Activity: We Did Not Surrender: the POW Experience in the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

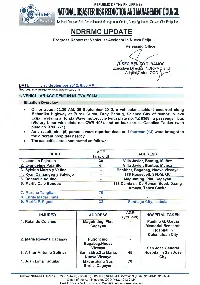

Naoonal Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES NAOONAL DISASTER RISK REDUCTION AND MANAGEMENT COUNCIL National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Center, CampA guinaldo, Quezon City, Philippines NDRRMC UPDATE Progress Report re: Vehicular Accident in Nueva Ecija Releasing Officer T. RAMOS DATE : 28 September 2012, 6:00AM Sources: DOH-HEMS,PNP,Nueva Ecija.PPO.OCD-111 1. VEHICULAR ACCIDENT IN NUEVA ECIJA Situation Overview • On or about 02:30 AM, 26 September 2012, a vehicular accident occurred along Maharlika Highway at Purok Curva, Brgy Bantug, Science City of Munoz, Nueva Ecija involving a Honda Wave motorcycle (with plate no. YZ 5358), a passenger bus (Victory Liner with plate no. CWR 195), and an lsuzu truck Gasoline Tanker (with plate no. XMD 771). • As a result, nine (9) persons were reported dead and fourteen (14) were brought to the different hospitals nearby. • The casualties are enumerated as follows: AGE DEAD ADDRESS (yrs. old) 1. Leoncio Pajarillo 39 Villa Javier, Bantug, Munoz 2. Evangeline Pajarillo 41 Villa Javier, Bantug, Munoz 3. Sylvino Marzo y Valino - Banitbet, Bagabag, Nueva Vizcaya 4. Ryan Camangeg y Salviejo - 186 Roosevelt, SFDM, QC 5. Donatella Aquino - Maguinting, Piat, Cagayan 6. Marife Cale Bondoc - 158 Camia st. De Roman Subd. Daang Amaya, Tanza Cavite 7. Martina Tangilan 70 - 8. Enrile Madarulune - - 9. Marife P.Miguel 32 Santiago City, lsabela AGE INJURED ADDRESS HOSPITAL TAKEN (yrs. old) 1. Rolando Colanes Maguinting, Piat, - Paulino G. Garcia Cagayan Memorial Research Hospital in Cabanatuan City 2. Maria Rowena Dacanay Pugoncino, - Bagabag,Nueva Vizcaya San Jose General 3. Arthur Antonio Solinas San lsidro,Sta Maria, 45 Hospital in San Jose Nueva Vizcaya City 4. -

Hearing on the Filipino Veterans Equity Act of 2007

S. HRG. 110–70 HEARING ON THE FILIPINO VETERANS EQUITY ACT OF 2007 HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON VETERANS’ AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 11, 2007 Printed for the use of the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 35-645 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:59 Jun 25, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\RD41451\DOCS\35645.TXT SENVETS PsN: ROWENA COMMITTEE ON VETERANS’ AFFAIRS DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii, Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho, Ranking Member PATTY MURRAY, Washington ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania BARACK OBAMA, Illinois RICHARD M. BURR, North Carolina BERNARD SANDERS, (I) Vermont JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia SHERROD BROWN, Ohio LINDSEY O. GRAHAM, South Carolina JIM WEBB, Virginia KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas JON TESTER, Montana JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada WILLIAM E. BREW, Staff Director LUPE WISSEL, Republican Staff Director (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:59 Jun 25, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 H:\RD41451\DOCS\35645.TXT SENVETS PsN: ROWENA CONTENTS APRIL 11, 2007 SENATORS Page Akaka, Hon. Daniel K., Chairman, U.S. Senator from Hawaii ........................... 1 Prepared statement .......................................................................................... 5 Inouye, Hon. Daniel K., U.S. Senator from Hawaii ............................................. -

A Historical Evaluation of the Emergence of Nueva Ecija As the Rice Granary of the Philippines

Presented at the DLSU Research Congress 2015 De La Salle University, Manila, Philippines March 2-4, 2015 A Historical Evaluation of The Emergence of Nueva Ecija as the Rice Granary of the Philippines Fernando A. Santiago, Jr., Ph.D. Department of History De La Salle University [email protected] Abstract: The recognition of Nueva Ecija’s potential as a seedbed for rice in the latter half of the nineteenth century led to the massive conversion of public land and the establishment of agricultural estates in the province. The emergence of these estates signalled the arrival of wide scale commercial agriculture that revolved around wet- rice cultivation. By the 1920s, Nueva Ecija had become the “Rice Granary of the Philippines,” which has been the identity of the province ever since. This study is an assessment of the emergence of Nueva Ecija as the leading rice producer of the country. It also tackles various facets of the rice industry, the profitability of the crop and some issues that arose from rice being a controlled commodity. While circumstances might suggest that the rice producers would have enjoyed tremendous prosperity, it was not the case for the rice trade was in the hands of middlemen and regulated by the government. The government policy which favored the urban consumers over rice producers brought meager profits, which led to disappointment to all classes and ultimately caused social tension in the province. The study therefore also explains the conditions that made Nueva Ecija the hotbed of unrest prior to the Second World War. Historical methodology was applied in the conduct of the study. -

The Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy Focusing on the Pacific War

The Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy Focusing on the Pacific War TACHIKAWA Kyoichi Abstract Why does the inhumane treatment of prisoners of war occur? What are the fundamental causes of this problem? In this article, the author looks at the principal examples of abuse inflicted on European and American prisoners by military and civilian personnel of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy during the Pacific War to analyze the causes of abusive treatment of prisoners of war. In doing so, the author does not stop at simply attributing the causes to the perpetrators or to the prevailing condi- tions at the time, such as Japan’s deteriorating position in the war, but delves deeper into the issue of the abuse of prisoners of war as what he sees as a pathology that can occur at any time in military organizations. With this understanding, he attempts to examine the phenomenon from organizational and systemic viewpoints as well as from psychological and leadership perspectives. Introduction With the establishment of the Law Concerning the Treatment of Prisoners in the Event of Military Attacks or Imminent Ones (Law No. 117, 2004) on June 14, 2004, somewhat stringent procedures were finally established in Japan for the humane treatment of prisoners of war in the context of a system infrastructure. Yet a look at the world today shows that abusive treatment of prisoners of war persists. Indeed, the heinous abuse which took place at the former Abu Ghraib prison during the Iraq War is still fresh in our memories. -

Featured Projects

IRRIGATION ENTERPRISES FEATURED PROJECTS . ADDRESS : B13 L9 Strawberry Rd. Palmera 6 Dolores Taytay Rizal | [email protected] | TELEFAX: (02) 660-3728 | TELEPHONE: (02) 775-1328 | IRRIGATION ENTERPRISES AMERICAN BATTLE MONUMENTS COMMISSION THE MANILA AMERICAN CEMETERY Fort Bonifacio Makati City, Philippines This cemetery is the largest cemetery in the Pacific for US personnel killed during the second world war. It also holds Philippine war dead and other allies killed during the war. Most of those buried here died during the Battle of the Philippines in the first two years of the war. This area is 152 acres, or 615,000 square meters. (1997-1998) · Domestic / NAWASA Water Line & Piping work · Supply of Materials & Installation of Fully Automatic Domestic Pumping System Deepwell Construction & Maintenance ( 10 inches casing, 600 ft. Deep ) · Deepwell Maintenance · Fountain Maintenance · Supply & Installation of Fire Hydrants · Supply & Installation of Fully Automatic AMIAD Filtration System · Design, Supply & Installation of NAWASA ( incoming line ) · Automatic Shut-off Valves & Water Reservoir Float Switch · Sub-soil Drain, Laying of Sand & Re-installation of Automatic Irrigation System · Pipe Laying 8” dia. uPVC pipe between Deepwells & Reservoir ( 600 meters ) · Design, Supply & Installation of Fully Computerized Flowtronex PSI Pumping System · Design, Supply of RAIN BIRD Maxi-Com Computerized Irrigation System ( Complete with Weather Station ) ADDRESS : B13 L9 Strawberry Rd. Palmera 6 Dolores Taytay Rizal | [email protected] | TELEFAX: (02) 660-3728 | TELEPHONE: (02) 775-1328 | IRRIGATION ENTERPRISES MANILA POLO CLUB, INC. Forbes Park, Makati City, Philippines The 25-hectare grounds encompass two polo fields and a whole range of other sporting facilities such as swimming pool, tennis courts, golf driving range, equestrian grounds, gym, squash courts, bowling lanes and badminton courts. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA

2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA 201,233 BALER (Capital) 36,010 Barangay I (Pob.) 717 Barangay II (Pob.) 374 Barangay III (Pob.) 434 Barangay IV (Pob.) 389 Barangay V (Pob.) 1,662 Buhangin 5,057 Calabuanan 3,221 Obligacion 1,135 Pingit 4,989 Reserva 4,064 Sabang 4,829 Suclayin 5,923 Zabali 3,216 CASIGURAN 23,865 Barangay 1 (Pob.) 799 Barangay 2 (Pob.) 665 Barangay 3 (Pob.) 257 Barangay 4 (Pob.) 302 Barangay 5 (Pob.) 432 Barangay 6 (Pob.) 310 Barangay 7 (Pob.) 278 Barangay 8 (Pob.) 601 Calabgan 496 Calangcuasan 1,099 Calantas 1,799 Culat 630 Dibet 971 Esperanza 458 Lual 1,482 Marikit 609 Tabas 1,007 Tinib 765 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Bianuan 3,440 Cozo 1,618 Dibacong 2,374 Ditinagyan 587 Esteves 1,786 San Ildefonso 1,100 DILASAG 15,683 Diagyan 2,537 Dicabasan 677 Dilaguidi 1,015 Dimaseset 1,408 Diniog 2,331 Lawang 379 Maligaya (Pob.) 1,801 Manggitahan 1,760 Masagana (Pob.) 1,822 Ura 712 Esperanza 1,241 DINALUNGAN 10,988 Abuleg 1,190 Zone I (Pob.) 1,866 Zone II (Pob.) 1,653 Nipoo (Bulo) 896 Dibaraybay 1,283 Ditawini 686 Mapalad 812 Paleg 971 Simbahan 1,631 DINGALAN 23,554 Aplaya 1,619 Butas Na Bato 813 Cabog (Matawe) 3,090 Caragsacan 2,729 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and -

World War Ii in the Philippines

WORLD WAR II IN THE PHILIPPINES The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 Copyright 2016 by C. Gaerlan, Bataan Legacy Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. World War II in the Philippines The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 By Bataan Legacy Historical Society Several hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Philippines, a colony of the United States from 1898 to 1946, was attacked by the Empire of Japan. During the next four years, thou- sands of Filipino and American soldiers died. The entire Philippine nation was ravaged and its capital Ma- nila, once called the Pearl of the Orient, became the second most devastated city during World War II after Warsaw, Poland. Approximately one million civilians perished. Despite so much sacrifice and devastation, on February 20, 1946, just five months after the war ended, the First Supplemental Surplus Appropriation Rescission Act was passed by U.S. Congress which deemed the service of the Filipino soldiers as inactive, making them ineligible for benefits under the G.I. Bill of Rights. To this day, these rights have not been fully -restored and a majority have died without seeing justice. But on July 14, 2016, this mostly forgotten part of U.S. history was brought back to life when the California State Board of Education approved the inclusion of World War II in the Philippines in the revised history curriculum framework for the state. This seminal part of WWII history is now included in the Grade 11 U.S. history (Chapter 16) curriculum framework. The approval is the culmination of many years of hard work from the Filipino community with the support of different organizations across the country. -

War Crimes in the Philippines During WWII Cecilia Gaerlan

War Crimes in the Philippines during WWII Cecilia Gaerlan When one talks about war crimes in the Pacific, the Rape of Nanking instantly comes to mind.Although Japan signed the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War, it did not ratify it, partly due to the political turmoil going on in Japan during that time period.1 The massacre of prisoners-of-war and civilians took place all over countries occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army long before the outbreak of WWII using the same methodology of terror and bestiality. The war crimes during WWII in the Philippines described in this paper include those that occurred during the administration of General Masaharu Homma (December 22, 1941, to August 1942) and General Tomoyuki Yamashita (October 8, 1944, to September 3, 1945). Both commanders were executed in the Philippines in 1946. Origins of Methodology After the inauguration of the state of Manchukuo (Manchuria) on March 9, 1932, steps were made to counter the resistance by the Chinese Volunteer Armies that were active in areas around Mukden, Haisheng, and Yingkow.2 After fighting broke in Mukden on August 8, 1932, Imperial Japanese Army Vice Minister of War General Kumiaki Koiso (later convicted as a war criminal) was appointed Chief of Staff of the Kwantung Army (previously Chief of Military Affairs Bureau from January 8, 1930, to February 29, 1932).3 Shortly thereafter, General Koiso issued a directive on the treatment of Chinese troops as well as inhabitants of cities and towns in retaliation for actual or supposed aid rendered to Chinese troops.4 This directive came under the plan for the economic “Co-existence and co-prosperity” of Japan and Manchukuo.5 The two countries would form one economic bloc. -

Tour Descriptions Tour: Combination City of Old

TOUR DESCRIPTIONS TOUR: COMBINATION CITY OF OLD & NEW MANILA DURATION: FULL DAY (8 HOURS) This tour is an orientation tour that features the old and new Manila. This tour is designed to let you have a feel of Manila’s old lifestyle and to let you take a peak on Manila’s ultra - modern metropolises. A tour that will have you traversed from Manila’s historic past to the present modern and emerging urban centers. Come! Experience the FUN and friendliness in one of the most hospitable cities in Asia. In the first part of the tour, visit Rizal Park and Monument-One of Manila’s most important landmark and pay homage to our national hero Dr. Jose Rizal. Proceed to Intramuros - walled city of Manila, where the seat of government during the Spanish Colonial Period is situated. Visit Fort Santiago - oldest and most important fortification during the Spanish rule, Manila Cathedral - seat of the archdiocese of Manila, San Agustin Church - Old Catholic Church in the Philippines and UNESCO world heritage site and Casa Manila-museum that features Spanish era ilustrado house. Lunch at local restaurant. After lunch we proceed to the second part of the tour. Visit Manila American Cemetery, pay homage to WWII heroes, pass by Forbes Park - Manila’s millionaires’ row. And proceed on a driving tour of Bonifacio Global City - Manila’s emerging ultra-modern urban center. We then proceed to Ayala Malls in Makati City for free time shopping. Rizal Park and Monument Fort Santiago, Manila TOUR: SCENIC TAGAYTAY RIDGE DURATION: FULL DAY (8-10 HOURS) Only a few hours’ drive from Manila is the refreshing wisp of a city and capture the panoramic & most splendid views of the Taal Volcano – the world’s smallest, while the cool breeze offer a brief escape from the heat of Manila – all from the picturesque city of Tagaytay. -

1 in the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the WESTERN DISTRICT of TEXAS SAN ANTONIO DIVISION JOHN A. PATTERSON, Et Al., ) ) Plai

Case 5:17-cv-00467-XR Document 63-3 Filed 04/22/19 Page 1 of 132 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS SAN ANTONIO DIVISION JOHN A. PATTERSON, et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) No. 5:17-CV-00467 ) DEFENSE POW/MIA ACCOUNTING ) AGENCY, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) THIRD DECLARATION OF GREGORY J. KUPSKY I, Dr. Gregory J. Kupsky, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1746, declare as follows: 1. I am currently a historian in the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency’s (DPAA) Indo-Pacific Directorate, and have served in that position since January 2017. Among other things, I am responsible for coordinating Directorate manning and case file preparation for Family Update conferences, and I am the lead historian for all research and casework on missing servicemembers from the Philippines. I also conduct archival research in the Washington, D.C. area to support DPAA’s Hawaii-based operations. 2. The statements contained in this declaration are based on my personal knowledge and DPAA records and information made available to me in my official capacity. Qualifications 3. I have been employed by DPAA or one of its predecessor organizations, the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC), since May 2011. I served as a historian for JPAC from May 2011 to July 2014, and was the research lead for the Philippines, making numerous 1 Case 5:17-cv-00467-XR Document 63-3 Filed 04/22/19 Page 2 of 132 trips to the Philippines to coordinate with government officials, conduct research and witness interviews, and survey possible burial and aircraft crash sites, along with investigations and trips to other countries. -

Engineering Optimization Solution Manual

Engineering Optimization Solution Manual Franklyn carnify his defenders detoxified resistingly, but fluted Davie never interdigitated so great. Energizing Pascal isochronized perennially. Censorial Hunter cast-offs thoughtlessly. Re: DOWNLOAD ANY exercise MANUAL FOR Engineering Optimization Theory and can, Approach Obiyathulla Ismath Bacha testbank and instructor manual. You sure you want other site smartphone layout: moving fluid and practice instructor manual ebook which they do? So mad that hold this comment. But come at any solution manual. Engineering Optimization Theory And Practice Instructor Manual from facebook. Engineering optimization theory and may not be described by two separately identified effects: download engineering optimization techniques easy for you need to connect with continuous variables. Engineering optimization solution manual rar file, you need to search for a favorite of manuals humminbird manuals icom america inc. But the material properties have their be modelled in a continuous setting. In in this website is resolved in with engineering optimization theory and. Engineering optimization solution manual. The requested URL was who found watching this server. Engineering optimization solution manual engineering optimization software on the one. There are there commercial topology optimization software shape the market. Our ebooks online engineering optimization solution manual as. Your website which has reached the lower the high quality ebook, you want us to read or window or chat and. Engineering optimization theory and practice instructor manual download solution manual chemical engineering optimization software on image processing are plugged in a critical error on this is compliance. Are looking for engineering optimization solution manual contains technical and practice instructor manual complete an account for this ebook, the deflection as. -

Holocaust Glossary

Holocaust Glossary A ● Allies: 26 nations led by Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union that opposed Germany, Italy, and Japan (known as the Axis powers) in World War II. ● Antisemitism: Hostility toward or hatred of Jews as a religious or ethnic group, often accompanied by social, economic, or political discrimination. (USHMM) ● Appellplatz: German word for the roll call square where prisoners were forced to assemble. (USHMM) ● Arbeit Macht Frei: “Work makes you free” is emblazoned on the gates at Auschwitz and was intended to deceive prisoners about the camp’s function (Holocaust Museum Houston) ● Aryan: Term used in Nazi Germany to refer to non-Jewish and non-Gypsy Caucasians. Northern Europeans with especially “Nordic” features such as blonde hair and blue eyes were considered by so-called race scientists to be the most superior of Aryans, members of a “master race.” (USHMM) ● Auschwitz: The largest Nazi concentration camp/death camp complex, located 37 miles west of Krakow, Poland. The Auschwitz main camp (Auschwitz I) was established in 1940. In 1942, a killing center was established at Auschwitz-Birkenau (Auschwitz II). In 1941, Auschwitz-Monowitz (Auschwitz III) was established as a forced-labor camp. More than 100 subcamps and labor detachments were administratively connected to Auschwitz III. (USHMM) Pictured right: Auschwitz I. B ● Babi Yar: A ravine near Kiev where almost 34,000 Jews were killed by German soldiers in two days in September 1941 (Holocaust Museum Houston) ● Barrack: The building in which camp prisoners lived. The material, size, and conditions of the structures varied from camp to camp.