Moseley and Atomic Numbers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literature Compass Editing Humphry Davy's

1 ‘Work in Progress in Romanticism’ Literature Compass Editing Humphry Davy’s Letters Tim Fulford, Andrew Lacey, Sharon Ruston An editorial team of Tim Fulford (De Montfort University) and Sharon Ruston (Lancaster University) (co-editors), and Jan Golinski (University of New Hampshire), Frank James (the Royal Institution of Great Britain), and David Knight1 (Durham University) (advisory editors) are currently preparing The Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy: a four-volume edition of the c. 1200 surviving letters of Davy (1778-1829) and his immediate circle, for publication with Oxford University Press, in both print and electronic forms, in 2020. Davy was one of the most significant and famous figures in the scientific and literary culture of early nineteenth-century Britain, Europe, and America. Davy’s scientific accomplishments were varied and numerous, including conducting pioneering research into the physiological effects of nitrous oxide (laughing gas); isolating potassium, calcium, and several other metals; inventing a miners’ safety lamp (the bicentenary of which was celebrated in 2015); developing the electrochemical protection of the copper sheeting of Royal Navy vessels; conserving the Herculaneum papyri; writing an influential text on agricultural chemistry; and seeking to improve the quality of optical glass. But Davy’s endeavours were not merely limited to science: he was also a poet, and moved in the same literary circles as Lord Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey, and William Wordsworth. Since his death, Davy has rarely been out of the public mind. He is still the frequent subject of biographies (by, 1 David Knight died in 2018. David gave generously to the Davy Letters Project, and a two-day conference at Durham University was recently held in his memory. -

James Chadwick: Ahead of His Time

July 15, 2020 James Chadwick: ahead of his time Gerhard Ecker University of Vienna, Faculty of Physics Boltzmanngasse 5, A-1090 Wien, Austria Abstract James Chadwick is known for his discovery of the neutron. Many of his earlier findings and ideas in the context of weak and strong nuclear forces are much less known. This biographical sketch attempts to highlight the achievements of a scientist who paved the way for contemporary subatomic physics. arXiv:2007.06926v1 [physics.hist-ph] 14 Jul 2020 1 Early years James Chadwick was born on Oct. 20, 1891 in Bollington, Cheshire in the northwest of England, as the eldest son of John Joseph Chadwick and his wife Anne Mary. His father was a cotton spinner while his mother worked as a domestic servant. In 1895 the parents left Bollington to seek a better life in Manchester. James was left behind in the care of his grandparents, a parallel with his famous predecessor Isaac Newton who also grew up with his grandmother. It might be an interesting topic for sociologists of science to find out whether there is a correlation between children educated by their grandmothers and future scientific geniuses. James attended Bollington Cross School. He was very attached to his grandmother, much less to his parents. Nevertheless, he joined his parents in Manchester around 1902 but found it difficult to adjust to the new environment. The family felt they could not afford to send James to Manchester Grammar School although he had been offered a scholarship. Instead, he attended the less prestigious Central Grammar School where the teaching was actually very good, as Chadwick later emphasised. -

Atomic History Project Background: If You Were Asked to Draw the Structure of an Atom, What Would You Draw?

Atomic History Project Background: If you were asked to draw the structure of an atom, what would you draw? Throughout history, scientists have accepted five major different atomic models. Our perception of the atom has changed from the early Greek model because of clues or evidence that have been gathered through scientific experiments. As more evidence was gathered, old models were discarded or improved upon. Your task is to trace the atomic theory through history. Task: 1. You will create a timeline of the history of the atomic model that includes all of the following components: A. Names of 15 of the 21 scientists listed below B. The year of each scientist’s discovery that relates to the structure of the atom C. 1- 2 sentences describing the importance of the discovery that relates to the structure of the atom Scientists for the timeline: *required to be included • Empedocles • John Dalton* • Ernest Schrodinger • Democritus* • J.J. Thomson* • Marie & Pierre Curie • Aristotle • Robert Millikan • James Chadwick* • Evangelista Torricelli • Ernest • Henri Becquerel • Daniel Bernoulli Rutherford* • Albert Einstein • Joseph Priestly • Niels Bohr* • Max Planck • Antoine Lavoisier* • Louis • Michael Faraday • Joseph Louis Proust DeBroglie* Checklist for the timeline: • Timeline is in chronological order (earliest date to most recent date) • Equal space is devoted to each year (as on a number line) • The eight (8) *starred scientists are included with correct dates of their discoveries • An additional seven (7) scientists of your choice (from -

Ernest Rutherford and the Accelerator: “A Million Volts in a Soapbox”

Ernest Rutherford and the Accelerator: “A Million Volts in a Soapbox” AAPT 2011 Winter Meeting Jacksonville, FL January 10, 2011 H. Frederick Dylla American Institute of Physics Steven T. Corneliussen Jefferson Lab Outline • Rutherford's call for inventing accelerators ("million volts in a soap box") • Newton, Franklin and Jefferson: Notable prefiguring of Rutherford's call • Rutherfords's discovery: The atomic nucleus and a new experimental method (scattering) • A century of particle accelerators AAPT Winter Meeting January 10, 2011 Rutherford’s call for inventing accelerators 1911 – Rutherford discovered the atom’s nucleus • Revolutionized study of the submicroscopic realm • Established method of making inferences from particle scattering 1927 – Anniversary Address of the President of the Royal Society • Expressed a long-standing “ambition to have available for study a copious supply of atoms and electrons which have an individual energy far transcending that of the alpha and beta particles” available from natural sources so as to “open up an extraordinarily interesting field of investigation.” AAPT Winter Meeting January 10, 2011 Rutherford’s wish: “A million volts in a soapbox” Spurred the invention of the particle accelerator, leading to: • Rich fundamental understanding of matter • Rich understanding of astrophysical phenomena • Extraordinary range of particle-accelerator technologies and applications AAPT Winter Meeting January 10, 2011 From Newton, Jefferson & Franklin to Rutherford’s call for inventing accelerators Isaac Newton, 1717, foreseeing something like quarks and the nuclear strong force: “There are agents in Nature able to make the particles of bodies stick together by very strong attractions. And it is the business of Experimental Philosophy to find them out. -

John Dalton By: Period 8 Early Years and Education

John Dalton By: Period 8 Early Years and Education • John Dalton was born in the small British village of Eaglesfield, Cumberland, England to a Quaker family. • As a child, John did not have much formal education because his family was rather poor; however, he did acquire a basic foundation in reading, writing, and arithmetic at a nearby Quaker school. • A teacher by the name of John Fletcher took young John Dalton under his wing and introduced him to a great mentor, Elihu Robinson, who was a rich Quaker. • Elihu then agreed to tutor John in mathematics, science, and meteorology. Shortly after he ended his tutoring sessions with Elihu, Dalton began keeping a daily log of the weather and other matters of meteorology. Education continued • His studies of these weather conditions led him to develop theories and hypotheses about mixed gases and water vapor. • He kept this journal of weather recordings his entire life, which later aided him in his observations and recordings of atoms and elements. Accomplishments • In 1794, Dalton became the first • Dalton joined the Manchester to explain color blindness, Literary and Philosophical which he was afflicted with Society and instantly published himself, at one of his public his first book on Meteorological lectures and it is even Observations and Essays. sometimes called Daltonism referring to John Dalton • In this book, John tells of his himself. ideas on gasses and that “in a • The first paper he wrote on this mixture of gasses, each gas matter was entitled exists independently of each Extraordinary facts relating to other gas and acts accordingly,” the visions of colors “in which which was when he’s famous he postulated that shortage in ideas on the Atomic Theory color perception was caused by started to form. -

Atomic Theories and Models

Atomic Theories and Models Answer these questions on your own. Early Ideas About Atoms: Go to http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0905226.html and read the section on “Greek Origins” in order to answer the following: 1. What were Leucippus and Democritus ideas regarding matter? 2. Describe what these philosophers thought the atom looked like? 3. How were the ideas of these two men received by Aristotle, and what was the result on the progress of atomic theory for the next couple thousand years? Alchemists: Go to http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/alchemy and/or http://www.scienceandyou.org/articles/ess_08.shtml to answer the following: 4. What was the ultimate goal of an alchemist? 5. What is the word used to describe changing something of little value into something of higher value? 6. Did any alchemist achieve this goal? John Dalton’s Atomic Theory: Go to http://www.rsc.org/chemsoc/timeline/pages/1803.html and answer the following: 7. When did Dalton form his atomic theory. 8. List the six ideas of Dalton’s theory: a. b. c. d. e. f. Mendeleev: Go to http://www.chemistry.co.nz/mendeleev.htm and/or http://www.aip.org/history/curie/periodic.htm to answer the following: 9. What was Mendeleev’s famous contribution to chemistry? 10. How did Mendeleev arrange his periodic table? 11. Why did Mendeleev leave blank spaces in his periodic table? J. J. Thomson: Go to http://www.universetoday.com/38326/plum-pudding-model/ and http://www.chemheritage.org/discover/online-resources/chemistry-in-history/themes/atomic-and- nuclear-structure/thomson.aspx and http://www.chem.uiuc.edu/clcwebsite/cathode.html and http://www-outreach.phy.cam.ac.uk/camphy/electron/electron_index.htm and http://www.iun.edu/~cpanhd/C101webnotes/modern-atomic-theory/rutherford-model.html to answer the following: 12. -

1 Classical Theory and Atomistics

1 1 Classical Theory and Atomistics Many research workers have pursued the friction law. Behind the fruitful achievements, we found enormous amounts of efforts by workers in every kind of research field. Friction research has crossed more than 500 years from its beginning to establish the law of friction, and the long story of the scientific historyoffrictionresearchisintroducedhere. 1.1 Law of Friction Coulomb’s friction law1 was established at the end of the eighteenth century [1]. Before that, from the end of the seventeenth century to the middle of the eigh- teenth century, the basis or groundwork for research had already been done by Guillaume Amontons2 [2]. The very first results in the science of friction were found in the notes and experimental sketches of Leonardo da Vinci.3 In his exper- imental notes in 1508 [3], da Vinci evaluated the effects of surface roughness on the friction force for stone and wood, and, for the first time, presented the concept of a coefficient of friction. Coulomb’s friction law is simple and sensible, and we can readily obtain it through modern experimentation. This law is easily verified with current exper- imental techniques, but during the Renaissance era in Italy, it was not easy to carry out experiments with sufficient accuracy to clearly demonstrate the uni- versality of the friction law. For that reason, 300 years of history passed after the beginning of the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century before the friction law was established as Coulomb’s law. The progress of industrialization in England between 1750 and 1850, which was later called the Industrial Revolution, brought about a major change in the production activities of human beings in Western society and later on a global scale. -

NEWSLETTER Issue No. 3 February 2011

NEWSLETTER February 2011 Issue no. 3 Rutherford's Gold Foil Experiment by Kara Page See http://np.iop.org for further details Nuclear Physics Group newsletter Feb 2011 Conferences in 2011 The group would particularly like to attract your attention to two major forthcoming conferences that will take place in the UK this year. This year, the IOP Nuclear Physics group will join with 4 other IOP subject groups, High Energy Particle Physics, Gravitational Physics, Astroparticle Physics and Particle Accelerators and Beams Groups, for its annual conference. The five groups will meet together for four days at the University of Glasgow from the 4th of April 2011. This conference will be one of the largest, most exciting and broadest ranged NPP divisional conference ever held. Further information can be found at: http://www.iop.org/events/scientific/conferences/index.html . From the 8th to 12th of August 2011, an international conference celebrating the 100th anniversary of Rutherford’s publication on the atomic nucleus discovery will take place at the University of Manchester. For more information, please visit the web site: http://rutherford.iop.org/. The Geiger–Marsden experiment (also called the Gold foil) was an experiment to probe the structure of the atom performed by Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden in 1909, under the direction of Ernest Rutherford at the Physical Laboratories of the University of Manchester. The unexpected results of the experiment demonstrated for the first time the existence of the atomic nucleus, leading to the downfall of the plum pudding model of the atom, and the development of the Rutherford (or planetary) model. -

Some Personal Overviews by Hugh Jamieson Bruce White Ray Trott

b The development of MEDICAL PHYSICS and BIOMEDICAL ENGINEERING in NEW ZEALAND HOSPITALS 1945-1995 _____________ Some personal overviews by Hugh Jamieson Bruce White Ray Trott Jack Tait Gordon Monks __________ Editor H D Jamieson ___________ Second edition First published 1995 Second edition 1996 Reprinted 2006 ISBN 0-476-01437-9 ii CONTENTS Second edition Index of photographs; Staff lists .. .. .. .. iv Preface, and Preface to Second Edition .. .. .. 1 Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 Early hospital physics in NZ: "Some memory fragments" 3 Around the centres (first appointments in the 6 centres) 7 Supervoltage radiotherapy (summary) .. .. .. 8 Nuclear medicine (summary) .. .. .. .. .. 12 Nuclear medicine imaging (summary) .. .. .. 14 Biomedical engineering (summary) .. .. .. .. 15 Computing in hospitals (summary) .. .. .. .. 18 The ongoing developments (summary); Conclusion .. 20 Photograph, 1954 inaugural NZMPA meeting, Christchurch 21 Hospital/Medical Physics in Dunedin - Hugh Jamieson 23 Wellington Hospital - Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering .. 62 Hospital Physics Beginnings at Auckland Hospital .. 68 The History of Nuclear Medicine in Auckland -Bruce White 71 Auckland Hospital...Medical Physics & Clinical Engineering - Bruce White 83 Hospital/Medical Physics at Palmerston North Hospital - Ray Trott 97 Medical Physics & Bioengineering at Christchurch Hospital - Jack Tait 108 Hospital Physics / Scientific Services at Waikato Hospital - Gordon Monks 135 Retrospect and contemplation .. .. .. .. 151 = = = = = = = = = = = -

The World Around Is Physics

The world around is physics Life in science is hard What we see is engineering Chemistry is harder There is no money in chemistry Future is uncertain There is no need of chemistry Therefore, it is not my option I don’t have to learn chemistry Chemistry is life Chemistry is chemicals Chemistry is memorizing things Chemistry is smell Chemistry is this and that- not sure Chemistry is fumes Chemistry is boring Chemistry is pollution Chemistry does not excite Chemistry is poison Chemistry is a finished subject Chemistry is dirty Chemistry - stands on the legacy of giants Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier (1743-1794) Marie Skłodowska Curie (1867- 1934) John Dalton (1766- 1844) Sir Humphrey Davy (1778 – 1829) Michael Faraday (1791 – 1867) Chemistry – our legacy Mendeleev's Periodic Table Modern Periodic Table Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev (1834-1907) Joseph John Thomson (1856 –1940) Great experimentalists Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937) Jagadish Chandra Bose (1858 –1937) Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman (1888-1970) Chemistry and chemical bond Gilbert Newton Lewis (1875 –1946) Harold Clayton Urey (1893- 1981) Glenn Theodore Seaborg (1912- 1999) Linus Carl Pauling (1901– 1994) Master craftsmen Robert Burns Woodward (1917 – 1979) Chemistry and the world Fritz Haber (1868 – 1934) Machines in science R. E. Smalley Great teachers Graduate students : Other students : 1. Werner Heisenberg 1. Herbert Kroemer 2. Wolfgang Pauli 2. Linus Pauling 3. Peter Debye 3. Walter Heitler 4. Paul Sophus Epstein 4. Walter Romberg 5. Hans Bethe 6. Ernst Guillemin 7. Karl Bechert 8. Paul Peter Ewald 9. Herbert Fröhlich 10. Erwin Fues 11. Helmut Hönl 12. Ludwig Hopf 13. Walther Kossel 14. -

Portraits from Our Past

M1634 History & Heritage 2016.indd 1 15/07/2016 10:32 Medics, Mechanics and Manchester Charting the history of the University Joseph Jordan’s Pine Street Marsden Street Manchester Mechanics’ School of Anatomy Medical School Medical School Institution (1814) (1824) (1829) (1824) Royal School of Chatham Street Owens Medicine and Surgery Medical School College (1836) (1850) (1851) Victoria University (1880) Victoria University of Manchester Technical School Manchester (1883) (1903) Manchester Municipal College of Technology (1918) Manchester College of Science and Technology (1956) University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (1966) e University of Manchester (2004) M1634 History & Heritage 2016.indd 2 15/07/2016 10:32 Contents Roots of the University 2 The University of Manchester coat of arms 8 Historic buildings of the University 10 Manchester pioneers 24 Nobel laureates 30 About University History and Heritage 34 History and heritage map 36 The city of Manchester helped shape the modern world. For over two centuries, industry, business and science have been central to its development. The University of Manchester, from its origins in workers’ education, medical schools and Owens College, has been a major part of that history. he University was the first and most Original plans for eminent of the civic universities, the Christie Library T furthering the frontiers of knowledge but included a bridge also contributing to the well-being of its region. linking it to the The many Nobel Prize winners in the sciences and John Owens Building. economics who have worked or studied here are complemented by outstanding achievements in the arts, social sciences, medicine, engineering, computing and radio astronomy. -

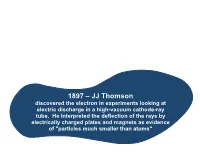

JJ Thomson Discovered the Electron in Experiments Looking At

1897 – JJ Thomson discovered the electron in experiments looking at electric discharge in a high-vacuum cathode-ray tube. He interpreted the deflection of the rays by electrically charged plates and magnets as evidence of "particles much smaller than atoms" 1896 – Henri Becquerel – Though fascinated by materials that exhibited phosphorescence, it was through experiments involving non-phosphorescent uranium salts that he gained his real notoriety. While experimenting with these materials, he discovered natural radioactivity. Through his experiment, he determined that the penetrating radiation came from the uranium itself, without any need of excitation by an external energy source. 1895 – Wilhelm Röentgen – During an experiment, he noticed photographic plates near his equipment glowing. He discovered the glowing was caused by rays emitted by the glass tube used in his investigation. This tube contained a pair of electrodes. As electricity passed between the electrodes, X‑rays were emitted and appeared on the photographic plates. 1887 – Svante Arrhenius ACID = neutral compound that ionizes when dissolved in water and produces the H+ ion and corresponding negative ion. BASE = neutral compound that either dissociates or ionizes in water to give OH- ions and a corresponding positive ion. 1806 - Gay-Lussac - Gay-Lussac's Law states that at constant volume, the pressure of a sample of gas is directly proportional to its temperature in Kelvin. He also provided us with the law of combining volumes - when gases react, the volumes consumed and produced, measured at the same temperature and pressure, are in ratios of small whole numbers. 1804 – John Dalton Once again contributed to the chemical world and gave us the Law of Multiple Proportions – If the same two elements form more than one compound between them, then the combining mass ratios of the two compounds will NOT be the same.