Guarding Oral Transmission: Within and Between Cultures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

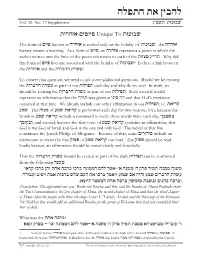

Azharos-Piyuttim Unique to Shavuos

dltzd z` oiadl Vol. 10 No. 17 Supplement b"ryz zereay zexdf`-miheit Unique To zereay The form of heit known as dxdf` is recited only on the holiday of 1zereay. An dxdf` literary means: a warning. As a form of heit, an dxdf` represents a poem in which the author weaves into the lines of the poem references to each of the zeevn b"ixz. Why did this form of heit become associated with the holiday of zereay? Is there a link between the zexdf` and the zexacd zxyr? To answer that question, we need to ask some additional questions. Should we be reciting the zexacd zxyr as part of our zelitz each day and why do we not? In truth, we should be reciting the zexacd zxyr as part of our zelitz. Such a recital would represent an affirmation that the dxez was given at ipiq xd and that G-d’s revelation occurred at that time. We already include one other affirmation in our zelitz; i.e. z`ixw rny. The devn of rny z`ixw is performed each day for two reasons; first, because the words in rny z`ixw include a command to recite these words twice each day, jakya jnewae, and second, because the first verse of rny z`ixw contains an affirmation; that G-d is the G-d of Israel and G-d is the one and only G-d. The recital of that line constitutes the Jewish Pledge of Allegiance. Because of that, some mixeciq include an instruction to recite the first weqt of rny z`ixw out loud. -

The Participation of God and the Torah in Early Kabbalah

religions Article The Participation of God and the Torah in Early Kabbalah Adam Afterman 1,* and Ayal Hayut‑man 2 1 Department of Jewish Philosophy and Talmud, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 6997801, Israel 2 School of Jewish Studies and Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 6997801, Israel; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: All Abrahamic religions have developed hypostatic and semi‑divine perceptions of scrip‑ ture. This article presents an integrated picture of a rich tradition developed in early kabbalah (twelfth–thirteenth century) that viewed the Torah as participating and identifying with the God‑ head. Such presentation could serve scholars of religion as a valuable tool for future comparisons between the various perceptions of scripture and divine revelation. The participation of God and Torah can be divided into several axes: the identification of Torah with the Sefirot, the divine grada‑ tions or emanations according to kabbalah; Torah as the name of God; Torah as the icon and body of God; and the commandments as the substance of the Godhead. The article concludes by examining the mystical implications of this participation, particularly the notion of interpretation as eros in its broad sense, both as the “penetration” of a female Torah and as taking part in the creation of the world and of God, and the notion of unification with Torah and, through it, with the Godhead. Keywords: Kabbalah; Godhead; Torah; scripture; Jewish mysticism; participation in the Godhead 1. Introduction Citation: Afterman, Adam, and Ayal The centrality of the Word of God, as consolidated in scripture, is a central theme in Hayut‑man. -

How Did Halacha Originate Or Did the Rabbis Tell a “Porky”?1 Definitions Written Law the Written Law Is the Torah Or Five Books of Moses

How Did Halacha Originate or Did the Rabbis Tell a “Porky”?1 Definitions Written Law The Written Law is the Torah or Five books of Moses. Also known from the Greek as the Pentateuch. (What status is the Tanach?) Oral Law An Oral Law is a code of conduct in use in a given culture, religion or community …, by which a body of rules of human behaviour is transmitted by oral tradition and effectively respected, ...2 lit. "Torah that is on the ,תורה שבעל פה) According to Rabbinic Judaism, the Oral Torah or Oral Law mouth") represents those laws, statutes, and legal interpretations that were not recorded in the Five lit. "Torah that is in writing"), but nonetheless are ,תורה שבכתב) "Books of Moses, the "Written Torah regarded by Orthodox Jews as prescriptive and co-given. This holistic Jewish code of conduct encompasses a wide swathe of rituals, worship practices, God–man and interpersonal relationships, from dietary laws to Sabbath and festival observance to marital relations, agricultural practices, and civil claims and damages. According to Jewish tradition, the Oral Torah was passed down orally in an unbroken chain from generation to generation of leaders of the people until its contents were finally committed to writing following the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, when Jewish civilization was faced with an existential threat.3 Halacha • all the rules, customs, practices, and traditional laws. (Lauterbach) • the collective body of Jewish religious laws derived from the Written and Oral Torah. (Wikipedia) • Lit. the path that one walks. Jewish law. The complete body of rules and practices that Jews are bound to follow, including biblical commandments, commandments instituted by the rabbis, and binding customs. -

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor. -

Palestinian Citizens of Israel: Agenda for Change Hashem Mawlawi

Palestinian Citizens of Israel: Agenda for Change Hashem Mawlawi Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master‘s degree in Conflict Studies School of Conflict Studies Faculty of Human Sciences Saint Paul University © Hashem Mawlawi, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 PALESTINIAN CITIZENS OF ISRAEL: AGENDA FOR CHANGE ii Abstract The State of Israel was established amid historic trauma experienced by both Jewish and Palestinian Arab people. These traumas included the repeated invasion of Palestine by various empires/countries, and the Jewish experience of anti-Semitism and the Holocaust. This culminated in the 1948 creation of the State of Israel. The newfound State has experienced turmoil since its inception as both identities clashed. The majority-minority power imbalance resulted in inequalities and discrimination against the Palestinian Citizens of Israel (PCI). Discussion of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict tends to assume that the issues of the PCIs are the same as the issues of the Palestinians in the Occupied Territories. I believe that the needs of the PCIs are different. Therefore, I have conducted a qualitative case study into possible ways the relationship between the PCIs and the State of Israel shall be improved. To this end, I provide a brief review of the history of the conflict. I explore themes of inequalities and models for change. I analyze the implications of the theories for PCIs and Israelis in the political, social, and economic dimensions. From all these dimensions, I identify opportunities for change. In proposing an ―Agenda for Change,‖ it is my sincere hope that addressing the context of the Israeli-Palestinian relationship may lead to a change in attitude and behaviour that will avoid perpetuating the conflict and its human costs on both sides. -

The Decline of the Generations (Haazinu)

21 Sep 2020 – 3 Tishri 5781 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Torah discussion on Haazinu The Decline of the Generations Introduction In this week’s Torah portion, Haazinu, Moses tells the Israelites to remember their people’s past: זְכֹר֙יְמֹ֣ות םעֹולָָ֔ ב ִּ֖ ינּו נ֣ שְ ֹותּדֹור־וָד֑ ֹור שְאַַ֤ ל אָב ֙יך֙ וְ יַגֵָ֔דְ ךזְקֵנ ִּ֖יך וְ יֹֹ֥אמְ רּו לְָָֽך Remember the days of old. Consider the years of generation after generation. Ask your father and he will inform you; your elders, and they will tell you. [Deut. 32:7] He then warns them that prosperity (growing “fat, thick and rotund”) and contact with idolaters will cause them to fall away from their faith, so they should keep alive their connection with their past. Yeridat HaDorot Strong rabbinic doctrine: Yeridat HaDorot – the decline of the generations. Successive generations are further and further away from the revelation at Sinai, and so their spirituality and ability to understand the Torah weakens steadily. Also, errors of transmission may have been introduced, especially considering a lot of the Law was oral: מש הק בֵלּתֹורָ ה מ סינַי, ּומְ סָרָ ּהל יהֹושֻׁעַ , ו יהֹושֻׁעַ ל זְקֵנים, ּוזְקֵנים ל נְב יאים, ּונְב יא ים מְ סָ רּוהָ ילְאַנְשֵ נכְ ס ת הַגְדֹולָה Moses received the Torah from Sinai and transmitted it to Joshua, Joshua to the elders, and the elders to the prophets, and the prophets to the Men of the Great Assembly. [Avot 1:1] The Mishnah mourns the Sages of ages past and the fact that they will never be replaced: When Rabbi Meir died, the composers of parables ceased. -

Oral Tradition in the Writings of Rabbinic Oral Torah: on Theorizing Rabbinic Orality

Oral Tradition, 14/1 (1999): 3-32 Oral Tradition in the Writings of Rabbinic Oral Torah: On Theorizing Rabbinic Orality Martin S. Jaffee Introduction By the tenth and eleventh centuries of the Common Era, Jewish communities of Christian Europe and the Islamic lands possessed a voluminous literature of extra-Scriptural religious teachings.1 Preserved for the most part in codices, the literature was believed by its copyists and students to replicate, in writing, the orally transmitted sacred tradition of a family tree of inspired teachers. The prophet Moses was held to be the progenitor, himself receiving at Sinai, directly from the mouth of the Creator of the World, an oral supplement to the Written Torah of Scripture. Depositing the Written Torah for preservation in Israel’s cultic shrine, he had transmitted the plenitude of the Oral Torah to his disciples, and they to theirs, onward in an unbroken chain of transmission. That chain had traversed the entire Biblical period, survived intact during Israel’s subjection to the successive imperial regimes of Babylonia, Persia, Media, Greece, and Rome, and culminated in the teachings of the great Rabbinic sages of Byzantium and Sasanian Babylonia. The diverse written recensions of the teachings of Oral Torah themselves enjoyed a rich oral life in the medieval Rabbinic culture that 1 These broad chronological parameters merely represent the earliest point from which most surviving complete manuscripts of Rabbinic literature can be dated. At least one complete Rabbinic manuscript of Sifra, a midrashic commentary on the biblical book of Leviticus (MS Vatican 66), may come from as early as the eighth century. -

Melilah Agunah Sptib W Heads

Agunah and the Problem of Authority: Directions for Future Research Bernard S. Jackson Agunah Research Unit Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester [email protected] 1.0 History and Authority 1 2.0 Conditions 7 2.1 Conditions in Practice Documents and Halakhic Restrictions 7 2.2 The Palestinian Tradition on Conditions 8 2.3 The French Proposals of 1907 10 2.4 Modern Proposals for Conditions 12 3.0 Coercion 19 3.1 The Mishnah 19 3.2 The Issues 19 3.3 The talmudic sources 21 3.4 The Gaonim 24 3.5 The Rishonim 28 3.6 Conclusions on coercion of the moredet 34 4.0 Annulment 36 4.1 The talmudic cases 36 4.2 Post-talmudic developments 39 4.3 Annulment in takkanot hakahal 41 4.4 Kiddushe Ta’ut 48 4.5 Takkanot in Israel 56 5.0 Conclusions 57 5.1 Consensus 57 5.2 Other issues regarding sources of law 61 5.3 Interaction of Remedies 65 5.4 Towards a Solution 68 Appendix A: Divorce Procedures in Biblical Times 71 Appendix B: Secular Laws Inhibiting Civil Divorce in the Absence of a Get 72 References (Secondary Literature) 73 1.0 History and Authority 1.1 Not infrequently, the problem of agunah1 (I refer throughout to the victim of a recalcitrant, not a 1 The verb from which the noun agunah derives occurs once in the Hebrew Bible, of the situations of Ruth and Orpah. In Ruth 1:12-13, Naomi tells her widowed daughters-in-law to go home. -

A Comparative Study of Jewish Commentaries and Patristic Literature on the Book of Ruth

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF JEWISH COMMENTARIES AND PATRISTIC LITERATURE ON THE BOOK OF RUTH by CHAN MAN KI A Dissertation submitted to the University of Pretoria for the degree of PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR Department of Old Testament Studies Faculty of Theology University of Pretoria South Africa Promoter: PIETER M. VENTER JANUARY, 2010 © University of Pretoria Summary Title : A comparative study of Jewish Commentaries and Patristic Literature on the Book of Ruth Researcher : Chan Man Ki Promoter : Pieter M. Venter, D.D. Department : Old Testament Studies Degree :Doctor of Philosophy This dissertation deals with two exegetical traditions, that of the early Jewish and the patristic schools. The research work for this project urges the need to analyze both Jewish and Patristic literature in which specific types of hermeneutics are found. The title of the thesis (“compared study of patristic and Jewish exegesis”) indicates the goal and the scope of this study. These two different hermeneutical approaches from a specific period of time will be compared with each other illustrated by their interpretation of the book of Ruth. The thesis discusses how the process of interpretation was affected by the interpreters’ society in which they lived. This work in turn shows the relationship between the cultural variants of the exegetes and the biblical interpretation. Both methodologies represented by Jewish and patristic exegesis were applicable and social relevant. They maintained the interest of community and fulfilled the need of their generation. Referring to early Jewish exegesis, the interpretations upheld the position of Ruth as a heir of the Davidic dynasty. They advocated the importance of Boaz’s and Ruth’s virtue as a good illustration of morality in Judaism. -

Orthodox Divorce in Jewish and Islamic Legal Histories

Every Law Tells a Story: Orthodox Divorce in Jewish and Islamic Legal Histories Lena Salaymeh* I. Defining Wife-Initiated Divorce ................................................................................. 23 II. A Judaic Chronology of Wife-Initiated Divorce .................................................... 24 A. Rabbinic Era (70–620 CE) ............................................................................ 24 B. Geonic Era (620–1050 CE) ........................................................................... 27 C. Era of the Rishonim (1050–1400 CE) ......................................................... 31 III. An Islamic Chronology of Wife-Initiated Divorce ............................................... 34 A. Legal Circles (610–750 CE) ........................................................................... 34 B. Professionalization of Legal Schools (800–1050 CE) ............................... 37 C. Consolidation (1050–1400 CE) ..................................................................... 42 IV. Disenchanting the Orthodox Narratives ................................................................ 44 A. Reevaluating Causal Influence ...................................................................... 47 B. Giving Voice to the Geonim ......................................................................... 50 C. Which Context? ............................................................................................... 52 V. An Interwoven Narrative of Wife-Initiated Divorce ............................................ -

The Babylonian Talmud

The Babylonian Talmud translated by MICHAEL L. RODKINSON Book 10 (Vols. I and II) [1918] The History of the Talmud Volume I. Volume II. Volume I: History of the Talmud Title Page Preface Contents of Volume I. Introduction Chapter I: Origin of the Talmud Chapter II: Development of the Talmud in the First Century Chapter III: Persecution of the Talmud from the destruction of the Temple to the Third Century Chapter IV: Development of the Talmud in the Third Century Chapter V: The Two Talmuds Chapter IV: The Sixth Century: Persian and Byzantine Persecution of the Talmud Chapter VII: The Eight Century: the Persecution of the Talmud by the Karaites Chapter VIII: Islam and Its Influence on the Talmud Chapter IX: The Period of Greatest Diffusion of Talmudic Study Chapter X: The Spanish Writers on the Talmud Chapter XI: Talmudic Scholars of Germany and Northern France Chapter XII: The Doctors of France; Authors of the Tosphoth Chapter XIII: Religious Disputes of All Periods Chapter XIV: The Talmud in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries Chapter XV. Polemics with Muslims and Frankists Chapter XVI: Persecution during the Seventeenth Century Chapter XVII: Attacks on the Talmud in the Nineteenth Century Chapter XVIII. The Affair of Rohling-Bloch Chapter XIX: Exilarchs, Talmud at the Stake and Its Development at the Present Time Appendix A. Appendix B Volume II: Historical and Literary Introduction to the New Edition of the Talmud Contents of Volume II Part I: Chapter I: The Combination of the Gemara, The Sophrim and the Eshcalath Chapter II: The Generations of the Tanaim Chapter III: The Amoraim or Expounders of the Mishna Chapter IV: The Classification of Halakha and Hagada in the Contents of the Gemara. -

Down with Britain, Away with Zionism: the 'Canaanites'

DOWN WITH BRITAIN, AWAY WITH ZIONISM: THE ‘CANAANITES’ AND ‘LOHAMEY HERUT ISRAEL’ BETWEEN TWO ADVERSARIES Roman Vater* ABSTRACT: The imposition of the British Mandate over Palestine in 1922 put the Zionist leadership between a rock and a hard place, between its declared allegiance to the idea of Jewish sovereignty and the necessity of cooperation with a foreign ruler. Eventually, both Labour and Revisionist Zionism accommodated themselves to the new situation and chose a strategic partnership with the British Empire. However, dissident opinions within the Revisionist movement were voiced by a group known as the Maximalist Revisionists from the early 1930s. This article analyzes the intellectual and political development of two Maximalist Revisionists – Yonatan Ratosh and Israel Eldad – tracing their gradual shift to anti-Zionist positions. Some questions raised include: when does opposition to Zionist politics transform into opposition to Zionist ideology, and what are the implications of such a transition for the Israeli political scene after 1948? Introduction The standard narrative of Israel’s journey to independence goes generally as follows: when the British military rule in Palestine was replaced in 1922 with a Mandate of which the purpose was to implement the 1917 Balfour Declaration promising support for a Jewish ‘national home’, the Jewish Yishuv in Palestine gained a powerful protector. In consequence, Zionist politics underwent a serious shift when both the leftist Labour camp, led by David Ben-Gurion (1886-1973), and the rightist Revisionist camp, led by Zeev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky (1880-1940), threw in their lot with Britain. The idea of the ‘covenant between the Empire and the Hebrew state’1 became a paradigm for both camps, which (temporarily) replaced their demand for a Jewish state with the long-term prospect of bringing the Yishuv to qualitative and quantitative supremacy over the Palestinian Arabs under the wings of the British Empire.