia from Cantata No. 42 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Adagio and Fugue for 2 Flutes Wilhelm Friedemann Bach and Strings in D Minor (1710-1784) Adagio Allegro Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major J. S. Bach Allegro Adagio Allegro assai Gina DiBello, violin INTERMISSION Flute Concerto in B-flat Major Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788) Allegretto Adagio Allegro assai Mary Stolper, flute Symphony in G Minor, op. 6, no. 6 Johann Christian Bach (1735-1782) Allegro Andante più tosto Adagio Allegro molto Biographies Acclaimed British conductor Jane Glover has been Music of the Baroque’s music director since 2002. -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J. -

UCL CMC Newsletter No.5

UCL Chamber Music Club Newsletter No.5 October 2015 In this issue: Welcome to our newsletter Welcome to the fifth issue of the Chamber Mu- Cohorts of muses, sic Club Newsletter and its third year of pub- unaccompanied lication. We offer a variety of articles, from a composers and large survey of last season’s CMC concerts – now a ensembles – a view on the regular feature – to some reflections, informed sixty-third season - by both personal experience and scholarship, page 2 on the music of Sibelius and Nielsen (whose 150th anniversaries are celebrated in the first UCLU Music Society concert of our new season). In the wake of UC- concerts this term - Opera’s production last March of J.C. Bach’s page 8 Amadis de Gaule we have a brief review and two articles outlining the composer’s biogra- UCOpera’s production of phy and putting him in a wider context. The Amadis de Gaule, CMC concert last February based on ‘the fig- UCL Bloomsbury Theatre, ure 8’ has prompted an article discussing some 23-28 March 2015 - aspects of the topic ‘music and numbers’. Not page 9 least, our ‘meet the committee’ series continues with an interview with one of our newest and Meet the committee – youngest committee members, Jamie Parkin- Jamie Parkinson - son. page 9 We hope you enjoy reading the newslet- A biographical sketch of ter. We also hope that more of our readers Johann Christian Bach will become our writers! Our sixth issue is (1735-82): composer, scheduled for February 2016, and any material impresario, keyboard on musical matters – full-length articles (max- player and freemason - imum 3000 words), book or concert reviews – page 12 will be welcome. -

7619990104068.Pdf

Franz Xaver Richter Johann Stamitz Flute Concertos & Trios Jana Semerádová transverse flute Ensemble Castor Petra Samhaber-Eckhardt, Recording: 14-16 February 2019, Landesmusikschule, Ried (Austria) Monika Toth violin Recording producer, digital editing & mastering: Uwe Walter Executive producer: Michael Sawall Peter Aigner viola Layout & booklet editor: Joachim Berenbold Translation: Katie Stephens (English) Peter Trefflinger violoncello Cover picture: “Boy playing the flute“, Judith Leyster (early 1630s), Nationalmuseum Stockholm Barbara Fischer violone + © 2019 note 1 music gmbh, Heidelberg, Germany CD manufactured in The Netherlands Erich Traxler harpsichord Franz Xaver Richter (1709-1789) Franz Xaver Richter Flute Concerto in E minor Harpsichord Trio in D major for transverse flute, strings & b.c. for obbligato harpsichord, violin & cello 1 Allegro moderato 9:09 10 Allegretto 7:18 2 Andantino 7:33 11 Larghetto 6:49 3 Allegro, ma non troppo 4:15 12 Presto, ma non troppo 3:00 Trio Sonata Op. 4 No. 1 in B flat major Harpsichord Trio in G minor for 2 violins & b.c. for obbligato harpsichord, violin & cello 4 Allegro brillante 3:25 13 Andante 7:37 5 Poco andante gracioso 5:23 14 Larghetto - Un poco andante 4:39 6 Allegro 2:39 15 Allegro, ma non troppo 3:02 Johann Stamitz (1717-1757) Flute Concerto in G major for transverse flute, strings & b.c. 7 Allegro moderato 6:07 8 Adagio 4:53 9 Presto 4:01 Was haben die Medici, die gleichsam wohlha- ein beträchtliches Vermögen verfügen konnte. erkannte Karl Theodor das repräsentative Einer der Vorreiter des neuen musikalischen bende und einflussreiche Bankiersfamilie aus Einer Überlieferung zufolge soll Anna Maria Potential der Instrumentalmusik.