Hirschians Debate the True Meaning of Hirsch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Contemporary Ethics Part 9: the Written and Oral Torah by Rabbi Dr Moshe Freedman, New West End Synagogue

Vayetze Vol.31 No.11.qxp_Layout 1 31/10/2018 10:58 Page 4 Jewish Contemporary Ethics Part 9: The Written and Oral Torah by Rabbi Dr Moshe Freedman, New West End Synagogue The last article introduced animals which were “ritually clean” and just one the idea that God’s Divine pair of animals which were “not ritually clean” morality is not simply into the Ark (Bereishit 7:2). The Talmud explains imposed on humanity, that Noach studied the laws of the kashrut of but requires an eternal animals, and that he needed more kosher covenant and ongoing animals in order to offer them to God after leaving relationship between God the ark (Zevachim 116a). and mankind. The next section of this series will try to analyse the nature, The Talmud notes that Avraham himself deduced meaning and mechanics of that covenant. both the existence of God and the mitzvot, and kept the entire Torah (Yoma 28b). Avraham then When we refer to ‘the Torah’ we often mean the taught Torah to his family, who also kept its laws Five Books of Moshe. The word itself derives (see Beresihit 18:19 and 26:5). This generates a from the Hebrew root hry, which in this form number of fascinating conundrums where the means to guide or teach (see Vayikra 10:11). Yet actions of our forefathers appear to contradict the commentators write that the concept of ‘the Torah law. While a detailed resolution lies beyond Torah’ is much deeper and more complex. the scope of this series, it shows that Avraham not only recognised the Unity of God, but that he We may be used to thinking that the Torah was was the progenitor and advocate of pre-Sinaitic given to the Jewish people via Moshe at Mount Torah, which was Monotheistic. -

Orthodoxy in American Jewish Life1

ORTHODOXY IN AMERICAN JEWISH LIFE1 by CHARLES S. LIEBMAN INTRODUCTION • DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF ORTHODOXY • EARLY ORTHODOX COMMUNITY • UNCOMMITTED ORTHODOX • COM- MITTED ORTHODOX • MODERN ORTHODOX • SECTARIANS • LEAD- ERSHIP • DIRECTIONS AND TENDENCIES • APPENDLX: YESHIVOT PROVIDING INTENSIVE TALMUDIC STUDY A HIS ESSAY is an effort to describe the communal aspects and institutional forms of Orthodox Judaism in the United States. For the most part, it ignores the doctrines, faith, and practices of Orthodox Jews, and barely touches upon synagogue hie, which is the most meaningful expression of American Orthodoxy. It is hoped that the reader will find here some appreciation of the vitality of American Orthodoxy. Earlier predictions of the demise of 11 am indebted to many people who assisted me in making this essay possible. More than 40, active in a variety of Orthodox organizations, gave freely of their time for extended discussions and interviews and many lay leaders and rabbis throughout the United States responded to a mail questionnaire. A number of people read a draft of this paper. I would be remiss if I did not mention a few by name, at the same time exonerating them of any responsibility for errors of fact or for my own judgments and interpretations. The section on modern Orthodoxy was read by Rabbi Emanuel Rackman. The sections beginning with the sectarian Orthodox to the conclusion of the paper were read by Rabbi Nathan Bulman. Criticism and comments on the entire paper were forthcoming from Rabbi Aaron Lichtenstein, Dr. Marshall Ski are, and Victor Geller, without whose assistance the section on the number of Orthodox Jews could not have been written. -

Kabbalah As a Shield Against the “Scourge” of Biblical Criticism: a Comparative Analysis of the Torah Commentaries of Elia Benamozegh and Mordecai Breuer

Kabbalah as a Shield against the “Scourge” of Biblical Criticism: A Comparative Analysis of the Torah Commentaries of Elia Benamozegh and Mordecai Breuer Adiel Cohen The belief that the Torah was given by divine revelation, as defined by Maimonides in his eighth principle of faith and accepted collectively by the Jewish people,1 conflicts with the opinions of modern biblical scholarship.2 As a result, biblical commentators adhering to both the peshat (literal or contex- tual) method and the belief in the divine revelation of the Torah, are unable to utilize the exegetical insights associated with the documentary hypothesis developed by Wellhausen and his school, a respected and accepted academic discipline.3 As Moshe Greenberg has written, “orthodoxy saw biblical criticism in general as irreconcilable with the principles of Jewish faith.”4 Therefore, in the words of D. S. Sperling, “in general, Orthodox Jews in America, Israel, and elsewhere have remained on the periphery of biblical scholarship.”5 However, the documentary hypothesis is not the only obstacle to the religious peshat commentator. Theological complications also arise from the use of archeolog- ical discoveries from the ancient Near East, which are analogous to the Torah and can be a very rich source for its interpretation.6 The comparison of biblical 246 Adiel Cohen verses with ancient extra-biblical texts can raise doubts regarding the divine origin of the Torah and weaken faith in its unique sanctity. The Orthodox peshat commentator who aspires to explain the plain con- textual meaning of the Torah and produce a commentary open to the various branches of biblical scholarship must clarify and demonstrate how this use of modern scholarship is compatible with his or her belief in the divine origin of the Torah. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Introduction to the Purpose of Man in the World

INTRODUCTION TO THE PURPOSE OF MAN IN THE WORLD he Morasha syllabus features a series of classes addressing the purpose of man in Tthe world. These shiurim address fundamental principles of Jewish philosophy including the relationship of the body and the soul, free will, the centrality of chesed (loving kindness), hashgachah pratit (Divine providence) and striving to emulate God. However, these principles revolve around even more basic issues that need to be explored first: What is the purpose of existence? Is there a purpose of man in this world, and if so, what is it? Why did God place us in a physical, material world? This shiur provides an approach to these questions which then serves as the underpinning for subsequent classes on fundamental Jewish principles. The evolutionary biologist and atheist Richard Dawkins (in River out of Eden) has the following to say about purpose: The universe that we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference. Judaism teaches that purpose is inherent to the world, and inherent to human existence. As the US National Academy of Sciences asserts (Teaching About Evolution and the Nature of Science), there is little room for science in this discussion: “Whether there is a purpose to the universe or a purpose for human existence are not questions for science.” In stark contrast to Dawkins, this class presents the Jewish outlook on purpose, and will address the following questions: Why did God create the world? Why are we here? Was the world created for God’s sake, or for ours? What are the “important things in life?” Do I have an individual mission in life? 1 Purpose of Man in the World INTRODUCTION TO THE PURPOSE OF MAN IN THE WORLD Class Outline: Introduction: In Only Nine Million Years We’ll Reach Kepler-22B Section I: Why Did God Create the World? Part A. -

Rav Yisroel Salanter's Grave Has Finally Been Located by A

The RYS Daily 3/13/07 The Resting Place of RYS From http://chareidi.shemayisrael.com/archives5761/nasso/NSOarysrl.htm Rav Yisroel Salanter's Grave has Finally been Located By A. Cohen Last week we were privileged to hear some exciting news: with obvious siyata deShmaya the burial place of HaRav Yisroel Salanter ztv"l in the ancient cemetery of Koenigsberg was located. Those involved in this holy task these past few years could not find an adequate way of giving expression to their feelings of joy and gratitude to the Creator. "They that sow in tears, shall reap in joy." Many years of tireless work to locate the final resting place of the founder of the mussar movement and guide of the yeshiva world during the last few generations finally bore fruit. No joy is as great as that of having doubts and uncertainties resolved. However it is too early to congratulate ourselves. We now have to invest all our efforts into recruiting funds for setting up a gravestone befitting this giant figure, and building a mokom tefilloh for the masses who are sure to come in the future to this site, and to continue to rescue the whole of this ancient cemetery and to revive the Jewish community in this town where Rav Yisroel was active in his last years. We must do everything in our power for the sake of this gaon, who created a revolution in Torah and yir'oh in the last few generations and who "through his activities and methods of learning mussar saved all the yeshivos from falling prey to the maskilim and the accursed haskolo" (HaRav Shach shlita in his letter printed in Writings of the Alter of Kelm and his Students). -

Tzedakah As the Defining Social Marker of Jewish Identity

Tzedakah as the Defining Social Marker of Jewish Identity A. The Test of a True Jew: Check the Pocketbook B. Maimonides: Appealing to Jewish Genes – The Perfect “Pitch” “[God] has told you, human being, what is good and what Adonai requires of you: Nothing but to do justice (mishpat), to love kindness (hesed), and to walk humbly with your God.” (Micah 6:8) הִ גִיד לְָך ָאדָ ם מַ ה-ּטוֹב ּומָ ה-יְהוָה ּדוֹרֵ ׁש מִמְ ָך כִ י אִ ם- עֲׂשוֹתמִׁשְ טפָ וְַאהֲבַת חֶסֶ ד וְהַצְ נֵעַ לֶכֶת עִ ם- אֱֹלהֶ יָך. Noam Zion, Hartman Institute, [email protected] – excerpted form from Jewish Giving in Comparative Perspectives: History and Story, Law and Theology, Anthropology and Psychology. Book One: From Each According to One’s Ability: Duties to Poor People from the Bible to the Welfare State and Tikkun Olam Previous Books: A DIFFERENT NIGHT: The Family Participation Haggadah By Noam Zion and David Dishon LEADER'S GUIDE to "A DIFFERENT NIGHT" By Noam Zion and David Dishon A DIFFERENT LIGHT: Hanukkah Seder and Anthology including Profiles in Contemporary Jewish Courage By Noam Zion A Day Apart: Shabbat at Home By Noam Zion and Shawn Fields-Meyer A Night to Remember: Haggadah of Contemporary Voices Mishael and Noam Zion www.haggadahsrus.com 1 Our teachers have said: "If all troubles were assembled on one side and poverty on the other, poverty would outweigh them all." - Midrash Shemot Rabbah 31:14 "The sea of a mighty population, held in galling fetters, heaves uneasily in the tenements.... The gap between the classes in which it surges, unseen, unsuspected by the thoughtless, is widening day by day. -

Rabbi Danziger's Review of Rabbi Elias' 19 Letters

BOOK REVIEW ESSAY Rediscovering the Hirschian Legacy Three books have been published in the past year which illuminate the life and thought of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch. In the following pages, two eminent scholars, Rabbi Shelomoh E. Danziger and Dr. Judith Bleich, explore the world of Rabbi Hirsch and the meaning of his legacy today. THE WORLD OF RABBI S. R. HIRSCH The presentation of biographical and historical background, the moving eyewitness account of the THE NINETEEN LETTERS meeting of Rav Yisrael Salanter and Rav Hirsch, the synopses that preface each Letter, the clarifying com Newly translated and with commentary by Rabbi mentary and the liberal provision of cross-references - Joseph Elias all these inform and fascinate the reader who wishes to Feldheim Publishers, 1995,359 pages understand the world of ideas of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch zt"l. Rabbi Elias has performed an arduous task REVIEWED BY in presenting this well-crafted, valuable work to the RABBI SHELOMOH E. DANZIGER public. Yet, devoted followers ofRav Hirsch, including abbi Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808-1888), the this reviewer, may well object to the numerous views, great Frankfurt rav, was the gaon and tzaddik cited at every opportunity, of those of different orienta R who inspired Western Orthodoxy to conquer, to tion who opposed, and still oppose, Hirschian princi "Toraize," the new derech eretz (i.e., civilization) of the ples. The virtual effect of this is to counteract, or at post-ghetto era. In the words of Dayan Grunfeld: "The least to moderate, some of the most "Hirschian" con universality of Rav Hirsch's mind, the range of his cepts of the Nineteen Letters. -

Guarding Oral Transmission: Within and Between Cultures

Oral Tradition, 25/1 (2010): 41-56 Guarding Oral Transmission: Within and Between Cultures Talya Fishman Like their rabbinic Jewish predecessors and contemporaries, early Muslims distinguished between teachings made known through revelation and those articulated by human tradents. Efforts were made throughout the seventh century—and, in some locations, well into the ninth— to insure that the epistemological distinctness of these two culturally authoritative corpora would be reflected and affirmed in discrete modes of transmission. Thus, while the revealed Qur’an was transmitted in written compilations from the time of Uthman, the third caliph (d. 656), the inscription of ḥadīth, reports of the sayings and activities of the Prophet Muhammad and his companions, was vehemently opposed—even after writing had become commonplace. The zeal with which Muslim scholars guarded oral transmission, and the ingenious strategies they deployed in order to preserve this practice, attracted the attention of several contemporary researchers, and prompted one of them, Michael Cook, to search for the origins of this cultural impulse. After reviewing an array of possible causes that might explain early Muslim zeal to insure that aḥadīth were relayed solely through oral transmission,1 Cook argued for “the Jewish origin of the Muslim hostility to the writing of tradition” (1997:442).2 The Arabic evidence he cites consists of warnings to Muslims that ḥadīth inscription would lead them to commit the theological error of which contemporaneous Jews were guilty (501-03): once they inscribed their Mathnā, that is, Mishna, Jews came to regard this repository of human teachings as a source of authority equal to that of revealed Scripture (Ibn Sacd 1904-40:v, 140; iii, 1).3 As Jewish evidence for his claim, Cook cites sayings by Palestinian rabbis of late antiquity and by writers of the geonic era, which asserted that extra-revelationary teachings are only to be relayed through oral transmission (1997:498-518). -

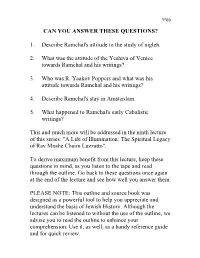

1. Describe Ramchal's Attitude to the Study of Nigleh

c"qa CAN YOU ANSWER THESE QUESTIONS? 1. Describe Ramchal's attitude to the study of nigleh. 2. What was the attitude of the Yeshiva of Venice towards Ramchal and his writings? 3. Who was R. Yaakov Poppers and what was his attitude towards Ramchal and his writings? 4. Describe Ramchal's stay in Amsterdam. 5. What happened to Ramchal's early Cabalistic writings? This and much more will be addressed in the ninth lecture of this series: "A Life of Illumination: The Spiritual Legacy of Rav Moshe Chaim Luzzatto". To derive maximum benefit from this lecture, keep these questions in mind, as you listen to the tape and read through the outline. Go back to these questions once again at the end of the lecture and see how well you answer them. PLEASE NOTE: This outline and source book was designed as a powerful tool to help you appreciate and understand the basis of Jewish History. Although the lectures can be listened to without the use of the outline, we advise you to read the outline to enhance your comprehension. Use it, as well, as a handy reference guide and for quick review. THE EPIC OF THE ETERNAL PEOPLE Presented by Rabbi Shmuel Irons Series IX Lecture #9 A LIFE OF ILLUMINATION: THE SPIRITUAL LEGACY OF RAV MOSHE CHAIM LUZZATTO I. The Controversial Mystic A. 'c ippgi xy`a ,l"z ,gny ip` mbe ,zelbpa ixt iziyr ik z"k gny xy` izi`x (1 zpek ily riaba ip` ygpn j` .ytp zaiyne dninz dlek ik ,dyecwd ezxez iwlg lka el did xak zelbpa iwqr dyere zexzqpd gipn iziid ilele ,de`zn did dfl xy` z"kd iziid `l eil` aexw iziid ilel ik ,z"k zxcd z`n wegx izeid -

A Midrash on Rotulus from Damira, Its Materiality, Scribe, and Date

29 2 Reading in the Provinces: A Midrash on Rotulus from Damira, Its Materiality, Scribe, and Date JUDITH OLSZOWY-SCHLANGER ÉCOLE PRATIQUE DES HAUTES ÉTUDES, SORBONNE, PARIS 30 Judith Olszowy-Schlanger Reading in the Provinces: A Midrash on Rotulus from Damira, Its Materiality, Scribe, and Date 31 ‘A battlefield of books’: this is how Solomon Schechter described the mass of tangled and damaged manuscript debris when he entered the Genizah chamber of the Ben Ezra synagogue in Fustat (Old Cairo) in 1896 (fig. 2.1). This windowless room, together with similar caches in other synagogues and in the cemetery Basatin in Cairo, yielded over 350,000 fragments of manuscripts, kept today in more than seventy collections worldwide.1 Most of the fragments date from the Fatimid and Ayyubid periods: more than ninety-five percent come from books while the rest are fragments of legal documents, letters, and other pragmatic writings. They were preserved thanks to the long-standing Jewish tradition of disposing of old writings with particular respect, founded on the belief that Hebrew texts containing the name of God are sacred: rather than being destroyed or thrown away, worn out books and documents—both holy and trivial—were instead placed in dedicated space, a Genizah, to decay naturally without human intervention. This massive necropolis of discarded writings offers us unprecedented knowledge of Jewish life in Fig. 2.1 medieval Egypt in general and of Jewish book history in particular. Thousands of fragments are Solomon Schechter witnesses to the centrality of Hebrew books in liturgy, in professional activities, and in private at work in the Old University Library, life, as well as offering a mine of information about how these books were made and read: their Cambridge. -

Luzzatto's Derech Hashem

Luzzatto’s Derech Hashem: Understanding the Way of God Shayna Rogozinsky, Jewish Studies Department, McGill University; Montreal August 2010 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Masters in Arts in Jewish Studies © Shayna Rogozinsky, 2010 1 Table of Contents: Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Luzzatto’s Derech Hashem: Understanding the Way of God 5 Introduction 5 On the Introduction to Derech Hashem 14 Fundamentals 19 Prophecy 31 On the Shema 48 Conclusion 52 Bibliography 54 2 Abstract: The aim of this paper is to introduce the reader to Moshe Chaim Luzzatto’s Derech Hashem and Luzzatto’s thought process. It begins with an analysis of the introduction to the work and then examines three major themes: Fundamentals, Prophecy, and the importance of the Shema prayer. Where applicable, comparisons will be made to other Jewish thinkers. Themes will be explained within the Kabbalistic framework that influenced Luzzatto’s work. By the end of the paper the reader should be able to grasp the key elements and reasons that inspired Luzzatto to write this book. Le but de ce document est de présenter le lecteur processus de Moshe Chaim Luzzatto de Derech Hashem et de Luzzatto à pensée. Il commence par une analyse de l'introduction au travail et puis examine trois thèmes importants : Principes fondamentaux, prophétie, et l'importance de la prière de Shema. Là où applicables, des comparaisons seront faites à d'autres penseurs juifs. Des thèmes seront expliqués dans le cadre de Kabbalistic que le travail de Luzzatto influencé. Vers la fin du papier le lecteur devrait pouvoir saisir les éléments clé et les raisons qui a inspiré Luzzatto écrire ce livre.