Marcelline Hutton [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Deep Purple Tributes

[% META title = 'The Deep Purple Discography' %] The Deep Purple Tributes Here we will try to keep a list of known Deep Purple tributes -- full CDs only. (Covers of individual tracks are listed elsewhere.) The list is still not complete, but hopefully it will be in the future. Funky Junction Plays a Tribute to Deep Purple UK 1973 Stereo Gold Award MER 373 [1LP] Purple Tracks Performed by Eric Bell (guitar), Brian Downey (drums), Dave Lennox (keyboards), Phil Lynott (bass) and Fireball Black Night Benny White (vocals). Strange Kind of Woman Hush Speed King The first known Purple tribute was recorded as early as 1972. An unknown, starving band named Thin Lizzy (which consisted of Bell, Downey & Lynott) were offered a lump sum of money to record some Deep Purple songs. (The album contains also a few non-DP tracks.) They did - with the help from two Irish guys. The album came out in early 1973. It wasn't a success. In February, Thin Lizzy had a top ten hit with a single of their own. Read more about it here. The Moscow Symphony Orchestra in Performance of the Music of Deep Purple Japan 1992 Zero Records XRCN-1022 [1CD] UK 1992 Cromwell Productions CPCD 018 [1CD] Purple Tracks Smoke on the Water Performed by the Moscow Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Constantine Krimets. Arranged by Stephen Space Truckin' Child in Time Reeve and Martin Riley. Produced by Bob Carruthers. Recorded live (in the studio with no audience) during Black Night April 1992. Lazy The Mule Pictures of Home No drums, no drum machine, no guitar - in fact, no rock instruments at all, just a symphony orchestra. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

HSE University – St. Petersburg International Student Handbook 2018

HSE University St. Petersburg International Student Handbook 2018 HSE University – St. Petersburg International Student Handbook 2018 HSE University – St. Petersburg International Student Handbook HSE University – St. Petersburg Dear international student! Congratulations on your acceptance to HSE University – St. Petersburg! We are happy to welcome you here, and we hope that you will enjoy your stay in the beautiful city of St. Petersburg! This Handbook is intended to help you adapt to a new environment and cope with day to day activities. It contains answers to some essential questions that might arise during the first days of your stay. If you have questions that we have not covered here, feel free to contact us directly. We wish you success and many wonderful discoveries! Best regards, HSE University – St. Petersburg International Office team International Student Handbook 3 HSE University – St. Petersburg INTERNATIONAL OFFICE Address: rooms 331 and 322 at 3A Kantemirovskaya street, St. Petersburg, Russia 194100 Office hours: Monday – Friday from 10.00 am till 6.00 pm Website: spb.hse.ru/international Email: [email protected] Phone: +7 (812) 644 59 10 International Student Handbook 4 HSE University – St. Petersburg Olga Krylova Head of International Office Maria Vrublevskaya Konstantin Platonov Director of the Centre for International Education Director of the Centre for International Cooperation Dilyara Shaydullina Daria Zima Admission coordinator (Bachelor’s programmes) Academic mobility manager [email protected] [email protected] ext. 61583 ext. 61245 Viktoria Isaeva Anna Burdaeva Admission coordinator (Master’s programmes) Migration support manager [email protected] [email protected] ext. 61583 ext. 61577 Veronika Denisova Elena Kavina Short-term programmes coordinator Migration support manager [email protected] [email protected] ext. -

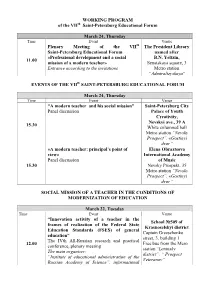

WORKING PROGRAM of the VII Saint-Petersburg Educational

WORKING PROGRAM of the VIIth Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue Plenary Meeting of the VIIth The President Library Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum named after «Professional development and a social B.N. Yeltzin, 11.00 mission of a modern teacher» Senatskaya square, 3 Entrance according to the invitations Metro station “Admiralteyskaya” EVENTS OF THE VIIth SAINT-PETERSBURG EDUCATIONAL FORUM March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue “A modern teacher and his social mission” Saint-Petersburg City Panel discussion Palace of Youth Creativity, Nevskyi ave., 39 A 15.30 White columned hall Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” «A modern teacher: principal’s point of Elena Obraztsova view» International Academy Panel discussion of Music 15.30 Nevsky Prospekt, 35 Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” SOCIAL MISSION OF A TEACHER IN THE CONDITIONS OF MODERNIZATION OF EDUCATION March 22, Tuesday Time Event Venue “Innovation activity of a teacher in the School №509 of frames of realization of the Federal State Krasnoselskyi district Education Standards (FSES) of general Captain Greeschenko education” street, 3, building 1 The IVth All-Russian research and practical 12.00 Free bus from the Mero conference, plenary meeting station “Leninsky The main organizer: district”, “ Prospect “Institute of educational administration of the Veteranov” Russian Academy of Science”, informational and methodological center of Krasnoselskyi district of Saint-Petersburg, School №509 of Krasnoselskyi district March -

Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984)

1 de 2 SCULPTOR NINA SLOBODINSKAYA (1898-1984). LIFE AND SEARCH OF CREATIVE BOUNDARIES IN THE SOVIET EPOCH Anastasia GNEZDILOVA Dipòsit legal: Gi. 2081-2016 http://hdl.handle.net/10803/334701 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ca Aquesta obra està subjecta a una llicència Creative Commons Reconeixement Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution licence TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898 -1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 Programa de doctorat: Ciències humanes I de la cultura Dirigida per: Dra. Maria-Josep Balsach i Peig Memòria presentada per optar al títol de doctora per la Universitat de Girona 1 2 Acknowledgments First of all I would like to thank my scientific tutor Maria-Josep Balsach I Peig, who inspired and encouraged me to work on subject which truly interested me, but I did not dare considering to work on it, although it was most actual, despite all seeming difficulties. Her invaluable support and wise and unfailing guiadance throughthout all work periods were crucial as returned hope and belief in proper forces in moments of despair and finally to bring my study to a conclusion. My research would not be realized without constant sacrifices, enormous patience, encouragement and understanding, moral support, good advices, and faith in me of all my family: my husband Daniel, my parents Andrey and Tamara, my ount Liubov, my children Iaroslav and Maria, my parents-in-law Francesc and Maria –Antonia, and my sister-in-law Silvia. -

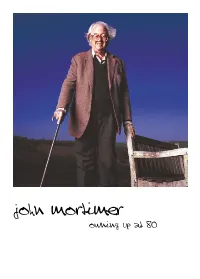

Imagine... John Mortimer

john mortimer owning up at 80 john mortimer owning up at 80 In the year he celebrates his 80th birthday, John Mortimer, the barrister turned author who became a household name with the creation of his popular drama Rumpole of the Bailey, is about to publish his latest book, Where There’s a Will. Imagine captures him pondering on life and offering advice to his children, grandchildren and in his own words “anyone who’ll listen”. John Mortimer’s wit and love of life shines through in this reflection on his life and career.The film eavesdrops on his 80th birthday celebrations, visits his childhood home – where he still lives today – and goes to his old law chambers.There are interviews with the people who know him best, including Richard Eyre, Jeremy Paxman, Kathy Lette, Leslie Phillips and Geoffrey Robertson QC. Imagine looks at the extraordinary influence Mortimer has had on the legal system in the UK.As a civil rights campaigner and defender par excellence in some of the most high-profile, inflammatory trials ever in the UK – such as the Oz trial and the Gay News case – he brought about fundamental changes at the heart of British law. His experience in the courts informs all of Mortimer’s writing, from plays, novels and articles to the infamous Rumpole of the Bailey, whose central character became a compelling mouthpiece for Mortimer’s liberal political views. Imagine looks at the great man of law, political campaigner, wit, gentleman, actor, ladies’ man and champagne socialist who captured the hearts of the British public.. -

A Fringe of Leaves”

Cicero, Karina R. Time and language in Patrick White's “A fringe of leaves” Tesis de Licenciatura en Lengua y Literatura Inglesa Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la Institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Cicero, Karina R. “Time and language in Patrick White's A fringe of leaves” [en línea]. Tesis de Licenciatura. Universidad Católica Argentina. Facultad de Filosofía y Letras. Departamento de Lenguas, 2010. Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/tesis/time-and-language-patrick-white.pdf [Fecha de Consulta:.........] (Se recomienda indicar fecha de consulta al final de la cita. Ej: [Fecha de consulta: 19 de agosto de 2010]). Universidad Católica Argentina Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Departamento de Lenguas “Time and Language in Patrick White’s A Fringe of Leaves. ” Student: Karina R. Cicero Tutor: Dr. Malvina I. Aparicio Tesis de Licenciatura Noviembre, 2010 1 Introduction A Fringe of Leaves starts, just like two of the most significant events in Australian history - colonisation and immigration- with a journey across the sea. Journeys often entail changes in one’s personality. Sometimes, radical ones. Travellers have always ventured to meet the unexpected in order to find answers to unasked questions having as a consequence a different approach to existence. In A Fringe of Leaves (1976), written by 1973 Nobel Prize- winner Patrick White, the character of Ellen Roxburgh assesses her whole existence through the hardships she faces during her journey to and within Australia. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Professor Robert Beveridge FRSA, University of Sassari

Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Relations Committee Scotland’s Screen Sector Written submission from Professor Robert Beveridge FRSA, University of Sassari 1. Introduction While it is important that the Scottish Parliament continues to investigate and monitor the state of the creative and screen industries in Scotland, the time has surely come for action rather than continued deliberation(s) The time has surely come when we need to stop having endless working parties and spending money on consultants trying to work out what to do. Remember the ‘Yes Minister’ Law of Inverse Relevance ‘ ‘The less you intend to do about something, the more you have to keep talking about it ‘ ‘Yes Minister’ Episode 1: Open Government Therefore, please note that we already know what to do. That is: 1.1 - Appoint the right people with the vision leadership and energy to succeed. 1.2 - Provide a positive legislative/strategic/policy framework for support. 1.3 - Provide better budgets and funding for investment and/or leverage for the same. (You already have access to the data on existing funding for projects and programmes of all kinds. If the Scottish Government wishes to help to improve performance in the screen sector, there will need to be a step change in investment. There is widespread agreement that more is needed.) 1.4 Give them space to get on with it. That is what happened with the National Theatre of Scotland. This is what happened with MG Alba. Both signal success stories. Do likewise with the Screen Industries in Scotland 2. Context Some ten years ago the Scottish Government established the Scottish Broadcasting Commission. -

The Nebraska Transcript, Spring 2016, Vol. 49 No.1

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The eN braska Transcript Law, College of Spring 2016 The eN braska Transcript, Spring 2016, Vol. 49 No.1 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebtranscript Part of the Law Commons "The eN braska Transcript, Spring 2016, Vol. 49 No.1" (2016). The Nebraska Transcript. 21. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebtranscript/21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The eN braska Transcript by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Nebraska RANSCRIPT T University of Nebraska College of Law Former Dean Susan Poser begins new chapter at UIC Also in this issue: Works, Kirst and Lyons retire with combined 123 years of service Pittman appointed to top position in The United Nations Spring 2016, Vol. 49 No. 1 Nebraska Law Table of Contents Spring 2016, Vol. 49 No.1 Dean’s Message 2 Dean’s Message Faculty Updates 4 Works, Kirst & Lyons retirement 6 Faculty Notes Around the College 17 Moberly appointed interim dean 18 Berger, assoicate dean 18 Sullivan joins Law College 19 Beard & Hurwitz named Trailblazers Feature 20 Poser closes UNL chapter Around the College 23 3L gains policy work experience 24 ILSA hosts USPTO’s Morris 25 West African leaders share insight 26 McCoy joins admissions office 27 BYC Boost program 28 Collingsworth, Dean’s roundtable 29 Yale’s Langbein delivers lecture 30 Heiliger, Sheldon at UNK 31 Vinton competes on Jeopardy 32 LL.M., Carns earns promotion 32 Law Team wins Ag Law Quiz Bowl 34 December 2015 commencement Poser ends deanship, service at UNL Our Alumni Susan Poser concluded her time as dean of the College of Law on 36 Curtiss visits Entreprenuership Clinic January 27, 2016, to join the University of Illinois-Chicago as its 37 Pittman promoted to head of chamber provost and senior vice chancellor for academic affairs. -

Chancellor Search

University of Nebraska–Lincoln CHANCELLOR SEARCH October 2015 Contents University of Nebraska-Lincoln Chancellor Profile Appendix AN INVITATION FOR NOMINATIONS & APPLICATIONS 3 UNIVERSITY LEADERSHIP Organizational Framework 4 University Board of Regents and President 16 About the University of Nebraska-Lincoln 5 Campus Leadership Organization Chart 17 UNL’s Fundamental Missions 5 UNL OVERVIEW Student Life and Athletics 7 Husker Athletics 18 Role of the Chancellor 8 Nebraska Innovation Campus 18 Key Opportunities and Challenges for the Next Chancellor 8 Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources 19 Qualifications and Experience 11 Nebraska College of Technical Agriculture 19 Location 13 College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources 20 The Search Advisory Committee 13 College of Architecture 20 The Search Process 14 College of Arts and Sciences 20 Nebraska Public Records 15 College of Business Administration 20 College of Education and Human Sciences 21 College of Engineering 21 Hixson-Lied College of Fine and Performing Arts 21 College of Journalism and Mass Communications 21 College of Law 22 Office of Graduate Studies 22 University Libraries 22 UNIVERSITY-WIDE INSTITUTES Robert B. Daugherty Water for Food Institute 22 National Strategic Research Institute 23 Buffett Early Childhood Institute 23 Rural Futures Institute 23 Peter Kiewit Institute 23 AFFILIATED ENTITIES Nebraska Alumni Association 24 Lied Center for Performing Arts 24 Nebraska Educational Telecommunications 24 International Quilt Study Center and Museum 24 Mary Riepma Ross Media Arts Center 25 Sheldon Museum of Art 25 University of Nebraska State Museum 25 University of Nebraska Press 25 University of Nebraska Foundation 26 | 2 | University of Nebraska-Lincoln Chancellor Profile Search for the Chancellor An Invitation for Nominations and Applications University of Nebraska President Hank Bounds invites nominations and applications for the position of chancellor of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln (UNL). -

Tour Pack Alfred Jarry’S Ubu Roi in Object Theatre

THÉÂTRE DE LA PIRE ESPÈCE (CANADA) PRESENTS ADAPTATION FROM TOUR PACK ALFRED JARRY’S UBU ROI IN OBJECT THEATRE www.pire-espece.com UBU ON THE TABLE THE WORLD’S GROTESQUENESS ON A TABLE! or What Happens When a Power-Hungry Vinegar Bottle, Hammer and Sugar Bowl Fight for the Throne. Two armies of French baguettes face each other in a stand-off as tomato bombs explode, an egg beater hovers over fleeing troops and molasses-blood splatters on fork-soldiers as they charge Père Ubu. Anything goes as Poland’s fate is sealed on a tabletop! Multiple film references spice things up as two performers hammer-out a small-scale fresco of grandiose buffoonery. UBU IN OBJECT THEATRE Ubu is undeniably comfortable surrounded by kitchen utensils that double as gorging tools and weapons to annihilate the “sagouins”. The banality of the objects dramatically underscores the grotesque nature of the characters: Captain Bordure, embodied by a standard hammer, is forever stuck in his rigid stance, forced to repeat the same ridiculous expressions over and over. The Object’s expressive limits force the creators to focus on the dramatic action rather than on the psychological development of the characters. The actor-puppeteers (in full view) appeal to the audience’s intelligence and imagination by conveying a second degree to the storyline. OVER 900 PERFORMANCES This adaptation of Ubu Roi has garnered much praise – the objects’ raw form and the performance’s frenetic pace are perfectly suited for Alfred Jarry’s cruel farce. Since its creation, the show has been performed over 900 times in 15 COUNTRIES (Canada, France, Germany, U.K, Ireland, Mexico, Spain, Brazil, Bulgaria, Romania, Russia, Belgium, Turkey, Cuba, Finland).