Download Print Version (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

America's Rangers

America’s Rangers: The Story of America’s First Warriors and their Journey from Tradition to Institution by James Sandy, B.A. A Thesis In HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Dr. John R. Milam Chair of Committee Dr. Laura Calkins Dr. Barton Myers Peggy Gordon Miller Dean of the Graduate School August, 2011 Copyright 2011, James Sandy Texas Tech University, James Sandy, Summer 2011 Acknowledgments This work would not have been possible without the constant encouragement and tutelage of my committee. They provided the inspiration for me to start this project, and guided me along the way as I slowly molded a very raw idea into the finished product here. Dr. Laura Calkins witnessed the birth of this project in my very first graduate class and has assisted me along every step of the way as a fantastic proofreader and a wonderful sounding board where many an idea was first verbalized. Dr. Calkins has been and will continue to be invaluable mentor and friend throughout my graduate education. Dr. Barton Myers was the latest addition to my committee, but he pushed me to expand my project further back into American History. The vast scope that this work encompasses proved to be my biggest challenge, but has come out as this works’ greatest strength. I cannot thank Dr. Myers enough for pushing me out of my comfort zone. Dr. Ron Milam has been a part of my academic career from the beginning and has long served as my inspiration in pursuing a life in academia. -

World War Ii in the Philippines

WORLD WAR II IN THE PHILIPPINES The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 Copyright 2016 by C. Gaerlan, Bataan Legacy Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. World War II in the Philippines The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 By Bataan Legacy Historical Society Several hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Philippines, a colony of the United States from 1898 to 1946, was attacked by the Empire of Japan. During the next four years, thou- sands of Filipino and American soldiers died. The entire Philippine nation was ravaged and its capital Ma- nila, once called the Pearl of the Orient, became the second most devastated city during World War II after Warsaw, Poland. Approximately one million civilians perished. Despite so much sacrifice and devastation, on February 20, 1946, just five months after the war ended, the First Supplemental Surplus Appropriation Rescission Act was passed by U.S. Congress which deemed the service of the Filipino soldiers as inactive, making them ineligible for benefits under the G.I. Bill of Rights. To this day, these rights have not been fully -restored and a majority have died without seeing justice. But on July 14, 2016, this mostly forgotten part of U.S. history was brought back to life when the California State Board of Education approved the inclusion of World War II in the Philippines in the revised history curriculum framework for the state. This seminal part of WWII history is now included in the Grade 11 U.S. history (Chapter 16) curriculum framework. The approval is the culmination of many years of hard work from the Filipino community with the support of different organizations across the country. -

Ranger Handbook) Is Mainly Written for U.S

SH 21-76 UNITED STATES ARMY HANDBOOK Not for the weak or fainthearted “Let the enemy come till he's almost close enough to touch. Then let him have it and jump out and finish him with your hatchet.” Major Robert Rogers, 1759 RANGER TRAINING BRIGADE United States Army Infantry School Fort Benning, Georgia FEBRUARY 2011 RANGER CREED Recognizing that I volunteered as a Ranger, fully knowing the hazards of my chosen profession, I will always endeavor to uphold the prestige, honor, and high esprit de corps of the Rangers. Acknowledging the fact that a Ranger is a more elite Soldier who arrives at the cutting edge of battle by land, sea, or air, I accept the fact that as a Ranger my country expects me to move further, faster, and fight harder than any other Soldier. Never shall I fail my comrades I will always keep myself mentally alert, physically strong, and morally straight and I will shoulder more than my share of the task whatever it may be, one hundred percent and then some. Gallantly will I show the world that I am a specially selected and well trained Soldier. My courtesy to superior officers, neatness of dress, and care of equipment shall set the example for others to follow. Energetically will I meet the enemies of my country. I shall defeat them on the field of battle for I am better trained and will fight with all my might. Surrender is not a Ranger word. I will never leave a fallen comrade to fall into the hands of the enemy and under no circumstances will I ever embarrass my country. -

The Philippine Army World War II

The Philippine Army World War II The commonwealth of the Philippines was governed on the structure of outmoded strategies of former colonial governments. New goals included the development of an independent military force, was widely scattered and inadequate. The United States government in principal provided token support until the threat of war surfaced. The recruiting and funding of the Philippine Scouts was under the jurisdiction of the United States, resulted in the establishment and foundation of The Philippine Army. President Delano Roosevelt of the United States commissioned General Douglas MacArthur, to become the mentor of the infant military force. The appointment was withdrawn, caused by internal colonial American petty political dissention and jealousies. MacArthur retired from American military service in 1937 to accept the Baton of Field Marshall, of the Philippines, by an Act of the commonwealth government to retain the General's services. General MacArthur had envisioned the growing threat of war in the far-east. He addressed his underlying concept which called for the full support of Commonwealth government and instilled upon President Manuel Quezon to guard against the probable menace. The young nation was practically defenseless in 1947 to cope with threat that within five years became a reality. Under MacArthur’s expertise and direction were implemented the insurmountable plans for the defense of hundreds of islands in the archipelago. On July 27, 1941, war clouds were brewing, and the retired General was recalled to active American military service this time to energize and muster the infant Philippine Army. By this act, the United States was concerned in the continued sovereignty of the Philippines. -

Unclass\F\ED UNCLASSIFIED

• . ' UNClASS\f\ED I . J UNCLASSIFIED RAID AT LOS BANOS by Maxwell C. Bailey, MAJ, USAF Section 15 Arter-Darby Military History Writing Award Lf B lJS • CGSC FT. LEAVENWORTH, KS ,, - p , 8 1989 ACCE SION W. --~~- PO REGISTER ______ RAID AT LOS BANOS The American experience in rescuing its prisoners-of-war (P.O.W.s) and political hostages has been marked with failure and often disaster. ,. In reviewing our experience, most people remember the Son Tay raid, the Mayaquez incident, and the Iranian hostage attempt but overlook our one notable success. On 23 February 1945, elements of the 11th Airborne Division conducted a combined parachute assault, amphibious landing, and diversionary ground attack to rescue over 2,100 civilian internees held by the Japanese at Los Banos, Luzon, Philippine Islands. This mission provides an excellent opportunity to consider some key elements of the prisoner rescue mission. 11th Airborne Divi~ion: Nasugbu to Manila On 31 January 1945, the 11th Airborne Division, commanded by Major General Joseph M. Swing, made an amphibious assault at Nasugbu, Luton, 45 miles south of Manila (Map A). At the time of the assault, the 11th Airborne was under the command of the Eighth U.S. Army. The assault for ces consisted of the 11th Airborne Division's own 187th and 188th Glider Infantry Regiments reinforced by two battalions from the 19th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division. The 11th's other organic regiment, the 511th Parachute Infantry, was in reserve on Mindoro. The landing forces moved inland against light resistance toward the Division's initial objective, Tagaytay Ridge. -

Cabanatuan Memorial GPS N15 30.576 E121 2.669 Cabanatuan Memorial American Battle Monuments Commission

Cabanatuan Memorial GPS N15 30.576 E121 2.669 Cabanatuan Memorial American Battle Monuments Commission The Cabanatuan Memorial is about 4.5 miles Northeast of Cabanatuan City, situated on the south side of the Nueva Ecija-Aurora Road. American Battle Monuments Commission This agency of the United States government operates and maintains 25 American cemeteries and 27 memorials, monuments and markers in 16 countries. The Commission works to fulfill the vision of its first chairman, General of the Armies John J. Pershing. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I, promised that “time will not dim the glory of their deeds.” American Battle Monuments Commission 2300 Clarendon Boulevard, Suite 500 Arlington, VA 22201 USA Manila American Cemetery McKinley Road Global City, Taguig Republic of Philippines tel 011-632-844-0212 email [email protected] gps N14 32.483 E121 03.008 For more information on this site and other ABMC commemorative sites, please visit: www.abmc.gov Cabanatuan Memorial Filipino guerrillas provided The Cabanatuan Memorial, 85 miles north of Manila, honors reconnaissance, operated those who died there when it was a Japanese prisoner of war road blocks, and performed other essential missions on camp. Approximately 20,000 American and Allied servicemen and the Cabanatuan raid. civilians were held there from 1942 to 1945. Photo: The National Archives A marble altar rests atop a 90-foot square concrete base vessels sailing to Japan. Unmarked, many of these ships were sunk in the center of the area. by US aircraft and submarines. Flanking the entrance are About 500 POWs remained in Cabanatuan. -

Hall's Manila Bibliography

05 July 2015 THE RODERICK HALL COLLECTION OF BOOKS ON MANILA AND THE PHILIPPINES DURING WORLD WAR II IN MEMORY OF ANGELINA RICO de McMICKING, CONSUELO McMICKING HALL, LT. ALFRED L. McMICKING AND HELEN McMICKING, EXECUTED IN MANILA, JANUARY 1945 The focus of this collection is personal experiences, both civilian and military, within the Philippines during the Japanese occupation. ABAÑO, O.P., Rev. Fr. Isidro : Executive Editor Title: FEBRUARY 3, 1945: UST IN RETROSPECT A booklet commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Liberation of the University of Santo Tomas. ABAYA, Hernando J : Author Title: BETRAYAL IN THE PHILIPPINES Published by: A.A. Wyn, Inc. New York 1946 Mr. Abaya lived through the Japanese occupation and participated in many of the underground struggles he describes. A former confidential secretary in the office of the late President Quezon, he worked as a reporter and editor for numerous magazines and newspapers in the Philippines. Here he carefully documents collaborationist charges against President Roxas and others who joined the Japanese puppet government. ABELLANA, Jovito : Author Title: MY MOMENTS OF WAR TO REMEMBER BY Published by: University of San Carlos Press, Cebu, 2011 ISBN #: 978-971-539-019-4 Personal memoir of the Governor of Cebu during WWII, written during and just after the war but not published until 2011; a candid story about the treatment of prisoners in Cebu by the Kempei Tai. Many were arrested as a result of collaborators who are named but escaped punishment in the post war amnesty. ABRAHAM, Abie : Author Title: GHOST OF BATAAN SPEAKS Published by: Beaver Pond Publishing, PA 16125, 1971 This is a first-hand account of the disastrous events that took place from December 7, 1941 until the author returned to the US in 1947. -

Please Help Get the Congressional Gold Medal for the World War Ii Rangers

CAMPAIGNS* INVASIONS* BATTLES* RAIDS* Algiers-Tunisian North Africa Venafro-San Pietro Dieppe Sicily-Naples Sicily Landings Cisterna Sened Station Foggia-Rome Salerno Beachhead Pointe duHoc Cabanatuan Arno-Normandy Anzio Beachhead Vermilliers-Brest Aparri Northern France Normandy Beachhead LeConquet Peninsula Carbruan Hills INVASIONRhineland-Central Philippine Landings Huertgen Forest Homobon Europe-Ardennes Arzew-Oran Castle Hill ‘400’ Alsace El Guettar DESCENDANTS OF WWII RANGERS Saar, Roer & Rhine Rivers New Guinea Gela-Licata Battle of the Bulge Luzon Pursuit to Messina Leyte Landings Chiunzi Pass PLEASE HELP GET THE CONGRESSIONAL GOLD MEDAL FOR THE WORLD WAR II RANGERS TIME IS SHORT THEY NEED YOUR HELP WHAT YOU CAN DO: Contact Your United States Senators and Ask Them to Co-Sponsor Senate Bill S.1872 and Also Contact Your United States Representatives and Ask Them to Co-Sponsor U.S. House Bill H.R. 3577 Please keep us informed of any success. Our Contact Person: J. Ronald Hudnell Cell 336-577-9937 [email protected] www.wwiirangers.org Information Attached ( Scroll Down): WW II Rangers by State as of July 9, 2021 Fact Sheet on U.S. Army Rangers Who Fought in World War II Endorsements for the WW II Ranger Congressional Gold Medal WWII Rangers by State as of 07-09-21 Still Overseas Still Overseas Remain KIA Cemeteries Remain KIA Cemeteries AK 3 1 1 MT 10 AL 34 5 1 NC 50 5 2 AR 38 3 ND 14 3 1 AZ 21 1 NE 27 3 3 CA 146 3 21 11 NH 10 2 2 CO 26 4 NJ 115 23 17 CT 55 1 9 6 NM 11 1 1 DC 8 NV 8 DE 6 2 NY 230 38 24 FL 100 2 2 2 OH 170 30 11 -

Ta Document Collection of The

The Filipino American Experience Research Project Copyright © October 5, 1998 D – R – A – F – T A DOCUMENT COLLECTION OF THE HISTORY OF THE 1ST FILIPINO INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II A Field Study submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University in partial fullfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Ethnic Studies by Alex Sandoval Fabros, Jr. San Francisco, California August, 1997 D – R – A – F – T Page 1 The Filipino American Experience Research Project Copyright © October 5, 1998 D – R – A – F – T Copyright by Alex Sandoval Fabros, Jr. 1997 D – R – A – F – T Page 2 The Filipino American Experience Research Project Copyright © October 5, 1998 D – R – A – F – T CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read A DOCUMENT COLLECTION OF THE HISTORY OF THE 1ST FILIPINO INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II by Alex Sandoval Fabros, Jr., and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fullfillment of the requiremnts for the degree: Master of Arts in Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University. __________________________________________________ Danilo T. Begonia Professor of Ethnic Studies __________________________________________________ Marlon K. Hom Professor of Ethnic Studies D – R – A – F – T Page 3 The Filipino American Experience Research Project Copyright © October 5, 1998 D – R – A – F – T Preface Among the annals of American military histories, the First Filipino Infantry Regiment, Army of the United States, is considered to be unique. A military unit is created out of a need for a purpose, each with a mission to fulfill. -

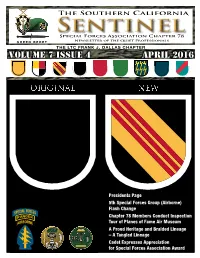

Volume 7 Issue 4 April 2016

volume 7 issue 4 April 2016 Presidents Page 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne) Flash Change Chapter 78 Members Conduct Inspection Tour of Planes of Fame Air Museum A Proud Heritage and Braided Lineage – A Tangled Lineage Cadet Expresses Appreciation for Special Forces Association Award Please visit us at www.specialforces78.com and www.sfa78cup.com EDITOR’S COMMENTS 5th Special Forces Group Returns In this Issue: to Vietnam Era Flash Presidents Page .............................................................. 1 Wednesday, March 23 marks a historically 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne) Flash Change ...... 2 significant date for all Green Berets with the Images from the 5th Special Forces Group 5th Special Forces Group’s return to the beret Flash Change Ceremony ................................................ 3 Lonny Holmes flash of the Vietnam era. This ceremony was Chapter 78 Members Conduct Inspection of Sentinel Editor held at Gabriel Field*, 5th SFG(A) Headquar- Tour of Planes of Fame Air Museum .............................. 5 ters, Fort Campbell, Kentucky and was led by Images from Chapter 78 at Planes Group Commander, COL Kevin Leahy and at- of Fame Air Museum ...................................................... 6 tended by Chief of Staff of the Army GEN Mark Milley, MG Jack A Proud Heritage and Braided Lineage Singlaub and many 5th SFGA Vietnam era Green Berets. Brad – A Tangled Lineage ....................................................... 8 Welker and John “Tilt” Meyer represented Chapter 78 and took Cadet Expresses Appreciation several nice photographs. for Special Forces Association Award ........................ 10 MAJ John Padgett (retired) pens a story in this issue of the Sentinel COVER: 5th Special Forces Group officially changed the unit’s beret on the “Flash Change Ceremony” and presents a historical back- flash back to the one utilized by 5th Group during the Vietnam War. -

Breakneck Ridge ••••••••••••••••••••• 12 the Third Day on Breakneck Ridge •••••••••••••••••••••• 13

tI··'J~ .. /.,."".;.,.,., ~. .' . ! Staft Department THE INFANTRY SCHOOL - - .' ~ Fort Benning, Georgia .. ADVANCED INFANTRY OFFICERS COURSE , 1949-1950 . THE OPERATION:J OF' COMPANY L, 21ST ,INFANTRY <. '. ,(24TliINFANTRY DIVISION) SOUTH OF PINAMOPOAN, '. .+BREAKNECKRIDGE) ,·LaY-'l.'E ISLAND,· P,. I., ~5-15NOVEMBER 1944 .. ' .. .... '(~EYTECAMPA'IGN)' .. ( Pers onal Exper:!;enc-e of a CompanY' CODm1ander)' ' of Operationdeser1bed: INFAN'l'R! RIFLE 'COMPANY.~.['.lOKING •. AS PART OFANINFAN';l'RY REGIMENT IN A MEETING ENGAGEdN«" .. '. Oaptain. Kerm1tB. Blane1~ Infantry. '. ADVANCl!'DINFANTRYOFF10mRS C~SSNO.2 ..... l~:··· • TABLE OF CONTENTS INDEX. ••••••••••••••• 0 • •••• ,. ....... , • • .. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 BIBLIOGRAP'HY •••••••••••••••••••• ., • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 2: ORIENTATION ....................... 'III • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 4 Introduction.......................................... 4 The General Situation................................. 5 Geography, Weather and Terrain........................ 6 • The General Dispositions of the Enemy Units on Leyte.. 7 General Disposition and Plans of X Corps.............. 8 NARRATION •••••••••••••••••••• ., .......................... ~ • • • • • 10 The First Ocoupation of the Ridge ••••••••••••••••••••• 10 The Second Day on Breakneck Ridge ••••••••••••••••••••• 12 The Third Day on Breakneck Ridge •••••••••••••••••••••• 13 The Fourth Day on Breakneok Ridge....... ••• • •••• •.••••• 13 The Fifth Day on Breakneck -

The Palawan Massacre

CATALYST FOR ACTION The Palawan Massacre Michael E. Krivdo 35 | VOL 14 NO 1 fter three years of brutal captivity under the Despite these precautions, word spread quickly as evidence Japanese, the 150 American inmates of prisoner of of the incident and others just as grisly. Leaders decided to A war (POW) Camp 10-A on the western Philippine act and to rescue prisoners, detainees, and internees from island of Palawan had developed an instinct for similar fates. recognizing the abnormal. For several months in late 1944 On that fateful morning of 14 December the guards the Palawan POWs had worked hard to build a runway for roused the prisoners at 0200 hours, far earlier than normal. the Japanese Army. Lately, their duties included repairing At the airfield before work the POWs saw more guards damage caused by almost daily U.S. bombing attacks.1 than usual. Many chalked it up to pre-invasion jitters As 1944 came to an end, many of the prisoners noticed because the Allies had been bombing Japanese bases in changes in the demeanor of their guards. The Japanese preparation of an invasion. The laborers were ordered had become increasingly short-tempered and imposed to repair damage and improve the airstrip. As he was cruel punishments for the slightest of infractions. On the working to fill a bomb crater, Marine Corporal (CPL) Rufus morning of 14 December 1944, the POWs’ sense of dread W. Smith turned to his long-time friend, CPL Glenn W. reached new heights.2 McDole, and said, “Something is going on, Dole.