The Ptolemies Versus the Achaean and Aetolian Leagues in the 250S–220S Bc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

Nabis and Flamininus on the Argive Revolutions of 198 and 197 B.C. , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 28:2 (1987:Summer) P.213

ECKSTEIN, A. M., Nabis and Flamininus on the Argive Revolutions of 198 and 197 B.C. , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 28:2 (1987:Summer) p.213 Nabis and Flamininus on the Argive Revolutions of 198 and 197 B.C. A. M. Eckstein N THE SUMMER of 19 5 a. c. T. Quinctius Flamininus and the Greek I allies of Rome went to war against N abis of Sparta. The official cause of the war was Nabis' continued occupation of Argos, the great city of the northeastern Peloponnese. 1 A strong case can be made that the liberation of Argos was indeed the crucial and sincere goal of the war,2 although the reasons for demanding Nabis' with drawal from Argos may have been somewhat more complex.3 Nabis was soon blockaded in Sparta itself and decided to open negotiations for peace. Livy 34.3lfprovides us with a detailed account of the sub sequent encounter between N abis and Flamininus in the form of a debate over the justice of the war, characterized by contradictory assertions about the history of Sparta's relations with Rome and the recent history of Argos. Despite the acrimony, a preliminary peace agreement was reached but was soon overturned by popular resis tance to it in Sparta. So the war continued, with an eventual Roman 1 Cf. esp. Liv. 34.22.10-12, 24.4, 32.4f. 2 See now E. S. GRUEN, The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome II (Berkeley/Los Angeles [hereafter 'Gruen']) 450-55, who finds the propaganda of this war, with its consistent emphasis on the liberation of Argos as a matter of honor both for Rome and for Flamininus, likely to have some basis in fact. -

Ig V 1, 16 and the Gerousia of Roman Sparta

IG V 1, 16 AND THE GEROUSIA OF ROMAN SPARTA (PLATE 46) G Vi 1,16 is embeddedupside down in the apseof the Katholikonin the monasteryof hJI[ the Agioi Saranta,the Forty Martyrsof Sebaste,some nine kilometerseast of Sparta.1Kolbe, the editor of the Laconian section of the corpus, based his edition on tran- scriptionsof the text in the works of antiquariantravelers, among them Col. William Leake and Ludwig Ross. Although the inscription, thanks to a restorationAdolf Wilhelm pro- posed and Kolbe adopted, is directly relevant to the vexatious problem of the size of the Spartan gerousia in the Roman period, no one has examined the stone since the 19th cen- tury.2A new edition based on autopsy is required. p. ante vel p. post A.D. 61 NON-ITOIX. Height 0.205 m. Width 0.277 m. Letter height 0.01 1-0.01 9 m. COL. I [o betva--------office ------------------------------------?IN]I ~[pwvosvJKAavbliov Katoapos----------------------------------]OIO I-----------------------------------------------------]II[--] ?-- 5 [--------------------------------------------------------- ?I] ?I] ?I] COL. II vacat Iro b Aou,oi j cvavo[ov? -?----------------------------------- SOY aL'-rcZoat.vacat [ vacat ] Aztarovtrov -rovi KocaAalov[ --------------------------------------[ rovtrovsyap o Aev 1c8ao[rs0] ------------------------------------? I An earlier version of this article was given as the paper "FortySaints, But How Many Gerontes?"at the 1989 annual meeting of the ArchaeologicalInstitute of America in Boston, Massachusetts. I would like to thank this journal's referees for their useful comments. Works frequently cited are abbreviatedas follows: Cartledgeand = P. Cartledge and A. Spawforth, Hellenistic and Roman Sparta. A Tale of Two Cities, Spawforth London 1989 Oliver = J. H. Oliver, GreekConstitutions of Early Roman Emperorsfrom Inscriptionsand Papy- ri, Philadelphia 1989 Kennell = N. -

Innovamass 240S/241S Manual

InnovaMass 240S/241S Instruction Manual Table of Contents 240/241 Series Vortex Volumetric and Mass Flow Meters Models: 240-V, VT, VTP, LP / 241-V, VT, VTP, LP, Cryogenic Instruction Manual Document Number IM-240 Revision: Q 6/20 IM-240 0-1 Table of Contents InnovaMass 240S/241S Instruction Manual GLOBAL SUPPORT LOCATIONS: WE ARE HERE TO HELP! CORPORATE HEADQUARTERS 5 Harris Court, Building L Monterey, CA 93940 Phone (831) 373-0200 (800) 866-0200 Fax (831) 373-4402 www.sierrainstruments.com EUROPE HEADQUARTERS Bijlmansweid 2 1934RE Egmond aan den Hoef The Netherlands Phone +31 72 5071400 Fax +31 72 5071401 ASIA HEADQUARTERS Second Floor Building 5 Senpu Industrial park 25 Hangdu Road Hangtou Town Pu Dong New District Shanghai, P.R. China Post Code 201316 Phone: 8621 5879 8521 Fax: 8621 5879 8586 Important Customer Notice for Oxygen Service Unless you have specifically ordered Sierra’s optional O2 cleaning, this flow meter may not be fit for oxygen service. Some models can only be properly cleaned during the manufacturing process. Sierra Instruments, Inc. is not liable for any damage or personal injury, whatsoever, resulting from the use of Sierra Instruments standard mass flow meters for oxygen gas. Specific Conditions of Use(ATEX/IECEx) Contact Manufacturer regarding Flame path information. Clean with a damp cloth to avoid any build-up of electrostatic charge. The model 240S and 241S Multivariable Mass Vortex Flowmeters standard temperature option (ST) process temperature range is -40°C to 260°C. The high temperature option (HT) process temperature range is -40°C up to +400°C. -

The Antigonids and the Ruler Cult. Global and Local Perspectives?

The Antigonids and the Ruler Cult Global and Local Perspectives? 1 Franca Landucci DOI – 10.7358/erga-2016-002-land AbsTRACT – Demetrius Poliorketes is considered by modern scholars the true founder of ruler cult. In particular the Athenians attributed him several divine honors between 307 and 290 BC. The ancient authors in general consider these honors in a negative perspec- tive, while offering words of appreciation about an ideal sovereignty intended as a glorious form of servitude and embodied in Antigonus Gonatas, Demetrius Poliorketes’ son and heir. An analysis of the epigraphic evidences referring to this king leads to the conclusion that Antigonus Gonatas did not officially encourage the worship towards himself. KEYWORDS – Antigonids, Antigonus Gonatas, Demetrius Poliorketes, Hellenism, ruler cult. Antigonidi, Antigono Gonata, culto del sovrano, Demetrio Poliorcete, ellenismo. Modern scholars consider Demetrius Poliorketes the true founder of ruler cult due to the impressively vast literary tradition on the divine honours bestowed upon this historical figure, especially by Athens, between the late fourth and the early third century BC 2. As evidenced also in modern bib- liography, these honours seem to climax in the celebration of Poliorketes as deus praesens in the well-known ithyphallus dedicated to him by the Athenians around 290 3. Documentation is however pervaded by a tone that is strongly hostile to the granting of such honours. Furthermore, despite the fact that it has been handed down to us through Roman Imperial writers like Diodorus, Plutarch and Athenaeus, the tradition reflects a tendency contemporary to the age of the Diadochi, since these same authors refer, often explicitly, to a 1 All dates are BC, unless otherwise stated. -

Copyrighted Material

9781405129992_6_ind.qxd 16/06/2009 12:11 Page 203 Index Acanthus, 130 Aetolian League, 162, 163, 166, Acarnanians, 137 178, 179 Achaea/Achaean(s), 31–2, 79, 123, Agamemnon, 51 160, 177 Agasicles (king of Sparta), 95 Achaean League: Agis IV and, agathoergoi, 174 166; as ally of Rome, 178–9; Age grades: see names of individual Cleomenes III and, 175; invasion grades of Laconia by, 177; Nabis and, Agesilaus (ephor), 166 178; as protector of perioecic Agesilaus II (king of Sparta), cities, 179; Sparta’s membership 135–47; at battle of Mantinea in, 15, 111, 179, 181–2 (362 B.C.E.), 146; campaign of, in Achaean War, 182 Asia Minor, 132–3, 136; capture acropolis, 130, 187–8, 192, 193, of Phlius by, 138; citizen training 194; see also Athena Chalcioecus, system and, 135; conspiracies sanctuary of after battle of Leuctra and, 144–5, Acrotatus (king of Sparta), 163, 158; conspiracy of Cinadon 164 and, 135–6; death of, 147; Acrotatus, 161 Epaminondas and, 142–3; Actium, battle of, 184 execution of women by, 168; Aegaleus, Mount, 65 foreign policy of, 132, 139–40, Aegiae (Laconian), 91 146–7; gift of, 101; helots and, Aegimius, 22 84; in Boeotia, 141; in Thessaly, Aegina (island)/Aeginetans: Delian 136; influence of, at Sparta, 142; League and,COPYRIGHTED 117; Lysander and, lameness MATERIAL of, 135; lance of, 189; 127, 129; pro-Persian party on, Life of, by Plutarch, 17; Lysander 59, 60; refugees from, 89 and, 12, 132–3; as mercenary, Aegospotami, battle of, 128, 130 146, 147; Phoebidas affair and, Aeimnestos, 69 102, 139; Spartan politics and, Aeolians, -

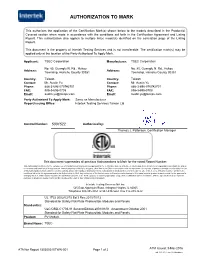

Authorization to Mark

AUTHORIZATION TO MARK This authorizes the application of the Certification Mark(s) shown below to the models described in the Product(s) Covered section when made in accordance with the conditions set forth in the Certification Agreement and Listing Report. This authorization also applies to multiple listee model(s) identified on the correlation page of the Listing Report. This document is the property of Intertek Testing Services and is not transferable. The certification mark(s) may be applied only at the location of the Party Authorized To Apply Mark. Applicant: TSEC Corporation Manufacturer: TSEC Corporation No. 85, Guangfu N. Rd., Hukou No. 85, Guangfu N. Rd., Hukou Address: Address: Township, Hsinchu County 30351 Township, Hsinchu County 30351 Country: Taiwan Country: Taiwan Contact: Mr. Austin Yu Contact: Mr. Austin Yu Phone: 886-3-696-0707#2701 Phone: 886-3-696-0707#2701 FAX: 886-3-696-0708 FAX: 886-3-696-0708 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Party Authorized To Apply Mark: Same as Manufacturer Report Issuing Office: Intertek Testing Services Taiwan Ltd. Control Number: 5001522 Authorized by: Thomas J. Patterson, Certification Manager This document supersedes all previous Authorizations to Mark for the noted Report Number. This Authorization to Mark is for the exclusive use of Intertek's Client and is provided pursuant to the Certification agreement between Intertek and its Client. Intertek's responsibility and liability are limited to the terms and conditions of the agreement. Intertek assumes no liability to any party, other than to the Client in accordance with the agreement, for any loss, expense or damage occasioned by the use of this Authorization to Mark. -

Spies (Kataskopoi, Otakoustai)

ch3.qxd 10/18/1999 2:12 PM Page 103 Chapter 3 Beyond the Pale: Spies (Kataskopoi, Otakoustai) It is almost as dif‹cult to de‹ne a spy as to catch one. The most common word among the Greeks for spies was kataskopoi, but throughout the classical era they did not use this term for spies alone: an author might employ it in one context where we would say “spy,” in another where we would understand “scout,” in a third where we would have dif‹culty translating it at all.1 Otakoustai were consistently used as covert agents, but they were rarely sent abroad.2 Is it then anachronistic to distinguish spies from other agents? The answer to this problem can perhaps be found in a distinction in the social perception of different types of kataskopoi (et al.). Some kataskopoi (i.e., spies) were perceived by their victims as treacherous and seem to have been subject to legislation concerning treachery; others (i.e., scouts et al.) were not.3 Whereas spies were normally interrogated under 1. Thucydides, e.g., used kataskopoi for spies at 6.45.1 (they were not named but were distinguished from other sources reporting to the Syracusans) and 8.6.4 (the perioikos Phry- nis, discussed shortly); mounted scouts at 6.63.3; and of‹cial investigators at 4.27.3–4 (Cleon and Theagenes, chosen by the Athenians to investigate matters at Pylos) and 8.41.1 (men appointed to oversee the Spartan navarch Astyochus). The word kataskopos is not found in Homer—he instead used episkopos or skopos indiscriminately for spies, scouts, watchers, and overseers. -

WM210-220-230-240S/SI WM210-220-230-240S/SI Installation Instructions

INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS Instrucciones de instalación Istruzioni di installazione Installationsanleitung Installatie-instructies Instruções de Instalação Instructions d´installation WM-210SI WM-220SI WM-230SI WM-240SI Dual Stud Short Throw Wall Mounts Spanish Product Description German Product Description Portuguese Product Description Italian Product Description Dutch Product Description French Product Description WM210-220-230-240S/SI WM210-220-230-240S/SI Installation Instructions DISCLAIMER Milestone AV Technologies and its affiliated corporations and WARNING: Failure to read, thoroughly understand, and subsidiaries (collectively "Milestone"), intend to make this follow all instructions can result in serious personal injury, manual accurate and complete. However, Milestone makes no damage to equipment, or voiding of factory warranty! It is the claim that the information contained herein covers all details, installer’s responsibility to make sure all components are conditions or variations, nor does it provide for every possible properly assembled and installed using the instructions contingency in connection with the installation or use of this provided. product. The information contained in this document is subject to change without notice or obligation of any kind. Milestone makes no representation of warranty, expressed or implied, WARNING: Failure to provide adequate structural strength regarding the information contained herein. Milestone assumes for this component can result in serious personal injury or no responsibility for accuracy, completeness or sufficiency of damage to equipment! It is the installer’s responsibility to the information contained in this document. make sure the structure to which this component is attached can support five times the combined weight of all equipment. Chief® is a registered trademark of Milestone AV Technologies. -

Iver Nestos. According to Greek Mythology, the Foundation of the City

(Avdira). A city in Thrace (northern Greece); situated on Cape ra (a corruption of the medieval Polystylon), eleven miles northeast of iver Nestos.According to Greek mythology, the foundation of the city went to Heracles,whose eighth labor was the capture of the man-eatinghorses iomedes,king of the neighboringBistonians. However, the first attempt to Abdera, accordingto Herodotus,was made in the seventhcentury nc by ists from Clazomenae(Klazumen) in Ionia led by Tynisias,but they were n backby the Thracians.In 545nc the peopleof anotherIonian city, Teos rk), frnding Persiandomination intolerable,placed settlers on the site (in- ing the poet Anacreon)and reconstructedthe town. It controlled an exten- 2pgs-6s6veredwith vineyards and fertile,' accordingto Pindar. An ear of in is shownon its fine coins.However, the Abderanswere constantly at pains protect their territory from Thracian incursions.Nevertheless, their city was a centerfor trading with the Thracian (Odrysian)rulers of the hinterland, d provided a harbor for the commerce of upper Thrace in general. \\'hen the Persians came to Thrace in 5131512they took control of Abdera, did so once againtn 492.In 480 it was one of the halting placesselected Xerxesas he marchedthe Persianarmy along the northern shoresof the Ae- n toward Greece. As a member of the first Athenian Alliance (Delian ue) establishedafter the end of the PersianWars, it contributed (from 454 a sum of betweenten and fifteen talents,indicating its position as the third- hestcity in the League.ln 431,at the beginningof the PeloponnesianWar inst Sparta, tltook the lead in an endeavor to enroll Thrace (under the Odry- ruler Sitalces)and Macedoniain the Athenian cause.Although'Abderite' becamea synonym for stupidity, Abdera producedtwo fifth-century think- of outstandingdistinction, Democritusand Protagoras. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan LINDA JANE PIPER 1967

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 66-15,122 PIPER, Linda Jane, 1935- A HISTORY OF SPARTA: 323-146 B.C. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1966 History, ancient University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan LINDA JANE PIPER 1967 All Rights Reserved A HISTORY OF SPARTA: 323-1^6 B.C. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Linda Jane Piper, A.B., M.A. The Ohio State University 1966 Approved by Adviser Department of History PREFACE The history of Sparta from the death of Alexander in 323 B.C; to the destruction of Corinth in 1^6 B.C. is the history of social revolution and Sparta's second rise to military promi nence in the Peloponnesus; the history of kings and tyrants; the history of Sparta's struggle to remain autonomous in a period of amalgamation. It is also a period in Sparta's history too often neglected by historians both past and present. There is no monograph directly concerned with Hellenistic Sparta. For the most part, this period is briefly and only inci dentally covered in works dealing either with the whole history of ancient Sparta, or simply as a part of Hellenic or Hellenistic 1 2 history in toto. Both Pierre Roussel and Eug&ne Cavaignac, in their respective surveys of Spartan history, have written clear and concise chapters on the Hellenistic period. Because of the scope of their subject, however, they were forced to limit them selves to only the most important events and people of this time, and great gaps are left in between. -

ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences 5-2011 ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72 Emerson T. Brooking University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Comparative Politics Commons, Military History Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Brooking, Emerson T., "ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72" 01 May 2011. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/145. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/145 For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72 Abstract This study evaluates the military history and practice of the Roman Empire in the context of contemporary counterinsurgency theory. It purports that the majority of Rome’s security challenges fulfill the criteria of insurgency, and that Rome’s responses demonstrate counterinsurgency proficiency. These assertions are proven by means of an extensive investigation of the grand strategic, military, and cultural aspects of the Roman state. Fourteen instances of likely insurgency are identified and examined, permitting the application of broad theoretical precepts