Bhakti As Protest1 Rohini Mokashi-Punekar, Indian Institute of Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sant Dnyaneshwar - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Sant Dnyaneshwar - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Sant Dnyaneshwar(1275 – 1296) Sant Dnyaneshwar (or Sant Jñaneshwar) (Marathi: ??? ??????????) is also known as Jñanadeva (Marathi: ????????). He was a 13th century Maharashtrian Hindu saint (Sant - a title by which he is often referred), poet, philosopher and yogi of the Nath tradition whose works Bhavartha Deepika (a commentary on Bhagavad Gita, popularly known as "Dnyaneshwari"), and Amrutanubhav are considered to be milestones in Marathi literature. <b>Traditional History</b> According to Nath tradition Sant Dnyaneshwar was the second of the four children of Vitthal Govind Kulkarni and Rukmini, a pious couple from Apegaon near Paithan on the banks of the river Godavari. Vitthal had studied Vedas and set out on pilgrimages at a young age. In Alandi, about 30 km from Pune, Sidhopant, a local Yajurveda brahmin, was very much impressed with him and Vitthal married his daughter Rukmini. After some time, getting permission from Rukmini, Vitthal went to Kashi(Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh, India), where he met Ramananda Swami and requested to be initiated into sannyas, lying about his marriage. But Ramananda Swami later went to Alandi and, convinced that his student Vitthal was the husband of Rukmini, he returned to Kashi and ordered Vitthal to return home to his family. The couple was excommunicated from the brahmin caste as Vitthal had broken with sannyas, the last of the four ashrams. Four children were born to them; Nivrutti in 1273, Dnyandev (Dnyaneshwar) in 1275, Sopan in 1277 and daughter Mukta in 1279. According to some scholars their birth years are 1268, 1271, 1274, 1277 respectively. -

Three Women Sants of Maharashtra: Muktabai, Janabai, Bahinabai

Three Women Sants of Maharashtra Muktabai, Janabai, Bahinabai by Ruth Vanita Page from a handwritten manuscript of Sant Bahina’s poems at Sheor f”kÅj ;sFkhy gLrfyf[kukP;k ,dk i~’Bkpk QksVks NUMBER 50-51-52 (January-June 1989) An ant flew to the sky and swallowed the sun Another wonder - a barren woman had a son. A scorpion went to the underworld, set its foot on the Shesh Nag’s head. A fly gave birth to a kite. Looking on, Muktabai laughed. -Muktabai- 46 MANUSHI THE main trends in bhakti in Maharashtra is the Varkari tradition which brick towards Krishna for him to stand on. Maharashtra took the form of a number of still has the largest mass following. Krishna stood on the brick and was so sant traditions which developed between Founded in the late thirteenth and early lost in Pundalik’s devotion that he forgot the thirteenth and the seventeenth fourteenth centuries1 by Namdev (a sant to return to heaven. His wife Rukmani had centuries. The sants in Maharashtra were of the tailor community, and Jnaneshwar, to come and join him in Pandharpur where men and women from different castes and son of a socially outcasted Brahman) who she stands as Rakhumai beside Krishna in communities, including Brahmans, wrote the famous Jnaneshwari, a versified the form of Vitthal (said to be derived from Vaishyas, Shudras and Muslims, who commentary in Marathi on the Bhagwad vitha or brick). emphasised devotion to god’s name, to Gita, the Varkari (pilgrim) tradition, like the The Maharashtrian sants’ relationship the guru, and to satsang, the company of Mahanubhav, practises nonviolence and to Vitthal is one of tender and intimate love. -

Review of Research Impact Factor : 5.2331(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.2331(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 7 | issUe - 7 | apRil - 2018 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ KAGAD OR PAPER MENTIONS BY MEDIEVAL SAINTS Prof. Dikonda Govardhan Krushnahari Assistant Professor,Department of History , Arts & Commerce College, Madha. ABSTRACT: Maharashtra is known as the land of Saints. The period which the great saints live in is known as Saint’s period- Warkari Period. From Sant Dnyaneshwar to Sant Ramdas every saint has glorified and described humanity. Their poem is called ‘Abhangas’. These Abhangas has the greatest important in Marathi culture and literature. KEYWORDS : Sant Dnyaneshwar , Marathi culture and literature. INTRODUCTION The purpose behind mentioning the point here is ample examples and references are available which mention the glorification or description paper made by several saints. Thus it is needless to say that the social, political and cultural fields were greatly influence by the paper. Some of the stanzas of Abhangas of some saints like Sant Dnyaneshwar, Sant Namdev, Sant Tukaram; Sant Ramdasetc. are being shared here. Just in order to be acquainted with the mentioning’s of paper in various old writings. The mentioning of paper as the tool of writing is found in Dynaneshwari(Rajwade Prat or Copy)– He bahu aso panditoo | Dharunu balakacha hatu | voli lehe vegavantu | Apanachi. || Adhyay 13, ovi – 307 || Sukhachi lipi pusali || Adhyay 3, ovi – 246 || Doghanchi lihili phadi || Adhyay 4, ovi 52 || Aakhare Pusileya na puse arth jaisa || Adhyay 8, ovi 104 ||1 If the above lines of Dynaneshwari considered, it makes clear that paper was in the daily use as the writing tool even in the way back ago, ancient period. -

Mining Activity As a Self-Invited Disaster of Man in the Upheaval

http://www.epitomejournals.com, Vol. 2, Issue 11, November 2016, ISSN: 2395-6968 MINING ACTIVITY AS A SELF-INVITED DISASTER OF MAN IN THE UPHEAVAL Akshay A. Yardi Guest Faculty, Dept. of English, Karnatak Arts College P. G. Centre, Dharwad, Karnataka State Mail: [email protected] Abstract The present paper focuses on the hazardous impacts of the mining on the rural community of Goa. The author Pundalik Naik has tried to show the real situation in the interior parts of Goa during the mid twentieth century. While the nature was getting destroyed because of the mine business, the mentality of the people also goes on changing. Heavy work at the mines becomes the profession of most of the villagers of a village by the name Kolamba and as the story moves on, we see how it takes toll on their happiness, prosperity and cordiality. The Upheaval tries to show the mining activity as not something natural but a self-invited disaster for man and the whole community of that village. This paper takes some incidents from the novel and analyses how the mining activity takes on the nerves of so many characters in the novel, prominent among them being Pandhari, Rukmini, Namdev (Nanu) and Kesar. The story of one family is just a miniature to represent the story of the whole village and rural community of Goa. Taking into consideration several incidents from the novel, the paper comes to a conclusion that it is man‟s self-invited disaster. Keywords: Mining, Disaster, Culture, Disintegration, Community, Degradation, Addiction 101 AAY Dr. -

O Sai ! Thou Art Our Vithu Mauli ! O Sai ! Thy Shirdi Is Our Pandharpur !

O Sai ! Thou art our Vithu Mauli ! O Sai ! Thy Shirdi is our Pandharpur ! Shirdi majhe Pandharpur l Sai Baba Ramavar ll 1 ll Shuddha Bhakti Chandrabhaga l Bhav Pundalik jaga ll 2 ll Ya ho ya ho avghejan l Kara Babansi vandan ll 3 ll Ganu mhane Baba Sai l Dhav paav majhe Aai ll In this Abhang, which is often recited as a Prarthana (prayer), Dasganu Maharaj describes that Shirdi is his Pandharpur where his God resides. He calls upon the devotees to come and take shelter in the loving arms of Sai Baba. Situated in the devout destination of Pandharpur is a temple that is believed to be very old and has the most surprising aspects that only the pilgrim would love to feel and understand. This is the place where the devotees throng to have a glimpse of their favourite Lord. The Lord here is seen along with His consort Rukmini (Rama). The impressive Deities in their black colour look very resplendent and wonderful. Situated on the banks of the river Chandrabhaga or Bhima, this place is also known as Pandhari, Pandurangpur, Pundalik kshetra. The Skandha and the Padma puranas refer to places known as Pandurang kshetra and Pundalik kshetra. The Padma puran also mentions Dindiravan, Lohadand kshetra, Lakshmi tirtha, and Mallikarjun van, names that are associated with Pandharpur. The presiding Deity has many different names like Pandharinath, Pandurang, Pandhariraya, Vithai, Vithoba, Vithu Mauli, Vitthal Gururao etc. But, the well-known and commonly used names are Pandurang or Vitthal or Vithoba. The word Vitthal is said to be derived from the Kannad (a language spoken in the southern parts of India) word for Lord Vishnu. -

Namdev Life and Philosophy Namdev Life and Philosophy

NAMDEV LIFE AND PHILOSOPHY NAMDEV LIFE AND PHILOSOPHY PRABHAKAR MACHWE PUBLICATION BUREAU PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala 1990 Second Edition : 1100 Price : 45/- Published by sardar Tirath Singh, LL.M., Registrar Punjabi University, Patiala and printed at the Secular Printers, Namdar Khan Road, Patiala ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to the Punjabi University, Patiala which prompted me to summarize in tbis monograpb my readings of Namdev'\i works in original Marathi and books about him in Marathi. Hindi, Panjabi, Gujarati and English. I am also grateful to Sri Y. M. Muley, Director of the National Library, Calcutta who permitted me to use many rare books and editions of Namdev's works. I bave also used the unpubIi~bed thesis in Marathi on Namdev by Dr B. M. Mundi. I bave relied for my 0pIDlOns on the writings of great thinkers and historians of literature like tbe late Dr R. D. Ranade, Bhave, Ajgaonkar and the first biographer of Namdev, Muley. Books in Hindi by Rabul Sankritya)'an, Dr Barathwal, Dr Hazariprasad Dwivedi, Dr Rangeya Ragbav and Dr Rajnarain Maurya have been my guides in matters of Nath Panth and the language of the poets of this age. I have attempted literal translations of more than seventy padas of Namdev. A detailed bibliography is also given at the end. I am very much ol::lig(d to Sri l'and Kumar Shukla wbo typed tbe manuscript. Let me add at the end tbat my family-god is Vitthal of Pandbarpur, and wbat I learnt most about His worship was from my mother, who left me fifteen years ago. -

Glories of Srimad Bhagavatam Hare Krishna Prabhujis and Matajis

Glories of Srimad Bhagavatam Date: 2007-04-08 Author: Sudarshana devi dasi Hare Krishna Prabhujis and Matajis, Please accept my humble obeisances. All glories to Srila Prabhupada and Srila Gurudev. In the 1st chapter of Seventh Canto in Srimad Bhagavatam, Parikshit Maharaj inquires Srila Sukadeva Goswami to explain him about the impartial nature of Supreme Lord. Before beginning any service, one must offer their obeisances to their spiritual master and in the following verse, Sukadeva Goswami offers his respects to his spiritual master Srila Vyasadev through verses 7.1.4-5, before explaining the glories of Lord to Maharaj Parikshit. śrī-ṛṣir uvāca sādhu pṛṣṭaṁ mahārāja hareś caritam adbhutam yad bhāgavata-māhātmyaṁ bhagavad-bhakti-vardhanam gīyate paramaṁ puṇyam ṛṣibhir nāradādibhiḥ natvā kṛṣṇāya munaye kathayiṣye hareḥ kathām The great sage Sukadeva Goswami said: My dear King, you have put before me an excellent question. Discourses concerning the activities of the Lord, in which the glories of His devotees are also found, are extremely pleasing to devotees. Such wonderful topics always counteract the miseries of the materialistic way of life. Therefore great sages like Narada always speak upon Srimad-Bhaagavatam because it gives one the facility to hear and chant about the wonderful activities of the Lord. Let me offer my respectful obeisances unto Srila Vyasadeva and then begin describing topics concerning the activities of Lord Hari. In the above verse, Sukadev Goswami has very nicely highlighted. a) Discourses about Lord and His devotees are pleasing to all b) Such topics counteract the miseries of materialistic way of life c) Need for speaking Srimad Bhagavatam "Always" Few days back, I was listening to one of the lectures of my spiritual master, HH Mahavishnu Goswami Maharaj wherein Maharaj was telling about the increase in number of psychiatric patients in this age. -

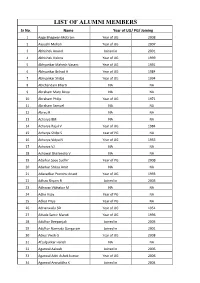

LIST of ALUMNI MEMBERS Sr No

LIST OF ALUMNI MEMBERS Sr No. Name Year of UG/ PG/ Joining 1 Aage Bhagwan Motiram Year of UG 2008 2 Aayushi Mohan Year of UG 2007 3 Abhishek Anand Joined in 2001 4 Abhishek Vishnu Year of UG 1999 5 Abhyankar Mahesh Vasant Year of UG 1991 6 Abhyankar Brihad A Year of UG 1984 7 Abhyankar Shilpa Year of UG 1994 8 Abichandani Bharti NA NA 9 Abraham Mary Binsu NA NA 10 Abraham Philip Year of UG 1971 11 Abraham Samuel NA NA 12 Abreu R NA NA 13 Acharya BM NA NA 14 Acharya Rajul V Year of UG 1984 15 Acharya Shilpi S Year of PG NA 16 Acharya Vidya N Year of UG 1955 17 Acharya VJ NA NA 18 Achawal Shailendra V NA NA 19 Adarkar Saee Sudhir Year of PG 2008 20 Adarkar Shilpa Amit NA NA 21 Adavadkar Pranshu Anant Year of UG 1993 22 Adhau Shyam R Joined in 2003 23 Adhavar Vibhakar M NA NA 24 Adhe Vijay Year of PG NA 25 Adkar Priya Year of PG NA 26 Adrianwalla SD Year of UG 1951 27 Adsule Samir Maruti Year of UG 1996 28 Adulkar Deepanjali Joined in 2005 29 Adulkar Namrata Gangaram Joined in 2001 30 Adwe Vivek G Year of UG 2008 31 Afzulpurkar Harish NA NA 32 Agarwal Aakash Joined in 2005 33 Agarwal Aditi Ashok kumar Year of UG 2006 34 Agarwal Aniruddha K Joined in 2004 35 Agarwal AVedprakash NA NA 36 Agarwal Bharat R NA NA 37 Agarwal CS NA NA 38 Agarwal Gayatri NA NA 39 Agarwal Hemant Shyam NA NA 40 Agarwal KK NA NA 41 Agarwal Krishnakumar NA NA 42 Agarwal Manit Sanjay Year of UG 2008 43 Agarwal Mohan B Year of UG 1970 44 Agarwal Nisha Rahul Year of PG MD PSM 09 45 Agarwal Parmanand Year of PG 2012 46 Agarwal Prakashchand G Year of UG 1998 47 Agarwal Rahul -

Chokhamela and Eknath

Chokhamela and Eknath: Two Bhakti Modes of Legitimacy for Modern Change ELEANOR ZELLIOT Carleton College, Northfield, U.S.A. C HOKHAMELA, a thirteenth to fourteenth century Maharashtrian santl in the bhakti tradition, and Eknath, a sixteenth century sant, are both revered figures in the Warkari sampradaya, 2 the tradition of pilgrimage to Pan- dharpur which marks the important bhakti movement in the Marathi-speaking area. The lives of both are known by legend; their songs are sung by devotees on the pilgrimage and in bhajan sessions. Chokhamela was a Mahar, the only important bhakti figure in Maharashtra from an Untouchable caste. Eknath was a Brahman from the holy city of Paithan who wrote about Chokhamela, ate with Mahars, allowed Untouchables into his bhajans, and wrote poems in the persona of a Mahar who was wiser in spiritual matters than the Brahmans. Both, then, offer models for contemporary change in regard to Un- touchability : even though an Untouchable, Chokhamela achieved sanctity and a place among the bhakti pantheon of sants; Eknath, even though a Brahman from a distinguished scholarly family, showed by his actions that there was equality among the true bhaktas. This paper will explore the thought and the actions of each bhakti figure in an attempt to determine their basic social and religious ideas, and then note the contemporary attempts to legitimize change through reference to these earlier religious figures. Chokhamela was born in the second half of the thirteenth century, prob- ably about the time that Dnyaneshwar, who is considered the founder of the bhakti sect in Maharashtra, was born. -

The Vithoba Temple of Pan<Jharpur and Its Mythological Structure

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 19S8 15/2-3 The Vithoba Faith of Mahara§tra: The Vithoba Temple of Pan<Jharpur and Its Mythological Structure SHIMA Iwao 島 岩 The Bhakti Movement in Hinduism and the Vithobd Faith o f MaM rdstra1 The Hinduism of India was formed between the sixth century B.C. and the sixth century A.D., when Aryan Brahmanism based on Vedic texts incor porated non-Aryan indigenous elements. Hinduism was established after the seventh century A.D. through its resurgence in response to non-Brah- manistic traditions such as Buddhism. It has continuously incorporated different and new cultural elements while transfiguring itself up to the present day. A powerful factor in this formation and establishment of Hinduism, and a major religious movement characteristic especially of medieval Hin duism, is the bhakti movement (a religious movement in which it is believed that salvation comes through the grace of and faith in the supreme God). This bhakti movement originated in the Bhagavad GUd of the first century B.C., flourishing especially from the middle of the seventh to the middle of the ninth century A.D. among the religious poets of Tamil, such as Alvars, in southern India. This bhakti movement spread throughout India through its incorporation into the tradition of Brahmanism, and later developed in three ways. First, the bhakti movement which had originated in the non-Aryan cul ture of Tamil was incorporated into Brahmanism. Originally bhakti was a strong emotional love for the supreme God, and this was reinterpreted to 1 In connection with this research, I am very grateful to Mr. -

SHRISAILEELA - JULY-AUGUEST-2005 English Section

SHRISAILEELA - JULY-AUGUEST-2005 English Section “Vithu-mauli, Sai-mauli” : Mrs. Mugdha Diwadkar Shree Dattatreya Sahasra Nama : Prof. Dr. K. J. Ajabia Shri Pant Maharaj as a Teacher : Naresh Dharwadkar In Sai’s Proximity : Mrs. Mugdha Diwadkar Is Baba Living & Helping now : Jyoti Ranjan SHREE SAI BABA SANSTHAN TRUST (SHIRDI) Management Committee Shri Jayant Murlidhar Sasane Shri Shankararao Genuji Kolhe Shri Bhausaheb Rajaram Wakchaure Chairman Vice-chairman Executive Officer This site is developed and maintained by Shri Saibaba Sansthan Trust. © Shri Saibaba Sansthan Trust, Shirdi. Homepage SHRISAILEELA - JULY-AUGUST-2005 Vithu-mauli, Sai-mauli Shree Dattatreya Sahasra Nama Shri Pant Maharaj as a Teacher In Sai’s Proximity Is Baba Living & Helping now “YOU ARE VITHU-MAULI*, YOU ARE SAI-MAULI !” — Mrs. Mugdha Diwadkar Preamble Pandurang of Pandharpur town is the Deity dear to many, not only from Maharashtra and Karnatak but also for several people from outside Maharashtra ! The heartfelt love of Vitthal pulls the devotees to Pandharpur - forgetting the differences in religions and castes. Due to this congregation, Pandharpur has become a regional cultural center. Many devotees fervently believe that Pandurang or Vitthal of Pandhari is Lord Shrikrishna. This Deity is a beautiful statue carved out of black stone. Actually, the complexion of Pandurang (Pandurang Kanti) is supposed to be fair and that’s why He is called ‘Pandu-rang’. However, at the time of Amrut Manthan, the poison ‘Halahal’ came out of the seven seas and Lord Shankar digested it. Therefore, Lord Shankar (and in turn Lord Vishnu) acquired a dark complexion. Similarly, Lord Vishnu took ‘Amrut’ and hence, Lord Shankar became fair like camphor (Karpoor Gaur). -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. Furtherowner. reproduction Further reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. HISTORICISM, HINDUISM AND MODERNITY IN COLONIAL INDIA By Apama Devare Submitted to the Faculty of the School of International Service of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In International Relations Chai Dean of the School of International Service 2005 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3207285 Copyright 2005 by Devare, Aparna All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3207285 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.