Housing Rent Dynamics and Rent Regulation in St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HSE University – St. Petersburg International Student Handbook 2018

HSE University St. Petersburg International Student Handbook 2018 HSE University – St. Petersburg International Student Handbook 2018 HSE University – St. Petersburg International Student Handbook HSE University – St. Petersburg Dear international student! Congratulations on your acceptance to HSE University – St. Petersburg! We are happy to welcome you here, and we hope that you will enjoy your stay in the beautiful city of St. Petersburg! This Handbook is intended to help you adapt to a new environment and cope with day to day activities. It contains answers to some essential questions that might arise during the first days of your stay. If you have questions that we have not covered here, feel free to contact us directly. We wish you success and many wonderful discoveries! Best regards, HSE University – St. Petersburg International Office team International Student Handbook 3 HSE University – St. Petersburg INTERNATIONAL OFFICE Address: rooms 331 and 322 at 3A Kantemirovskaya street, St. Petersburg, Russia 194100 Office hours: Monday – Friday from 10.00 am till 6.00 pm Website: spb.hse.ru/international Email: [email protected] Phone: +7 (812) 644 59 10 International Student Handbook 4 HSE University – St. Petersburg Olga Krylova Head of International Office Maria Vrublevskaya Konstantin Platonov Director of the Centre for International Education Director of the Centre for International Cooperation Dilyara Shaydullina Daria Zima Admission coordinator (Bachelor’s programmes) Academic mobility manager [email protected] [email protected] ext. 61583 ext. 61245 Viktoria Isaeva Anna Burdaeva Admission coordinator (Master’s programmes) Migration support manager [email protected] [email protected] ext. 61583 ext. 61577 Veronika Denisova Elena Kavina Short-term programmes coordinator Migration support manager [email protected] [email protected] ext. -

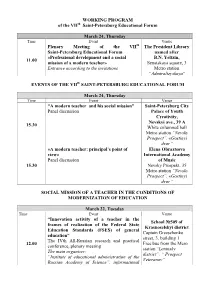

WORKING PROGRAM of the VII Saint-Petersburg Educational

WORKING PROGRAM of the VIIth Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue Plenary Meeting of the VIIth The President Library Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum named after «Professional development and a social B.N. Yeltzin, 11.00 mission of a modern teacher» Senatskaya square, 3 Entrance according to the invitations Metro station “Admiralteyskaya” EVENTS OF THE VIIth SAINT-PETERSBURG EDUCATIONAL FORUM March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue “A modern teacher and his social mission” Saint-Petersburg City Panel discussion Palace of Youth Creativity, Nevskyi ave., 39 A 15.30 White columned hall Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” «A modern teacher: principal’s point of Elena Obraztsova view» International Academy Panel discussion of Music 15.30 Nevsky Prospekt, 35 Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” SOCIAL MISSION OF A TEACHER IN THE CONDITIONS OF MODERNIZATION OF EDUCATION March 22, Tuesday Time Event Venue “Innovation activity of a teacher in the School №509 of frames of realization of the Federal State Krasnoselskyi district Education Standards (FSES) of general Captain Greeschenko education” street, 3, building 1 The IVth All-Russian research and practical 12.00 Free bus from the Mero conference, plenary meeting station “Leninsky The main organizer: district”, “ Prospect “Institute of educational administration of the Veteranov” Russian Academy of Science”, informational and methodological center of Krasnoselskyi district of Saint-Petersburg, School №509 of Krasnoselskyi district March -

Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984)

1 de 2 SCULPTOR NINA SLOBODINSKAYA (1898-1984). LIFE AND SEARCH OF CREATIVE BOUNDARIES IN THE SOVIET EPOCH Anastasia GNEZDILOVA Dipòsit legal: Gi. 2081-2016 http://hdl.handle.net/10803/334701 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ca Aquesta obra està subjecta a una llicència Creative Commons Reconeixement Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution licence TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898 -1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 Programa de doctorat: Ciències humanes I de la cultura Dirigida per: Dra. Maria-Josep Balsach i Peig Memòria presentada per optar al títol de doctora per la Universitat de Girona 1 2 Acknowledgments First of all I would like to thank my scientific tutor Maria-Josep Balsach I Peig, who inspired and encouraged me to work on subject which truly interested me, but I did not dare considering to work on it, although it was most actual, despite all seeming difficulties. Her invaluable support and wise and unfailing guiadance throughthout all work periods were crucial as returned hope and belief in proper forces in moments of despair and finally to bring my study to a conclusion. My research would not be realized without constant sacrifices, enormous patience, encouragement and understanding, moral support, good advices, and faith in me of all my family: my husband Daniel, my parents Andrey and Tamara, my ount Liubov, my children Iaroslav and Maria, my parents-in-law Francesc and Maria –Antonia, and my sister-in-law Silvia. -

Valuation Report PO-17/2015

Valuation Report PO-17/2015 A portfolio of real estate assets in St. Petersburg and Leningradskaya Oblast', Moscow and Moskovskaya Oblast’, Yekaterinburg, Russia Prepared on behalf of LSR Group OJSC Date of issue: March 17, 2016 Contact details LSR Group OJSC, 15-H, liter Ǩ, Kazanskaya St, St Petersburg, 190031, Russia Ludmila Fradina, Tel. +7 812 3856105, [email protected] Knight Frank Saint-Petersburg ZAO, Liter A, 3B Mayakovskogo St., St Petersburg, 191025, Russia Svetlana Shalaeva, Tel. +7 812 3632222, [email protected] Valuation report Ň A portfolio of real estate assets in St. Petersburg and Leningradskaya Oblast', Moscow and Moskovskaya Oblast’, Yekaterinburg, Russia Ň KF Ref: PO-17/2015 Ň Prepared on behalf of LSR Group OJSC Ň Date of issue: March 17, 2016 Page 1 Executive summary The executive summary below is to be used in conjunction with the valuation report to which it forms part and, is subject to the assumptions, caveats and bases of valuation stated herein. It should not be read in isolation. Location The Properties within the Portfolio of real estate assets to be valued are located in St. Petersburg and Leningradskaya Oblast', Moscow, Yekaterinburg, Russia Description The Subject Property is represented by vacant, partly or completely developed land plots intended for residential and commercial development and commercial office buildings with related land plots. Areas Ɣ Buildings – see the Schedule of Properties below Ɣ Land plots – see the Schedule of Properties below Tenure Ɣ Buildings – see the Schedule of Properties below Ɣ Land plots – see the Schedule of Properties below Tenancies As of the valuation date from the data provided by the Client, the office properties are partially occupied by the short-term leaseholders according to the lease agreements. -

Building the Revolution. Soviet Art and Architecture, 1915

Press Dossier ”la Caixa” Social Outreach Programmes discovers at CaixaForum Madrid the art and architecture from the 1920s and 30s Building the Revolution. Soviet Art and Architecture 1915-1935 The Soviet State that emerged from the 1917 Russian Revolution fostered a new visual language aimed at building a new society based on the socialist ideal. The decade and a half that followed the Revolution was a period of intense activity and innovation in the field of the arts, particularly amongst architects, marked by the use of pure geometric forms. The new State required new types of building, from commune houses, clubs and sports facilities for the victorious proletariat, factories and power stations in order to bring ambitious plans for industrialisation to fruition, and operations centres from which to implement State policy and to broadcast propaganda, as well as such outstanding monuments as Lenin’s Mausoleum. Building the Revolution. Soviet Art and Architecture 1915-1935 illustrates one of the most exceptional periods in the history of architecture and the visual arts, one that is reflected in the engagement of such constructivist artists as Lyubov Popova and Alexander Rodchenko and and Russian architects like Konstantin Melnikov, Moisei Ginzburg and Alexander Vesnin, as well as the European architects Le Corbusier and Mendelsohn. The exhibition features some 230 works, including models, artworks (paintings and drawings) and photographs, featuring both vintage prints from the 1920s and 30s and contemporary images by the British photographer Richard Pare. Building the Revolution. Soviet Art and Architecture 1915-1935 , is organised by the Royal Academy of Arts of London in cooperation with ”la Caixa” Social Outreach Programmes and the SMCA-Costakis Collection of Thessaloniki. -

ST. Petersburg

Hotels Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Events Maps ST. pETERSbuRg June - July 2013 parks and palaces Visit the former homes of the Tsars White Nights Rooftop terraces and summer festivals 16+ June - July 2013 No89 st_petersburg.inyourpocket.com CONTENTS 3 Restaurants 25 Russian, Italian, rooftop terraces and more ESSENTIAL CITY GUIDES Nightlife 38 Bars, pubs and clubs – how to stay out till 6 am Contents Sightseeing Foreword 4 The essentials 42 A word from our editor Hermitage 43 News 5 Shopping 48 What’s new in the city What to buy and where Basics and Language 6 Expat and Lifestyle 51 Some useful information Expat Experience, Religious Services and more Culture and Events 8 Getting around Ballet, opera, concerts and exhibitions Transport, tickets and more 53 Maps 54 Features St. Petersburg’s Historical Outskirts 15 Russia 58 Islands: Krestovsky and Yelagin 20 Moscow 59 Veliky Novgorod and Staraya Russa 61 Hotels 21 Kazan 64 A fine selection of places to spend the night Nizhny Novgorod 66 st_petersburg.inyourpocket.com June - July 2013 4 FOREWORD NEWS 5 It’s official now. Summer is here. After the ridiculously long winter we can now finally enjoy the famous white nights and Europe In Your Pocket Russia Day Summer in New Holland the magical midnight sun. We can attend amazing theatre The youngest of Russia’s many public holidays, Russia Day programmes and open-air festivals and go on boat tours is celebrated on the 12th of June. Originally it marked the around the canals and have cocktails on the city’s best Northern adoption of the new Russian constitution during the breaking rooftop terraces. -

Saint Petersburg

GUIDE SAINT PETERSBURG 2018 WELCOME TO SAINT PETERSBURG 2 SSAINTaint PETERSBURGPetersburg 3 Free ride for Fan ID football fans, FAN ID is a small volunteers and laminated form FIFA accredited with the holder’s guests in urban personal data. and suburban transport (except taxi). Also free of charge are electric trains that run on the routes between sports FAN ID and the match ticket are obligatory Addresses and opening events (including documents to show at the entrance hours of FAN ID collec- the metro) to a match. You should have had it tion points are beforehand. It is issued for free at www.fan-id.ru FAN ID and the match ticket al- low a free ride in transport in the FAN ID is a visa-free travel to cities and between them on the the Russian Federation as 2018 FIFA World Cup days well free of charge excursions and tourist routes 4 Russia 5 EXPECTATIONS Foreigners often think that the Kaliningrad everlasting winter and snow hills ST. Petersburg two meters high are Russia. Even COPENHAGEN EDINBURG in summer it’s freezing cold and +20 uncomfortable. May be there is no summer at all. Follow me! Moscow To be continued on the next Nizhniy Novgorod page. Saransk REALITY Kazan In fact in most parts of Russia summer is a warm Volgograd Rostov-on–Don Samara and nice season. By compari- Yekaterinburg son, Moscow summer is like Minne- Sochi apolis (the USA) summer, the summer weather in Saint Petersburg is just like the weather in summer Copenhagen (Denmark), the weather in Kazan in summer resembles the weather in Chinese Harbin. -

The Independent Turn in Soviet-Era Russian Poetry: How Dmitry Bobyshev, Joseph Brodsky, Anatoly Naiman and Evgeny Rein Became the ‘Avvakumites’ of Leningrad

The Independent Turn in Soviet-Era Russian Poetry: How Dmitry Bobyshev, Joseph Brodsky, Anatoly Naiman and Evgeny Rein Became the ‘Avvakumites’ of Leningrad. Margo Shohl Rosen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Margo Shohl Rosen All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Independent Turn in Soviet-Era Russian Poetry: How Dmitry Bobyshev, Joseph Brodsky, Anatoly Naiman and Evgeny Rein Became the ‘Avvakumites’ of Leningrad Margo Shohl Rosen The first post-World War II generation of Soviet Russian writers was faced with a crisis of language even more pervasive and serious than the “Crisis of Symbolism” at the beginning of the 20th century: the level of abstraction and formulaic speech used in public venues had become such that words and phrases could only gesture helplessly in the direction of mysterious meaning. Due to the traditional status of poetry in Russian culture and to various other factors explored in this dissertation, the generation of poets coming of age in the mid-1950s was in a unique position to spearhead a renewal of language. Among those who took up the challenge was a group of four friends in Leningrad: Dmitry Bobyshev, Joseph Brodsky, Anatoly Naiman, and Evgeny Rein. Because of the extreme position this group adopted regarding the use of language, I refer to them in this work not as “Akhmatova’s Orphans”—a term commonly applied to the quartet—but as literary “Avvakumites,” a name Anna Akhmatova suggested that invokes the history of Archpriest Avvakum, who by rejecting reforms in church ritual founded the Orthodox sect now known as Old Believers. -

2016 – 21St Youth Bios Olympiad

Organizers Biopolitics International Organisation RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES SAINT-PETERSBURG * 10 Tim. Vassou, 115 21 Athens, Greece. RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES SCIENTIFIC CENTER SAINT-PETERSBURG SCIENTIFIC CENTER Теl.: (+30) 210 643-24-19, * Fax: (+30) 210 643-40-93 SAINT-PETERSBURG SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH CENTER FOR e-mail: [email protected] ECOLOGICAL SAFETY RAS * web-site: www.biopolitics.gr BIOPOLITICS INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATION * ADMINISTRATION OF SAINT PETERSBURG St. Petersburg scientific center COMMITTEE ON EXTERNAL RELATIONS Russian Academy of Sciences * PETER THE GREAT ST.PETERSBURG POLYTECHNIC ADMINISTRATION OF SAINT PETERSBURG 199034, Saint-Petersburg, UNIVERSITY THE COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE AND THE HIGHER SCHOOL * Universitetskaya nab. 5, ST. PETERSBURG ADMINISTRATIONS tel/fax: 8(812) 323-30-25 OF EDUCATION COMMITTEE e-mail: [email protected] ADMINISTRATION OF SAINT PETERSBURG web-site: http://www.spbrc.nw.ru/ THE COMMITTEE ON YOUTH POLICY AND INTERACTION WITH PUBLIC ORGANIZATIONS * Saint–Petersburg State Polytechnical ADMINISTRATION OF SAINT–PETERSBURG COMMITTEE ON NATURE USE, ENVIRONMENTAL University Peter the Great PROTECTION AND ECOLOGICAL SAFETY 199034, Saint-Petersburg, Polytechnical, 29 * (m. Polytechnical) ADMINISTRATION OF LENINGRAD REGION BIOPOLITICS INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATION THE COMMITTEE ON YOUTH POLICY tel/fax: 8(812) 552-60-80 AND INTERACTION WITH PUBIC ORGANIZATIONS e-mail: [email protected] INTERREGIONAL ECOLOGICAL CLUB * GRADUATE STUDENTS, STUDENTS AND ADMINISTRATION OF LENINGRAD REGION web-site: http://www.spbstu.ru -

The Underground Tour. the Plans to Build the Subway First Appeared As Early As 1820S, but They Were Dismissed by Alexander I

The underground tour. The plans to build the subway first appeared as early as 1820s, but they were dismissed by Alexander I. The issue was raised again in the early 20th century but it was soon dropped due to beginning of the First World War. The decision to build the subway was made in January 1941, but due to the Second World War the actual construction began just in 1950s. Some of the tunnels were ready though and served as dry and cool storage for the bodies of those starved to death during the Siege of Leningrad. Interesting facts about our subway: The average daily distance traveled by a passenger is 11 km. The average speed is 35-40 km/h and the maximum speed is 90 km/h. St.Petersburg’s subway, with the average depth of 57 metres, is the deepest in the world. Admiralteyskaya station with its 102 meters is the deepest station in Russia. It was the most northern subway until Helsinki opened its subway in 1982. To build a subway in Leningrad was a serious engineering challenge due to unstable soil, ground water, unknown underground rivers and streams, boulders left by the ice age and the depth of the Neva. There were three churches that had to be destroyed in order to build more stations: the Church of the Holy Sign, the Savior on Haymarket (Sennaya), and Cosmo and Damien. Ploshad Vosstania, Sennaya and Chernyshevskaya ground pavilions were built instead. Red Line The longest (almost 30km) and oldest line built in 1955 for transporting workers to the Kirov plant famous for it’s tractors. -

Copyrighted Material

176 Hermitage, 3, 4, 9, C 26–37 Caberet (club), 128 Index Isaac Brodsky Carnivals, 106 Index See also Accommoda- Museum, 42 Car rentals, 165, 166 tions and Restaurant Marble Palace, 19 Cashpoints, 168 Museum of the Imperial indexes, below. Cathedral of Our Lady of Porcelain Factory, 31 Kazan, 3, 11 Russian Museum, 15–17 Cathedral of St Peter & A State Photography St Paul, 64 Achtung Baby (club), 127 Centre, 73–74 Catherine I, 18, 65 Adamson. A. G., 12 Stieglitz Museum of Catherine II, 10, 29, 32, 59, Admiralty, 9 Applied Arts, 18 65, 76 Air travel, 166–167 trophy art in, 36–37 Catherine (Ekaterininsky) Akhamatova, Anna, 47 Artillery Museum, 22, 63, 67 Palace, 157–159 Akhamatova Museums, 47 Art Market, 98a Caucasian dishes, 114 Alexander Column, 9 A.S. Popov Central Museum Cellphones, 165 Alexander Hall (Hermi- of Communications, 75 Central Naval Museum, 81 tage), 28 ATMs, 168 Central School of Design, 18 Alexander II, 8, 39, 73, 172 Avrora Cinema, 136 Central Station (club), 128 Alexander Nevsky Monas- Avrora (Aurora) cruiser, Chainy Dom, 77, 120, 125 tery, 3, 12–13, 53–54 22, 41, 43 Chernaya Rechka, 45 Alexander Palace, 157 Avtovo (metro station), 23 Chesme Church, 4, 61 Alexandrinsky Theatre, 77 Chesme Palace, 61 Alexandrovsky Lycee, 42 B Chet Poberi!, 120, 126 Aliye Parusa (Red Sails), Ballet, 130, 134–135 Children, activities for 4, 24, 165 Banya, 130, 135 amusement parks, 106 All-Union Leninist Communist Bars, 120, 125–127 in the Hermitage, 35 Youth League Park, 85 B&Bs, 149, 168 military museums, Amber Room (Tsarskoye Beloselsky-Belozersky -

Eu-Russia Regional Cooperation and Energy Networks in the Russian Northwestern and Southern Regions: Implications for Democratic Governance

EU-RUSSIA REGIONAL COOPERATION AND ENERGY NETWORKS IN THE RUSSIAN NORTHWESTERN AND SOUTHERN REGIONS: IMPLICATIONS FOR DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE by Ekaterina Turkina BA, Ryazan State University, 2002 MPIA, University of Pittsburgh, 2006 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2009 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH GRADUATE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS This dissertation was presented by Ekaterina Turkina It was defended on April 21, 2009 and approved by Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Martin Staniland, Professor, GSPIA, University of Pittsburgh Dissertation Co-Chair: Dr. Louise Comfort, Professor, GSPIA, University of Pittsburgh Dr. Alberta Sbragia, Professor and Jean Monnet Chair ad personam, Political Science, University of Pittsburgh Dr. Louis Picard, Professor, GSPIA, University of Pittsburgh ii EU-RUSSIA REGIONAL COOPERATION AND ENERGY NETWORKS IN THE RUSSIAN NORTHWESTERN AND SOUTHERN REGIONS: IMPLICATIONS FOR DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE Ekaterina Turkina, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2009 This dissertation seeks to explain variation in democratic governance in the Russian Federation, in particular, difference in the levels of democratic governance between the northwestern and the southern regions of Russia that are included in the regional dimensions of the European Union foreign policy: the Northern Dimension and the Black Sea Synergy, respectively. Emphasizing a dynamic relationship among regional governance