In the Shadow of Nuremberg: the Creation of the Yokohama Trials of Class B and C War Criminals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unclass\F\ED UNCLASSIFIED

• . ' UNClASS\f\ED I . J UNCLASSIFIED RAID AT LOS BANOS by Maxwell C. Bailey, MAJ, USAF Section 15 Arter-Darby Military History Writing Award Lf B lJS • CGSC FT. LEAVENWORTH, KS ,, - p , 8 1989 ACCE SION W. --~~- PO REGISTER ______ RAID AT LOS BANOS The American experience in rescuing its prisoners-of-war (P.O.W.s) and political hostages has been marked with failure and often disaster. ,. In reviewing our experience, most people remember the Son Tay raid, the Mayaquez incident, and the Iranian hostage attempt but overlook our one notable success. On 23 February 1945, elements of the 11th Airborne Division conducted a combined parachute assault, amphibious landing, and diversionary ground attack to rescue over 2,100 civilian internees held by the Japanese at Los Banos, Luzon, Philippine Islands. This mission provides an excellent opportunity to consider some key elements of the prisoner rescue mission. 11th Airborne Divi~ion: Nasugbu to Manila On 31 January 1945, the 11th Airborne Division, commanded by Major General Joseph M. Swing, made an amphibious assault at Nasugbu, Luton, 45 miles south of Manila (Map A). At the time of the assault, the 11th Airborne was under the command of the Eighth U.S. Army. The assault for ces consisted of the 11th Airborne Division's own 187th and 188th Glider Infantry Regiments reinforced by two battalions from the 19th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division. The 11th's other organic regiment, the 511th Parachute Infantry, was in reserve on Mindoro. The landing forces moved inland against light resistance toward the Division's initial objective, Tagaytay Ridge. -

Hall's Manila Bibliography

05 July 2015 THE RODERICK HALL COLLECTION OF BOOKS ON MANILA AND THE PHILIPPINES DURING WORLD WAR II IN MEMORY OF ANGELINA RICO de McMICKING, CONSUELO McMICKING HALL, LT. ALFRED L. McMICKING AND HELEN McMICKING, EXECUTED IN MANILA, JANUARY 1945 The focus of this collection is personal experiences, both civilian and military, within the Philippines during the Japanese occupation. ABAÑO, O.P., Rev. Fr. Isidro : Executive Editor Title: FEBRUARY 3, 1945: UST IN RETROSPECT A booklet commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Liberation of the University of Santo Tomas. ABAYA, Hernando J : Author Title: BETRAYAL IN THE PHILIPPINES Published by: A.A. Wyn, Inc. New York 1946 Mr. Abaya lived through the Japanese occupation and participated in many of the underground struggles he describes. A former confidential secretary in the office of the late President Quezon, he worked as a reporter and editor for numerous magazines and newspapers in the Philippines. Here he carefully documents collaborationist charges against President Roxas and others who joined the Japanese puppet government. ABELLANA, Jovito : Author Title: MY MOMENTS OF WAR TO REMEMBER BY Published by: University of San Carlos Press, Cebu, 2011 ISBN #: 978-971-539-019-4 Personal memoir of the Governor of Cebu during WWII, written during and just after the war but not published until 2011; a candid story about the treatment of prisoners in Cebu by the Kempei Tai. Many were arrested as a result of collaborators who are named but escaped punishment in the post war amnesty. ABRAHAM, Abie : Author Title: GHOST OF BATAAN SPEAKS Published by: Beaver Pond Publishing, PA 16125, 1971 This is a first-hand account of the disastrous events that took place from December 7, 1941 until the author returned to the US in 1947. -

The Palawan Massacre

CATALYST FOR ACTION The Palawan Massacre Michael E. Krivdo 35 | VOL 14 NO 1 fter three years of brutal captivity under the Despite these precautions, word spread quickly as evidence Japanese, the 150 American inmates of prisoner of of the incident and others just as grisly. Leaders decided to A war (POW) Camp 10-A on the western Philippine act and to rescue prisoners, detainees, and internees from island of Palawan had developed an instinct for similar fates. recognizing the abnormal. For several months in late 1944 On that fateful morning of 14 December the guards the Palawan POWs had worked hard to build a runway for roused the prisoners at 0200 hours, far earlier than normal. the Japanese Army. Lately, their duties included repairing At the airfield before work the POWs saw more guards damage caused by almost daily U.S. bombing attacks.1 than usual. Many chalked it up to pre-invasion jitters As 1944 came to an end, many of the prisoners noticed because the Allies had been bombing Japanese bases in changes in the demeanor of their guards. The Japanese preparation of an invasion. The laborers were ordered had become increasingly short-tempered and imposed to repair damage and improve the airstrip. As he was cruel punishments for the slightest of infractions. On the working to fill a bomb crater, Marine Corporal (CPL) Rufus morning of 14 December 1944, the POWs’ sense of dread W. Smith turned to his long-time friend, CPL Glenn W. reached new heights.2 McDole, and said, “Something is going on, Dole. -

T. Harry Williams Center for Oral History Collection ABSTRACT INTERVIEWEE NAME: Joseph Emile Dupont, Jr. COLLECTION: 4700.1409

T. Harry Williams Center for Oral History Collection ABSTRACT INTERVIEWEE NAME: Joseph Emile Dupont, Jr. COLLECTION: 4700.1409 IDENTIFICATION: Louisiana native, served in World War II with the U.S. Marine Corps, was a prisoner of the Japanese in the Philippines. INTERVIEWER: Jennifer Abraham SERIES: Military INTERVIEW DATES: Session I - February 14, 2001; Session II - April 26, 2001; Session III - May 11, 2001; Session IV - June 19, 2001; Session V - September 5, 2001; Session VI - January 29, 2002. FOCUS DATES: Sessions I -V: 1940-1945 Session VI: 1920s-1940s ABSTRACT: Session I Tape 2037, Side A Dupont born February 2, 1922, in Plaquemine, Louisiana; family background; transferred from Catholic to public school to participate in athletics; involvement with football, track, and boxing; graduated in 1940, during the Great Depression; jobs were scarce; father worked in distribution for Texaco; inspired to join Marine Corps after seeing movie starring Dick Powell; meeting an army convoy en route to Fort Polk; went to Marine recruitment office in New Orleans; despite worries about flat feet and being too short, accepted into Marine Corps; had to board train bound for San Diego that night; boot camp drilling and discipline; methods of firing rifle; test on marksmanship; rifle training; graduation from boot camp; everybody friendly with drill instructors after graduation; boarded USS Chaumont, bound for Asia; stop en route in Vallejo, California; getting drunk on Cuba Libres during liberty in Vallejo; departing California; description of ship; -

Download Print Version (PDF)

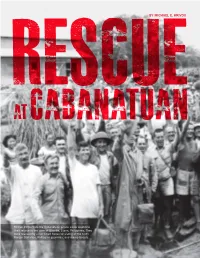

BY MICHAEL E. KRIVDO Former POWs from the Cabanatuan prison camp celebrate their rescue in the town of Guimba, Luzon, Philippines. They were rescued by a combined force consisting of the Sixth Ranger Battalion, Philippine guerrillas, and Alamo Scouts. 43 | VOL 14 NO 2 n 6 May 1942, Lieutenant General (LTG) Jonathan internees in the Philippines. They were to establish contact M. ‘Skinny’ Wainwright IV surrendered the last with them and report. This information would be used to OAmerican forces in the Philippines to the Imperial develop rescue plans.3 Japanese Army. With that capitulation more than 23,000 In late 1944, reports of the Palawan POW Camp American servicemen and women, along with 12,000 Massacre traveled quickly to SWPA (see article in previous Filipino Scouts, and 21,000 soldiers of the Philippine issue). The initial information came from the guerrillas Commonwealth Army became prisoners of war (POWs).1 who assisted survivors after escaping. The horrific details To add to the misfortune, about 20,000 American citizens, prompted SWPA to dispatch amphibian aircraft to recover many of them wives and children of the soldiers posted the escapees. Once in Australia, eyewitness accounts of the to the Philippines, were also detained and placed in mass execution caused military leaders to swear to prevent internment camps where they were subjected to hardship other atrocities. Thousands of other prisoners were still for years. Tragically, of all the American prisoners in held by the Japanese, including the thousand or so still World War II, the POWs in the Philippines suffered one believed held at Cabanatuan, on Luzon Island.4 of the highest mortality rates at 40 percent. -

Activity: We Did Not Surrender: the POW Experience in the Philippines

Activity: We Did Not Surrender: The POW Experience in the Philippines Guiding question: How did American prisoners of war survive the war in the Pacific? DEVELOPED BY NICOLE WINTER Grade Level(s): 9-12 Subject(s): Social Studies Cemetery Connection: Manila American Cemetery, San Francisco National Cemetery Fallen Hero Connection: Private Evans Overbey, Lieutant Colonel Charles Leinbach Activity: We Did Not Surrender: The POW Experience in the Philippines 1 Overview Using primary sources from Pacific Theater veterans includ- ing memoirs, testimonies, and photographs, students will investigate the capture, camp experience, and means of survival of prisoners of war at the Cabanatuan POW Camp in “Private Evans Overbey the Philippines. experienced the horrors of the Bataan Death March and succumbed to the poor Historical Context conditions of the prisoner The Third Geneva Convention established international rules of war (POW) camp at for the treatment of prisoners of war in 1929. However, after Cabanatuan, Philippines. the Japanese attacked the Philippines in December 1941 This lesson offers personal and took control of the islands in April 1942, they forced connections to the POW experience in the Pacific Allied soldiers to march across the Bataan Peninsula with through my Fallen Hero, as little water, food, or rest in the hot, tropical climate of the well as other camp survivors. Philippines. Some stragglers that could not keep up on the Though little is known about march were executed at point blank range by the Japanese. Overbey before the war, it Approximately 75,000 Americans and Filipinos were forced is important to recognize on the Bataan Death March. -

Assuming Rape: the Reproduction of Fear in American Military Female Pows William Junior Hillius a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fu

Assuming Rape: The Reproduction of Fear in American Military Female POWs William Junior Hillius A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies University of Washington 2012 Committee: Dr. Emily Noelle Ignacio Dr. David Coon Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Tacoma Table of Contents Introduction: Your Mother wears Combat Boots……………………………………..………..6 Overview………………………………………………………………….……...7 The Vulnerable White Woman……………………………………………….…..8 The Military and Women………………………………………………………..10 The Evolution of Gender and the Media………………………………………...10 Women in the Military...................................................................................…....12 POWs in General…………………………………………………………………15 Women as POWs…………………………………………………………………16 Methods and General Findings…………………………………………………...18 The Importance of Analyzing the Discourse of Rape……………………………19 The Role of the Media……………………………………………………………19 Summary of Chapters…………………………………………………………….20 Chapter I: Captured Women: A Historical Background of American Military Female POWs. 22 Overview……………………………………………………………………….….23 Guam: 10 December 1941…………………………………………………………27 Near Baguio Philippines 28 December 1941………………………………………28 Manila Philippines 03 January 1942……………………………………………….30 Corregidor Philippine 06 May 1942………………………………………………..31 Mindanao Philippines 10 May 1942………………………………………………..35 Aachen Germany 27 September 1944……………………………………………...36 The Interim Years 1946-1991………………………………………………………37 -

World War II Prisoners of the Japanese Data Files

National Archives and Records Administration 860 I Adelphi Road College Park, Maryland 20740-6001 List of Documentation World War II Prisoners of the Japanese NN3-ADBC-08-001 (NWME) Records of the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor (ADBC) (Donated Materials Group ADBC) N.ARA Prepared Documentation Pages List of Documentation ....................................................................... 1 User Note ...................................................................................... 2 Donor Documentation Narrative........................................................................................ 2 Abbreviations/Codes & Meanings for Rank Field ...................................... 5 Abbreviations/Codes & Meanings for Arm Field......................................... I Codes & Meanings for Source 1, Source 2, and Source 3 Fields ...................... 2 Abbreviations/Codes & Meanings for Subordinate Unit Field .........................9 Abbreviations/Codes & Meanings for Assigned Unit Field ............................ 7 Abbreviations/Codes & Meanings for Parent Unit Field ................................ I Supplemental Donor Documentation* Supplemental User Note 3 ................................................................... 2 Supplemental User Note I ................................................................... 3 User Note ..................................................................................... 2 Introduction Letter .......................................................................... -

Massacre at Palawan World War II the Original Detailed Accounts - As Written by V

Massacre at Palawan World War II The Original Detailed Accounts - as written by V. Dennis Wrynn With the stunning defeats suffered by the United States, Great Britain and the Netherlands in the early months of the Pacific War, thousands of Allied military personnel became prisoners of the Japanese. The Americans captured in the Philippines were initially detained in filthy, overcrowded POW camps near Manila, but eventually most were shipped to other parts of the Japanese empire as slave laborers. Puerto Princesa, Palawan Island in the Philippines Among the American prisoners remaining in the Philippines were 346 men who were sent 350 miles on August 1, 1942, from the Cabanatuan POW camps north of Manila, and from Bilibid Prison in Manila itself, to Puerto Princesa on the island of Palawan. Palawan is on the western perimeter of the Sulu Sea, and the POWs were shipped there to build an airfield for their captors. Although the prisoners' numbers fluctuated throughout the war, the brutal treatment they received at the hands of their Japanese guards was always the same. The men were beaten with pick handles, and kickings and slappings were regular daily occurrences. Prisoners who attempted to escape were summarily executed. The Palawan compound was known as Camp 10-A, and the prisoners were quartered in several unused Filipino constabulary buildings that were sadly dilapidated. Food was minimal; each day, prisoners received a mess kit of wormy Cambodian rice and a canteen cup of soup made from camote (a Philippine variant of sweet potatoes) vines boiled in water. Prisoners who could not work had their rations cut by 30 percent. -

Findings of the War Crimes Tribunal

DOCUMENTARY MILITARY AND CIVILIAN PRISONERS OF WAR UNDER THE JURISDICTION OF THE IMPERIAL JAPANESE ARMY ATROCITIES--SEVERE MISTREATMENT--SLAVE LABOR 1931-1945 COMPILED AND NARRATED BY EDWARD JACKFERT PAST NATIONAL COMMANDER AMERICAN DEFENDERS OF BATAAN & CORREGIDOR, INC. International Military Tribunal For The Far East Gathers War Crimes Evidence Against Japanese Armed Forces FINDINGS OF THE WAR CRIMES TRIBUNAL Altogether, over 5,000 Japanese civilian and military personnel were arrested for the caculated repreisals of state and individual acts of brutality which had taken over a half million Asiatics and Westerners. Most of those apprehended had committed crimes against Western nationals, who represented less than a tenth of the victims. About 4,000 of the suspects of brutality were brought to trial. Of the 4,000, some 800 were acquitted, some 2,400 were sentenced to three years or more impisonment, and 809 were executed. Tojo and seven of his ruling hierarchy were sentenced to hang. Generals Yamashita and Homma were tried by the War Crimes Tribunal in Manila. Yamashita was found guilty of permitting brutal atrocities at the end of the war in the Philippines. Among the major charges against him were responsibility for the brutalities at Pasay School and the Palawan Massacre, as well as widespread slaughter of Filipino men and women in Manila. General Homma was charged for being responsible for Japanese actions as the beginning of the war-----the Bataan Death March and Camp O’Donnell. So as the U.S. war crimes process ended---except those condemned to death---the severest punishment for those found guilty of the most cruel and savage acts, was 13 years in prison. -

The Round Tablette Founding Editor: James W

The Round Tablette Founding Editor: James W. Gerber, MD (1951–2009) Thursday, 26 October 2017 and could be treated as such. The savage bru- 31:03 Volume 31 Number 3 tality that characterized Japanese treatment of Published by WW II History Round Table American prisoners throughout the war was Written by Drs. Connie Harris & Chris Simer first experienced on the Death March. www.mn-ww2roundtable.org Beatings, lack of water in the tropical heat, and Welcome to the second October meeting of death by bayonet for those who fell behind shocked the American forces in Japanese the Dr. Harold C. Deutsch World War II hands. If civilians offered the prisoners water History Round Table. Tonight’s speaker is or food, they were killed. This nightmare Stephen Moore, author of Pacific Payback and march was only be the beginning of the suffer- As Good As Dead. He will discuss the prisoner ing of the American POWs, many of whom of war camp at Palawan, the site of a massacre became laborers for Japanese military projects of American servicemen. and in factories and mines in Japan. On December 8, 1941, the Japanese destroyed In August 1942, the Japanese decided to use American air assets in the Philippines and invad- POWs as slave labor building an airfield on ed the main island of Luzon, beginning their Palawan, an island southwest of Luzon. march toward the capital of Manila. By the end Roughly four hundred POWS were taken from of December, Allied forces had retreated to the camps near Manila and brought to Palawan’s Bataan Peninsula and commanding General capital of Puerto Princesa. -

Rao Bulletin 1 Jun 2021

RAO BULLETIN 1 JUN 2021 PDF Edition THIS RETIREE ACTIVITIES OFFICE BULLETIN CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Pg Article Subject . * DOD * . 04 == DoD Nuclear Mission [03] ---- (Ten Year Modernization Cost Jumps to $634B) 05 == NPRC Military Records [09] ---- (Rep. Davidson Speaks on Center’s Nonperformance) 06 == NPRC Military Records [10] ---- (NARA Calls In DoD To Help Resolve Its Backlog) 08 == DoD Fraud, Waste, & Abuse ---- (Reported MAY 01 thru 31, 2021) 09 == U.S. Capitol Riot [14] ---- (Quantico Marine Major Warnagir Charged) 10 == U.S. Capitol Riot [15] ---- (Capitol National Guard Protection Cost to Date $520M+) 11 == TRICARE Dental Program [20] ---- (Slight Premium Increase Begins in May) 13 == Arlington National Cemetery [92] ---- (Eligibility Could Change Soon) 14 == POW/MIA [128] ---- (Agency Wants to Disinter 'Unknown' From Punchbowl) 17 == POW/MIA Recoveries & Burials ---- (Reported 01 thru 31 MAY 2021 | Twenty-Four) . * VA * . 21 == VA Cemeteries [24] ---- (All Restrictions on Cemetery Visits Lifted Ahead Of Memorial Day) 22 == VA Cybersecurity [01] ---- (How Secure Is Veterans’ Data?) 23 == VA Toxic Exposure Care ---- (Addition of 3 AO Presumptive Conditions to Begin) 25 == VA Covid-19 Vaccines [04] ---- (Overseas Vets to be Reimbursed – Not Provided) 26 == VA Covid-19 Vaccines [05] ---- (Overseas Reimbursement Procedure) 27 == Covid-19 Headgear [18] ---- (Respiratory Helmet in Use at Hines VAMC) 28 == VA FMP [06] ---- (Medical Claims Abroad) 30 == VA Herbicide Related Claims ---- (Previously Denied Vet & Survivor Ones to be Readjudicated) 30 == VA Dizziness Care ---- (Investigating and Treating Services Available from VA Audiology) 31 == VA Caregiver Program ---- [72] ---- (After Court Ruling VA Overhauls Application Process) 33 == Hepatitis C [06] ---- (If Enrolled at VA Test Is Available upon Request) 1 33 == VA Fraud, Waste & Abuse ---- (Reported MAY 01 thru 31.