Joodse Traditie Als Permanent Leren Abram, I.B.H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congregation Torah Ohr 19146 Lyons Road, Boca Raton, FL 33434 (561) 479-4049 ● ● [email protected] Rabbi Benjamin S

February 5 — 11, 2021 23 — 29 Shevat 5781 Congregation Torah Ohr 19146 Lyons Road, Boca Raton, FL 33434 (561) 479-4049 ● www.torahohrboca.org ● [email protected] Rabbi Benjamin S. Yasgur President, Jonas Waizer Office Hours Monday - Thursday 9:00am - 3:00pm, Friday 9:00am - 12noon WEEKDAY TIMES Earliest Davening (Fri-Thurs) 5:53am* Mishna Yomit (in Shul & online) 15 min. before Mincha Earliest Tallit/Tefillin (Fri-Thurs) 6:20am* Mincha/Ma’ariv (Shul & Tent) (S-Th) Shacharit at Shul (starting with Pesukai D’Zimra) 7:30am Shacharit in the Tent (starting with Pesukai D’Zimra) 8:30am Daven Mincha (S-Th) prior to 6:08pm Daf Yomi (online) 8:30am Repeat Kriat Shema after 6:46pm* Chumash Class (online) 9:30am *These are the latest times during the week BS”D CONGREGATION TORAH OHR NEW - UPDATED POLICIES FOR KEEPING OUR COMMUNITY SAFE We enjoy the seasonal return of our cherished congregants, friends, and neighbors. At the same time, let us acknowledge that the Corona-19 pandemic is not yet over. We cannot afford complacency in our sheltered senior community until the pandemic is fully controlled. Considering the situation of pikuach nefesh, the Shul will continue policies that protect all our members. We want you in Shul ASAP. But first, individuals returning to Florida, even from short out-of-state stays, must adhere to the CDC, Florida State and Shul rules: a) Self-isolate for 12 days; DO NOT ATTEND SHUL, including outdoor minyanim. If you have no symptoms after 12 days, please SHABBAT YITRO register to attend shul minyanim. -

Foreword, Abbreviations, Glossary

FOREWORD, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY The Soncino Babylonian Talmud TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH WITH NOTES Reformatted by Reuven Brauner, Raanana 5771 1 FOREWORDS, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY Halakhah.com Presents the Contents of the Soncino Babylonian Talmud TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH WITH NOTES, GLOSSARY AND INDICES UNDER THE EDITORSHIP OF R AB B I D R . I. EPSTEIN B.A., Ph.D., D. Lit. FOREWORD BY THE VERY REV. THE LATE CHIEF RABBI DR. J. H. HERTZ INTRODUCTION BY THE EDITOR THE SONCINO PRESS LONDON Original footnotes renumbered. 2 FOREWORDS, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY These are the Sedarim ("orders", or major There are about 12,800 printed pages in the divisions) and tractates (books) of the Soncino Talmud, not counting introductions, Babylonian Talmud, as translated and indexes, glossaries, etc. Of these, this site has organized for publication by the Soncino about 8050 pages on line, comprising about Press in 1935 - 1948. 1460 files — about 63% of the Soncino Talmud. This should in no way be considered The English terms in italics are taken from a substitute for the printed edition, with the the Introductions in the respective Soncino complete text, fully cross-referenced volumes. A summary of the contents of each footnotes, a master index, an index for each Tractate is given in the Introduction to the tractate, scriptural index, rabbinical index, Seder, and a detailed summary by chapter is and so on. given in the Introduction to the Tractate. SEDER ZERA‘IM (Seeds : 11 tractates) Introduction to Seder Zera‘im — Rabbi Dr. I Epstein INDEX Foreword — The Very Rev. The Chief Rabbi Israel Brodie Abbreviations Glossary 1. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

URJ Online Communications Master Word List 1 MASTER

URJ Online Communications Master Word List MASTER WORD LIST, Ashamnu (prayer) REFORMJUDAISM.org Ashkenazi, Ashkenazim Revised 02-12-15 Ashkenazic Ashrei (prayer) Acharei Mot (parashah) atzei chayim acknowledgment atzeret Adar (month) aufruf Adar I (month) Av (month) Adar II (month) Avadim (tractate) “Adir Hu” (song) avanah Adon Olam aveirah Adonai Avinu Malkeinu (prayer) Adonai Melech Avinu shebashamayim Adonai Tz’vaot (the God of heaven’s hosts [Rev. avodah Plaut translation] Avodah Zarah (tractate) afikoman avon aggadah, aggadot Avot (tractate) aggadic Avot D’Rabbi Natan (tractate) agunah Avot V’Imahot (prayer) ahavah ayin (letter) Ahavah Rabbah (prayer) Ahavat Olam (prayer) baal korei Akeidah Baal Shem Tov Akiva baal t’shuvah Al Cheit (prayer) Babylonian Empire aleph (letter) Babylonian exile alef-bet Babylonian Talmud Aleinu (prayer) baby naming, baby-naming ceremony Al HaNisim (prayer) badchan aliyah, aliyot Balak (parashah) A.M. (SMALL CAPS) bal tashchit am baraita, baraitot Amidah Bar’chu Amora, Amoraim bareich amoraic Bar Kochba am s’gulah bar mitzvah Am Yisrael Baruch atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech haolam, Angel of Death asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu Ani Maamin (prayer) Baruch She-Amar (prayer) aninut Baruch Shem anti-Semitism Baruch SheNatan (prayer) Arachin (tractate) bashert, basherte aravah bat arbaah minim bat mitzvah arba kanfot Bava Batra (tractate) Arba Parashiyot Bava Kama (tractate) ark (synagogue) Bava M’tzia (tractate) ark (Noah’s) Bavli Ark of the Covenant, the Ark bayit (house) Aron HaB’rit Bayit (the Temple) -

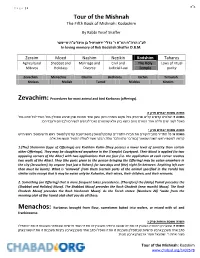

Tour of the Mishnah the Fifth Book of Mishnah: Kodashim

ב"ה P a g e | 1 Tour of the Mishnah The Fifth Book of Mishnah: Kodashim By Rabbi Yosef Shaffer לע"נ הרה"ח הוו"ח ר' גדלי' ירחמיא-ל בן מיכל ע"ה שייפער In loving memory of Reb Gedaliah Shaffer O.B.M. Zeraim Moed Nashim Nezikin Kodshim Taharos Agricultural Shabbat and Marriage and Civil and The Holy Laws of ritual Mitzvos Holidays Divorce Judicial Law Temple purity Zevachim Menachos Chullin Bechoros Erchin Temurah Kreisos Meilah Tamid Middos Kinnim Zevachim: Procedures for most animal and bird Korbanos (offerings). משנה מסכת זבחים פרק ה משנה ז: שלמים קדשים קלים שחיטתן בכל מקום בעזרה ודמן טעון שתי מתנות שהן ארבע ונאכלין בכל העיר לכל אדם בכל מאכל לשני ימים ולילה אחד המורם מהם כיוצא בהן אלא שהמורם נאכל לכהנים לנשיהם ולבניהם ולעבדיהם: משנה מסכת זבחים פרק י משנה א: כל התדיר מחבירו קודם את חבירו התמידים קודמין למוספין מוספי שבת קודמין למוספי ראש חדש מוספי ראש חדש קודמין למוספי ראש השנה שנאמר )במדבר כח( מלבד עולת הבקר אשר לעולת התמיד תעשו את אלה: 1.(The) Shelamim (type of Offerings) are Kodshim Kalim (they possess a lower level of sanctity than certain other Offerings). They may be slaughtered anywhere in the (Temple) Courtyard. Their blood is applied (to two opposing corners of the Altar) with two applications that are four (i.e. the application at each corner reaches two walls of the Altar). They (the parts given to the person bringing the Offering) may be eaten anywhere in the city (Jerusalem), by anyone (not just a Kohen), for two days and (the) night (in between. -

Adas Torah Journal of Torah Ideas

• NITZACHONניצחון Adas Torah Journal of Torah Ideas VOLUME 1:1 • PESACH - SHAVUOS 5774 • LOS ANGELES Nitzachon Adas Torah Journal of Torah Ideas Volume 1:1 Pesach – Shavuos 5774 Adas Torah 1135 South Beverly Drive Los Angeles, CA 90035 www.adastorah.org [email protected] (310) 228-0963 Rabbi Dovid Revah, Rav and Mara D’Asra Michael A. Horowitz, President Nitzachon Editorial Team Michael Kleinman, General Editor Yaakov Siegel, General Editor Penina Apter, Copy Editor Rabbi Andi Yudin, Copy Editor Rob Shur, Design and Layout www.rbscreative.com VOLUME 1:1 • PESACH - SHAVUOS 5774 דברי חכמים Rabbi Dovid Revah: Celebrating the Torah: Explaining the Special Nature of Seuda on Shavuos ..................................................................................... p. 13 Guest Contributor Rabbi Asher Brander: Erev Pesach, Matza, & Marriage: The Curious Halacha of Matza Non-Consumption ..................................................................................... p. 17 PESACH Dr. David Peto: Talmud Torah and Seder Night ..................................................................................... p. 37 Eli Snyder: Questions upon Questions: The Thematic Implications of the Mah Nishtana ..................................................................................... p. 47 Rabbi Yaakov Siegel: All of Nature is Miraculous or All Miracles are Natural: Opposing Views on Yetzias Mitzrayim ..................................................................................... p. 51 Yossi Essas: Arami Oved Avi .................................................................................... -

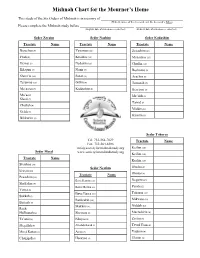

English Mishnah Chart

Mishnah Chart for the Mourner’s Home This study of the Six Orders of Mishnah is in memory of (Hebrew names of the deceased, and the deceased’s father) Please complete the Mishnah study before (English date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) (Hebrew date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) Seder Zeraim Seder Nashim Seder Kodashim Tractate Name Tractate Name Tractate Name Berachos (9) Yevamos (16) Zevachim (14) Peah (8) Kesubos (13) Menachos (13) Demai (7) Nedarim (11) Chullin (12) Kilayim (9) Nazir (9) Bechoros (9) Shevi’is (10) Sotah (9) Arachin (9) Terumos (11) Gittin (9) Temurah (7) Ma’asros (5) Kiddushin (4) Kereisos (6) Ma’aser Me’ilah (6) Sheni (5) Tamid (7) Challah (4) Middos (5) Orlah (3) Kinnim (3) Bikkurim (3) Seder Tohoros Tel: 732-364-7029 Tractate Name Fax: 732-364-8386 [email protected] Keilim (10) Seder Moed www.societyformishnahstudy.org Keilim (10) Tractate Name Keilim (10) Shabbos (24) Seder Nezikin Oholos (9) Eruvin (10) Tractate Name Oholos (9) Pesachim (10) Bava Kamma (10) Negaim (14) Shekalim (8) Bava Metzia (10) Parah (12) Yoma (8) Bava Basra (10) Tohoros (10) Sukkah (5) Sanhedrin (11) Mikvaos (10) Beitzah (5) Makkos (3) Niddah (10) Rosh HaShanah (4) Shevuos (8) Machshirin (6) Ta’anis (4) Eduyos (8) Zavim (5) Megillah (4) Avodah Zarah (5) Tevul Yom (4) Moed Kattan (3) Avos (5) Yadaim (4) Chagigah (3) Horayos (3) Uktzin (3) • Our Sages have said that Asher, son of the Patriarch Jacob sits at the opening to Gehinom (Purgatory), and saves [from entering therein] anyone on whose behalf Mishnah is being studied . -

Judges) “In All Your Gates” That They Are to Judge the People with Righteous Judgment

בייה PORTION DATE HEB DATE TORAH NEVIIM RENEWED Shoftim 18 Aug. 2018 7 Elul 5778 Deut. 16:18-21:9 Isa. 51:12-52:12 John 14:9-20 This week’s Torah portion starts with the qualification of shoftim (judges) “in all your gates” that they are to judge the people with righteous judgment. The Torah then describes how they are to judge against the accused. The Midrash questions the eligibility of judges. The immediate family of litigants are disqualified to judge as well as they are ineligible to testify as said, “The ahvot (fathers) shall not be put to death for the children, neither shall the children be put to death for the ahvot.” (Deut. 24:16) The Gemara interprets: fathers shall not be executed because of the testimony of sons, and vice versa.1 Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel (10 BCE-70 CE) said: Do not make light of justice, for it is one of the three legs of the world: justice, truth, and on peace. Therefore, we are to be mindful of not perverting justice as “you can cause the world to shake2 for it (justice) is one of the legs of Hashem’s Throne of Glory. “Righteousness and justice are the foundation of Your throne.” (Psa 85:15) The Proverbs 6:6-8 says, “Go to the ant, you lazy one; consider her halachot, and be wise: They have no guide, overseer, or ruler, yet she; Provides her food in the and gathers her food in the harvest.” The sages teach the ants has three stories in its home. -

©2015 Assaf Harel ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2015 Assaf Harel ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “THE ETERNAL NATION DOES NOT FEAR A LONG ROAD”: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF JEWISH SETTLERS IN ISRAEL/PALESTINE By ASSAF HAREL A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Anthropology Written under the direction of Daniel M. Goldstein And approved by ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “The Eternal Nation Does Not Fear A Long Road”: An Ethnography Of Jewish Settlers In Israel/Palestine By ASSAF HAREL Dissertation Director: Daniel M. Goldstein This is an ethnography of Jewish settlers in Israel/Palestine. Studies of religiously motivated settlers in the occupied territories indicate the intricate ties between settlement practices and a Jewish theology about the advent of redemption. This messianic theology binds future redemption with the maintenance of a physical union between Jews and the “Land of Israel.” However, among settlers themselves, the dominance of this messianic theology has been undermined by postmodernity and most notably by a series of Israeli territorial withdrawals that have contradicted the promise of redemption. These days, the religiously motivated settler population is divided among theological and ideological lines that pertain, among others issues, to the meaning of redemption and its relation to the state of Israel. ii This dissertation begins with an investigation of the impact of the 2005 Israeli unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip upon settlers and proceeds to compare three groups of religiously motivated settlers in the West Bank: an elite Religious Zionist settlement, settlers who engage in peacemaking activities with Palestinians, and settlers who act violently against Palestinians. -

Narratology, Hermeneutics, and Midrash

Poetik, Exegese und Narrative Studien zur jüdischen Literatur und Kunst Poetics, Exegesis and Narrative Studies in Jewish Literature and Art Band 2 / Volume 2 Herausgegeben von / edited by Gerhard Langer, Carol Bakhos, Klaus Davidowicz, Constanza Cordoni Constanza Cordoni / Gerhard Langer (eds.) Narratology, Hermeneutics, and Midrash Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Narratives from the Late Antique Period through to Modern Times With one figure V&R unipress Vienna University Press Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-8471-0308-0 ISBN 978-3-8470-0308-3 (E-Book) Veröffentlichungen der Vienna University Press erscheineN im Verlag V&R unipress GmbH. Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung des Rektorats der Universität Wien. © 2014, V&R unipress in Göttingen / www.vr-unipress.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk und seine Teile sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung in anderen als den gesetzlich zugelassenen Fällen bedarf der vorherigen schriftlichen Einwilligung des Verlages. Printed in Germany. Titelbild: „splatch yellow“ © Hazel Karr, Tochter der Malerin Lola Fuchs-Carr und des Journalisten und Schriftstellers Maurice Carr (Pseudonym von Maurice Kreitman); Enkelin der bekannten jiddischen Schriftstellerin Hinde-Esther Singer-Kreitman (Schwester von Israel Joshua Singer und Nobelpreisträger Isaac Bashevis Singer) und Abraham Mosche Fuchs. Druck und Bindung: CPI Buch Bücher.de GmbH, Birkach Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier. Contents Constanza Cordoni / Gerhard Langer Introduction .................................. 7 Irmtraud Fischer Reception of Biblical texts within the Bible: A starting point of midrash? . 15 Ilse Muellner Celebration and Narration. Metaleptic features in Ex 12:1 – 13,16 . -

Haggadah B'chol Dor Va-Dor (Full)

Haggadah B’chol Dor Va-Dor A Haggadah for all Generations Edited by Rabbi Dr Andrew Goldstein and Rabbi Pete Tobias Designed by Tammy Kustow Dedicated to Rabbi Dr Sidney Brichto 1936-2009 London 2010/5770 iii ii Introduction Acknowledgements Pesach First and foremost, we must acknowledge our debt to Tammy Kustow, whose skill and patience as our designer are worthy of more recognition than will be gained by The origins of Pesach are to be found far back in antiquity, in two separate but these few words. Thanks also to members of Liberal Judaism’s Rabbinic Conference connected spring festivals: a pastoral celebration by shepherds of the lambing who offered suggestions and advice; in particular Rabbis Rachel Benjamin, Janet season, and an agricultural celebration by farmers of the year’s first grain harvest. Burden, David Goldberg and Mark Solomon. Ann and Bob Kirk made valuable This dual connection with nature is reflected in the festival’s two earliest names: suggestions on the content and at the proof reading stage. Chag ha-Pesach – the Festival of the Paschal Lamb, and Chag ha-Matzot – the Festival of Unleavened Bread. Our thanks are also due to the numerous contributors to this Haggadah for their artwork, poetry and other material. Full details can be found in the notes on the Some time after the Exodus from Egypt, which most scholars date in the 13th Liberal Judaism website (www.liberaljudaism.org/haggadah). century BCE, these two nature celebrations were unified in a single festival and their meaning reinterpreted religiously, in the light of the most significant event in Jewish We would particularly like to thank Joe Buchwald Gelles at haggadahsrus.com and history, the Exodus. -

Abbreviations

Abbreviations 1. Source Indications Names of biblical books, Apocrypha, Pseudepigrapha and Qumran writings are abbreviated according to the usage of the Journal of Biblical Literature (see JBL 95 [1976] 334f.). For Philo's works the usage of the Loeb edition is followed. For rabbinic literature see following list: Ah. Ahilut Ar. Arakhin A.R.N. alb Avot de-Rabbi Natan, version A/B Av. Zar. Avoda Zara Bava K./M./B. Bava Kamma/Metsia/Batra Bekh. Bekhorot Ber. Berakhot Bikk. Bikkurim B.T. Babylonian Talmud Cant. R. Canticles Rabba Dem. Demai Deut. R. Deuteronomy Rabba Eccl. R. Ecclesiastes Rabba Ed. Eduyot Er. Eruvin Exod. R. Exodus Rabba Gen. R. Genesis Rabba Gitt. Gittin Hag. Hagiga Hor. Horayot Hull. Hull in Kel. Kelim Ker. Keritot Ket. Ketubbot Kidd. Kiddushin Kil. Kilayim 411 ABBREVIATIONS Kinn. Kinnim Lam. R. Lamentations Rabba Lev. R. Leviticus Rabba M. Mishna Maasr. Maasrot Maas. Sh. Maaser Sheni Makhsh. Makhshirin Makk. Makkot Meg. Megill a Meg. Taan. Megillat Taanit Mekh. Mekhilta (de-R. Yishmael) Mekh. de-R. Sh.b.Y. Mekhilta de-R. Shimon ben Yohai Men. Menahot Midr. ha-Gad. Midrash ha-Gadol Midr. Prov. Midrash Proverbs Midr. Ps. Midrash Psalms (Shohar Tov) Midr. Tann. Midrash Tannaim Mikw. Mikwaot Moed K. Moed Katan Naz. Nazir Ned. Nedarim Neg. Negaim Num. R. Numbers Rabba Oh. Ohalot Pes. Pesahim Pes. R. Pesikta Rabbati Pes. de-R.K. Pesikta de-Rav Kahana Pirkei de-R. El. Pirkei de-R. Eliezer P.T. Palestinian Talmud Rosh H. Rosh ha-Shana S.E.R. Seder Eliyahu Rabba S.E.Z. Seder Eliyahu Zutta Sanh.