9Th Dr. Ambedkar Memorial Lecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mining Activity As a Self-Invited Disaster of Man in the Upheaval

http://www.epitomejournals.com, Vol. 2, Issue 11, November 2016, ISSN: 2395-6968 MINING ACTIVITY AS A SELF-INVITED DISASTER OF MAN IN THE UPHEAVAL Akshay A. Yardi Guest Faculty, Dept. of English, Karnatak Arts College P. G. Centre, Dharwad, Karnataka State Mail: [email protected] Abstract The present paper focuses on the hazardous impacts of the mining on the rural community of Goa. The author Pundalik Naik has tried to show the real situation in the interior parts of Goa during the mid twentieth century. While the nature was getting destroyed because of the mine business, the mentality of the people also goes on changing. Heavy work at the mines becomes the profession of most of the villagers of a village by the name Kolamba and as the story moves on, we see how it takes toll on their happiness, prosperity and cordiality. The Upheaval tries to show the mining activity as not something natural but a self-invited disaster for man and the whole community of that village. This paper takes some incidents from the novel and analyses how the mining activity takes on the nerves of so many characters in the novel, prominent among them being Pandhari, Rukmini, Namdev (Nanu) and Kesar. The story of one family is just a miniature to represent the story of the whole village and rural community of Goa. Taking into consideration several incidents from the novel, the paper comes to a conclusion that it is man‟s self-invited disaster. Keywords: Mining, Disaster, Culture, Disintegration, Community, Degradation, Addiction 101 AAY Dr. -

O Sai ! Thou Art Our Vithu Mauli ! O Sai ! Thy Shirdi Is Our Pandharpur !

O Sai ! Thou art our Vithu Mauli ! O Sai ! Thy Shirdi is our Pandharpur ! Shirdi majhe Pandharpur l Sai Baba Ramavar ll 1 ll Shuddha Bhakti Chandrabhaga l Bhav Pundalik jaga ll 2 ll Ya ho ya ho avghejan l Kara Babansi vandan ll 3 ll Ganu mhane Baba Sai l Dhav paav majhe Aai ll In this Abhang, which is often recited as a Prarthana (prayer), Dasganu Maharaj describes that Shirdi is his Pandharpur where his God resides. He calls upon the devotees to come and take shelter in the loving arms of Sai Baba. Situated in the devout destination of Pandharpur is a temple that is believed to be very old and has the most surprising aspects that only the pilgrim would love to feel and understand. This is the place where the devotees throng to have a glimpse of their favourite Lord. The Lord here is seen along with His consort Rukmini (Rama). The impressive Deities in their black colour look very resplendent and wonderful. Situated on the banks of the river Chandrabhaga or Bhima, this place is also known as Pandhari, Pandurangpur, Pundalik kshetra. The Skandha and the Padma puranas refer to places known as Pandurang kshetra and Pundalik kshetra. The Padma puran also mentions Dindiravan, Lohadand kshetra, Lakshmi tirtha, and Mallikarjun van, names that are associated with Pandharpur. The presiding Deity has many different names like Pandharinath, Pandurang, Pandhariraya, Vithai, Vithoba, Vithu Mauli, Vitthal Gururao etc. But, the well-known and commonly used names are Pandurang or Vitthal or Vithoba. The word Vitthal is said to be derived from the Kannad (a language spoken in the southern parts of India) word for Lord Vishnu. -

Namdev Life and Philosophy Namdev Life and Philosophy

NAMDEV LIFE AND PHILOSOPHY NAMDEV LIFE AND PHILOSOPHY PRABHAKAR MACHWE PUBLICATION BUREAU PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala 1990 Second Edition : 1100 Price : 45/- Published by sardar Tirath Singh, LL.M., Registrar Punjabi University, Patiala and printed at the Secular Printers, Namdar Khan Road, Patiala ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to the Punjabi University, Patiala which prompted me to summarize in tbis monograpb my readings of Namdev'\i works in original Marathi and books about him in Marathi. Hindi, Panjabi, Gujarati and English. I am also grateful to Sri Y. M. Muley, Director of the National Library, Calcutta who permitted me to use many rare books and editions of Namdev's works. I bave also used the unpubIi~bed thesis in Marathi on Namdev by Dr B. M. Mundi. I bave relied for my 0pIDlOns on the writings of great thinkers and historians of literature like tbe late Dr R. D. Ranade, Bhave, Ajgaonkar and the first biographer of Namdev, Muley. Books in Hindi by Rabul Sankritya)'an, Dr Barathwal, Dr Hazariprasad Dwivedi, Dr Rangeya Ragbav and Dr Rajnarain Maurya have been my guides in matters of Nath Panth and the language of the poets of this age. I have attempted literal translations of more than seventy padas of Namdev. A detailed bibliography is also given at the end. I am very much ol::lig(d to Sri l'and Kumar Shukla wbo typed tbe manuscript. Let me add at the end tbat my family-god is Vitthal of Pandbarpur, and wbat I learnt most about His worship was from my mother, who left me fifteen years ago. -

Glories of Srimad Bhagavatam Hare Krishna Prabhujis and Matajis

Glories of Srimad Bhagavatam Date: 2007-04-08 Author: Sudarshana devi dasi Hare Krishna Prabhujis and Matajis, Please accept my humble obeisances. All glories to Srila Prabhupada and Srila Gurudev. In the 1st chapter of Seventh Canto in Srimad Bhagavatam, Parikshit Maharaj inquires Srila Sukadeva Goswami to explain him about the impartial nature of Supreme Lord. Before beginning any service, one must offer their obeisances to their spiritual master and in the following verse, Sukadeva Goswami offers his respects to his spiritual master Srila Vyasadev through verses 7.1.4-5, before explaining the glories of Lord to Maharaj Parikshit. śrī-ṛṣir uvāca sādhu pṛṣṭaṁ mahārāja hareś caritam adbhutam yad bhāgavata-māhātmyaṁ bhagavad-bhakti-vardhanam gīyate paramaṁ puṇyam ṛṣibhir nāradādibhiḥ natvā kṛṣṇāya munaye kathayiṣye hareḥ kathām The great sage Sukadeva Goswami said: My dear King, you have put before me an excellent question. Discourses concerning the activities of the Lord, in which the glories of His devotees are also found, are extremely pleasing to devotees. Such wonderful topics always counteract the miseries of the materialistic way of life. Therefore great sages like Narada always speak upon Srimad-Bhaagavatam because it gives one the facility to hear and chant about the wonderful activities of the Lord. Let me offer my respectful obeisances unto Srila Vyasadeva and then begin describing topics concerning the activities of Lord Hari. In the above verse, Sukadev Goswami has very nicely highlighted. a) Discourses about Lord and His devotees are pleasing to all b) Such topics counteract the miseries of materialistic way of life c) Need for speaking Srimad Bhagavatam "Always" Few days back, I was listening to one of the lectures of my spiritual master, HH Mahavishnu Goswami Maharaj wherein Maharaj was telling about the increase in number of psychiatric patients in this age. -

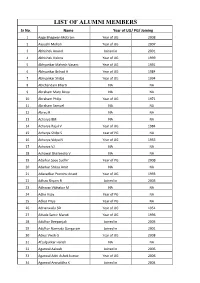

LIST of ALUMNI MEMBERS Sr No

LIST OF ALUMNI MEMBERS Sr No. Name Year of UG/ PG/ Joining 1 Aage Bhagwan Motiram Year of UG 2008 2 Aayushi Mohan Year of UG 2007 3 Abhishek Anand Joined in 2001 4 Abhishek Vishnu Year of UG 1999 5 Abhyankar Mahesh Vasant Year of UG 1991 6 Abhyankar Brihad A Year of UG 1984 7 Abhyankar Shilpa Year of UG 1994 8 Abichandani Bharti NA NA 9 Abraham Mary Binsu NA NA 10 Abraham Philip Year of UG 1971 11 Abraham Samuel NA NA 12 Abreu R NA NA 13 Acharya BM NA NA 14 Acharya Rajul V Year of UG 1984 15 Acharya Shilpi S Year of PG NA 16 Acharya Vidya N Year of UG 1955 17 Acharya VJ NA NA 18 Achawal Shailendra V NA NA 19 Adarkar Saee Sudhir Year of PG 2008 20 Adarkar Shilpa Amit NA NA 21 Adavadkar Pranshu Anant Year of UG 1993 22 Adhau Shyam R Joined in 2003 23 Adhavar Vibhakar M NA NA 24 Adhe Vijay Year of PG NA 25 Adkar Priya Year of PG NA 26 Adrianwalla SD Year of UG 1951 27 Adsule Samir Maruti Year of UG 1996 28 Adulkar Deepanjali Joined in 2005 29 Adulkar Namrata Gangaram Joined in 2001 30 Adwe Vivek G Year of UG 2008 31 Afzulpurkar Harish NA NA 32 Agarwal Aakash Joined in 2005 33 Agarwal Aditi Ashok kumar Year of UG 2006 34 Agarwal Aniruddha K Joined in 2004 35 Agarwal AVedprakash NA NA 36 Agarwal Bharat R NA NA 37 Agarwal CS NA NA 38 Agarwal Gayatri NA NA 39 Agarwal Hemant Shyam NA NA 40 Agarwal KK NA NA 41 Agarwal Krishnakumar NA NA 42 Agarwal Manit Sanjay Year of UG 2008 43 Agarwal Mohan B Year of UG 1970 44 Agarwal Nisha Rahul Year of PG MD PSM 09 45 Agarwal Parmanand Year of PG 2012 46 Agarwal Prakashchand G Year of UG 1998 47 Agarwal Rahul -

SHRISAILEELA - JULY-AUGUEST-2005 English Section

SHRISAILEELA - JULY-AUGUEST-2005 English Section “Vithu-mauli, Sai-mauli” : Mrs. Mugdha Diwadkar Shree Dattatreya Sahasra Nama : Prof. Dr. K. J. Ajabia Shri Pant Maharaj as a Teacher : Naresh Dharwadkar In Sai’s Proximity : Mrs. Mugdha Diwadkar Is Baba Living & Helping now : Jyoti Ranjan SHREE SAI BABA SANSTHAN TRUST (SHIRDI) Management Committee Shri Jayant Murlidhar Sasane Shri Shankararao Genuji Kolhe Shri Bhausaheb Rajaram Wakchaure Chairman Vice-chairman Executive Officer This site is developed and maintained by Shri Saibaba Sansthan Trust. © Shri Saibaba Sansthan Trust, Shirdi. Homepage SHRISAILEELA - JULY-AUGUST-2005 Vithu-mauli, Sai-mauli Shree Dattatreya Sahasra Nama Shri Pant Maharaj as a Teacher In Sai’s Proximity Is Baba Living & Helping now “YOU ARE VITHU-MAULI*, YOU ARE SAI-MAULI !” — Mrs. Mugdha Diwadkar Preamble Pandurang of Pandharpur town is the Deity dear to many, not only from Maharashtra and Karnatak but also for several people from outside Maharashtra ! The heartfelt love of Vitthal pulls the devotees to Pandharpur - forgetting the differences in religions and castes. Due to this congregation, Pandharpur has become a regional cultural center. Many devotees fervently believe that Pandurang or Vitthal of Pandhari is Lord Shrikrishna. This Deity is a beautiful statue carved out of black stone. Actually, the complexion of Pandurang (Pandurang Kanti) is supposed to be fair and that’s why He is called ‘Pandu-rang’. However, at the time of Amrut Manthan, the poison ‘Halahal’ came out of the seven seas and Lord Shankar digested it. Therefore, Lord Shankar (and in turn Lord Vishnu) acquired a dark complexion. Similarly, Lord Vishnu took ‘Amrut’ and hence, Lord Shankar became fair like camphor (Karpoor Gaur). -

Rayat Shlkshan Sansthl'l • Index Sr

Rayat Shlkshan Sansthl'l • Index Sr. Subject Writer Page No. No -- 50 ~~~~WWiT "SIT . ~~~. 185 51 lfmftlT mtTun ~~ lJ!1t }{T. ~ tmw 'IfTT<lff 188 rrr. if. ~ rft.;ft. 52 ~l~1S qJ '3WI' q $II~it m m.!f.ftcfi~.~. 191 53 "~~6IfllT41 ~~ mftm ~ ~ : Jl1 . ~.~~~ 194 lW!T~~ " 54 ('l. <m) 91 ~ ffiIT ~ 197 ,. Iltil<I"<;:Iil11 ~fdi\ltlld)(1 'Il'i\ll: ;;mfrit ~" 55 ~'l,~~~'Q'1Dcl'OOqlffiWT~~~ m.!f.TTT<B qlJ.~. 201 • 56 ~~~:-~~ m.s'f.~ ~ 'R'l 203 57 ~-'QCIi~~ m.~.~ ;:1I'(11101~ICl ~ 207 58 ~~~:~~~ Jl1.~~~ 210 • 59 ~~~ ~ ~ 'ifOOCI'OO ~ m.~oft.~ 214 ~ - . .. 60 mcrm ~ : 'QCIi ~~61ff1 'Ii ~efq Jl1 . if.~~~ 221 61 tcrmfr ~m ~ 'iT Cl'ffifCT : ~ q[{Jgll~ifl ~eftT if.~~~ 223 62 Politics of Development and People's Agitation Prof. Mahajan Viraj Dattan'aya 226 . -- 63 ACultural Encounter Between East and West in the Colonial Rabi Ranjan Sen 233 Period: ACase ~tudy of Paramaha ~a Yogan ~ da and Kri~a Yoga . --- .. 64 ~ qRfl~llf\cl ~ 1857 T41 ~ m. tr.~.qycrn 240 ~ 65 'Il'mI1'ft~, ~ N-IT q ~ ~. -tt . ~. 00s 243 • ~~ari Samprad~y Dr Swarali Chandrakant Kulkarni, 247 67 W f~m ~ ~ fcrcr:rq, tir1llJ sT .iffb" fcriJCIT 1jfcrq 252 68 ~ . -m, ~ m<) 1l61~1'S:liZll ~ m. ~~ . tfI . 256 • qR'Hf'1llf\cl 1lffiR . 69 fiHhlCllI\.,f1'1 ~ ~I<!l'wllill ~ m.~ 3iorrGrn ~ 259 70 ~ ~~ 3l1ftlT \ifT1Tft1q; ~ AT.~ .31R.~.trcIR 262 71 ~1~'f.I'Olcfci\ lIT'iml.~ . ~ 266 72 q61(I~trftcllimT<f ~ crr'raft~ ~ ~ m. m?; 'ffil)q ~ 269 73 w~ ~Jiill-((lIi~ IJI • 3W . ~ . ~ JJYf 270 D.P. -

North American Konkani Newsletter Volume XXVIII No

K habbar North American Konkani Newsletter Volume XXVIII No. 3 July, August, September - 2005 From: The Honorary Editor, "Khabbar" P. O. Box 222 Lake Jackson, TX 77566 - 0222 XXVIII-3 ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED FIRST CLASS TO: Khabbar XXVIII No. 3 Page: 1 Khabbar Follies In this section, Khabbar looks into the Konkani community and anything and everything that is Konkani from a Konkani point of view. The names will never be published but geographic location will be identified in general terms. There is no doubt in my mind that Khabbar is a part & parcel “We received the Khabbar without the text -- only the cover. of life of Konkanis in North America. In fact, Khabbar has Would appreciate your sending the newsletter again. developed a special relation with most of the Konkani families I was amused to read about the person whose wife took and here are some examples of those close encounters of a Khabbar with her when she went to India. I do take this different kind….…… newsletter whenever I travel too. -- We don’t leave home --------------------------------------------------------------------------- without Khabbar!!” -- Editor’s Reply: I never realized how much our community is attached to Watch out American Express! Khabbar till I got this note from this family in NY after they ***** received their Khabbar in March of this year: I suspect quite a few families read Khabbar from the front to the back without missing a line but I never thought that they “Dear Vasanthmaam, scan the whole issue with a magnifying glass to note each and Thank you for all your “Hoon Khabbar”. -

List of Names Drawing Central Samman Pension Sl No

List of Names drawing Central Samman Pension Sl no. Name State ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 1 MRS. JAMUNA KUMARI ISLANDS 2 BOLLAM NAGALAXMI ANDHRA PRADESH 3 KOMPALLY RADHMMA W/O LATE BAANDHRA PRADESH 4 A HANUMANTHA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 5 KALYANAPU ANASURYAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 6 RAMISETTI VENKATA MAHA LAXMI ANDHRA PRADESH 7 LAGADAPATI CHENCHAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 8 DAMULURI VENKATESWARLU ANDHRA PRADESH 9 N SUBHADRAMMA W/O LATE KOTEANDHRA PRADESH 10 LAGADAPATI KAMALAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 11 LAGADAPATI NARASIMHA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 12 LAGADAPATI PAKEERAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 13 VUNNAM VENKATESWARLU ANDHRA PRADESH 14 VUTUKURU YASODASMMA W/O LATANDHRA PRADESH 15 J BUTCHAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 16 AKKINENI NIRMALA ANDHRA PRADESH 17 LAGADAPATI NAGESWARA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 18 YERNENI VENKATA RAVAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 19 K DHNALAXMI W/O LATE BASAVAIAANDHRA PRADESH 20 RAMISETTI PEDDA VENKATESWARLANDHRA PRADESH 21 KOPPU GOVINDAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 22 GADDE SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 23 NIRUKONDA KOTESWARA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 24 KOLLI BHARATHA VENKATA ANDHRA PRADESH 25 GADDE RAGHAVAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 26 KOTA VENKATA RAVAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 27 CHIRUMAMILLA SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 28 CHERUKURI KAMALAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 29 S SUSEELAMMA DEVI W/O LATE SU ANDHRA PRADESH 30 SURYADEVARA V KR MURTHY ANDHRA PRADESH 31 DANTALA SEETHAMMA W/O LATE DANDHRA PRADESH 32 CHAVALA NAGAMMA W/O LATE HAVANDHRA PRADESH 33 SURYADEVARA CHANDRASEKHARAANDHRA PRADESH 34 BAHUDODDA KONDAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 35 BANDI SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 36 ANUMALA ASWADHA NARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 37 KESARI PERAMMA ANDHRA -

Summer Showers in Brindavan 1972

SUMMER SHOWERS IN BRINDAVAN 1972 Discourses by BHAGAVAN SRI SATHYA SAI BABA Delivered during the summer course held for college students at Whitefield, Bangalore, India Page i © Sri Sathya Sai Books and Publications Trust Prashanthi Nilayam, India The copyright and the rights of translation in any language are re- served by the Publishers. No part, para, passage, text or photograph or art work of this book should be reproduced, transmitted or util- ized, in original language or by translation, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or by any information, storage and retrieval system, except with prior permis- sion, in writing from Sri Sathya Sai Books & Publications Trust, Prashanthi Nilayam (Andhra Pradesh) India, except for brief pas- sages quoted in book review. This book can be exported from India only by the Publishers Sri Sathya Sai Books and Publications Trust, Prashanthi Nilayam (India). Printing rights granted by arrangement with the Sri Sathya Sai Books and Publications Trust, Prashanthi Nilayam, India, To: Sathya Sai Baba Society and Sathya Sai Book Center of America 305 West First Street Tustin, CA 92780-3108 USA ISBN 1-57836-050-1 Revised edition, Copyright © 1998 Sathya Sai Book Center of America Page ii Contents Message from Bhagavan Sri Sathya Sai Baba iv Preface ix 1. Exhortation to Students 1 2. Vedic Truths Belong to the Whole World 8 3. Nature of the Human Mind 21 4. What the Upanishads Teach Us 33 5. The Nature of Truth 46 6. ‘Kama’ and ‘Krodha’ 57 7. ‘Purusha’ and ‘Prakruthi’ 68 8. Lessons from the Bhagavad Gita 77 9. -

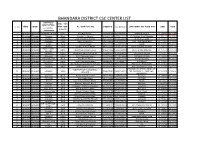

Bhandara District Csc Center List

BHANDARA DISTRICT CSC CENTER LIST ग्रामपंचायत/ झोन / वा셍ड महानगरपाललका Sr. No. जि쥍हा तालुका (फ啍त शहरी कᴂद्र चालक यांचे नाव मोबाईल क्र. CSC-ID/MOL- आपले सरकार सेवा कᴂद्राचा प配ता अ啍ांश रेखांश /नगरपररषद कᴂद्रासाठी) /नगरपंचायत 1 Bhandara Bhandara SHASTRI CHOUK Urban Amit Raju Shahare 9860965355 753215550018 SHASTRI CHOUK 21.177876 79.66254 2 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Avinash D. Admane 8208833108 317634110014 Dr. Mukharji Ward,Bhandara 21.1750113 79.65582 3 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Jyoti Wamanrao Makode 9371134345 762150550019 NEAR UCO BANK 21.174854 79.64352 4 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Sanjiv Gulab Bhure 9595324694 633079050019 CIVIL LINE BHANDARA 21.171533 79.65356 5 Bhandara Bhandara paladi Rural Gulshan Gupta 9423414199 622140700017 paladi 21.169466 79.66144 6 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban SUJEET N MATURKAR 9970770298 712332740018 RAJIV GANDHI SQUARE 21.1694655 79.66144 RAJIV GANDI 7 Bhandara Bhandara Urban Basant Shivshankar Bisen 9325277936 637272780014 RAJIV GANDI SQUARE 21.167537 79.65599 SQUARE 8 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Mohd Wasi Mohd Rafi Sheikh 8830643611 162419790010 RAJENDRA NAGAR 21.16685 79.655364) 9 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Kartik Gyaniwant Akare 9326974400 311156120014 IN FRONT OF NH6 21.166096 79.66028 10 Bhandara Bhandara Tekepar[kormbi] Rural Anita Eknath Bhure 9923719175 217736610016 Tekepar[kormbi] 21.1642922 79.65682 11 Bhandara Bhandara BHANDARA Urban Priya Pritamlal Kumbhare 9049025237 114534420013 BHANDARA 21.162895 79.64346 12 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Md. Sarfaraz Nawaz Md Shrif Sheikh 8484860484 365824810010 POHA GALI,BHANDARA 21.162768 79.65609 13 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Nitesh Natthuji Parate 9579539546 150353710012 Near Bhandara Bus Stop 21.161485 79.65576 FRIENDLY INTERNET ZONE, Z.P TARKESHWAR WASANTRAO 14 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban 9822359897 434443140013 SQ. -

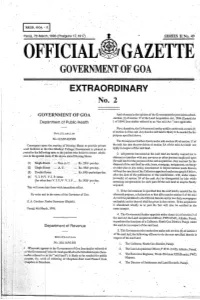

Official. Gazette

I·REGD. oo~ -sl Panaji, 7th March,1996 (Phalguna 17,1917) I. • SERIES II No. 49 .OFFICIAL. GAZETTE • GOVERNMENT' OF GOA EXTRAORDINARY No.2 : GQVERNMENT OF GOA Arid whereas in the opinion.of the Govenunent the provisions ohub -section (I) of section 17 of the Land Acquisition Act, 1894(CentrillAct I of 1894) (hereinafter to as "the said Act") are applicable .. Department of Public He,:J.ith refetT~d , Now. therefore. the Govcriuncnthereby notifies under sub-section (1) Notification of section 4 of the said Act. that the said land isl~ely to be needed for the purpo~e specified abov~. No.ll/3/95-IIIPHD The Govenunent further directs under sub-section (4) of section 17 of Consequent upon the, starting ofNuising Home to' provide 'private the said Act that the provisions of section 5A.of the said Act shall not ward facilities at the-Gaa-Medical College.',Gavernment is pleased to apply in respect of the said hind." - prescribe theJ6110wing rates,to the patie~t who desire to seCQ.re adfJ1is 2. All persons interested. in the said land are hereby warned not to sian in the~eci~ r_~m_~f.the a~~e stated Nursing Home. obstruct or interfere with any surveyor. or other persons empioyed upon ~le said land for the purpose of the said aCquisition,. Any contract for the (I) SingleRoon'l ; .. NonA, c. Rs. 2501- per day. disposal of the said land by sale. lease, mortgage,' assigrunent, exchange (2) Smgle Room .;. A. C,' ... Rs, 350f-·per day. or otherwise qr any outlay commenced o"r improvements made thereon (3) Double Room .