Religious Movements in Hindu Social Contexts: a Study of Paradigms for Contextual “Church” Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson. 8 Devotional Paths to the Divine

Grade VII Lesson. 8 Devotional paths to the Divine History I Multiple choice questions 1. Religious biographies are called: a. Autobiography b. Photography c. Hierography d. Hagiography 2. Sufis were __________ mystics: a. Hindu b. Muslim c. Buddha d. None of these 3. Mirabai became the disciple of: a. Tulsidas b. Ravidas c. Narsi Mehta d. Surdas 4. Surdas was an ardent devotee of: a. Vishnu b. Krishna c. Shiva d. Durga 5. Baba Guru Nanak born at: a. Varanasi b. Talwandi c. Ajmer d. Agra 6. Whose songs become popular in Rajasthan and Gujarat? a. Surdas b. Tulsidas c. Guru Nanak d. Mira Bai 7. Vitthala is a form of: a. Shiva b. Vishnu c. Krishna d. Ganesha 8. Script introduced by Guru Nanak: a. Gurudwara b. Langar c. Gurmukhi d. None of these 9. The Islam scholar developed a holy law called: a. Shariat b. Jannat c. Haj d. Qayamat 10. As per the Islamic tradition the day of judgement is known as: a. Haj b. Mecca c. Jannat d. Qayamat 11. House of rest for travellers kept by a religious order is: a. Fable b. Sama c. Hospice d. Raqas 12. Tulsidas’s composition Ramcharitmanas is written in: a. Hindi b. Awadhi c. Sanskrit d. None of these 1 Created by Pinkz 13. The disciples in Sufi system were called: a. Shishya b. Nayanars c. Alvars d. Murids 14. Who rewrote the Gita in Marathi? a. Saint Janeshwara b. Chaitanya c. Virashaiva d. Basavanna 1. (d) 2. (b) 3. (b) 4. (b) 5. (b) 6. (d) 7. -

THE COW in the ELEVATOR an Anthropology of Wonder the COW in the ELEVATOR Tulasi Srinivas

TULASI SRINIVAS THE COW IN THE ELEVATOR AN ANTHROPOLOGY OF WONDER THE COW IN THE ELEVATOR tulasi srinivas THE COW IN THE ELEVATOR An Anthropology of Won der Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2018 © 2018 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer ic a on acid-f ree paper ∞ Text designed by Courtney Leigh Baker Cover designed by Julienne Alexander Typeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Srinivas, Tulasi, author. Title: The cow in the elevator : an anthropology of won der / Tulasi Srinivas. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2017049281 (print) | lccn 2017055278 (ebook) isbn 9780822371922 (ebook) isbn 9780822370642 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822370796 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Ritual. | Religious life—H induism. | Hinduism and culture— India— Bangalore. | Bangalore (India)— Religious life and customs. | Globalization—R eligious aspects. Classification: lcc bl1226.2 (ebook) | lcc bl1226.2 .s698 2018 (print) | ddc 294.5/4— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2017049281 Cover art: The Hindu goddess Durga during rush hour traffic. Bangalore, India, 2013. FotoFlirt / Alamy. For my wonderful mother, Rukmini Srinivas contents A Note on Translation · xi Acknowl edgments · xiii O Wonderful! · xix introduction. WONDER, CREATIVITY, AND ETHICAL LIFE IN BANGALORE · 1 Cranes in the Sky · 1 Wondering about Won der · 6 Modern Fractures · 9 Of Bangalore’s Boomtown Bourgeoisie · 13 My Guides into Won der · 16 Going Forward · 31 one. ADVENTURES IN MODERN DWELLING · 34 The Cow in the Elevator · 34 Grounded Won der · 37 And Ungrounded Won der · 39 Back to Earth · 41 Memorialized Cartography · 43 “Dead- Endu” Ganesha · 45 Earthen Prayers and Black Money · 48 Moving Marble · 51 Building Won der · 56 interlude. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

Sant Dnyaneshwar - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Sant Dnyaneshwar - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Sant Dnyaneshwar(1275 – 1296) Sant Dnyaneshwar (or Sant Jñaneshwar) (Marathi: ??? ??????????) is also known as Jñanadeva (Marathi: ????????). He was a 13th century Maharashtrian Hindu saint (Sant - a title by which he is often referred), poet, philosopher and yogi of the Nath tradition whose works Bhavartha Deepika (a commentary on Bhagavad Gita, popularly known as "Dnyaneshwari"), and Amrutanubhav are considered to be milestones in Marathi literature. <b>Traditional History</b> According to Nath tradition Sant Dnyaneshwar was the second of the four children of Vitthal Govind Kulkarni and Rukmini, a pious couple from Apegaon near Paithan on the banks of the river Godavari. Vitthal had studied Vedas and set out on pilgrimages at a young age. In Alandi, about 30 km from Pune, Sidhopant, a local Yajurveda brahmin, was very much impressed with him and Vitthal married his daughter Rukmini. After some time, getting permission from Rukmini, Vitthal went to Kashi(Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh, India), where he met Ramananda Swami and requested to be initiated into sannyas, lying about his marriage. But Ramananda Swami later went to Alandi and, convinced that his student Vitthal was the husband of Rukmini, he returned to Kashi and ordered Vitthal to return home to his family. The couple was excommunicated from the brahmin caste as Vitthal had broken with sannyas, the last of the four ashrams. Four children were born to them; Nivrutti in 1273, Dnyandev (Dnyaneshwar) in 1275, Sopan in 1277 and daughter Mukta in 1279. According to some scholars their birth years are 1268, 1271, 1274, 1277 respectively. -

A Revolution in Kṛṣṇaism: the Cult of Gopāla Author(S): Norvin Hein Source: History of Religions , May, 1986, Vol

A Revolution in Kṛṣṇaism: The Cult of Gopāla Author(s): Norvin Hein Source: History of Religions , May, 1986, Vol. 25, No. 4, Religion and Change: ASSR Anniversary Volume (May, 1986), pp. 296-317 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1062622 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History of Religions This content downloaded from 130.132.173.217 on Fri, 18 Dec 2020 20:12:45 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Norvin Hein A REVOLUTION IN KRSNAISM: THE CULT OF GOPALA Beginning about A.D. 300 a mutation occurred in Vaisnava mythology in which the ideals of the Krsna worshipers were turned upside down. The Harivamsa Purana, which was composed at about that time, related in thirty-one chapters (chaps. 47-78) the childhood of Krsna that he had spent among the cowherds.1 The tales had never been told in Hindu literature before. As new as the narratives themselves was their implicit theology. The old adoration of Krsna as moral preceptor went into a long quiescence. -

Anekāntavāda and Dialogic Identity Construction

religions Article Anekantav¯ ada¯ and Dialogic Identity Construction Melanie Barbato Seminar für Religionswissenschaft und Interkulturelle Theologie, University of Münster, 48143 Münster, Germany; [email protected] Received: 1 November 2019; Accepted: 14 November 2019; Published: 20 November 2019 Abstract: While strong religious identity is often associated with violence, Jainism, one of the world’s oldest practiced religions, is often regarded as one of the most peaceful religions and has nevertheless persisted through history. In this article, I am arguing that one of the reasons for this persistence is the community’s strategy of dialogic identity construction. The teaching of anekantav¯ ada¯ allows Jainas to both engage with other views constructively and to maintain a coherent sense of self. The article presents an overview of this mechanism in different contexts from the debates of classical Indian philosophy to contemporary associations of anekantav¯ ada¯ with science. Central to the argument is the observation that anekantav¯ ada¯ is in all these contexts used to stabilize Jaina identity, and that anekantav¯ ada¯ should therefore not be interpreted as a form of relativism. Keywords: Jainism; anekantav¯ ada¯ ; identity; Indian philosophy; Indian logic 1. Introduction: Religious Identity and the Dialogic Uses of Anekantav¯ ada¯ Within the debate on the role of religion in public life, strong religious identity is often and controversially discussed within the context of violent extremism.1 Strong religion, as in the title of a book by Gabriel A. Almond, R. Scott Appleby and Emmanuel Sivan (Almond et al. 2003), is sometimes just another word for fundamentalism, with all its “negative connotations” (Ter Haar 2003, p. -

Religion in Modern India • Rel 3336 • Spring 2020

RELIGION IN MODERN INDIA • REL 3336 • SPRING 2020 PROFESSOR INFORMATION Jonathan Edelmann, Ph.D., University of Florida, Department of Religion, Anderson Hall [email protected]; (352) 392-1625 Office Hours: M,W,F • 9:30-10:30 AM or by appointment COURSE INFORMATION Course Meeting Time: Spring 2020 • M,W,F • Period 5, 11:45 AM - 12:35 PM • Matherly 119 Course Qualifications: 3 Credit Hours • Humanities (H), International (N), Writing (WR) 4000 Course Description: The modern period typically covers the years 1550 to 1850 AD. This course covers religion in India since the beginning of the Mughal empire in the mid-sixteenth century, to the formation of the independent and democratic Indian nation in 1947. The concentration of this course is on aesthetics and poetics, and their intersection with religion; philosophies about the nature of god and self in metaphysics or ontology; doctrines about non-dualism and the nature of religious experience; theories of interpretation and religious pluralism; and concepts of science and politics, and their intersection with religion. The modern period in India is defined by a diversity of religious thinkers. This course examines thinkers who represent the native traditions like Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism, as well as the ancient and classical traditions in philosophy and literature that influenced native religions in the modern period. Islam and Christianity began to interact with native Indian religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism during the modern period. Furthermore, Western philosophies, political theories, and sciences were also introduced during India’s modern period. The readings in this course focus on primary texts and secondary sources that critically portray and engage this complex and rich history of India’s modern period. -

Agnikarma in Ayurved: an Overview

International Journal of Science and Healthcare Research Vol.3; Issue: 1; Jan.-March 2018 Website: www.ijshr.com Review Article ISSN: 2455-7587 Agnikarma in Ayurved: An Overview Dnyaneshwar.K.Jadhav1, Dr.Sushilkumar Jangid2 1 2 Assistant Professor, Kayachikitsa Department, Assi.professor Agadtantra Department, Shri Dhanwantri Ayurvedic Medical College & Research Centre, India - 281401 Corresponding Author: Dnyaneshwar.K.Jadhav ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT the chapter of “DwiVraniyaChikitsa”. (2) Also AgniKarmaused in different Ayurveda is the everlasting supreme science of disease as follow – in Gulmachikitsa; (3) medicine because it deals with promotion of in bhagandar-chikitsaas taildagdha; (4) health and curing the diseases. The aim of in plihodar; (5) in arshachikitsa; (6) in Medical Science is to provide better health to visarpachikitsa; (7) in Arditchikitsa (8) every human being. To achieve this goal the In Sushruta Samhita: Sushruta pathy should be able to eliminate the disease and that to be without any side effects. mentioned the AgniKarma as supreme in Ayurveda have shaman and shodhan chikitsa. all the para surgical procedures. A Varity of medical procedure mentioned in separate chapter in Sutra-Sthana with Ayurved samh it as like ksharkarma, lepanam details about every aspect of etc. AgniKarmais one of the important AgniKarma, denotes its importance in proceduredescribed in Ayurveda. In this fast the treatment, during those period. lifestyle patients need instant result on all pain. Sushruta has referred Agni in AgniKarma is one of the fast procedure to Agropaharaniya, (9) as Upayantra, (10) reduced vedana (pain). Many samhitas have Anushstra (11) description of AgniKarma. From meaning to Ashtang Samgraha: Details indication, contraindication, its superiority all information included in charak, sushrut, Description of AgniKarma found in 40th vagbhat, har it as amhita. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

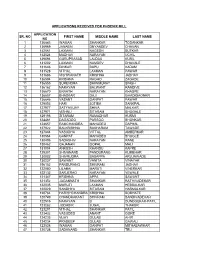

Applications Received for Phoenix Mill

APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FOR PHOENIX MILL APPLICATION SR. NO FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME LAST NAME NO 1 136843 WAMAN SHANKAR TODANKAR 2 136969 JANABAI DNYANDEV CHAVAN 3 142561 LAXMAN NAGESH BUTKAR 4 142524 MADHAV NARAYAN UCHIL 5 139594 GURUPRASAD LALDAS KURIL 6 131202 LAXMAN NAMDEV DHAVALE 7 131646 DINKAR BAPU KADAM 8 131528 VITHAL LAXMAN PAWAR 9 131686 VISHWANATH KRISHNA JADHAV 10 136594 KRISHNA RAGHO ZAGADE 11 136555 SURENDRA SHIWMURAT SINGH 12 136162 NARAYAN BALWANT RANDIVE 13 136670 EKNATH NARAYAN KHADPE 14 136657 BHASKAR DAJI GHADIGAONKR 15 136646 VASANT GANPAT PAWAR 16 129053 HARI JOTIBA SANKPAL 17 127977 SATYAVIJAY SHIVA MALKAR 18 127971 VISHNU SITARAM BHOGALE 19 129198 SITARAM RAMADHAR KURMI 20 124461 DAGADOO PARSOO BHONKAR 21 124657 RAMCHANDRA MAHADEO DAPHAL 22 127922 BALKRISHNA SAKHARAM TAWADE 23 127844 VASUDHA VITTAL AMBERKAR 24 130564 GANPAT MAHADEO BHOGLE 25 130496 SADASHIV NARAYAN RANE 26 130462 GAJANAN GOPAL MALI 27 131004 ANKUSH KHANDU KAPRE 28 129301 SHIVANAND PANDURANG KUMBHAR 29 130082 SHIVRUDRA BASAPPA ARJUNWADE 30 130237 SAWANT VANITA VINAYAK 31 196102 PANDURANG SHIVRAM JADHAV 32 122080 LILABAI MARUTI VINERKAR 33 122132 SARJERAO NARAYAN YEWALE 34 121347 KRISHNA APPA SAWANT 35 121352 JAGANNATH SHANKAR RATHIVADEKAR 36 122035 MARUTI LAXMAN HEBBALKAR 37 122029 SANDHYA SITARAM HARMALKAR 38 120784 HARISHCHANDRA KRISHNA BOBHATE 39 120749 CHANDRAKANT SHIVRAM BANDIVADEKAR 40 122516 NARAYAN B DUNDGEKAR-PATIL 41 123282 JODHBIR JUGAL THAKUR 42 123201 VITHAL SHANKAR PATIL 43 123432 VASUDEO ANANT GORE 44 124233 VIJAY GULAB AHIR 45 124234