The Family Bach November 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Two Flutes

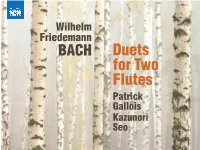

Wilhelm Friedemann BACH Duets for Two Flutes Patrick Gallois Kazunori Seo Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1710–1784) Sonatas has been the object of some speculation.1 It has two-part writing, its rapid outer movements framing a C Six Duets for Two Flutes, F.54–59 been suggested that the Duets in E minor, F.54 and G major, minor Adagio. The Duet in F major, F.57, has at its heart a F.59 may be relatively early works, dating from 1729 or D minor Cantabile, the two parts intricately interwoven, with Born in Weimar in 1710, Wilhelm Friedemann Bach was the Sebastian had abandoned what had been, until his patron’s perhaps from his first years in Dresden. The Duets in E flat a rapid final movement. The demands for virtuosity suggest eldest son of Johann Sebastian Bach by his first wife, Maria marriage, a happy position at court for employment under major, F.55 and F major, F.57 may have been written before the influence of distinguished flautists in Dresden, Pierre- Barbara. When his father moved to Cöthen in 1717 as Court the city council in Leipzig, so his son left the court society of 1741, a date suggested by the use made of extracts for his Gabriel Buffardin, the teacher of Quantz, who was employed Kapellmeister to the young Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen, Dresden for municipal employment in Halle, the birth-place Solfeggi by Quantz, who was then employed by Frederick for many years at the court of the Elector of Saxony and, Wilhelm Friedemann presumably studied at the Lutheran of Handel, who had briefly served as organist there. -

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach COMPLETE ORGAN MUSIC Filippo Turri Wilhelm Friedemann Bach 1710-1784 The first son of Johann Sebastian and Maria Barbara Bach, Wilhelm Friedemann Complete Organ Music Bach (Weimar, 22 November 1710 – Berlin, 1 July 1784) lived a life that in many respects would fit in perfectly with the biography of a tormented artist of the Drei dreistimmigen Fugen Sieben Choralvorspiele F.38 romantic age. He studied under his father, showing early talent as an instrumentalist Three 3-part Fugues Seven Chorale Preludes F.38 (organist, harpsichordist, violinist) and composer, as well as considerable gifts as 1. Fugue in B flat F.34 2’56 15. I. Nun komm der a mathematician. Given his father’s Pythagorean passions, this latter aptitude is 2. Fugue in F F.33 5’22 Heiden Heiland 1’46 not really as surprising at it might at first seem, yet it is certainly true that Wilhelm 3. Fugue in C minor F.32 6’38 16. II. Christe, der du bist Tag Friedemann was versatile and his interests widespread. At the early age of 23 he was und Licht 2’15 appointed principal organist at the church of St. Sophia in Dresden, and in 1747 Acht dreistimmigen Fugen für Orgel 17. III. Jesu, meine Freude 3’59 became Musikdirektor and organist at the Church of Our Lady in Halle. On account oder Clavier F.31 18. IV. Durch Adams Fall is of his years in Halle, where he married Dorothea Elisabeth Georgi (1721-1791), he is Eight 3-part fugues for Organ ganz verderbt 3’35 often referred to as the “Halle” Bach. -

Mozart's Piano

MOZART’S PIANO Program Notes by Charlotte Nediger J.C. BACH SYMPHONY IN G MINOR, OP. 6, NO. 6 Of Johann Sebastian Bach’s many children, four enjoyed substantial careers as musicians: Carl Philipp Emanuel and Wilhelm Friedemann, born in Weimar to Maria Barbara; and Johann Christoph Friedrich and Johann Christian, born some twenty years later in Leipzig to Anna Magdalena. The youngest son, Johann Christian, is often called “the London Bach.” He was by far the most travelled member of the Bach family. After his father’s death in 1750, the fifteen-year-old went to Berlin to live and study with his brother Emanuel. A fascination with Italian opera led him to Italy four years later. He held posts in various centres in Italy (even converting to Catholicism) before settling in London in 1762. There he enjoyed considerable success as an opera composer, but left a greater mark by organizing an enormously successful concert series with his compatriot Carl Friedrich Abel. Much of the music at these concerts, which included cantatas, symphonies, sonatas, and concertos, was written by Bach and Abel themselves. Johann Christian is regarded today as one of the chief masters of the galant style, writing music that is elegant and vivacious, but the rather dark and dramatic Symphony in G Minor, op. 6, no. 6 reveals a more passionate aspect of his work. J.C. Bach is often cited as the single most important external influence on Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Mozart synthesized the wide range of music he encountered as a child, but the one influence that stands out is that of J.C. -

Akademie Für Alte Musik Berlin

UMS PRESENTS AKADEMIE FÜR ALTE MUSIK BERLIN Sunday Afternoon, April 13, 2014 at 4:00 Hill Auditorium • Ann Arbor 66th Performance of the 135th Annual Season 135th Annual Choral Union Series Photo: Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin; photographer: Kristof Fischer. 31 UMS PROGRAM Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 1 in C Major, BWV 1066 Ouverture Courante Gavotte I, II Forlane Menuett I, II Bourrée I, II Passepied I, II Johann Christian Bach (previously attributed to Wilhelm Friedmann Bach) Concerto for Harpsichord, Strings, and Basso Continuo in f minor Allegro di molto Andante Prestissimo Raphael Alpermann, Harpsichord Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach WINTER 2014 Symphony No. 5 for Strings and Basso Continuo in b minor, Wq. 182, H. 661 Allegretto Larghetto Presto INTERMISSION AKADEMIE FÜR ALTE MUSIK BERLIN AKADEMIE FÜR ALTE 32 BE PRESENT C.P.E. Bach Concerto for Oboe, Strings, and Basso Continuo in E-flat Major, Wq. 165, H. 468 Allegro Adagio ma non troppo Allegro ma non troppo Xenia Löeffler,Oboe J.C. Bach Symphony in g minor for Strings, Two Oboes, Two Horns, and Basso Continuo, Op. 6, No. 6 Allegro Andante più tosto adagio Allegro molto WINTER 2014 Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM. Special thanks to Tom Thompson of Tom Thompson Flowers, Ann Arbor, for his generous contribution of floral art for this evening’s concert. Special thanks to Kipp Cortez for coordinating the pre-concert music on the Charles Baird Carillon. This tour is made possible by the generous support of the Goethe Institut and the Auswärtige Amt (Federal Foreign Office). -

Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis

Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis All BWV (All data), numerical order Print: 25 January, 1997 To be BWV Title Subtitle & Notes Strength placed after 1 Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern Kantate am Fest Mariae Verkündigung (Festo annuntiationis Soli: S, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Corno I, II; Ob. da Mariae) caccia I, II; Viol. conc. I, II; Viol. rip. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 2 Ach Gott, von Himmel sieh darein Kantate am zweiten Sonntag nach Trinitatis (Dominica 2 post Soli: A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Tromb. I - IV; Ob. I, II; Trinitatis) Viol. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 3 Ach Gott, wie manches Herzeleid Kantate am zweiten Sonntag nach Epiphanias (Dominica 2 Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Corno; Tromb.; Ob. post Epiphanias) d'amore I, II; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 4 Christ lag in Todes Banden Kantate am Osterfest (Feria Paschatos) Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Cornetto; Tromb. I, II, III; Viol. I, II; Vla. I, II; Cont. 5 Wo soll ich fliehen hin Kantate am 19. Sonntag nach Trinitatis (Dominica 19 post Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Tromba da tirarsi; Trinitatis) Ob. I, II; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Vcl. (Vcl. picc.?); Cont. 6 Bleib bei uns, denn es will Abend werden Kantate am zweiten Osterfesttag (Feria 2 Paschatos) Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Ob. I, II; Ob. da caccia; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Vcl. picc. (Viola pomposa); Cont. 7 Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam Kantate am Fest Johannis des Taüfers (Festo S. -

Jane Glover Conductor

13 Ardilaun Road London N5 2QR Tel: 020 7359 5183 Fax: 020 7226 9792 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.musicint.co.uk JANE GLOVER CONDUCTOR Jane Glover studied at the University of Oxford, where, after graduation, she did her D.Phil. on 17th-century Venetian opera. She holds honorary degrees from several other universities, a personal Professorship at the University of London, and is a Fellow of the Royal College of Music. She joined Glyndebourne in 1979, becoming Music Director of Glyndebourne Touring Opera from 1981 to 1985 and Artistic Director of the London Mozart Players from 1984 to 1991. From 1990 to 1995 she served on the Board of Governors of the BBC and was created a CBE in the 2003 New Year’s Honours. She is Director of Opera at the Royal Academy of Music, London, and is also Music Director of Chicago’s Music of the Baroque. Jane Glover has appeared with the Royal Opera, Covent Garden, English National Opera, Glyndebourne and Wexford Festivals, Metropolitan Opera, Berlin Staatsoper, Royal Danish Opera, Opéra National du Rhin, Teatro Real, Madrid, Opéra National de Bordeaux, Teatro La Fenice, Glimmerglass Opera, New York City Opera, Opera Australia, Opera Theatre of St. Louis, Chicago Opera Theater, Luminato, Toronto and Aspen Festivals. Particularly known as a Mozart specialist, her core repertoire also includes Monteverdi, Handel and Britten, who indeed personally influenced and guided her when she was 16, and to whose music she constantly returns. She has performed with all the major symphony and chamber orchestras in Britain, at the BBC Proms as well as with orchestras in Europe, the US, the Far East and Australasia including the Orchestra of St Luke’s, Philadelphia Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, Houston Symphony, St Louis Symphony, Cincinnati Symphony, Toronto Symphony, Sydney Symphony, Belgrade Philharmonic and Orchestre Nationale de Bordeaux et Aquitaine. -

Rethinking J.S. Bach's Musical Offering

Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Anatoly Milka All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3706-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3706-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... vii List of Schemes ....................................................................................... viii List of Music Examples .............................................................................. x List of Tables ............................................................................................ xii List of Abbreviations ............................................................................... xiii Preface ...................................................................................................... xv Introduction ............................................................................................... -

Margaret Catchpole: Two Worlds Apart

Stephen DODGSON Margaret Catchpole: Two Worlds Apart (Chamber opera in four acts) Howden • Wallace • Morris • Ollerenshaw Edgar-Wilson • Brook • Moore • Willcock • Sporsén Perpetuo • Julian Perkins Stephen Act I: By the Banks of the Orwell Act II: The Cobbold Household 1 [Introduction] 2:27 Scene 1: The drawing room at Mrs Cobbold’s house DO(1D924G–20S13O) N ^ 2Scene 1: Harvest time at Priory Farm & You are young (Dr Stebbing) 4:25 3 What an almighty fuss (Luff, Laud) 1:35 Ah! Dr Stebbing and Mr Barry Margaret Catchpole: Two Worlds Apart 4 For so many years (Laud, Luff) 2:09 (Mrs Cobbold, Barry, Margaret) 6:54 Chamber opera in four acts (1979) 5 Oh harvest moon (Margaret, Laud) 5:26 * Under that far and shining sky Interlude to Scene 2 1:28 Libretto by Ronald Fletcher (1921–1992), 6 (Laud, Margaret) 1:35 based on the novel by Richard Cobbold (1797–1877) The harvest is ended Scene 2: Porch – Kitchen/parlour – First performance: 8–10 June 1979 at The Old School, Hadleigh, Suffolk, UK 7 (Denton, Margaret, Laud, Labourers) 2:19 (Drawing room Oh, my goodness gracious – look! I don’t care what you think Margaret Catchpole . Kate Howden, Mezzo-soprano 8 (Mrs Denton, Lucy, Margaret, Denton) 2:23 ) (Alice, Margaret) 2:26 Will Laud . William Wallace, Tenor 9 Margaret? (Barry, Margaret) 3:39 Come in, Margaret John Luff . Nicholas Morris, Bass The ripen’d corn in sheaves is born ¡ (Mrs Cobbold, Margaret) 6:30 (Second Labourer, Denton, First Labourer, John Barry . Alistair Ollerenshaw, Baritone Come then, Alice (Margaret, Alice, Laud) 8:46 0 Mrs Denton, Lucy, Barry) 5:10 ™ Crusoe . -

Verlorene Kirchen Dresdens Zerstörte Gotteshäuser Eine Dokumentation Seit 1938

Faktum Dresden Die sächsische Landeshauptstadt in Zahlen · 2015/2016 Verlorene Kirchen Dresdens zerstörte Gotteshäuser Eine Dokumentation seit 1938 Verlorene Kirchen Dresdens zerstörte Gotteshäuser Eine Dokumentation seit 1938 Dank Abb. 1: Rathaus und Evangelisch-reformierte Kirche, um 1910 Für umfangreiche Unterstützung oder für die Bereitstellung historischer Unterlagen danken die Autoren ■ Dr. Roland Ander ■ Eberhard Mittelbach, ehemaliger ■ Claudia Baum Sprengmeister ■ Pfarrer i. R. Johannes Böhme ■ Anita Niederlag, Landesamt für Denk- ■ Ulrich Eichler malpflege ■ Pfarrer Bernd Fischer, St.-Franziskus- ■ Rosemarie Petzold Xaverius-Gemeinde ■ Gerd Pfitzner, Amt für Kultur und ■ Martina Fröhlich, Bildstelle Stadt- Denkmalschutz planungsamt ■ Pfarrer i. R. Hanno Schmidt ■ Gerd Hiltscher, ehemaliger Küster der ■ Pfarrer Michael Schubert, St.-Pauli- Versöhnungskirche Gemeinde ■ Uwe Kind, Ipro Dresden ■ Dr. Peter W. Schumann, Gesellschaft ■ Stefan Kügler, Förderverein Trinitatis- zur Förderung einer Gedenkstätte für kirchruine den Sophienkirche Dresden e. V. ■ Cornelia Kraft ■ Friedrich Reichert, Stadtmuseum ■ Christa Lauffer, May Landschafts- ■ Pfarrer Klaus Vesting, Evangelisch- architekten reformierte-Gemeinde Abb. 2: Rathaus und Evangelisch-reformierte Kirche, nach 1945 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort 4 Die St.-Pauli-Kirche 40 Manfred Wiemer Joachim Liebers Einführung 5 Die Evangelisch-reformierte Kirche 44 Prof. Gerhard Glaser Dr. Manfred Dreßler † Die Sophienkirche 6 Die Trinitatiskirche 48 Dietmar Schreier und Manfred Lauffer † Dirk -

The American Bach Society the Westfield Center

The Eastman School of Music is grateful to our festival sponsors: The American Bach Society • The Westfield Center Christ Church • Memorial Art Gallery • Sacred Heart Cathedral • Third Presbyterian Church • Rochester Chapter of the American Guild of Organists • Encore Music Creations The American Bach Society The American Bach Society was founded in 1972 to support the study, performance, and appreciation of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach in the United States and Canada. The ABS produces Bach Notes and Bach Perspectives, sponsors a biennial meeting and conference, and offers grants and prizes for research on Bach. For more information about the Society, please visit www.americanbachsociety.org. The Westfield Center The Westfield Center was founded in 1979 by Lynn Edwards and Edward Pepe to fill a need for information about keyboard performance practice and instrument building in historical styles. In pursuing its mission to promote the study and appreciation of the organ and other keyboard instruments, the Westfield Center has become a vital public advocate for keyboard instruments and music. By bringing together professionals and an increasingly diverse music audience, the Center has inspired collaborations among organizations nationally and internationally. In 1999 Roger Sherman became Executive Director and developed several new projects for the Westfield Center, including a radio program, The Organ Loft, which is heard by 30,000 listeners in the Pacific 2 Northwest; and a Westfield Concert Scholar program that promotes young keyboard artists with awareness of historical keyboard performance practice through mentorship and concert opportunities. In addition to these programs, the Westfield Center sponsors an annual conference about significant topics in keyboard performance. -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J. -

The J. C. Bach – Mozart Connection

The J. C. Bach – Mozart Connection ADENA PORTOWITZ “Few composers, Leopold Mozart apart, exercised a comparable influence on the boy or indeed the man.” (Stanley Sadie)1 Johann Christian Bach (1735-82), eighteenth-century composer par excellence, was one of the most respected musicians of his time. Overshadowed by the achievements of the later Classical composers, and totally forgotten during the nineteenth century,2 he reemerged as a composer of significant stature during the twentieth century.3 Focusing on his contribution to music history and his close relationship with Mozart, this renewed interest resulted in numerous scholarly studies, culminating in Ernest Warburton’s monumental 48-volume publication, The Collected Works of Johann Christian Bach.4 Reflecting on these changing fortunes, we may ask ourselves what the factors were that led to a reassessment of Bach’s contribution to the Classical style; what ways these factors were related to Mozart’s high regard for Bach; and why modern Mozartiana has included a revival of Bach’s music. Addressing these issues, this article opens with a biographical survey, illustrating the context of Bach’s life and work. It then continues with a discussion of the Bach-Mozart connection, and concludes with brief comparative analyses of the first movements of Bach’s Symphony Opus 6 No. 65 and Mozart’s Symphony K. 183/173dB, both in the key of g minor. 1 Stanley Sadie, Mozart: The Early Years, 1756-1781 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 89. 2 Bach’s symphonies and concertantes continued to be performed in London for another decade after his death, using published and manuscript scores.