A Postage Stamp History of the Atom Part I: the Early Years by Michael A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literature Compass Editing Humphry Davy's

1 ‘Work in Progress in Romanticism’ Literature Compass Editing Humphry Davy’s Letters Tim Fulford, Andrew Lacey, Sharon Ruston An editorial team of Tim Fulford (De Montfort University) and Sharon Ruston (Lancaster University) (co-editors), and Jan Golinski (University of New Hampshire), Frank James (the Royal Institution of Great Britain), and David Knight1 (Durham University) (advisory editors) are currently preparing The Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy: a four-volume edition of the c. 1200 surviving letters of Davy (1778-1829) and his immediate circle, for publication with Oxford University Press, in both print and electronic forms, in 2020. Davy was one of the most significant and famous figures in the scientific and literary culture of early nineteenth-century Britain, Europe, and America. Davy’s scientific accomplishments were varied and numerous, including conducting pioneering research into the physiological effects of nitrous oxide (laughing gas); isolating potassium, calcium, and several other metals; inventing a miners’ safety lamp (the bicentenary of which was celebrated in 2015); developing the electrochemical protection of the copper sheeting of Royal Navy vessels; conserving the Herculaneum papyri; writing an influential text on agricultural chemistry; and seeking to improve the quality of optical glass. But Davy’s endeavours were not merely limited to science: he was also a poet, and moved in the same literary circles as Lord Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey, and William Wordsworth. Since his death, Davy has rarely been out of the public mind. He is still the frequent subject of biographies (by, 1 David Knight died in 2018. David gave generously to the Davy Letters Project, and a two-day conference at Durham University was recently held in his memory. -

Atomic History Project Background: If You Were Asked to Draw the Structure of an Atom, What Would You Draw?

Atomic History Project Background: If you were asked to draw the structure of an atom, what would you draw? Throughout history, scientists have accepted five major different atomic models. Our perception of the atom has changed from the early Greek model because of clues or evidence that have been gathered through scientific experiments. As more evidence was gathered, old models were discarded or improved upon. Your task is to trace the atomic theory through history. Task: 1. You will create a timeline of the history of the atomic model that includes all of the following components: A. Names of 15 of the 21 scientists listed below B. The year of each scientist’s discovery that relates to the structure of the atom C. 1- 2 sentences describing the importance of the discovery that relates to the structure of the atom Scientists for the timeline: *required to be included • Empedocles • John Dalton* • Ernest Schrodinger • Democritus* • J.J. Thomson* • Marie & Pierre Curie • Aristotle • Robert Millikan • James Chadwick* • Evangelista Torricelli • Ernest • Henri Becquerel • Daniel Bernoulli Rutherford* • Albert Einstein • Joseph Priestly • Niels Bohr* • Max Planck • Antoine Lavoisier* • Louis • Michael Faraday • Joseph Louis Proust DeBroglie* Checklist for the timeline: • Timeline is in chronological order (earliest date to most recent date) • Equal space is devoted to each year (as on a number line) • The eight (8) *starred scientists are included with correct dates of their discoveries • An additional seven (7) scientists of your choice (from -

John Dalton By: Period 8 Early Years and Education

John Dalton By: Period 8 Early Years and Education • John Dalton was born in the small British village of Eaglesfield, Cumberland, England to a Quaker family. • As a child, John did not have much formal education because his family was rather poor; however, he did acquire a basic foundation in reading, writing, and arithmetic at a nearby Quaker school. • A teacher by the name of John Fletcher took young John Dalton under his wing and introduced him to a great mentor, Elihu Robinson, who was a rich Quaker. • Elihu then agreed to tutor John in mathematics, science, and meteorology. Shortly after he ended his tutoring sessions with Elihu, Dalton began keeping a daily log of the weather and other matters of meteorology. Education continued • His studies of these weather conditions led him to develop theories and hypotheses about mixed gases and water vapor. • He kept this journal of weather recordings his entire life, which later aided him in his observations and recordings of atoms and elements. Accomplishments • In 1794, Dalton became the first • Dalton joined the Manchester to explain color blindness, Literary and Philosophical which he was afflicted with Society and instantly published himself, at one of his public his first book on Meteorological lectures and it is even Observations and Essays. sometimes called Daltonism referring to John Dalton • In this book, John tells of his himself. ideas on gasses and that “in a • The first paper he wrote on this mixture of gasses, each gas matter was entitled exists independently of each Extraordinary facts relating to other gas and acts accordingly,” the visions of colors “in which which was when he’s famous he postulated that shortage in ideas on the Atomic Theory color perception was caused by started to form. -

Atomic Theories and Models

Atomic Theories and Models Answer these questions on your own. Early Ideas About Atoms: Go to http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0905226.html and read the section on “Greek Origins” in order to answer the following: 1. What were Leucippus and Democritus ideas regarding matter? 2. Describe what these philosophers thought the atom looked like? 3. How were the ideas of these two men received by Aristotle, and what was the result on the progress of atomic theory for the next couple thousand years? Alchemists: Go to http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/alchemy and/or http://www.scienceandyou.org/articles/ess_08.shtml to answer the following: 4. What was the ultimate goal of an alchemist? 5. What is the word used to describe changing something of little value into something of higher value? 6. Did any alchemist achieve this goal? John Dalton’s Atomic Theory: Go to http://www.rsc.org/chemsoc/timeline/pages/1803.html and answer the following: 7. When did Dalton form his atomic theory. 8. List the six ideas of Dalton’s theory: a. b. c. d. e. f. Mendeleev: Go to http://www.chemistry.co.nz/mendeleev.htm and/or http://www.aip.org/history/curie/periodic.htm to answer the following: 9. What was Mendeleev’s famous contribution to chemistry? 10. How did Mendeleev arrange his periodic table? 11. Why did Mendeleev leave blank spaces in his periodic table? J. J. Thomson: Go to http://www.universetoday.com/38326/plum-pudding-model/ and http://www.chemheritage.org/discover/online-resources/chemistry-in-history/themes/atomic-and- nuclear-structure/thomson.aspx and http://www.chem.uiuc.edu/clcwebsite/cathode.html and http://www-outreach.phy.cam.ac.uk/camphy/electron/electron_index.htm and http://www.iun.edu/~cpanhd/C101webnotes/modern-atomic-theory/rutherford-model.html to answer the following: 12. -

1 Classical Theory and Atomistics

1 1 Classical Theory and Atomistics Many research workers have pursued the friction law. Behind the fruitful achievements, we found enormous amounts of efforts by workers in every kind of research field. Friction research has crossed more than 500 years from its beginning to establish the law of friction, and the long story of the scientific historyoffrictionresearchisintroducedhere. 1.1 Law of Friction Coulomb’s friction law1 was established at the end of the eighteenth century [1]. Before that, from the end of the seventeenth century to the middle of the eigh- teenth century, the basis or groundwork for research had already been done by Guillaume Amontons2 [2]. The very first results in the science of friction were found in the notes and experimental sketches of Leonardo da Vinci.3 In his exper- imental notes in 1508 [3], da Vinci evaluated the effects of surface roughness on the friction force for stone and wood, and, for the first time, presented the concept of a coefficient of friction. Coulomb’s friction law is simple and sensible, and we can readily obtain it through modern experimentation. This law is easily verified with current exper- imental techniques, but during the Renaissance era in Italy, it was not easy to carry out experiments with sufficient accuracy to clearly demonstrate the uni- versality of the friction law. For that reason, 300 years of history passed after the beginning of the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century before the friction law was established as Coulomb’s law. The progress of industrialization in England between 1750 and 1850, which was later called the Industrial Revolution, brought about a major change in the production activities of human beings in Western society and later on a global scale. -

The World Around Is Physics

The world around is physics Life in science is hard What we see is engineering Chemistry is harder There is no money in chemistry Future is uncertain There is no need of chemistry Therefore, it is not my option I don’t have to learn chemistry Chemistry is life Chemistry is chemicals Chemistry is memorizing things Chemistry is smell Chemistry is this and that- not sure Chemistry is fumes Chemistry is boring Chemistry is pollution Chemistry does not excite Chemistry is poison Chemistry is a finished subject Chemistry is dirty Chemistry - stands on the legacy of giants Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier (1743-1794) Marie Skłodowska Curie (1867- 1934) John Dalton (1766- 1844) Sir Humphrey Davy (1778 – 1829) Michael Faraday (1791 – 1867) Chemistry – our legacy Mendeleev's Periodic Table Modern Periodic Table Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev (1834-1907) Joseph John Thomson (1856 –1940) Great experimentalists Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937) Jagadish Chandra Bose (1858 –1937) Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman (1888-1970) Chemistry and chemical bond Gilbert Newton Lewis (1875 –1946) Harold Clayton Urey (1893- 1981) Glenn Theodore Seaborg (1912- 1999) Linus Carl Pauling (1901– 1994) Master craftsmen Robert Burns Woodward (1917 – 1979) Chemistry and the world Fritz Haber (1868 – 1934) Machines in science R. E. Smalley Great teachers Graduate students : Other students : 1. Werner Heisenberg 1. Herbert Kroemer 2. Wolfgang Pauli 2. Linus Pauling 3. Peter Debye 3. Walter Heitler 4. Paul Sophus Epstein 4. Walter Romberg 5. Hans Bethe 6. Ernst Guillemin 7. Karl Bechert 8. Paul Peter Ewald 9. Herbert Fröhlich 10. Erwin Fues 11. Helmut Hönl 12. Ludwig Hopf 13. Walther Kossel 14. -

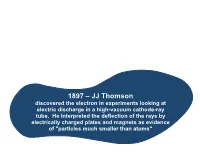

JJ Thomson Discovered the Electron in Experiments Looking At

1897 – JJ Thomson discovered the electron in experiments looking at electric discharge in a high-vacuum cathode-ray tube. He interpreted the deflection of the rays by electrically charged plates and magnets as evidence of "particles much smaller than atoms" 1896 – Henri Becquerel – Though fascinated by materials that exhibited phosphorescence, it was through experiments involving non-phosphorescent uranium salts that he gained his real notoriety. While experimenting with these materials, he discovered natural radioactivity. Through his experiment, he determined that the penetrating radiation came from the uranium itself, without any need of excitation by an external energy source. 1895 – Wilhelm Röentgen – During an experiment, he noticed photographic plates near his equipment glowing. He discovered the glowing was caused by rays emitted by the glass tube used in his investigation. This tube contained a pair of electrodes. As electricity passed between the electrodes, X‑rays were emitted and appeared on the photographic plates. 1887 – Svante Arrhenius ACID = neutral compound that ionizes when dissolved in water and produces the H+ ion and corresponding negative ion. BASE = neutral compound that either dissociates or ionizes in water to give OH- ions and a corresponding positive ion. 1806 - Gay-Lussac - Gay-Lussac's Law states that at constant volume, the pressure of a sample of gas is directly proportional to its temperature in Kelvin. He also provided us with the law of combining volumes - when gases react, the volumes consumed and produced, measured at the same temperature and pressure, are in ratios of small whole numbers. 1804 – John Dalton Once again contributed to the chemical world and gave us the Law of Multiple Proportions – If the same two elements form more than one compound between them, then the combining mass ratios of the two compounds will NOT be the same. -

THE MAN of SCIENCE Steven Shapin

THE IMAGE OF THE MAN OF SCIENCE Steven Shapin The relations between the images of the man of science and the social and cultural realities of scientific roles are both consequential and contingent. Finding out “who the guys were” (to use Sir Lewis Namier’s phrase) does in- deed help to illuminate what kinds of guys they were thought to be, and, for that reason alone, any survey of images is bound to deal – to some extent at least – with what are usually called the realities of social roles.1 At the same time, it must be noted that such social roles are always very substantially con- stituted, sustained, and modified by what members of the culture think is, or should be, characteristic of those who occupy the roles, by precisely whom this is thought, and by what is done on the basis of such thoughts. In socio- logical terms of art, the very notion of a social role implicates a set of norms and typifications – ideals, prescriptions, expectations, and conventions thought properly, or actually, to belong to someone performing an activity of a certain kind. That is to say, images are part of social realities, and the two notions can be distinguished only as a matter of convention. Such conventional distinctions may be useful in certain circumstances. So- cial action – historical and contemporary – very often trades in juxtapositions between image and reality. One might hear it said, for example, that modern American lawyers do not really behave like the high-minded professionals 1 For introductions to pertinent prosopography, see, e.g., Robert M. -

Fill in the Blanks by Using the Notes Found on the Moodle Course. Make a Pocket in Your Journal and Place This Page Into the Pocket

Fill in the blanks by using the notes found on the Moodle Course. Make a pocket in your journal and place this page into the pocket. Title the pocket “Historical Figures” Scientists Contributions Antoine Lavoisier(1743- • Made the first list of elements 1794) - ______________ of • Made the Law of __________ of Mass Chemistry • Discovered how combustion really works • Discovered Oxygen's role in combustion • Created the common ____________ • Discovered ______ and ________ Marie Curie(1867-1934) - • Radioactivity Radiation • Created dynamite Alfred Nobel (1833-1896) - • Created ______ Prize Chemistry • Created the __________________ of Elements Dmitri Mendeleev (1834- 1907)- Chemistry Fill in the blanks by using the notes found on the Moodle Course. Make a pocket in your journal and place this page into the pocket. Title the pocket “Historical Figures” • Discovered the amino acid sequence of _______- Frederick Sanger (1918- _______ 2013) - _________ • DNA sequencing Fritz Haber (1868-1934)- “The Father of Chemical ___________” - • ________________ fixation Physical Chemistry • Large scale synthesis of _______________ • Discovered Electrolysis Humphry Davy (1778-1829) - • Discovered --_______, _______, _______, _______, Chemistry _______, _______, _______, and _______ • Created the first electric lamp - “Davy Lamp” • First to deduce the Acid/Base (B+A=Salt + Water, A + Metal= A Salt) • Created the modern atomic theory • Created the Atomic Mass Unit (amu) Sir John Dalton (1766- • Created first Periodic Table organized by 1844) - _____________ atomic mass • All _______are made up of the same atoms and are practically _______ Fill in the blanks by using the notes found on the Moodle Course. Make a pocket in your journal and place this page into the pocket. -

Physics Celebrity

Born 22 September 1791 Newington Butts, Surrey, England Died 25 August 1867 (aged 75) Hampton Court, Surrey, England Residence: England Fields Physics and Chemistry Known for Faraday's law of induction, Electrochemistry, Faraday effect, Faraday cage, Faraday constant, Faraday cup Faraday's laws of electrolysis, Faraday paradox, Faraday rotator Faraday-efficiency effect, Faraday wave, Faraday wheel, Lines of force Influenced by: Humphry Davy , William Thomas Brande Notable awards Royal Medal (1835 & 1846) Religious stance Sandemanian Michael Faraday was an English chemist and physicist (or natural philosopher, in the terminology of the time) who contributed to the fields of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. Faraday studied the magnetic field around a conductor carrying a DC electric current, and established the basis for the magnetic field concept in physics. He discovered electromagnetic induction, diamagnetism, and laws of electrolysis. He established that magnetism could affect rays of light and that there was an underlying relationship between the two phenomena. His inventions of electromagnetic rotary devices formed the foundation of electric motor technology, and it was largely due to his efforts that electricity became viable for use in technology. As a chemist, Faraday discovered benzene, investigated the clathrate hydrate of chlorine, invented an early form of the bunsen burner and the system of oxidation numbers, and popularized terminology such as anode, cathode, electrode, and ion. Although Faraday received little formal education and knew little of higher mathematics, such as calculus, he was one of the most influential scientists in history. Some historians of science refer to him as the best experimentalist in the history of science. -

Analyse This Th Is Apparatus, Held in London’S Science Museum, Has Some Signifi Cant Purpose — Or Curiosity Value — in the History of Physics

ENDGAME Analyse this Th is apparatus, held in London’s Science Museum, has some signifi cant purpose — or curiosity value — in the history of physics. Can you guess what it is? IT “WEAVES ALGEBRAIC PATTERNS JUST AS THE JACQUARD LOOM WEAVES FLOWERS AND LEAVES”. ANSWER NEXT MONTH. James Prescott Joule was the In 1845, Joule performed his by”. It was only through using son of a wealthy brewer in fi rst paddle-wheel experiment, very sensitive thermometers, Manchester, in the north of churning the water in a constructed especially for this England. He received his early calorimeter using paddles driven experiment, that Joule was able to scientifi c education from by falling weights. Aft er a series reach a consistent result. another well-known Mancunian, of painstaking experiments The paddle-wheel John Dalton. Joule began to using sperm oil and mercury experiments became classics investigate the fast-developing as well as water, he reached the in the history of science. The topic of electricity generation conclusion that a weight of 772 rotating vanes pass through the in the 1830s, wanting to make pounds (350 kg) falling through gaps between a set of fixed vanes comparisons between the a distance of 1 foot (0.3 m) raises to cause maximum resistance effi ciency of various energy the temperature of 1 pound to the water or other liquid. It sources. In the 1840s he became (0.45 kg) of water by 1 degree is not so much the result that is interested in heat, which was Fahrenheit. He called this the remembered now, but the fact then seen as a wasteful by- Last month: ‘mechanical equivalent of heat’. -

Moseley and Atomic Numbers

Rediscovery of the Elements Moseley and Atomic Numbers ing the Industrial Revolution which brought wealth and prosperity to the community. By the mid-1800s, Manchester was the second largest III city in England and gained a reputation as a center of invention and technological progress. In 1781 a prestigious scientific institution was founded— the Literary and Philosophical Society (commonly known as the “Lit. and Phil.”).1 In this society John Dalton (1766–1844),2a who arrived in Manchester in 1793, formulated his atomic theory at the turn of the century.3 At the very same platform4 where Dalton proposed his idea of atoms and James L. Marshall, Beta Eta 1971, and atomic masses (Figures 1, 2), Ernest Rutherford Virginia R. Marshall, Beta Eta 2003, one century later first proposed the nuclear Department of Chemistry, University of atom, a dense positive core surrounded by elec- 5 North Texas, Denton, TX 76203-5070, trons. Ernest Rutherford had arrived in 1907 from [email protected] McGill University, Montreal, Canada.2d At the University of Manchester (then named the Introduction. Manchester in northwest Victoria University of Manchester) he assem- England was founded as a Roman fort in 79 bled a powerful team of gifted individuals Figure 1. This was the Literary and Philosophical A.D. After the Roman departure it evolved into including an Oxford graduate named Henry building at 36 George Street in Manchester built in a typical Medieval village and after a millenni- Gwyn-Jeffreys Moseley (1887–1915), who 1799 which served the scientific community for 140 um matured into a manufacturing giant.