The Royal Navy and the Question of Imperial Defence at the 1887

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Account of the Origin and Progress of British Influence in Malaya by Sir Frank^,Swettenham,K.C.M.G

pf^: X 1 jT^^Hi^^ ^^^^U^^^ m^^^l^0l^ j4 '**^4sCidfi^^^fc^^l / / UCSB LIBRAIX BRITISH MALAYA BRITISH MALAYA AN ACCOUNT OF THE ORIGIN AND PROGRESS OF BRITISH INFLUENCE IN MALAYA BY SIR FRANK^,SWETTENHAM,K.C.M.G. LATE GOVERNOR &c. OF THE STRAITS COLONY & HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR THE FEDERATED MALAY STATES WITH A SPECIALLY COMPILED MAP NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS RE- PRODUCED FROM PHOTOGRAPHS 6f A FRONTISPIECE IN PHOTOGRAVURE 15>W( LONDON i JOHN LANE THE BODLEY HEAD NEW YORK: JOHN LANE COMPANY MDCCCCVH Plymouth: william brendon and son, ltd., printers PREFACE is an article of popular belief that Englishmen are born sailors probably it would be more true to IT ; say that they are born administrators. The English- man makes a good sailor because we happen to have hit upon the right training to secure that end ; but, though the Empire is large and the duties of administra- tion important, we have no school where they are taught. Still it would be difficult to devise any responsibility, how- ever onerous and unattractive, which a midshipman would not at once undertake, though it had no concern with sea or ship. Moreover, he would make a very good attempt to solve the problem, because his training fits him to deal intelligently with the unexpected. One may, however, question whether any one but a midshipman would have willingly embarked upon a voyage to discover the means of introducing order into the Malay States, when that task was thrust upon the British Government in 1874. The object of this book is to explain the circumstances under which the experiment was made, the conditions which prevailed, the features of the country and the character of the people ; then to describe the gradual evolution of a system of administration which has no exact parallel, and to tell what this new departure has done for Malaya, what effect it has had on the neighbour- ing British possessions. -

THE UNIVERSITY Heritage Trail

THE UNIVERSITY Heritage Trail Established by The University of Auckland Business School www.business.auckland.ac.nz ARCHITECTURAL AND HISTORIC ATTRACTIONS The University of Auckland Business School is proud to establish the University Heritage Trail through the Business History Project as our gift to the City of Auckland in 2005, our Centenary year. In line with our mission to be recognised as one of Asia-Pacific’s foremost research-led business schools, known for excellence and innovation in research, we support the aims of the Business History Project to identify, capture and celebrate the stories of key contributors to New Zealand and Auckland’s economy. The Business History Project aims to discover the history of Auckland’s entrepreneurs, traders, merchants, visionaries and industrialists who have left a legacy of inspiring stories and memorable landmarks. Their ideas, enthusiasm and determination have helped to build our nation’s economy and encourage talent for enterprise. The University of Auckland Business School believes it is time to comprehensively present the remarkable journey that has seen our city grow from a collection of small villages to the country’s commercial powerhouse. Capturing the history of the people and buildings of our own University through The University Heritage Trail will enable us to begin to understand the rich history at the doorstep of The University of Auckland. Special thanks to our Business History project sponsors: The David Levene Charitable Trust DB Breweries Limited Barfoot and Thompson And -

Annual Report2003&Stats

���������������������������������� ������������� ����������� 1 Libraries Board of South Australia Annual Report 2002-2003 Annual report production Coordination and editing by Carolyn Spooner, Project Officer. Assistance by Danielle Disibio, Events and Publications Officer. Cover photographs reproduced with kind permission of John Gollings Photography. Desktop publishing by Anneli Hillier, Reformatting Officer. Scans by Mario Sanchez, Contract Digitiser. Cover and report design by John Nowland Design. Published in Adelaide by the Libraries Board of South Australia, 2003. Printed by CM Digital. ISSN 0081-2633. If you require further information on the For information on the programs or services programs or services of the State Library please of PLAIN Central Services please write to the write to the Director, State Library of South Associate Director, PLAIN Central Services, Australia, GPO Box 419, Adelaide SA 5001, or 8 Milner Street, Hindmarsh SA 5007, or check call in person to the State Library on North the website at Terrace, Adelaide, or check the website at www.plain.sa.gov.au www.slsa.sa.gov.au Telephone (08) 8207 7200 Telephone (08) 8348 2311 Freecall 1800 182 013 Facsimile (08) 8340 2524 Facsimile (08) 8207 7207 Email [email protected] Email [email protected] 2 Libraries Board of South Australia 3 Libraries Board of South Australia Annual Report 2002-2003 Annual Report 2002-2003 CONTENTS The Libraries Board of South Australia 4 Chairman’s message 5 Organisation structure and Freedom of Information 6 State Library of South -

SIR WILLIAM JERVOIS Papers, 1877-78 Reel M1185

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT SIR WILLIAM JERVOIS Papers, 1877-78 Reel M1185 Mr John Jervois Lloyd’s Lime Street London EC3M 7HL National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1981 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Sir William Francis Drummond Jervois (1821-1897) was born at Cowes on the Isle of Wight and educated at Dr Burney’s Academy near Gosport and the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. He was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Royal Engineers in 1839. He was posted to the Cape of Good Hope in 1841, where he began the first survey of British Kaffirland. He subsequently held a number of posts, including commanding royal engineer for the London district (1855-56), assistant inspector-general of fortifications at the War Office (1856-62) and secretary to the defence committee (1859-75). He was made a colonel in 1867 and knighted in 1874. In 1875 Jervois was sent to Singapore as governor of the Straits Settlements. He antagonised the Colonial Office by pursuing an interventionist policy in the Malayan mainland, crushing a revolt in Perak with troops brought from India and Hong Kong. He was ordered to back down and the annexation of Perak was forbidden. He compiled a report on the defences of Singapore. In 1877, accompanied by Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Scratchley, Jervois carried out a survey of the defences of Australia and New Zealand. In the same year he was promoted major-general and appointed governor of South Australia. He immediately faced a political crisis, following the resignation of the Colton Ministry. There was pressure on Jervois to dissolve Parliament, but he appointed James Boucaut as premier and there were no further troubles. -

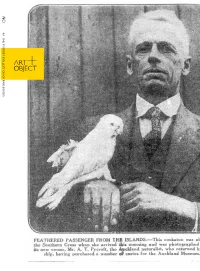

Auckland Like Many Other Lay Enthusiasts, He Made Considerable

49 THE PYCROFT COLLECTION OF RARE BOOKS Arthur Thomas Pycroft ART + OBJECT (1875–1971) 3 Abbey Street Arthur Pycroft was the “essential gentleman amateur”. Newton Auckland Like many other lay enthusiasts, he made considerable PO Box 68 345 contributions as a naturalist, scholar, historian and Newton conservationist. Auckland 1145 He was educated at the Church of England Grammar Telephone: +64 9 354 4646 School in Parnell, Auckland’s first grammar school, where his Freephone: 0 800 80 60 01 father Henry Thomas Pycroft a Greek and Hebrew scholar Facsimile: +64 9 354 4645 was the headmaster between 1883 and 1886. The family [email protected] lived in the headmaster’s residence now known as “Kinder www.artandobject.co.nz House”. He then went on to Auckland Grammar School. On leaving school he joined the Auckland Institute in 1896, remaining a member Previous spread: for 75 years, becoming President in 1935 and serving on the Council for over 40 years. Lots, clockwise from top left: 515 Throughout this time he collaborated as a respected colleague with New Zealand’s (map), 521, 315, 313, 513, 507, foremost men of science, naturalists and museum directors of his era. 512, 510, 514, 518, 522, 520, 516, 519, 517 From an early age he developed a “hands on” approach to all his interests and corresponded with other experts including Sir Walter Buller regarding his rediscovery Rear cover: of the Little Black Shag and other species which were later included in Buller’s 1905 Lot 11 Supplement. New Zealand’s many off shore islands fascinated him and in the summer of 1903-04 he spent nearly six weeks on Taranga (Hen Island), the first of several visits. -

The Governor-General of New Zealand Dame Patsy Reddy

New Zealand’s Governor General The Governor-General is a symbol of unity and leadership, with the holder of the Office fulfilling important constitutional, ceremonial, international, and community roles. Kia ora, nga mihi ki a koutou Welcome “As Governor-General, I welcome opportunities to acknowledge As New Zealand’s 21st Governor-General, I am honoured to undertake success and achievements, and to champion those who are the duties and responsibilities of the representative of the Queen of prepared to assume leadership roles – whether at school, New Zealand. Since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, the role of the Sovereign’s representative has changed – and will continue community, local or central government, in the public or to do so as every Governor and Governor-General makes his or her own private sector. I want to encourage greater diversity within our contribution to the Office, to New Zealand and to our sense of national leadership, drawing on the experience of all those who have and cultural identity. chosen to make New Zealand their home, from tangata whenua through to our most recent arrivals from all parts of the world. This booklet offers an insight into the role the Governor-General plays We have an extraordinary opportunity to maximise that human in contemporary New Zealand. Here you will find a summary of the potential. constitutional responsibilities, and the international, ceremonial, and community leadership activities Above all, I want to fulfil New Zealanders’ expectations of this a Governor-General undertakes. unique and complex role.” It will be my privilege to build on the legacy The Rt Hon Dame Patsy Reddy of my predecessors. -

Pro Patria Commemorating Service

PRO PATRIA COMMEMORATING SERVICE Forward Representative Colonel Governor of South Australia His Excellency the Honorable Hieu Van Le, AO Colonel Commandant The Royal South Australia Regiment Brigadier Tim Hannah, AM Commanding Officer 10th/27th Battalion The Royal South Australia Regiment Lieutenant Colonel Graham Goodwin Chapter Title One Regimental lineage Two Colonial forces and new Federation Three The Great War and peace Four The Second World War Five Into a new era Six 6th/13th Light Battery Seven 3rd Field Squadron Eight The Band Nine For Valour Ten Regimental Identity Eleven Regimental Alliances Twelve Freedom of the City Thirteen Sites of significance Fourteen Figures of the Regiment Fifteen Scrapbook of a Regiment Sixteen Photos Seventeen Appointments Honorary Colonels Regimental Colonels Commanding Officers Regimental Sergeants Major Nineteen Commanding Officers Reflections 1987 – 2014 Representative Colonel His Excellency the Honorable Hieu Van Le AO Governor of South Australia His Excellency was born in Central Vietnam in 1954, where he attended school before studying Economics at the Dalat University in the Highlands. Following the end of the Vietnam War, His Excellency, and his wife, Lan, left Vietnam in a boat in 1977. Travelling via Malaysia, they were one of the early groups of Vietnamese refugees to arrive in Darwin Harbour. His Excellency and Mrs Le soon settled in Adelaide, starting with three months at the Pennington Migrant Hostel. As his Tertiary study in Vietnam was not recognised in Australia, the Governor returned to study at the University of Adelaide, where he earned a degree in Economics and Accounting within a short number of years. In 2001, His Excellency’s further study earned him a Master of Business Administration from the same university. -

LORD CARRINGTON Papers, 1860-1928 Reels M917-32

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT LORD CARRINGTON Papers, 1860-1928 Reels M917-32 Brigadier A.A. Llewellyn Palmer The Manor House Great Somerford Chippenham, Wiltshire National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1972 CONTENTS Page 3 Biographical note 4 Selected speeches, letters and recollections 6 Australian correspondence, 1885-1918 8 Australian papers, 1877-91 9 Newspaper cuttings and printed works, 1882-1915 11 General correspondence, 1885-1928 14 Portraits 14 Miscellaneous papers, 1860-1914 17 Diaries of Lady Carrington, 1881-1913 19 Diaries of Lord Carrington, 1888-93 2 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Charles Robert Carrington (1843-1928), 3rd Baron Carrington (succeeded 1868), 1st Earl Carrington (created 1895), 1st Marquess of Lincolnshire (created 1912), was born in London. He was educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge. As a schoolboy, he was introduced to the Prince of Wales and they were to be close friends for over fifty years. Carrington was the Liberal member for High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire in 1865-68. He became a captain in the Royal House Guards in 1869 and in 1875-76 was aide-de-camp to the Prince of Wales on his tour of India. In 1881 he was appointed lieutenant-colonel of the Royal Buckinghamshire Infantry. In 1878 he married Cecilia (Lily) Harbord, the daughter of Baron Suffield. In 1885, at the urging of the Prince of Wales, Carrington was appointed governor of New South Wales. With his wife and three daughters, he arrived in Sydney in December 1885 and they remained in the colony for almost five years. The Carringtons were a popular couple and generous hosts, especially during the celebrations of Queen Victoria’s jubilee in 1887 and the New South Wales centenary celebrations in 1888. -

Military Aspects of Hydrogeology: an Introduction and Overview

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 28, 2021 Military aspects of hydrogeology: an introduction and overview JOHN D. MATHER* & EDWARD P. F. ROSE Department of Earth Sciences, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: The military aspects of hydrogeology can be categorized into five main fields: the use of groundwater to provide a water supply for combatants and to sustain the infrastructure and defence establishments supporting them; the influence of near-surface water as a hazard affecting mobility, tunnelling and the placing and detection of mines; contamination arising from the testing, use and disposal of munitions and hazardous chemicals; training, research and technology transfer; and groundwater use as a potential source of conflict. In both World Wars, US and German forces were able to deploy trained hydrogeologists to address such problems, but the prevailing attitude to applied geology in Britain led to the use of only a few, talented individuals, who gained relevant experience as their military service progressed. Prior to World War II, existing techniques were generally adapted for military use. Significant advances were made in some fields, notably in the use of Norton tube wells (widely known as Abyssinian wells after their successful use in the Abyssinian War of 1867/1868) and in the development of groundwater prospect maps. Since 1945, the need for advice in specific military sectors, including vehicle mobility, explosive threat detection and hydrological forecasting, has resulted in the growth of a group of individuals who can rightly regard themselves as military hydrogeologists. -

New Zealand Rulers and Statesmen from 1840 To

NEWZfiALAND UUUflflUUUW w RULERS AND STATESMEN I i iiiiliiiiiiiiii 'Hi"' ! Ml! hill i! I m'/sivrr^rs''^^'^ V}7^: *'- - ^ v., '.i^i-:f /6 KDWARD CIRHON WAKEKIELI). NEW ZEALAND RULERS AND STATESMEN Fro}n 1840 to 1897 WILLIAM GISBORNE FOK.MFRLV A IMEMREK OF THE HOUSE OK KE FRESENTATIVES, AND A RESPONSIIiLE MINISTER, IN NEW ZEALAND WITH NUMEROUS PORTRAITS REVISED AND ENLARGED EDITION P. C. D. LUCKIE LONDON SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON & COMPANY Liviitcd Fetter Lane, Fleet Street, B.C. 1897 — mi CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. Introductory—Natives— First colonization—Governor Hobson Chief Justice Sir William Martin —-Attorney-General Swain- son—Bishop Selwyn—Colonel Wakefield—-New Zealand Company—Captain Wakefield — Wairau massacre— Raupa- raha—Acting-Governor Shortland—Governor Fitzroy . CHAPTER II. Governor Sir George Grey, K.C.B.—Lieutenant-Governor Eyre —New Constitution— Progress of Colonization— Recall of Governor Sir George Grey ....... 33 CHAPTER III. Representative institutions — Acting-Governor Wynyard—Mr. Edward Gibbon Wakefield—Mr. James Edward FitzGerald Dr. Featherston—Mr. Henry Sewell—Sir Frederick Whitaker —Sir Francis Bell— First Parliament—Responsible govern- ment—Native policy—Sir Edward Stafford—Mr. William Richmond—Mr. James Richmond—Sir Harry Atkinson Richmond-Atkinson family .... • • • 57 CHAPTER IV. Sir William Fox— Sir W'illiam Fitzherbert—Mr. Alfred Domett —Sir John Hall ......... 102 —— vi Contents CHAPTER V. I'AGE Session of 1856— Stafford Ministry— Provincial Question— Native Government—Land League—King Movement—Wi Tami- hana— Sir Donald McLean— Mr. F. D. Fenton —Session of 1858—Taranaki Native Question—Waitara War—Fox Ministry—Mr. Reader Wood—Mr. Walter Mantell— Respon- sible Government— Return of Sir George Grey as Governor —Domett Ministry—Whitaker-Fox Ministry . -

Defences of the Colony

(No. 37.) 187 8. TA. S M· A NI A. HOUSE OF A·ssEMBLY. DEFENCES OF THE COLONY. I.aid upon the Table by the Colonial Treasurer, and ordered by the Houae to· be printed, July 16, 1878. · · · · r) · DEFENCES OF THE COLONY. • ; I/ :..: :·. MEMORANDUM FOR MINISTERS• .... \•,. ON and from ~ny.first arrival in the Colony I have considered it'to be my duty to call the attention of Ministers to the question of Defence. I have ever held that no country has a· right to claim the .:privileges of self-governro.ent. and to ignore the responsibilities of making such provision for self-defence as may be within its means. Tasmania clearly cannot undertake works or maintain a force sufficient to defend it against any powerful expedition : this can only be effected by a federation for su:ch purposes with other neighbouring colonies, and in part at their expense; and such co-operation would be but just, as even the temporary occupation by an enemy of a strong position in Tasmania would cripple their commerce and destroy their resources, perhaps as much as the occupation of part of their own territory for the same purposes would do. But such an occupation in force is, for reasons which are obvious, and which I will not stop to detail. a contingency which is not at present in the category of immediate probabilities. In the case of Great Britain being involved in a war, it is, however, immediately probable that armed cruisers would attempt to levy contributions on undefended British settlements, and to cripple their commerce. -

The Administrative History of the British Dependencies in the Further East

Livre de Lyon Academic Works of Livre de Lyon Social, Humanity and Administrative Sciences 2016 The Administrative History of The British Dependencies in The Further East Henry Morse Stephens Follow this and additional works at: https://academicworks.livredelyon.com/soc_hum_ad_sci Part of the Asian History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Stephens, Henry Morse, "The Administrative History of The British Dependencies in The Further East" (2016). Social, Humanity and Administrative Sciences. 10. https://academicworks.livredelyon.com/soc_hum_ad_sci/10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Livre de Lyon, an international publisher specializing in academic books and journals. Browse more titles on Academic Works of Livre de Lyon, hosted on Digital Commons, an Elsevier platform. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY OF THE BRITISH DEPENDENCIES IN THE FURTHER EAST The striking diversity of Great Britain’s administration of her various dependencies in the Malay Peninsula and around the China Sea is due to the history of their establishment and growth. Thrown in comparatively close proximity, can be seen four distinct methods of governing Asiatic possessions. There exist almost side by side: (1) the Straits Settlements, exhibiting the system character istic of the government of India, that of holding certain strategic points under direct British adminis- tration, while controlling, as a dependent